If you are like me, when walking in some neighborhoods, you see the endless yards of turfgrass and exotic plants and you think to yourself, “How can I reach people to change their landscaping practices?” Or you may see natural areas impacted by nearby urban areas, such as ATV vehicles and trails running through natural areas and/or perhaps invasive exotic plants escaping from nearby yards and spreading into natural areas. You think to yourself, “How can I reach residents to change behaviors that are impacting natural areas?”

In particular, I think that green developments need informed and engaged residents in order to retain the biodiversity value of a site. Even in green developments that are designed to conserve biodiversity through native landscaping and conservation of natural areas, homeowners are no different than homeowners of conventional developments in terms of environmental attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors; all tended to score low (Youngentob and Hostetler 2005). There is always a potential to compromise the biological integrity of a green development (Hostetler 2010; Hostetler and Drake 2009). Imagine residents removing native landscaping and putting in turfgrass or planting invasive exotics in their yards.

The good news is that landscaping practices in yards can improve both native flora and fauna diversity. For example, a study in Chicago found that the cumulative impact of individual yards that contained greater amounts wildlife habitat (e.g., native trees, vertical height structure, and plants with fruits and berries) had increased native bird diversity, especially for migrants (Belaire et al. 2014). Other studies have indicated that the characteristics of yards can improve the biodiversity measures in neighborhoods and cities (Hostetler and Holling 2000; Daniels and Kirkpatrick 2006; Lerman and Warren 2011).

I do not think that people want to harm the environment. It is just that they do not have information readily available that increases their awareness and empowers them to change behaviors. In this essay, I will discuss how signs installed in neighborhoods can be a technique to inform residents about conservation issues and engage residents to adopt new practices.

How can we foster the adoption of conservation practices that both improve the biodiversity value of neighborhoods while minimizing impacts stemming from residential neighborhoods?

Creating a new norm: using signs to inform residents about conservation issues

One technique to engage and inform residents about biodiversity conservation is to install educational signs into common spaces of neighborhoods. These signs could discuss a variety of conservation issues pertaining to homes, yards, and neighborhoods such as biodiversity conservation, water and energy conservation, and even information about particular wildlife species. Below, I will discuss my experiences with creating and installing such educational signs.

I. Design and management of signs

About 15 years ago I started to think about using signs, which I have seen in national parks, to reach homeowners in neighborhoods. In national parks, people only see these signs a few times. In neighborhoods, people would encounter neighborhood signs multiple times and the information would feel repetitive. My idea for neighborhood signs was to create a sign that allowed educational information to be easily updated. I have found that interchangeable education panels that insert into the “sign”–technically called a graphic display unit–were critical for several reasons. First, because the same content that people see day-to-day becomes boring or even outdated, I wanted the ability to keep information fresh and to allow educational topics to rotate. Also, in Florida and elsewhere, the panels eventually fade (or are even damaged by vandals) and I wanted a cheap way to replace them. If you use a sign that is not interchangeable, if it gets damaged or content fades over time, one has to replace the whole unit. This is very expensive! Switching out panels is more cost effective because the panels are easier to reproduce.

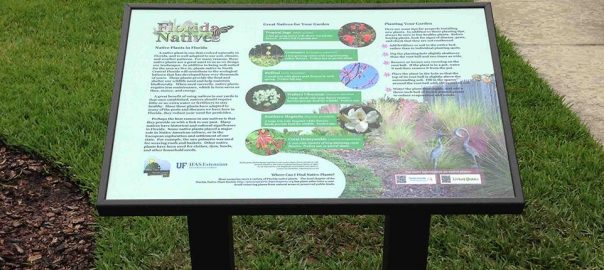

Where does one get a graphic display unit that allows educational panels to be switched out? We tried several models, but I like the one below the best (see below images). The top of the display unit can be taken off and an educational panel slid into place. To learn more about this type of graphic display unit and educational panels, see this example from Pannier Graphics. I am not endorsing this company as there are others out there, but it took me a while to find a display unit that was durable and interchangeable.

The panels are usually printed on a hard media (e.g., aluminum backing) with a clear overlaminate to protect from fading and scratches. We went with a local sign company that agreed to print full color (35” X 23”) panels on 3mm aluminum backing with a clear overlaminate for about $100 each. Once printed, the panels are endlessly interchangeable. For this neighborhood in Gainesville, we had one display unit near a pool (see photo below) and the other by a sidewalk along a road where children are picked up by a school bus (see photo above). I would recommend allocating the “switching” responsibility to a local neighborhood club, the homeowner association, or to a diligent homeowner. We have found that turning over responsibility of the upkeep of the signs to the neighborhood helps to foster ownership of the signs (not to mention that it reduces the number of trips you have to make to a neighborhood!). Further, panels need to be reprinted and new ones made; thus, I would have a long-term funding source, such as homeowner association dues, set aside for sign upkeep.

