In his book Green Urbanism Tim Beatley touted Portland, Oregon as one example of progressive regional, bioregional, and metropolitan-scale greenspace planning in the U.S. It is true that the Portland metropolitan region is well known for its land use planning and sustainable practices. Portland itself has more LEED buildings than any other American city. While the nation had increased greenhouse gases by 13% between 1990 and 2001, Portland’s fell by 12%. During this period transit use increased 75% and bicycle commuting 500%. Between 1990 and 2000 the Portland region’s population grew by 31% but consumed only 4% more land to accommodate that growth. By contrast the Chicago region grew by 4% yet consumed 36% more land (Chicago Wilderness 1999: 21).

However, until relatively recently our region’s urban nature agenda has lagged behind in both local and regional land use planning. Competing policies have often made otherwise progressive land use planning objectives and natural resource protection a zero sum proposition. Urban planners have focused almost exclusively on creating compact urban form and containing sprawl to protect farm land outside the region’s Urban Growth Boundary (UGB). They have maintained that protecting “too much” urban greenspace inside the UGB would result in loss of the buildable lands inventory inside the region’s UGB. Most politicians, especially in Portland and Metro, ran their campaigns on a promise to hold a tight UGB.

Unfortunately, the UGB became a sacrosanct icon, an end to a means rather than merely a planning tool. As a result the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan region has failed to adequately protect natural resources within the region’s Urban Growth Boundary and inside the region’s twenty-five individual cities, including Portland (Houck and Labbe 2006, p. 40).

Lessons learned: size and scale matter

One of many barriers to protecting urban natural areas is knowing where they are and their relative importance to maintaining biodiversity.

“Connectivity is needed both within a particular network and across many networks of human, built, and natural systems in a region. Some structures and patterns would be more appropriately understood at a regional and metropolitan scale; others, at the city or neighborhood scale; and still others at the site scale.” (Gerling and Kellett, 2006).

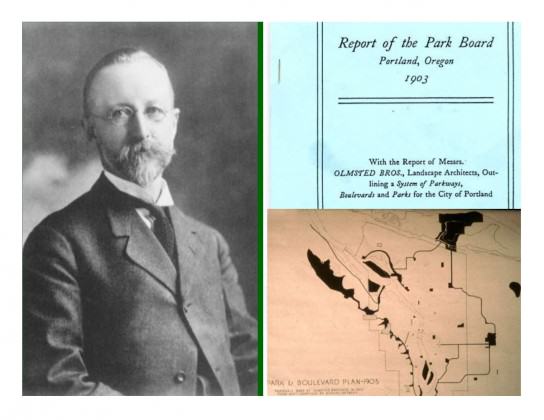

To be fair, the UGB has been very successful at maintaining the region’s compact urban form and there have been some significant milestones in our region concerning description and protection of special urban landscapes. The earliest is John Charles Olmsted’s 1903 master plan for Portland’s park system in which he observed that the city was “most fortunate, in comparison with the majority of American cities, in possessing such varied and wonderfully strong and interesting landscape features” (Olmsted, 1903: 34).

Olmsted proposed that Portland create a ”system of public squares, neighborhood parks, playgrounds, scenic reservations, rural or suburban parks, and boulevards and parkways” built around features that are today among Portland’s most treasured natural landscapes (Olmsted,1903: 36-68). Unlike Seattle and Spokane, two cities he also visited on his train excursion to the Pacific Northwest, Portland was too tight with its budget to pay Olmsted to create a map. It fell to later park advocates to produce such a map. And, while his vision included significant natural areas, it was solely for the city of Portland, not the metropolitan region.

Needless to say, it was neither GIS-based nor scientifically derived. Still, many of his recommendations ring true today. For example, he addressed urban stream management in a prescient manner, especially with regard to today’s concerns with stormwater management and adaptation to climate change, when he wrote:

“Marked economy in municipal development may also be effected by laying out parkways and park, while land is cheap, so as to embrace streams that carry at times more water than can be taken care of by drain pipes of ordinary size. Thus brooks or little rivers which would otherwise become nuisances that would some day have to be put in large underground conduits at enormous expense, may be made the occasion for delightful local pleasure grounds or attractive parkways.” (Olmsted 1903)

Similarly, in yet another forward thinking passage, he admonished the city to avoid building on steep slopes:

The broken hillsides between Portland Heights, and the comparatively flat portion of the city below, are neither economical nor desirable as building sites for crowded residences; It would be a very profitable investment for the city to take these lands out of the market and use them for pleasure grounds for the benefit of the citizens at large, and for the particular benefit of adjoining properties below.” (Olmsted 1903)

There were, however, no turn-of-the-century maps to represent hazard avoidance, much less biodiversity hot spots.

