About the Writer:

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom were both giants in their impact on how we think about communities, cities, and common resources such as space and nature. But we don’t often put them together to recognize the common threads in their ideas.

Jacobs is rightly famous for her books, including The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and for her belief that people, vibrant spaces and small-scale interactions make great cities—that cities are “living beings” and function like ecosystems. Ostrom won a Nobel Prize for her work in economic governance, especially as it relates to the Commons. She was an early developer of a social-ecological framework for the governance of natural resources and ecosystems.

These streams of ideas clearly resonate together in how they bind people, economies, places, and nature into a single, ecosystem-driven framework of thought and planning—themes that deeply motivate The Nature of Cities. In this roundtable, we ask 16 people to talk about some key ideas that motivate their work, and how these ideas have roots in the ideas of either Jacobs or Ostrom, or both.

For more of their ideas, directly from them, good places to start are:

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York, USA.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

About the Writer:

Paul Downton

Writer, architect, urban evolutionary, founding convener of Urban Ecology Australia and a recognised ‘ecocity pioneer’. Paul has championed ecological cities for years but has become disenchanted with how such a beautiful concept can be perverted and misinterpreted – ‘Neom' anyone? Paul is nevertheless working on an artistic/publishing project with the working title ‘The Wild Cities’ coming soon to a crowd-funding site near you!

Paul Downton

Under the Influence

I confess, I knew little about Elinor Ostrom before being invited to join in this roundtable, but I did know something about Jane Jacobs.

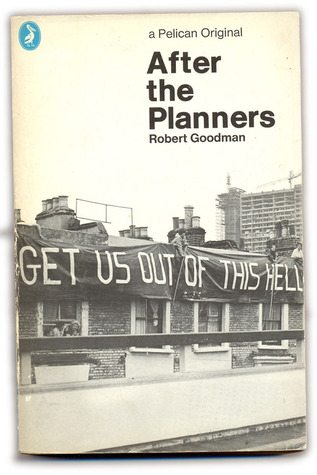

Great ideas affect many more people than the few who study them directly and this must be particularly true of the work of Jacobs and Ostrom. Whole urban populations have felt the Jacobean effect who have never heard of her. As a student of architecture in Cardiff, Wales, it was years before I knew much about Jane Jacobs directly, but her ideas and influence reached me even before I’d graduated, as I learned about Jacobs indirectly, reading Robert Goodman’s After the Planners in the early 70s.

Goodman followed in Jacobs’ footsteps, denouncing bureaucratic post-war planning experiments for their impact on local communities. His approach was polemical and overtly political and suited to the mood of its times—a mood informed by what Jacobs had published a decade earlier. It was a time when growing alienation in the public realm was accompanied by the dawning awareness that professionals were not as neutral as they presented themselves to be.

Looking back at this early history, I guess the key idea that I took from my Jacobean/Goodman reading was that planning and development are intertwined and intrinsically political, and the results of that entanglement invariably lead to power struggles in which the ascendancy of money and vested interests are guaranteed. As a corollary of that, any success in the planning system that the community might enjoy was likely to be peripheral and only achievable by the community organising to mount directly political attacks on the process itself. That made sense to me in the 1970s. It still does.

As a recently graduated architecture student, I supported the group in my city that was most heavily involved in challenging the local version of “demolish and develop”. “Cardiff Housing Action Group” was made up of concerned citizens who fought against plans for the demolition of homes and communities and their replacement by—mostly—high-rise office buildings.

In 1976-77 I worked with Bob Dumbleton, titular leader of the group, producing the illustrations and doing the paste-up for his booklet about planning and development in South Wales called ‘The Second Blitz – The demolition and rebuilding of town centres in South Wales”. I don’t remember discussing Jane Jacobs with Bob, but he must have been inspired by her work.

Tellingly, Cardiff Housing Action is still in action today, as rents rocket and housing options dwindle for ‘Generation Rent’ and the new urban poor in the UK.

The central thesis in both Goodman and Jacobs’ work, drawn from her years of working with the warp and weft of living neighbourhoods, is that community is key. If planning isn’t about people, it’s a conceit, a convenient tool used by power élites to get the development outcomes they want.

My exposure to dangerous ideas about social justice and equity in housing was paralleled and reinforced by exposure to the wild and wonderful, uber-green phenomenon of Street Farm, who embedded their vision of “people power” in landscapes of cities taken over by vegetation, where the tall, anonymous high-rise monuments to modernism were demolished by nature to make room for healthy eco-communities.

None of these influences have left me. I’ve spent my entire career giving preference to community and ecological projects and probably enjoyed fewer lucrative commissions as a result. But the one Jacobean lesson that has stuck with me through my professional career is that in an industry with unparalleled power to shape landscapes, communities, and urban futures, you have to decide whose side you’re on.

PS: I’m going to find out more about the work of Elinor Ostrom. I have a feeling I might like it.

About the Writer:

Johan Enqvist

Johan Enqvist is a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the African Climate and Development Initiative at University of Cape Town and Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University. He wants to know what makes people care.

Johan Enqvist

Making sense of diversity

“To understand cities, we have to deal outright with combinations or mixtures of uses, not separate uses, as the essential phenomena.” (Jacobs 1961, p. 188).

Cities are special. Compared to most other areas, they rely less on locally produced resources and use trade and transport to meet most of their needs. However, one resource cannot be brought in from the outside, and is consequently also often scarce in cities: space. Limited public space constitutes a “commons” since users cannot easily be excluded, and one person’s use reduces the availability for others.

Public space in cities is under pressure not only from those who want to acquire it for development, but also from being used for several different purposes by different people. A waterfront can be a gym, a science classroom, a bathroom, or a theatre; a park can be a place to forage for mushrooms, meditate, or meet friends for a picnic. In Jane Jacobs’ (1961) view, more diverse use of public spaces is better since it means people are present during more times of the day, which improves safety and promotes vibrant city neighborhoods.

But how can public spaces be managed when there are several different ideas of what their purpose should be? And how does this effect non-human “users” of a place—are diverse neighborhoods better at creating and protecting nature in cities?

In her insightful work on how to govern the commons, Elinor Ostrom (1990) joined Jacobs in arguing for the capacity and competence of local communities to determine what is best for their community. A city’s residents are the foremost experts on how their environments function, which is essential information for administrators (Jacobs 1961). With effective communication and enough trust, local communities can create norms, rules, and property rights systems to equitably manage scarce resources (Ostrom 1990). But how do you trust someone who insists on riding their jet ski in the river where you have rowing practice? Do you dare to confront the drunkards using your favorite park as a bathroom? What is the right way to communicate that you disapprove of someone washing their clothes or fishing in the lake where you want to watch birds?

These are all real examples of dilemmas faced by people I have interviewed in Bangalore and New York, where residents have come together to form groups to protect, restore, manage, or improve access to natural areas in and around water bodies. Both cities are great examples of how diversity can manifest in very different ways depending on culture, wealth, religion, age, and local traditions.