Printing posters that just have overlaminate on them and are not “hard” is also an option, but one can bend these panels easily. These work OK, but they do tend to “bubble up” and warp just a bit under the hot sun (over time). I recommend getting a sturdy backing, such as aluminum or some hard plastic composite, which will resist buckling and warping. If you do print on thinner media, you will need to place some hard backing behind the thin panel to make the space “tight” in the slot so that the panel does not slide around.

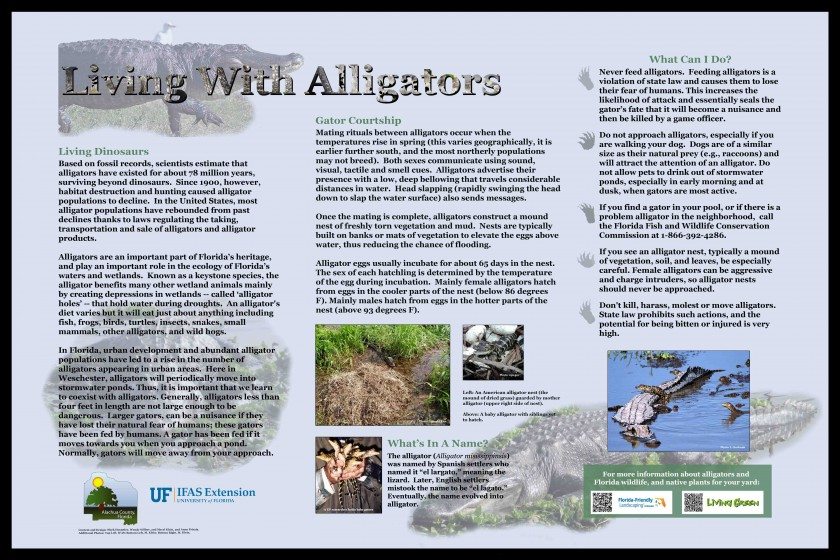

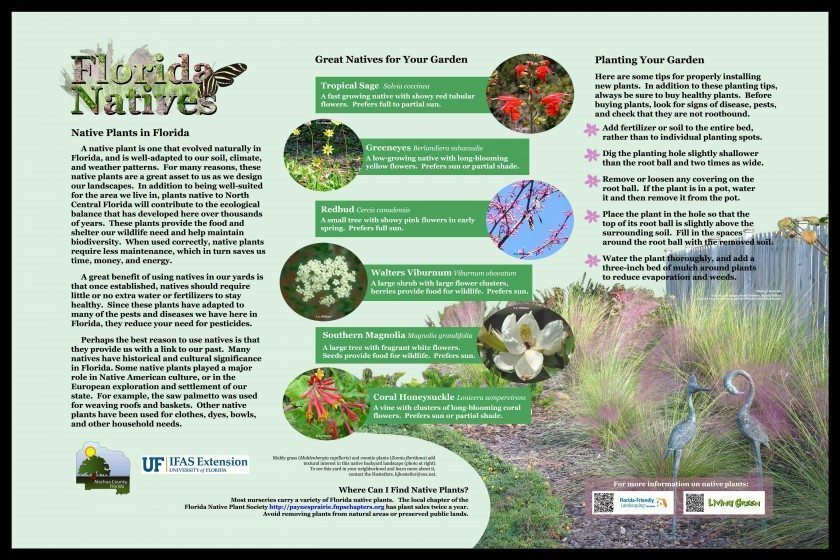

You can organize content the way you like, but we found that information organized in three sections seems to offer a variety of information in a readable way. The first section is usually a little background information about the topic; the middle section highlights an interesting fact or goes more in depth about an issue, and the third section is usually a “What You Can Do” or “Tips” section. The alligator panel above gives background information (left section) about alligators and the issue of them living in urban areas. The middle section highlights some interesting facts about alligators (courtship and nesting), while the right section talks about what people can do to reduce conflicts with alligators.

We also printed QR codes for people to scan to access more information on a Web site. On the alligator panel, the lower right area has two QR codes: one for a Living Green Web site and the other for a Florida-Friendly Landscaping Web site. We wanted to count the number of visits to these Web sites as a result of people scanning the signs in the neighborhood; there is a procedure for this. Instead of describing this process in detail, instructions can be found here. We made different QR codes for different developments so that we could track where the site visits were coming from.

As for the graphic display unit itself, we had tried some wood backing and wood posts, but I would encourage folks to install an all-aluminum graphic display unit. It is much more durable and sturdy. A couple of signs that we installed with a wood backing are beginning to break down after 7 years (not bad though!). The all-aluminum framing versions are very sturdy. I recommend installing more than one graphic display unit in different areas of a neighborhood in order to display more information. In the Town of Harmony, Florida, we installed 7 signs and each one tended to have a theme (e.g., water, energy, wildlife, landscaping, insects/pollinators, lakes, and natural/human history). Readers may wonder whether these neighborhood signs were vandalized; rates of damage appear to depend on the neighborhood. We had signs in the Town of Harmony for over 8 years with no significant damage from residents.