“Another school of thought…believes that open-space planning should take its cue from the patterns of nature itself—the water table, the flood plains, the ridges, the woods, and above all, the streams…I think these people are right and that there is strong evidence to prove that their way works…” (William H Whyte, 1968)

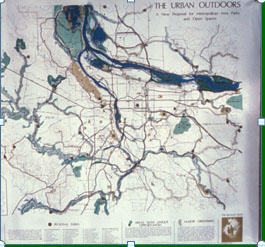

Landscape planning did not truly get underway in our region until 1971 when the Columbia Region Association of Governments (CRAG) laid out a bi-state Park and Open Space System based on the premise that “open spaces are needed for immediate enjoyment and use within the urban complex.” (CRAG,1971: 3-4).

The CRAG report did include a map, but it merely conceptualized some of the region’s most significant natural areas in broad strokes. It contained no information regarding the region’s flora and fauna. It also went to the region’s bookshelves because it lacked the political and public support necessary for its implementation. The bounty of natural resources outside the urbanized portion of our region (Columbia River Gorge, Mt Hood Wilderness, Oregon Coast, and Willamette Valley) drew the region’s attention to conservation, resulting in a lack of protection within the urban core.

Scale and science: getting it right

It was another twenty years before public alarm at the loss of local greenspaces grew into a full-throated grassroots, citizen-led demand for protection of urban nature at both the local and regional scales.

The Audubon Society of Portland, 40-Mile Loop Land Trust, Metro (the only directly elected regional government in the U.S.), and Portland State University initiated a bi-state inventory of natural areas in 1989. Under the direction of Portland State University Geography Department’s Dr. Joe Poracsky, color infrared photography of the four county region was used to create a map that for the first time depicted the remaining natural areas.

Three years later Metro adopted the Metropolitan Greenspaces Master Plan calling for “a cooperative regional system of natural areas, open space, trails, and greenways for wildlife and people” in the four-county metropolitan area that would “protect and manage significant natural areas through a partnership with governments, nonprofit organizations, land trusts, businesses and citizens.” The system’s primary purpose was to preserve the diversity of plant and animal life in the urban environment using watersheds as the basis for ecological planning and restore green and open spaces in neighborhoods where natural areas had all but eliminated (Metro, 1992).

Three years later Metro adopted the Metropolitan Greenspaces Master Plan calling for “a cooperative regional system of natural areas, open space, trails, and greenways for wildlife and people” in the four-county metropolitan area that would “protect and manage significant natural areas through a partnership with governments, nonprofit organizations, land trusts, businesses and citizens.” The system’s primary purpose was to preserve the diversity of plant and animal life in the urban environment using watersheds as the basis for ecological planning and restore green and open spaces in neighborhoods where natural areas had all but eliminated (Metro, 1992).

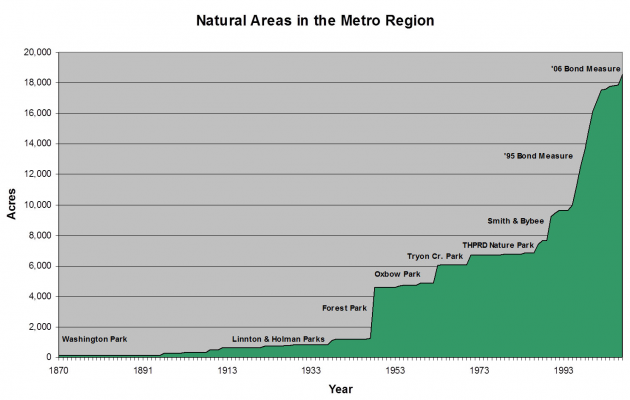

In 1995 a coalition of park advocates and Metro threw their political weight behind the passage of a region-wide bond, which produced $135.6 million for urban natural area acquisition. In the fall of 2006 Metro passed a second bond that will provide another $227.4 million for additional acquisitions. The combined $363 million has allowed Metro to purchase over 12,000 acres of biologically rich natural areas and parkland, bringing the total holding to over 16,000 acres. Local park providers across the Columbia River in Clark County, Washington added thousands more acres with their local share and Washington’s Legacy Lands program.