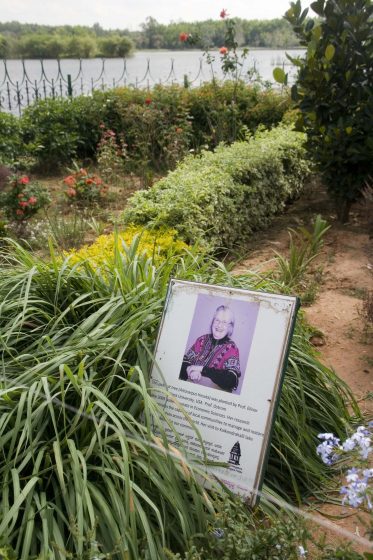

They are also places where access to water bodies has been severely limited (considering the hundreds of miles of waterfront in New York, and hundreds of lakes in Bangalore), but where local groups are actively engaged in restoring both quality of and access to waters (Picture 1). My current research, conducted with help from master’s student Ailbhe Murphy at Stockholm Resilience Centre, unpacks how different ideas about “what a place is for” relate to how individuals’ engage in such groups.

As pointed out recently by Saskia Sassen in the Guardian, and Harini Nagendra in this roundtable, Jacobs and Ostrom teach us that sense of place is key for understanding cities. But sense of place varies—two people can be equally attached to the same place even though that place means different things to each of them. This is why we believe it is important to see what civic engagement looks like at the individual level, how it relates to personally or collectively held place meanings, and if diversity in sense of place presents a problem or serves as an asset for groups trying to create effective institutions for managing these places. To me, this is a great example of how Ostrom’s and Jacobs’ ideas influence current research about how urban dwellers negotiate conflicting claims on public space in order to create vibrant and loved places within their communities (Picture 2).

References:

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York, USA.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

About the Writer:

Sheila Foster

Sheila R. Foster is a Professor of Law and Public Policy (joint appointment with McCourt School of Public Policy) at Georgetown University. Professor Foster is the author of numerous books, book chapters, and law journal articles on property, land use, environmental law, and antidiscrimination law.

Sheila Foster

If cities are the places where most of the world’s population will be living in the next century, as is predicted, it is not surprising that they have become sites of contestation over use and access to urban land, open space, infrastructure, and culture. The question posed by Saskia Sassen in a recent essay—“Who owns the city?”—is arguably at the root of these contestations and of social movements that resist the enclosure of cities by economic elites.

One answer to the question of who owns the city is that we all do. In my work I argue that the city is a common good or a “commons”—a shared resource that belongs to the collective, unorganized public. I have been writing about the urban commons for the last decade, very much inspired by the work of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom. The idea of the urban commons captures the ecological view of the city that characterizes Jane Jacobs’ classic work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. It also builds on Elinor Ostrom’s finding that common resources are capable of being collaborative managed by their users in ways that support their needs, yet sustain the resource over the long run.

Jacobs analyzed cities as complex, organic systems and observed the activity within them at the neighborhood and street levels, much like an ecologist would study natural habitats and the species interacting within them. She emphasized the diversity of land use, of people and neighborhoods, and the interaction among them, as important to maintaining the ecological balance of urban life in great cities like New York. Jacob’s critique of the urban renewal slum clearance programs of the 1940s and 50s in the United States was focused not just on the destruction of physical neighborhoods, but also on the destruction of the “irreplaceable social capital”—the networks of residents who build and strengthen working relationships over time through trust and voluntary cooperation—necessary for “self-governance” of urban neighborhoods. As political scientist Douglas Rae has written, this social capital is the “civic fauna” of urbanism.

This social capital—the norms and networks of trust and voluntary cooperation—is also at the core of urban “commoning”. The term commoning, popularized by historian Peter Linsbaugh, captures the relationship between physical resources and the communities that live near them, utilize and depend on them for essential human needs and human flourishing. In other words, much of what gives a particular urban resource its value, and normative valence, is the function of the human activity and social network in which the resource is situated. As such, disputes over the destruction or loss of community gardens, of open and green spaces, and of spaces for small scale commercial and artistic activity are really disputes about the right to access and use (or share) urban resources like vacant lots, abandoned and underutilized structures, and buildings, to provide goods necessary for human flourishing.

The urban commons framework also begs the question to which Elinor Ostrom’s work provides an intriguing answer. Recognizing that there are many tangible and intangible urban resources on which differently situated individuals and communities depend to meet a variety of human needs, what are the possibilities of bringing more collaborative governance tools to decisions about how city space and common goods are used, who has access to them, and how their resources are allocated and distributed? Is it possible to effectively manage common resources without privatizing them or exercising monopolistic public regulatory control over them, especially given that regulators tendency to be captured by economic elites?

Ostrom’s groundbreaking work demonstrated that there are options for commons management that are neither exclusively public nor private. She found examples all over the world of resource users cooperatively managing a range of natural resources—land, fisheries, and forests—using “rich mixtures of public and private instrumentalities”. In many of these examples, users work with government agencies and public officials to design, enforce, and monitor the rules for using and managing the resource. Ostrom called this kind of decision making “polycentric” to capture the idea that while the government remains an essential player in facilitating, supporting, and even supplying the necessary tools to govern shared resources, the government is not the monopoly decision maker.

What might it look like to bring more polycentric tools to govern the city, or parts of the city, as a commons? How might local government officials become facilitators or enablers of more inclusive and collaborative decision-making and, hopefully, more equitable distribution of resources to support the needs of a broader swath of its residents? A number of researchers, including myself, are working on these questions and experimenting in cities around the world with forms of urban collaborative, polycentric governance. These efforts undoubtedly owe a great debt to Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom.

About the Writer:

Lisa Gansky

At her core, Lisa is a marketect and "impact junky" with a strong interest in breaking the edges of formerly happy business models and bringing together not-so-likely characters in the form of new offerings, teams and partnerships. She is also the author of "The Mesh: Why the Future of Business is Sharing".

Lisa Gansky

Unleashing The WE To Reclaim Our Cities

Something quiet and massive happened right in the middle of the 20th century: our cities stopped truly being “ours”. Thanks to a postwar economic boom, money and ownership became synonymous with value and status. Anything that couldn’t easily be mass produced—think beauty, nature, health, belonging, peace and happiness—lingered either unrecognized or, for most, out of reach. In a shift that ran counter to the very essence of a city, what benefitted and mattered to the many took the far back seat to what was held precious by the few.

The umbrella of the commons includes raw materials like clean air and water, as well as the natural, intellectual and spiritual rights that inherently belong to all beings. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, our community scope had a much narrower focus and what we shared was of far greater value than anything each of us may have individually owned or desired. Success and happiness were shaped by how we all were doing, and our concept of “self” was us, not me. Welcome to the pronoun crisis.

Concurrent with the 2008 recession, people around the world began waking up and shaking off the tolerance for inequality and waning societal voice. We are all connected, and technology has played a pivotal role in making that essential reality undeniably conspicuous. In an age where climate challenges can fiercely and suddenly rearrange human existence, we are forced to acknowledge that we exist within a global society. The fantasy of the self as a unit has gone from creating a sense of security to unveiling intense vulnerability. Our connectedness is our most crucial gift, if we embrace it.

In the 20th century, most of humanity awoke into a finite game. The basic concept of a finite game is that to win, you must acquire more than me—in fact, you seek to gain from everyone everywhere. If you’re getting a Monopoly vibe, you’re on the right track, because the finite game is the very definition of “winner takes all”. So last century! In 2016, we are at the beginning of a societal shift in our Social Operating System—that is, we are rapidly adopting new aspirations, expectations and desires driven by a change in the core organizing principles of learning, work, communities and governments. We’re evolving towards the Infinite Game, where “winning” means you work to keep the most people in the game for as long as possible, and real success manifests in the game that never ends.