Still, I cannot stress enough the importance of turning over the “responsibility” of the signs to the neighborhood. Extra panels need to be stored somewhere and I recommend finding one or two local homeowners to watch the display units and to switch out the education panels. Also, any local landscaping companies need to be informed and aware about upkeep of the signs. Weed whacking around the base of these signs can cause significant damage, as can lawn care procedures around the signs. In particular, the example I showed above (the water-wise landscaping sign) has been significantly “soiled” by a pair of northern mockingbirds. They have taken to perching on the sign and defecating on it at will. When a lawn care person comes by, it is a simple matter of wiping the bird poop off the sign every now and then. Ahh well . . . . at least the mockingbirds like the sign!

II. Highlighting a Local Steward

One twist on the signs is to find a resident in the neighborhood that has implemented conservation practices and to highlight these on the panel, inviting people to contact this homeowner or to visit their yard. The trick is to find that maverick homeowner that has done something different and is willing to talk with neighbors.

We have just installed this educational sign and will follow-up with the homeowners to see if anybody has contacted them about their yard and have whether any neighbors have begun to install native plants. The hope is that a local, knowledgeable homeowner can encourage change much better than outside experts coming in and talking with only a few residents.

III. Do these signs work?

Is all this effort having a positive impact in terms of improved environmental attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors? In a study with my graduate students, we evaluated the impact of a new environmental education program installed in a green community, Town of Harmony, Florida. The study implemented educational signs, a website, and a brochure; after installation, we evaluated whether Harmony residents’ environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors improved when compared to residents of a conventional community. After two years of exposure to the program, Harmony homeowners did show some improvement in environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors and the control community did not (Hostetler et al., 2008). In particular, we found that most residents saw and read the educational signs and relatively fewer homeowners visited the website and/or read the brochure. Such signs can help homeowners understand ways to manage their homes, yards, and neighborhoods in a more sustainable manner. To see more examples of these signs, visit http://www.wec.ufl.edu/extension/gc/harmony/documents/wildsidewalk.pdf.

IV. Conclusions

As we move forward with attempts to adopt biodiversity conservation designs in urban communities, we must not forget the need to engage the local populace. The ecological function of urban natural remnants and the long-term viability of conservation design and management practices in homes, yards, and neighborhoods are contingent on how engaged and accepting residents are within cities. I encourage municipalities to create policies that require or provide incentives to install such educational signs, particularly in “green developments” that have intentions to conserve natural resources. Also, these informative signs should be installed in neighborhoods and city parks that are immediately adjacent to critical natural areas, informing users on behaviors that could have both positive and negative consequences.

I do understand that these educational signs may be only one step down a path towards a sustainable community, and signs may not be enough if there are significant barriers in city policies and even in deed restrictions placed on homes in a neighborhood. For example, some deed restrictions require that 60 percent of land in the front of a home is lawn, a condition monitored by a homeowner association. The signs may raise awareness and confidence for homeowners to implement conservation actions (e.g., planting natives), but if significant barriers exist in city or in homeowner association oversight, actions may be limited.

I hope I have highlighted some important steps to take in order to install a successful and long-lasting sign/education program to help engage residents to conserve natural resources. If you would like more information or want to collaborate on implementing such a program, please contact me, as we have streamlined the process and it is adaptable to most urban situations.

Mark Hostetler

Gainesville

References

Belaire, J.A., Whelan, C.J., and E.S. Minor. 2014. Having our yards and sharing them too: the collective effects of yards on native bird species in an urban landscape. Ecological Applications 24(8): 2132-2143.

Daniels, G. D., and J. B. Kirkpatrick. 2006. Does variation in garden characteristics influence the conservation of birds in suburbia? Biological Conservation 133:326–335.

Hostetler, M., Swiman, E., Prizzia, A., and Noiseux, K. 2008. Reaching residents of green communities: Evaluation of a unique environmental education program. Applied Environmental Education & Communication 7(3):114-124.

Hostetler, M.E. 2010. Beyond design: the importance of construction and post-construction phases in green developments. Sustainability 2:1128-1137.

Hostetler, M., and C. S. Holling. 2000. Detecting the scales at which birds respond to structure in urban landscapes. Urban Ecosystems 4:25–54.

Lerman, S. B., and P. S. Warren. 2011. The conservation value of residential yards: linking birds and people. Ecological Applications 21(4):1327–1339.

Widows, S.A. and D. Drake. 2014 Evaluating the National Wildlife Federation’s certified wildlife habitatTM program. Landscape and Urban Planning 129: 32–43

Leave a Reply