Regional restoration strategy and biodiversity guide for the greater Portland-Vancouver region

We envision an exceptional, interconnected system of neighborhood, community, and regional parks, natural areas,trails, open spaces, and recreation opportunities distributed equitably throughout the region. This region-wide system is an essential element of the greater Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area’s economic success, ecological health, civic vitality, and overall quality of life. — The Intertwine Vision

In the summer of 2007 the Metro Council President, David Bragdon invited Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and several other dignitaries from around the U.S. and issued a challenge. Bragdon declared that his top priority in his final two years in office was to create the “greatest park system in the world” in the Portland-Vancouver region. Subsequent to his departure to work for New York City as director of their planning and sustainability program The Intertwine Alliance, a new nonprofit organization was created to embark on creation of that system, now known as The Intertwine.

The Intertwine vision called for the creation of a regional biodiversity plan, mirroring plans created by Chicago Wilderness and Houston Wilderness, two of our national partners in the Metropolitan Greenspaces Alliance.

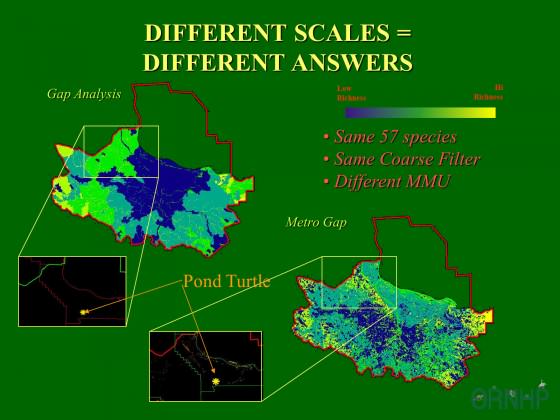

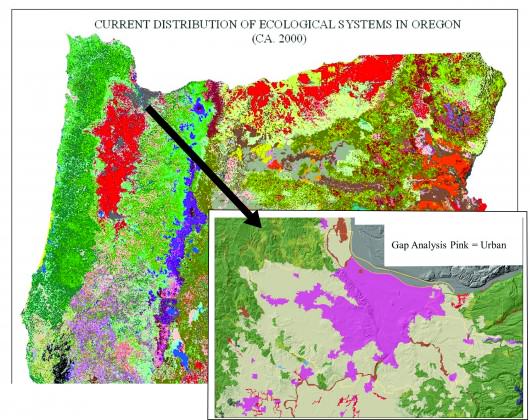

There had been earlier efforts to map regionally and locally significant landscapes that would contribute to maintaining biodiversity in our region but they all had drawbacks, mostly related to scale and geographic extent. The 1989 PSU and Metro effort suffered from the fact that the minimum mapping unit for upland forests was five-acres. The habitat map did not cover the entire 3,000 square mile Intertwine geography. An earlier effort by The Nature Conservancy’s Oregon Natural Heritage Database project, which mapped Oregon, Washington and Idaho, had pixels so large that the entire Portland metropolitan region was characterized as “urban” — that is, their mapping suggested that the entire metropolitan region was a biodiversity free zone.

Once again both scale and geographic extent were all wrong.

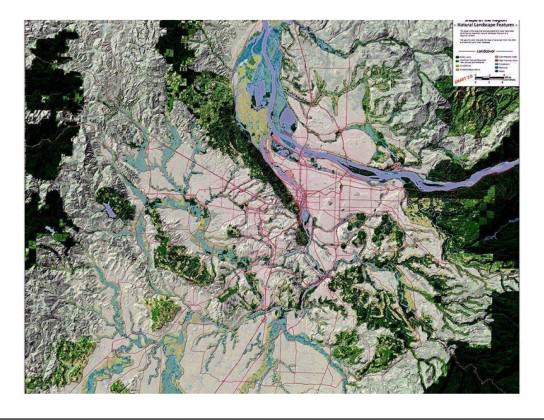

In 2005 the region’s Greenspaces Policy Advisory Committee convened a diverse expert panel that created a map (below) which depicted what in their best professional judgment were the highest priority landscapes in the Portland-Vancouver region. The map was a valuable aid to prioritizing acquisition and restoration projects and the geography was right.

But, there was no “science” behind the map (below), only expert opinion.