Interdependence

As we embark on an era of climate challenges, urban population explosion, institutional distrust, and massive philosophical polarity by citizens from Delhi to Dubai and Paris to Philadelphia, we are in the midst of a dissolution of institutional power and the rebirth of the commons. People around the world are conspicuously connected and are finding their voice unleashing the we that’s been idly enduring for decades. Nuit Debout gatherings spontaneously held nightly in Paris, rekindle public discourse while physically occupying the city’s commons—every pubic square, park and crevice holds the promise of reuniting people with a shared passion for creating community, animating citizenship and provoking unbounded participation.

Over the past eight years, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with instigators from cities everywhere. Ouishare, a French born collective of vocal, creative and inspired people, have convened thousands of people to explore topics like the new face of work, collaborative design, tools for creative autonomy and are growing their international community quite organically and powerfully. Ouishare has created alliances with governments, large established corporations, WEF’s global shapers network and vital pockets of inspiration like Enspiral. More than any other community on the planet, I’ve been equally delighted and priviledged to conspire and learn from the fertile substrate that is Ouishare.

About the Writer:

Mathieu Hélie

Mathieu Hélie is a software developer on weekdays and a complexity scientist and urbanist on weekends. He publishes the blog EmergentUrbanism.com .

Mathieu Hélie

When I first encountered Jane Jacobs, I was a young student of economics being taught the conventional models of neoclassical economics, models whose purpose was to describe equilibrium states of the economy, or economic perfection.

The contents of Death and Life of Great American Cities, as well as the follow-ups, The Economy of Cities and Cities and the Wealth of Nations, described an economic theory based not on perfection but on change. Through simple observation, Jane Jacobs detailed how the process of capital accumulation, both social and industrial, transformed cities towards greater wealth. She described how the variety of buildings and industries in a city, through a process by which the city’s physical and social structure adapts to itself iteratively, was the reason for its success. And ultimately, she proved how attempts to design an architecturally and economically perfect city, a city that has reached equilibrium, were pointless and self-destructive.

But if cities are impossible to architect to perfection, are we condemned to suffer total randomness and noise in urban space? While this was the proposition that Rem Koolhaas held in his analysis of postmodern urbanism, Jane Jacobs foresaw the rise of a new science of multivariable problems and solutions, to which she dedicated the last chapter of Death and Life, and which has arisen in our time under the umbrella term complexity science.

What kind of solution does complexity science offer to the kind of problem a city is? The phenomenon of emergence. Emergence occurs when many individuals collaborate and form links, connecting their collective efforts into a superstructure that supports their life and growth. It has been observed in termites, in simple computer programs called cellular automata, and it can also be observed in the world’s most attractive towns and cities, built by many cooperating individuals over centuries of changing economic fortunes and technologies.

In these urban spaces, the connections formed by building acts over decades and centuries to create an increasingly complex landscape. Examples such as the Greek island of Santorini, or the inner city of Paris, show that emergent patterns of symmetry can generate long chains of harmonious spaces that attract residents and visitors, while providing for the perfectly adapted diversity of buildings and uses that are necessary for a city to be alive and growing.

If we can observe this phenomenon of emergence in historic cities, how can it be applied in modern cities? This is where the work of Elinor Ostrom becomes relevant. Ostrom, like Jacobs, enlarged the language of economics from its neoclassical orthodoxy by suggesting that public (state-provided) and private (market-provided) goods were not the only possible categories of economic goods, but that “common pool resources” also existed, where resources were too large and too variable to be efficiently subdivided, but could be produced through collaborating appropriators.

Emergent cities, I believe, are made through such collaborations by neighbors, similar to how emergent patterns are formed by neighbors in some cellular automata. The conditions described by Ostrom for the successful management of common pool resources could be the missing urban governance model that generates complex towns and cities.

About the Writer:

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Natural forest fragments within cities can be regarded as common-pool resources (CPRs) in that they are resources “used” by a wide variety of people. CPR is a term first coined by Elinor Ostrom, and city parks fit this definition because they are frequented by hikers, joggers, wildlife watchers and nature enthusiasts, and pet walkers.

At the same time, these city forests provide habitat for a variety of wildlife species, including birds, mammals, and insects. While this common-pool resource is owned by local or state governments, these forested areas are really self-managed by the local community, and day-to-day decisions by citizens can have substantial impacts on whether the forests continue to provide viable wildlife habitat. Thus, these forests are common property systems that need to be governed by common property protocols. An ecological balance can be achieved where people can recreate while maintaining the integrity of wildlife habitat.

Elinor Ostrom studied a variety of common-pool resources, such as grazing lands, and demonstrated and championed the idea that these resources can be successfully managed by the people using them instead of being managed solely through a government institution. For forest parks and other semi-natural conserved areas in cities, there needs to be an engaged community in order to promote the conservation of wildlife habitat. Daily use by various people, living nearby and elsewhere, can have dramatically negative impacts on wildlife habitat. As I have previously argued, imagine ATV vehicles running off the trails into the forest and people letting dogs run off leash. Cumulatively, these individual decisions can destroy wildlife habitat and disrupt foraging and breeding activities of wildlife in these parks.

Thus, how do we promote “win-win” situations where these parks are enjoyed by the local populace and inhabited by a diversity of flora and fauna species? City park managers can create policies that are designed to “regulate” users to prevent misuse of the parks, such as for illegal dumping of trash. However, policing the parks, especially with limited funding and personnel, is not realistic in many cities around the world. Thus, users of the park need to cooperate on a level where their collective actions create sustainable recreation activities that minimize impacts on wildlife populations.

This cooperative governance, as advocated by Elinor, works if stakeholders are motivated by an economic return and have access to information about the consequences of their actions. For example, livestock owners, in a commonly used pasture, must be able to estimate the carrying capacity of the pasture and have an adequate monitoring system that indicates when the area is overstocked. In city parks, an economically motivated and informed populace does not exist. No direct economic return comes back to the users, and most do not know the consequence of their actions concerning the ecological integrity of a park.

This is a conundrum. Most cities cannot “regulate” all the users of the park and, collectively, users have neither the economic motivation nor ecological understanding of the consequences of their actions. How to create a societal “norm” where citizens recreate in parks in a sustainable manner?

I would suggest that city parks need to have educational programs that speak to sustainable behaviors, both in and outside of the parks. Sustainable behaviors include everything from staying on the trails to actions people take within their own yards and neighborhoods located next to parks (for details, click here). For instance, an active colony of feral cats in a nearby neighborhood could have huge consequences for wildlife in a park. Nearby neighborhoods should have educational opportunities to learn about connections between management of neighborhoods and their potential impacts on parks. In addition, “Friends of [a named park]” or such voluntary groups should be established, giving opportunities for citizens to help maintain and even restore sections of a park. These activities will help promote “ownership” of the park and create a functional, cooperative governance, along the lines of Elinor Ostrom’s work.

About the Writer:

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

Michelle Johnson

Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom are both well known for developing design principles. For Jacobs, it was design principles for planning cities that considered the interaction of physical design with social space at multiple scales. For Ostrom, it was design principles, or a set of social and ecological conditions, necessary for successful community-scale management of common pool resources.

In each case, the methods they used and the way they went about deriving these design principles are what fascinate me. Jane Jacobs wrote of the neighborhood scale, “eyes on the street”, and the way that the vitality and diversity of neighborhoods enables a city to function as a system. She understood these things through the power of observation—through essentially inductive research. Elinor Ostrom asked the question: under what conditions can common pool resources be sustainably managed by a community? She built large datasets of lists and case studies that enabled her to identify a set of conditions where sustainable management actually was possible.

Both Jacobs and Ostrom examined systems from the bottom up, using rich empirical datasets, which provided a very different picture of a system than taking a bird’s eye view. In essence, the way they approached their work enabled another way of seeing the system—of an alternative to Robert Moses’ top-down planning in New York City and Garrett Hardin’s recommendation to regulate the commons, regardless of local conditions.

It is this idea of another way of seeing that I bring to my work—both in further understanding the urban social-ecological system in which we live and also looking to the possibilities of the future. Below, I share an example of each:

Understanding the system

At the New York City Urban Field Station, I have had the good fortune to join colleagues (Erika Svendsen and Lindsay Campbell) that research urban environmental stewardship. In New York City, there are over 2,800 stewardship organizations that care for the urban environment, working from the scale of a street corner to the entire five boroughs and beyond. These organizations are working in shared public space, towards common and diverse ends, and in communication and isolation from other organizations and government. Walking down the street, however, you may not be aware of their presence. Social space can sometimes be rendered invisible in cities. A cornerstone of stewardship research in New York City is the Stewardship and Assessment Mapping Project (STEW-MAP), started in 2007. Through this project, we mapped social space alongside green space, enabling others to, in essence, “see” the presence of these stewardship organizations. Organizations responded to a survey that addressed organizational characteristics, networks, and stewardship “turfs”, or areas where organizations worked. We included the results on an online, public map at OASIS. Efforts are underway for a decadal repeat in 2017, to examine how this set of organizations engaged in environmental stewardship has changed over time—in capacity, in location, in emphasis, and in communication and exchange with others.

Possibilities for the future

Switching gears from what is to what could be—thinking about the future and what could be is a difficult task. Past research has shown that one’s idea of the future becomes very fuzzy or goes blank after 10 to 15 years in the future. Yet, planning efforts are for the long-term—many comprehensive plans look 20 to 30 years in the future. Using an alternative futures approach to planning enables a community to see other possibilities than what is. This is particularly important where a community does not want the status quo to remain. Alternative futures, or scenarios, can be in written and/or visual formats—in the forms of stories, pictures, graphs, and maps. I am interested in scenarios not just as a tool for seeing what could be, but also, perhaps, as tools for increasing the breadth and depth of discussion about the future in cities and regions. Some research of mine, soon to be available in the journal Land Use Policy, has focused on how seeing alternative futures may affect an individual’s willingness to participate in planning activities. Reading a set of scenarios increased willingness to participate, but also increased self-efficacy, the concept that one can contribute to an outcome. Because of this, I see scenarios as a communication tool with the potential to increase the diversity of those involved in planning for communities’ futures.

Perhaps both of these projects I describe here—of mapping stewardship and understanding the impact of scenarios—may also lead down the path from new ways of seeing towards contributing to design principles for cities and regions. What a lofty goal, but what great examples we have in Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom to point the way, through their demonstration of how empirically-grounded insights can lead to new understandings of social-ecological systems.

About the Writer:

Marianne Krasny

Marianne Krasny is professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Director of the Civic Ecology Lab at Cornell University, and leader of EPA’s national environmental education training program (“EECapacity”).

Marianne Krasny and Alex Russ

Search “environmental education” on Google images and you will be hard pressed to find anything that looks like a city. So what does environmental education have to do with cities, let alone Ostrom’s notions of polycentric governance?

One place to look for an answer is in recent scholarship about urban environmental education. We asked 82 scholars from 18 countries to contribute to a forthcoming textbook called the Urban Environmental Education Review (Russ and Krasny, Cornell University Press, 2017). Three themes emerged from the 30 chapters in the book: place, participation, and partnership.

Place as a theme in environmental education dates back to the turn of the 20th century. Concerned about children losing opportunities to learn from nature as farm families uprooted to cities, Cornell nature educators Anna Botsford Comstock and Liberty Hyde Bailey called for lessons to take place in urban nature. A century later, Richard Louv sounded the alarm about children spending too little time in nature in his book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder. Chapter authors in our book take the notion of place one step beyond spending time in nature. They talk about how, through engagement in hands-on community gardening, oyster restoration, and other civic ecology practices, as well as in urban planning and policy-making, environmental education participants are helping to re-construct and re-create cities and urban nature, while also developing an ecological place meaning.

Participation as a theme in urban environmental education has a more recent history. Starting in the 1970s, then-PhD student Arjen Wals was researching environmental education in Detroit. He quickly realized that the curriculum developed at the University of Michigan was not going to work. His research helped launch a participatory action trend in environmental education, where youth help address local environmental problems through activities ranging from monitoring water quality to providing testimony at city council meetings. The Danes later expanded on this work, including Jeppe Laessoe, who proposed four types of participatory practices in environmental education—participation as encounters with nature, as social learning, as action, and as deliberative dialogue.

Participation in deliberative dialogue is linked to the third theme in our book—partnerships. Nearly every chapter describes the partnerships involved in conducting environmental education programs. Two chapters go one step further and explicitly focus on how environmental education organizations are actors in urban environmental governance networks. Whether the theme is intergenerational environmental education, environmental justice, or restoration-based education, the chapters mention the government, NGO, and business partners involved in the work.

If you gaze across the Bronx River from the youth organization Rocking the Boat, you can see Soundview Park, one of thousands of actors in green space stewardship and governance in New York City. According to Svendsen and Campbell (2008), nearly 70 percent of environmental stewardship organizations in NYC provide environmental education. Similarly, according to research of the SURGE project, a quarter of civil society organizations engaged in green space governance in 20 European cities provided education, and Enqvist has described how in Bangalore, India, one of the most important achievements cited by members of a green space governance network was raising public awareness about environmental issues.

In short, organizations that conduct environmental education are actors in governance networks in cities in Europe, India, and the U.S.—these are the very networks that form polycentric governance systems, which Ostrom demonstrated are critical to management and policy. So what does environmental education have to contribute to these environmental governance networks in cities?

We contend that environmental education is more than kids hugging trees—its participants do everything from mapping green space to documenting environmental injustices in videos, from restoring dunes to helping design pocket parks. As actors in governance networks, environmental education practitioners and scholars bring expertise in participatory approaches to addressing environmental issues, and in approaches that help residents understand and re-construct urban place—including its green infrastructure. We need to look at both sides of the river. Environmental educators can become aware of their role in governance networks—and share their insights with other governance actors (using place-based and participatory approaches). And other organizations in governance networks can seek out the expertise of environmental educators. In this way, urban environmental education can work alongside other actors to enhance Ostrom’s polycentric governance systems that are desperately needed in managing urban green space.

About the Writer:

Alex Russ

Alex Kudryavtsev (pen name: Alex Russ) is an online course instructor for EECapacity, an EPA-funded environment educator training project led by Cornell University and NAAEE.