Scaling it right

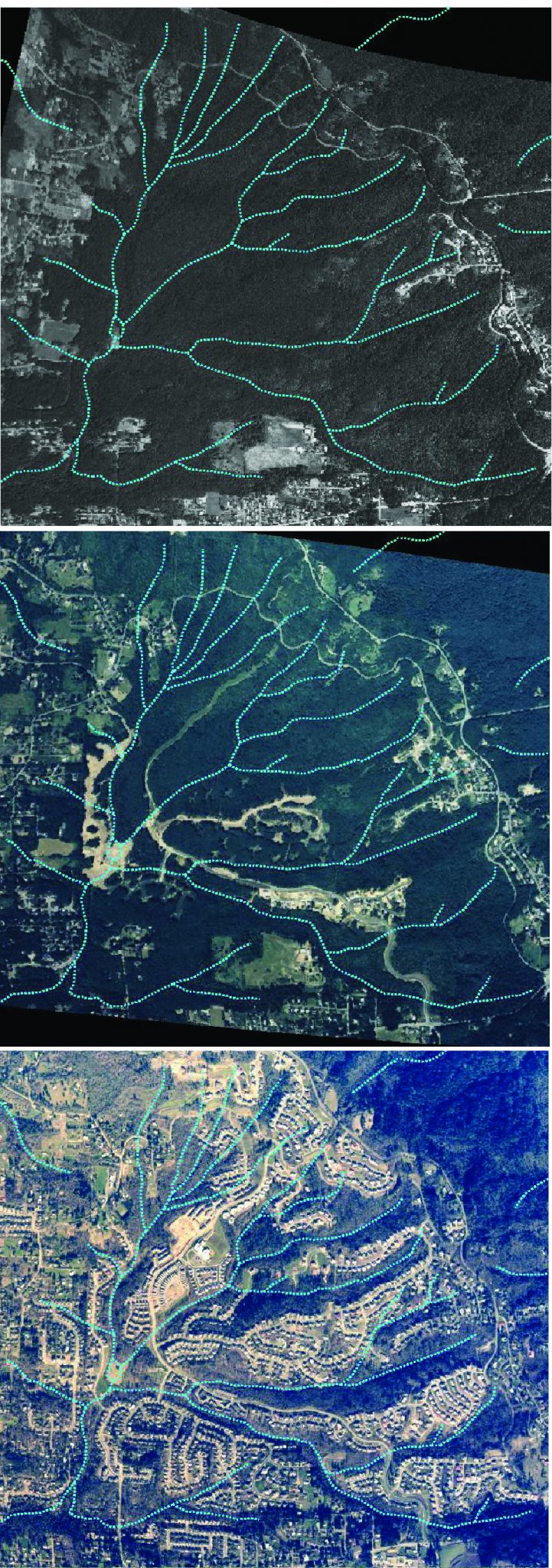

In 2010 The Intertwine Alliance launched the Regional Conservation Strategy project, which was coordinated by Alliance partner the Clark County based Columbia Land Trust. More than100 individuals and organizations collaborated on the Strategy, companion document Biodiversity Guide to the Greater Portland-Vancouver Region, high resolution, 5-meter aerial photography, and fish and wildlife habitat modeling.

In 2010 The Intertwine Alliance launched the Regional Conservation Strategy project, which was coordinated by Alliance partner the Clark County based Columbia Land Trust. More than100 individuals and organizations collaborated on the Strategy, companion document Biodiversity Guide to the Greater Portland-Vancouver Region, high resolution, 5-meter aerial photography, and fish and wildlife habitat modeling.