About the Writer:

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and "Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India's Cities" (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Harini Nagendra

The importance of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom’s ideas for urban commons in new and growing cities

The rapid growth of cities is changing the world in unprecedented ways. Across the world, long-enduring, sustainable rural landscapes transform into places of flux and chaos, as millions of migrants pour in to cities as far flung as Mumbai, São Paulo, and Kinshasa. What does the work of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom—scholar-practitioners of cities, whose urban work was largely located in North America—have to say in these contexts? Quite a lot, as it turns out.

Growing cities face a challenge of the loss of community. This is particularly visible in peri-urban areas, which are self organized, and tend to lack intervention by formal urban planners. City fringes have a unique spatial character, with high fragmentation of urban land use, large fluxes of people, the domination of renters over home owners, and of recent migrants over long-term residents. Neighbourhoods are faced with the challenge of mobilising social capital for civic action in a governance gap, where city governments do little by the way of providing basic urban services.

Yet cities are also places for being exposed to, and appreciating, the new. How does one create “new commons” that enable disparate groups of migrants from different corners of the world to not just co-habit and co-exist, but also to appreciate and capitalise on their differences, using these productively to build new ideas, devise new skills, and forge new political approaches to collaboration? Here is where the work of Jane Jacobs on the importance of the home and neighbourhood in building communities and urban commons gains special importance. In low-income areas for instance, urban ecosystems tend to become locations of disservices rather than services, with water bodies becoming polluted, disease-infested sewage ponds, and groves of trees acting as rodent-infested nodes of crime and drugs, for instance. Yet in slums of Bangalore, for instance, women often expend tremendous effort to create small patches of greenery, planting shrubs with pretty flowers and sacred trees at lane crossings to brighten up their daily lives and provide shaded spaces for women to gather, play a game of cards, groom each other, and build social capital.

Certain types of urban ecosystems act as catalysts and antidotes to the loss of community, fostering a sense of place. Elinor Ostrom’s work on the commons points to the importance of local context in shaping governance of the commons. Both Ostrom’s research and Jacobs’ careful observations of city life tell us that it is for people to get involved in, and in fact to vision, drive, and shape the outcomes of urban restoration. Mere planting of trees, or restoration of degraded wetlands and lakes will not guarantee urban renewal. A good example is the much touted “Million Tree” planting initiatives in many major U.S. cities. As several cities discovered, this process was driven mostly by city governments relying heavily on short term contract labour, with the result that neighbourhoods were disengaged from this process. Planting trees purely for aesthetic reasons, or driven by seemingly abstract motivations of biodiversity, does not take into account the context-specific needs and motivations of local residents. These could be considerations of sacredness in India, or of food in South Africa, or of both in China. This is an important lesson that emerges from the writings of both Jacobs and Ostrom, both of whom were keen, astute, and engaged actors in their own communities of practice.

Community gardens are a particularly exciting example of urban renewal, where people begin with gardening but often end up going well beyond this, engaging in transformative city change via acts as diverse as community entrepreneurship and engagement with city politics. Peri-urban landscapes in growing cities, being less crowded, can offer greater possibilities of open space for community gardening in comparison to older city centres, where land availability is typically scarce. These new spatial commons can provide powerful ways to integrate disparate groups of migrants speaking different languages, with different gardening skills, into close-knit communities of practice: thereby also making cities more welcoming and livable spaces for poor migrants who may often arrive in cities under situations of distress and insecurity.

Thus, there is much that growing cities can learn from the ideas of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom. A first and important idea is that local communities often intuitively know what is best for their own environments, a fact that planning experts still refuse to recognise. Ironically, despite the lament expressed about “unplanned” urbanization in the global South, this may in fact offer unique opportunities to build sustainable local commons in new urban areas across the world. A second aspect, stressed by both Ostrom and Jacobs, is that for local commons to emerge, strong sense of place is needed, built around local socio-cultural and ecological identity. The third is the importance of co-production and of multi-level governance—of city governments to recognize that they must co-design and co-produce neighbourhoods with local communities, rather than tear down and rebuild based on supposedly modern ideas of aesthetics.

Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom pointed to the importance of getting the process right, to achieve the outcomes we desire. Growing cities represent challenges but also opportunities to do things right, if we follow the basic principles that they so clearly, and thoughtfully, outline.

About the Writer:

Raul Pacheco-Vega

Dr. Raul Pacheco-Vega is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Public Policy at CIDE in Mexico. Raul’s research is interdisciplinary by nature, lying at the intersection of space, public policy, environment, and society. He is primarily interested in understanding the factors that contribute to (or hinder) cooperation in natural resource governance.

Raul Pacheco-Vega

Two great women, two paradigms, one lasting legacy?

I am thrilled to join this global roundtable for The Nature of Cities on the topics of Elinor Ostrom and Jane Jacobs’ strong influences in how cities are built, operated, planned, designed, and lived within. Even if many people who have read Elinor Ostrom may not think that she had something to say about how cities are governed, much of her work focused on the governance of polycentric urban systems, particularly how public service delivery in metropolitan areas could pool resources and offer a more efficient model to serve citizens. Her early work on metropolitan resource allocation followed much of what her husband, Vincent Ostrom, had posited in 1961, but expanding it to resource governance made a long-lasting contribution.

Jane Jacobs is very well known for her contributions to urban planning, although much less recognized for her understanding of economic development and growth. Her legacy is undeniable, and one of the most popular models for understanding a city through walking around it, Jane’s Walks, emerged as a response to her growing influence in how we see and understand cities.

I have a personal connection to both Elinor Ostrom and Jane Jacobs, even though I only met one of them (Elinor). My connection to Jacobs derives from the fact that I am a Vancouverite (from the Main and 16th Avenue area, in Mount Pleasant), and for 20 years of my life, before moving to Mexico, I saw firsthand the results of Jane Jacobs’ influence on Vancouver’s urban form. This urban design paradigm, called Vancouverism, is one of those long-lasting legacies of Jane Jacobs. The idea of a livable city, with high-density high rise buildings, mixed-use neighbourhoods and walkable areas, short distances to work, and sustainable transit, is at the core of the Vancouverism paradigm. Most importantly, Vancouverism as a legacy of Jane Jacobs is a way of looking at urban planning and urban design that integrates human beings and their needs at the core of the planning process. That said, and contrary to the legacy of Elinor Ostrom, Vancouverism has become a model of designing cities that has all but forgotten the need for collaborative processes to understand individual needs. Vancouver is considered one of the most (if not THE most) unaffordable cities in the world. How could a city that is so focused on being “livable” end up becoming one of the least affordable? Would Jane Jacobs agree with this unintended result of her teachings?

I met Elinor Ostrom and Vincent Ostrom on a sunny afternoon in 2002, when they visited Vancouver and The University of British Columbia and spent time there as visiting professors. I went out for lunch with the Ostroms and spent hours pondering the musings of common pool resource theory: the crazy idea that communities and entire societies were able to collaborate and cooperate amongst themselves to avoid excessive overconsumption and resource depletion. Elinor Ostrom demonstrated that for many resources, cooperation was possible by creating a collaborative framework of strong resource allocation and use rules as well as robust compliance and enforcement mechanisms. This cooperative approach would be possibly escalated at the community, city, and regional levels through polycentric governance models.

While both Elinor Ostrom and Jane Jacobs have had a very profound impact on my own work and life because of my interest and research in urban water governance, I am much more aligned with Ostrom’s work because I believe that water in cities should be governed not through a top-down paradigm (much like Vancouverism perpetuates, and much along the lines of what Jacobs would suggest), but instead through a bottom-up model where the emergence of polycentric governance is the result of collaborations across multiple stakeholders.

I celebrate both of their works, but I am keen to see whose legacy is more durable on the topic of urban planning and cities’ governance.

About the Writer:

Michael Mehaffy

Michael W Mehaffy, Ph.D., is an author, researcher, educator, and practitioner in urban design and strategic urban development, with an international practice based in Portland, Oregon.

Michael Mehaffy

Jacobs, Ostrom and the “Age of Human Capital”

Just now we are seeing a welcome reassessment of Jane Jacobs’ work, around the occasion of the 100th anniversary of her birth. Unlike previous re-assessments (e.g., on the 50th anniversary of Death and Life, her best-known book) this one does not seem to have much of a revisionist momentum. Instead it seems to take seriously the idea that there is still a lot more to unpack, and to take forward.

In part this may be because the occasion of her birthday is an unseemly moment to join in the ignorant revisionism that previously painted her as a libertarian ideologue, or a quixotic warrior against inevitable “modern” progress, or a closet racist, or an elitist who happily encouraged gentrification—depictions that are all fantasies, wholly unsupported by evidence. (I commented on these issues earlier.)

Perhaps, though, the greater insight on offer this time reflects a genuine maturing of the discourse, recognizing some commonality in our understanding of the nature of our challenges today, and Jacobs’ helpful role in clarifying them. In this consilience we can see strong parallels to the works of others, and in my own work I have explored parallels to Christopher Alexander, Bruno Latour, René Thom, Alfred North Whitehead, Henry George, and others.

To that list we can make the notable addition of Elinor Ostrom, whose work on commons-based economics, and culture, won her a Nobel Prize, among other accolades. Her model can best be described as a network of polycentric organizations whose business is managing a resource commons. There are strong parallels to Jacobs’ “web way of thinking” and to Chris Alexander’s attack on modernist planning for creating “cities as trees”, mathematically speaking. Following Alexander’s work, we might summarize Ostrom’s insights as “commons governance is not a tree”.

Ostrom did express a debt to Jacobs’ insights for her own work, and the philosophical connection between them is easy to see. Aside from the web-network approach to problem-solving, both acknowledged that economic productivity is not simply about the linear transformations of inert resources within a commons, but about how human beings interact within that physical and urban commons to create and manage the transformations, whose structure is quite complex. Jacobs’ less well known books on that economic topic are marvels of insight, building on the more directly urban insights of Death and Life.

In essence, Jacobs said, economic expansion happens as the result of creative differentiation, and that creativity is firmly rooted in the physical structure of a city (or town) and its public spaces. This is the stage for the “sidewalk ballet”, the physical anchor of the social network in which people encounter one another, are introduced to strangers, make connections, and begin the process of creating “knowledge spillovers”—the exchanges that create new syntheses and new efficiencies from existing resources. (They are now called “Jacobs Spillovers” in honor of her seminal work.)

Other networks are important too—professional, electronic, and so on—but they must supplement, and not replace, the physical system consisting of physical people and their interactions within public spaces. (This is a core reason, economically speaking, why we create cities at all.) But if we try to get rid of this core network, or fail to fully utilize its creative power, we are going to be in increasing trouble. So we are.

The alternative response—very much on display around the world today—is simply to increase the rate at which we are plundering natural assets beyond the planet’s carrying capacity. This is a miserable approach, not only because it is fundamentally unsustainable, but because it systematically degrades quality of life beyond a few pockets of momentary excess. Its urban manifestation is sprawl, what Leon Krier has called our “collective obesity.” It is the “crack cocaine” of economic development—a quick and intense high, followed by a planetary hangover.

Jacobs warned of the terrible consequences of this continued approach—not only for the depletion of resources, but for the erosion of the foundations of human institutions, and the “dark age ahead” if we do not get a handle on it (the title of her last admonitory book). Ostrom, too, pointed to the dangers of an overly rigid approach, a model of “governance as a tree,” and its increasing institutional, economic, and ecological failures.

To transition away from this unsustainable era, we are going to need powerful tools and insights, and we are lucky that Jacobs and Ostrom have offered us several of the most powerful. To them we could add, among others, Henry George and his economics of the Commons, conserved in part by a taxation system that supports increases in its creative and efficient uses. (Essentially, consumption of resources including land is taxed more heavily than human creativity, which penalizes depletion and waste, and rewards doing more with less.) We urgently need these systemic changes to our economic feedback systems, especially around so-called “externalities”, as Jacobs and Ostrom both pointed out.

When she died, Jacobs was known to be working on a book with the subject of “the coming age of human capital”. By that she seemed to mean, the age in which we will replace the stripping of massive quantities of natural resources out of the Earth at unsustainable rates, with the creation of a no less prosperous time—indeed a more prosperous time, because it will focus on true prosperity: the ability to live a fulfilling life of creative richness and beauty, within our own means. We had better get to work on that essential goal.

About the Writer:

Mary Rowe

Mary W. Rowe is an urbanist and civic entrepreneur. She currently lives in Toronto, Canada, the traditional territories of the Anishinabewaki, Huron-Wendat and Haudenosauneega Confederacy, and works with government, business and civil society organizations to strengthen the economic, social, cultural and environmental resilience of the city and its neighborhoods.

Mary Rowe

Elinor Ostrom and Jane Jacobs, and the power of self-organization

It’s interesting that two women outside the traditional field of economics have made such remarkable contributions to our understanding of the economy. Both rose to prominence in fields dominated by men, pursuing independent careers in the 1960s, just as Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring laid out their brilliant indictments of the status quo put in place by men. Up came Jacobs and Ostrom, too, calling out the emperors in their respective domains.

Elinor Ostrom was, in fact, trained as a political scientist, having been rejected by UCLA for their PhD program in economics, because she hadn’t done the math. (We all sympathize.) She opted for political science instead, and went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics some 35 years later for her seminal work on governance models for the commons, and particularly common-pooled resources, which she eventually laid out in Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action.

Jane Jacobs had no advanced degree, other than continuing education credits from Columbia she earned while working as a magazine journalist. Her intellectual interests were famously varied; she read widely where her curiosity led, including metallurgy, geology, and biology. She went on to write arguably the most influential book on city development of the 20th century, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and then subsequent volumes on the crucial role of cities in the economy. Late in her life, there was talk about a potential nomination for the Nobel Prize, but it was seen as unfathomable that it would be bestowed on a non-academic, let alone one who perhaps only graduated high school.

The incisive trait that both these women share is their power of observation, perhaps borne from their curiosity to understand how human behavior actually works. Most strikingly, each advocated for policy approaches to their domains of interest that were predicated on the capacity of human behaviour to self-organize, regulate, and course correct, without government regulation or intrusion.

Ostrom focused on ‘common pooled resources’ like fisheries and pasture-land, and how local governance strategies could be effective in both generating needed incomes and stewarding the long term survival of the asset. Jacobs’ focus was the city, which she viewed as a commons of places and spaces and functions that made possible both productive individual lives and generative collective pursuits. Both averred grand-schemed, one-size-fits all approaches, imposed by governments at the exclusion of the particulars of every circumstance. Ostrom preferred an Adaptive Governance approach, locally tailored, where layered systems could be applied and adjusted based on results. (Resilience advocates, take note).