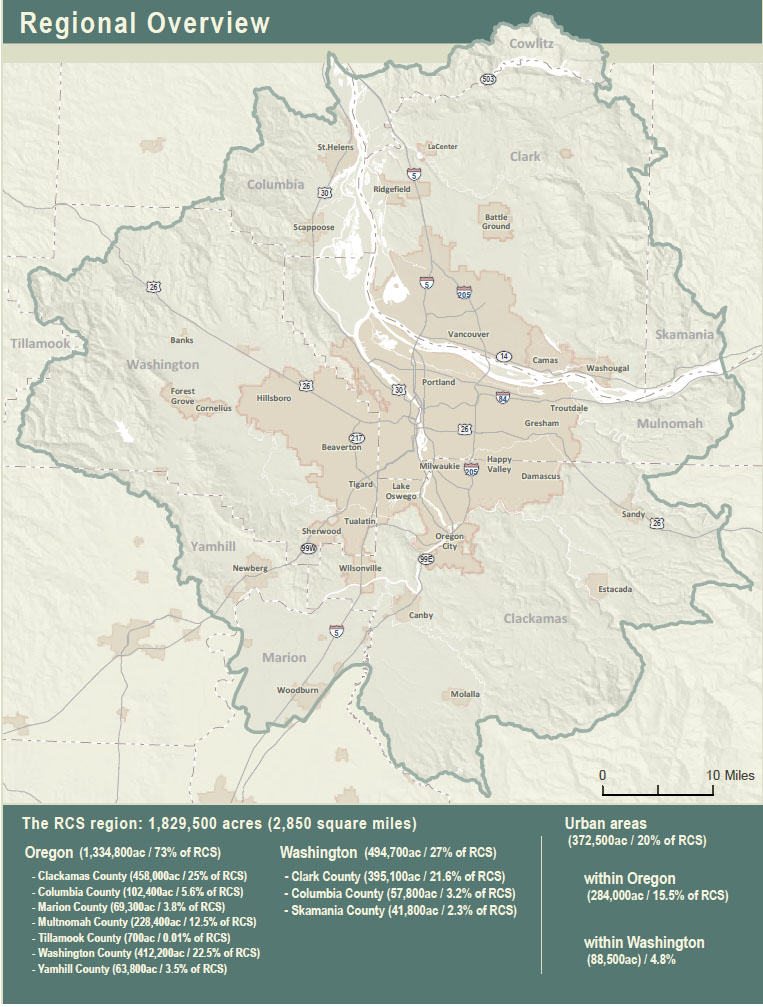

The geographic area for mapping was 2,859 square miles, including all or parts of seven Oregon and three Washington counties and 14 sub-basins (HUC 4 and HUC 5).

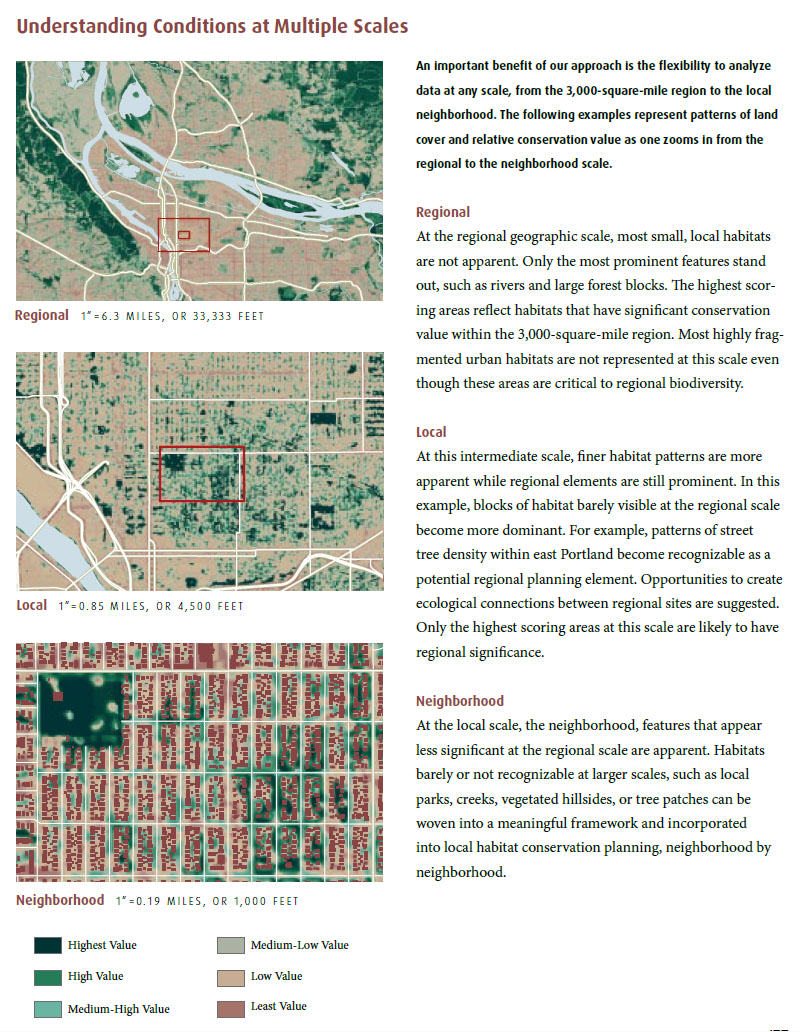

In any mapping effort the issue of database size is a critical factor. In our region, while we have imagery at the one-half meter resolution most regional mapping efforts have been at 30-meters or larger resolution, which is fine if all your are interested in is characterizing an ecoregion. If, however, you are interested in both the ecoregion and urban core higher resolution is required.