In her last published piece (published on the day of her death, in fact) “Green from the Grassroots”, Ostrom spoke cautiously about assuming that a global agreement on climate change from the UN Rio+20 meeting would be the answer:

“Decades of research demonstrate that a variety of overlapping policies at city, subnational, national, and international levels is more likely to succeed than are single, overarching binding agreements. Such an evolutionary approach to policy provides essential safety nets should one or more policies fail… “.

She concludes that article:

“…Worldwide, we are seeing a heterogeneous collection of cities interacting in a way that could have far-reaching influence on how Earth’s entire life-support system evolves. These cities are learning from one another, building on good ideas and jettisoning poorer ones. Los Angeles took decades to implement pollution controls, but other cities, like Beijing, converted rapidly when they saw the benefits. In the coming decades, we may see a global system of interconnected sustainable cities emerging. If successful, everyone will want to join the club”.

Hard to imagine a more Jacobean sentiment that that.

In a 1998 interview with the journal Government Technology, Jacobs said “I hate the government for making my life absurd”, which was more a pointed objection to how often government got it wrong and required citizen activism to oppose wrong-headed policies. But more fundamentally, Jacobs knew from observation, that the city and its economy behaved like an organism, and would naturally course-correct, and adapt to changing conditions, if enabled to do so. Like Ostrom, she deduced that people could in fact pursue their individual interests, while at the same time recognize the importance of collaboration and mutual trust. Government intervention was too often overly proscriptive and controlling, large-scale, and imposing general rules to particular conditions. And failing. Ostrom and Jacobs agreed: better that local communities—of fisherman, of park users, of stock exchanges—develop systems of self-organization that put in place locally-specific feedback loops to alert users that a course correction is needed.

Jacobs and Ostrom are thought leaders in understanding the particularity of human ecology, providing a badly needed bridge between the misanthropic purists of the environmental movement (who for decades have seen people as the problem, preferring they just go away…) and a more holistic understanding that places people, and their cities, as an integral part of the ecosystems they inhabit.

Following the success of Death and Life, Jacobs continued for another 40 years to explore the dynamics of contemporary life, and its economy, and the values systems that underpin and sustain it. Ostrom’s ideas gestated for years before Governing was released, and appear to have continued to evolve. How interested they both would be to see how digital technology is enabling a more prudent stewardship of common pooled resources—urban and rural—as a renewed sharing economy emerges that reduces deleterious impacts and economizes use.

To what extent was their perspective shaped by their gender? And their temperaments? And their personal experience: both experienced their greatest successes later in their careers, each writing well into the last years of their lives. I only knew Jacobs, but I wonder if Ostrom, too, saw the world with empathic eyes, trained by years of close observation?

Just as this blog continues to make clear, nature and cities are one. Cities are a product of the natural human impulse to self–organize—how we gather, and derive mutual benefit, from all that we hold in common.

About the Writer:

Laura Shillington

Laura Shillington is faculty in the Department of Geoscience and the Social Science Methods Programme at John Abbott College (Montréal). She is also a Research Associate at the Loyola Sustainability Research Centre, Concordia University (Montréal).

Laura Shillington

Everyday streets and local institutions: Jacobs and Ostrom’s everyday scales

Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom were seminal figures in their respective fields. Both were on my comprehensive reading lists for my doctoral exams—albeit for different fields. Jane Jacobs was on my list for urban geography and Elinor Ostrom for my human-environment/political ecology list. My third list was feminist geography. Seemingly disparate fields, but there were two key ideas that tied these lists together: the concepts of socio-natural relations (or socio-ecology) and scale.

As a trained feminist political ecologist, I am interested in socio-nature relations at the everyday scale. And both Jacobs and Ostrom were female scholars who paid attention to the scale of the everyday. While neither Jacobs nor Ostrom considered themselves feminist scholars, their attention to the everyday scale paralleled feminist analyses of the home, streets, city and country. Feminist geographers have long insisted that everyday spaces (such as the home and community) are intimately tied up with a myriad of relations and processes in other places and scales. Such analysis has been critical to changing the way we understand different spaces, and Ostrom and Jacobs were forerunners in showing how social-ecologies are just as scaled as the social processes that feminist scholars examined. Jacobs and Ostrom used the scale of the everyday to emphasise two key points: the importance of paying attention to the everyday scale, and the embeddedness of the everyday in larger scale processes.

Both Jacobs and Ostrom showed how the decisions and negotiations that took place at the everyday scale (the household, community and streets) were critical to understanding how the city in Jacob’s case and natural resources in Ostrom’s work are used, viewed, experienced, and managed. Jacobs wrote about the link between urban neighbourhoods and urban economics. Her everyday space was the street. The street was where the private and public spaces intersected, where diversity was created and economies born. For Jacobs, the aggregation of quotidian routines was what produced vibrant city spaces and economies. Scattered throughout her early writings were references to urban nature and the importance of these to daily life and economies in cities. She saw economies, social life, and nature as very connected and necessary for a well-functioning city:

“The more successfully a city mingles everyday diversity of uses and users in its everyday streets, the more successfully, casually (and economically) its people thereby enliven and support well-located parks that can thus give back grace and delight to their neighborhoods instead of vacuity.” —Jacobs 1992 [1961], p. 111

The neighbourhood was, for Jacobs, a key space in producing liveable, lively cities. Jacobs viewed local communities as critical resources for day-to-day well-being. She wrote about acts that took place on streets in neighbourhoods and in parks that keep them safe, lively, and diverse. Her phrase “eyes on the street” has been widely quoted. Indeed, Jacobs’ eyes on the streets can be understood as the rules and small-scale institutions in Ostrom’s work.

Ostrom’s scale of the everyday also comprised the individual and the community. She saw the community as a key player in governing society and argued that communities (of individuals) are also institutions. Ostrom was concerned about the limited definition of institutions typically used in political science (in particular based solely on the market and state) and redefined institution to include the rules and processes at work in the everyday.

“Institutions are the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structured interactions including those within families, neighborhoods, markets, firms, sports, leagues, churches, private associations, and governments at all scales” —Ostrom 2005, p. 3

Using her definition of institutions and rules, she countered Hardin’s tragedy of the commons by arguing that governing the commons is not only done by the market or state (as Hardin contends). Rather, because institutions are much more complex, diverse, and scalar, she argued that governing common resources is also done through local institutions where individuals and communities are able to create the ‘rules of the game’. Individuals and communities, Ostrom suggested, have intimate knowledge of how natural resources are understood and used on a daily basis. As such, rules created by local individuals and their institutions matter.

At the same time that they both stressed the importance of everyday life, they also recognised that everyday life was never separate from the larger scale economic and political processes. Jacobs’ early work was heavily critiqued for her lack of connection to broader processes. This is something she addresses in later works, where she makes clear links between her everyday streets and larger urban spaces and economies. Her key argument was that the stimulating effects of diverse economies and the neighbourhood scale created larger urban economies. The everyday scale caused urban economic development, which in turn produced economic development in areas outside cities. As Soja (2009) comments, Jacobs argued that cities created economic development “…not because people are smarter in cities but rather because urban densities and proximities produce a concentration of need and increased incentives to think about problems in new ways” (p. 269).

Similar to Jacobs, Ostrom also contended that local communities were very capable of managing natural resources sustainably by developing rules for extraction, appropriation, and use. She did not romanticise the community, however, and was very aware that the community was one scale in a complex landscape. In 2009, Ostrom wrote an article in Science outlining a general framework for analysing the sustainability of social-ecological systems. She argued that “all humanly used resources are embedded in complex social-ecological systems (SES),” which is shaped by interconnected scales: resource system (e.g., a coastal fishery), resource units (e.g., lobsters), users (fishers), and governance systems (organizations and rules that govern fishing on the coast)(p. 419).

The attention to the importance of the everyday scale is, in my opinion, what made Jacobs and Ostrom so influential and visionary. Without a view from the street (whether it be urban or rural), we have only a partial understanding of how socio-ecological systems function.

References:

Jacobs, J. (1992 [1961]) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2009) A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems, Science 32 (July 24): 419-422.

Soja, E. (2009) Regional Planning and Development Theories, in R. Kitchin and N. Thrift (eds) International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, pp. 259-270. Oxford: Elsevier

About the Writer:

Anne Trumble

Anne Trumble is a landscape and urban designer based in Los Angeles, where she is currently working with the Arid Lands Institute.

Anne Trumble

The first armload of heavy “textbooks” I lugged out of my college bookstore included The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs. As a wide-eyed teenager on my own for the first time, the weight of choosing a course of study was also heavy. An instructor presented Jacobs’ observations of the social valuables on display in plain sight in Great Cities. Her methods were inspiring, and they provided comforting answers in a complex world. As I commenced a life in landscape architecture and urban design, Death and Life remained a guide, a gospel even, frequently referenced by colleagues, clients, and citizens.

I carried with me her courageous resistance to the powerful city gatekeepers she saw in opposition to the well-being of regular people, especially the marginalized and poor. I carried with me her exquisite observations of the nuances of everyday city life, and their widely adopted metrics for good and bad urban design. I declared an intention to visit her New York City’s Greenwich Village. It was painted with colors she argued did not exist in the dull, lifeless suburbs surrounding the farm where I grew up. She assured me that Boston’s North End was a suitable surrogate if I couldn’t make it to the urban pot of gold on the Hudson River.

As I began to think about the similarities between urban activist Jane Jacobs and political economist Elinor Ostrom, I realized that I had not read Death and Life since college. In the 20-years since, I lived in Jacobs’ Greenwich Village and tenaciously explored the nuances of New York City. I also encountered the ideas of Elinor Ostrom.

Ostrom’s Nobel Prize winning work on the commons in the governance of ecosystems is lesser known in landscape architecture and urban design circles. But it captured the attention of a team of geneticists I worked alongside in Madagascar. They were constructing critical habitat for the island’s endangered lemurs. Tavy, or slash and burn agriculture, and hunting lemurs as a food source, exemplified the tragedy of the commons. But the geneticists were developing their own system of reforestation, food security, and education, for mutual benefit of humans and lemurs. They were solving the commons problem locally and independently without state intervention, as Ostrom documented in cases across the world. In this context, her work explained what was happening in Madagascar. It also clearly demonstrated that understanding nature and culture as inseparable is critical to solving the commons problem.

Jane Jacobs solved a tragedy of the commons in her place and time by saving irreplaceable urban fabric and its social life from devastating urban renewal. However, Jacobs established a position in Death and Life that will limit the relevance of her work in contemporary urban socio-ecology. She described nature and culture as two separate entities that only overlap insofar as the former is an analogy for studying the latter. She explained: “By city ecology, I mean something different from, yet similar to, natural ecology, as students of wilderness address the subject”. She defined a natural ecosystem as “composed of physical, chemical, biological processes active within a space time unit of any magnitude,” and a city ecosystem as “composed of physical, economic, ethical processes active at a given time within a city and its close dependencies.” In conclusion, she stated: “The two sorts of ecosystems, one created by nature, the other by human beings, have fundamental principles in common. Cities are natural ecosystems for humans.”

Jacobs constructed many binaries throughout her writings: powerful versus poor, city versus suburb, credentialed versus un-credentialed, good design versus bad design, and foot people versus car people. But in separating nature from city ecosystems, her nature versus culture binary is perhaps the most limiting to the future of cities. As we enter a new geologic epoch, The Anthropocene, marked by the completion and permanence of human impact on the terrestrial biosphere, the cultural perception of a pristine nature separate from humans no longer exists. The future of all species, including our own, now sits entirely in our hands. Cities are more important than ever, as hybrids of culture and nature, if we wish to create landscapes that nurture all species in the new epoch.

Jane Jacobs, like Elinor Ostrom, was more interested in the dynamics of civilization than city planning itself. She revered the accretion of culture over time; how new kinds of work in vital societies evolve from old forms. If we can learn from and evolve both the successes and omissions of her ideas to solve present day challenges of the urban commons, I believe Jane Jacobs, the unceasing contrarian and independent thinker, would be pleased.

About the Writer:

Arjen Wals

Arjen Wals is a professor whose teaching and research focus on designing learning processes and learning spaces that enable people to contribute meaningfully to sustainability. A central question in his work is: how to create conditions that support (new) forms of learning which take full advantage of the diversity, creativity, and resourcefulness that is all around us?

Arjen Wals

Dialogical deconstruction for meaningful living within planetary boundaries: Ostrom’s and Jacob’s clues for addressing wicked sustainability issues

We have entered the Anthropocene: an era of human-caused global systemic dysfunction where human also will have a responsibility to disrupt and transform highly resilient but inherently unsustainable routines, lifestyles, and systems. A transition to, or, in some cases, a return to genius loci-based integral design of urban spaces that breathe sustainability, well-being and inclusiveness while recognizing cycles and planetary boundaries, is critical if “we” are to continue to live on the Earth.

How to live lightly, equitably, meaningfully and empathically (i.e., towards the past and the future, towards different cultures, the non-human and more-than-human world) on the Earth is the key question of our time. People across the globe are increasingly aware of and exposed to interrelated phenomena such as: climate change, loss of biodiversity, inequity- and natural disaster-related refugees, toxification of water, soils, air and bodies, and so on. Such issues, basically manifestations of the earlier referred to global systemic dysfunction, can be described as wicked in that they are inevitably ill-structured, ill-defined, inter-connected, highly contextual, complex, and drenched in ambiguity, controversy, and uncertainty. Does the work of Ostrom and Jacobs offer clues for learning our way out of persistent unsustainability?

Although they wrote in a different time and used different words, Elinor Ostrom and Jane Jacobs emphasize self-governance, autonomous thinking, and meaningful and playful interaction. So-called dialectical encounters in heterogeneous settings appear critical for addressing wicked problems and creating more sustainable communities (indeed they did not use the term ‘sustainable’). In today’s ‘transition movements’—sometimes related to energy, food, water, sometimes to a shared economy and solidarity, sometimes all in connection—we can identify these “principles”. Ostrom’s and Jacobs’ thinking has paved the way for a more relational and organic understanding of the world. The creation of a ‘sustainable’ community or urban area requires, along with a sense of place, identity and belonging, continuous dialogue between all involved to shape and re-shape ever changing situations and conditions. A dialogue here requires that the stakeholders involved can and want to participate as equals in an open communication process which invites diversity and conflict as a driving force for transformation.