In any mapping effort the issue of database size is a critical factor. In our region, while we have imagery at the one-half meter resolution most regional mapping efforts have been at 30-meters or larger resolution, which is fine if all your are interested in is characterizing an ecoregion. If, however, you are interested in both the ecoregion and urban core higher resolution is required.

To achieve both the coarse and fine grained objective of our work the Alliance contracted with Portland State University’s Institute for Natural Resources (INR) to produce a land cover maps of the greater Portland-Vancouver region at 5-meter pixel resolution. The project mapped land cover, forest and tree patches, watersheds, and public land ownership.

To add “science” to the land cover mapping and develop a method for prioritizing acquisition and restoration across both the urban and rural landscape the Alliance developed a modeling effort that was coordinated by a GIS savvy subcommittee representing federal, state, and local jurisdictions and nonprofit organizations. The Institute for Natural Resources (INR) assumed data development and modeling approach with input from the GIS Subcommittee.

The model allows, for the first time in our region to prioritize areas of high conservation value across the 3,000 square mile urban-rural continuum, both within and outside the urban core, from the 3,000 square mile region to individual neighborhoods and the streetscape.

The model provides more detail than any previous mapping effort. Interestingly, when areas of highest biodiversity potential from the Biodiversity Guide are compared with the earlier 2006 “expert panel” map there is virtual overlap between what the model predicts with regard to highest priority habitats and what a panel of experts all of whom were knowledgable about the region indicated where their highest priority landscapes for protection and restoration.

Armed with the high resolution mapping and modeling results The Intertwine Alliance and its partners from nonprofit organizations and government agencies have, for the first time in the history of our region, the science-based tools to manage both the urban and rural landscapes with an aim to protect the region’s biodiversity, provide a framework for adapting to climate change, and move toward creating a world-class system of parks, trails, and natural areas for the region’s citizens to enjoy access to nature where they live, work and play.

Mike Houck

Portland, Oregon USA

_______________________________

Gerling and Kellett (2006), Skinny Streets & Green Neighborhoods, Design for Environment and Community, Island Press.

Beatley, Tim (2000) Green Urbanism, Learning from European Cities, Island Press, 38, 16, 30, 407, 35, 224.

Chicago Wilderness (1999) An Atlas of Biodiversity, Protected Land in the Chicago Region, Chicago Region Biodiversity Council, Chicago Wilderness Chicago, IL, 21.

Houck, Michael C. and Labbe, Jim (2007) Ecological Landscape: Connecting Neighborhood to City and City to Region, Metropolitan Briefing Book, Institute for Metropolitan Studies, Portland State University, 40, 44-46.

Wiley, Pam (2001), No Place for Nature, The Limits of Oregon’s Land Use Program, In Protecting Fish and Wildlife Habitat in the Willamette Valley, Defenders of Wildlife.

Olmsted, John Charles and Frederick Law Jr. (1903) Outlining a System of Parkways, Boulevards and Parks for the City of Portland, Report of the Park Board, Portland, 34, 36-68.

Metro, (1992) Greenspaces Master Plan, Metro Parks and Greenspaces Department.

Regional Conservation Strategy For The Greater Portland-Vancouver Region,The Intertwine Alliance, 2012. www.theintertwine.org

Biodiversity Guide For The Greater Portland-Vancouver Region, A companion to the Regional Conservation Strategy, The Intertwine Alliance, 2012. www.theintertwine.org.

About the Writer:

Mike Houck

Mike Houck is a founding member of The Nature of Cities and is currently a TNOC board member. He is The Urban Naturalist for the Urban Greenspaces Institute (www.urbangreenspaces.org), on the board of The Intertwine Alliance and is a member of the City of Portland’s Planning and Sustainability Commission.

Thanks!

http://oregonstate.edu/inr/who-we-are

I think you have the wrong link posted for INR