The skin of the city shifts. Waves of residents come and go; meanings vanish. The longer I live here, the more I feel like I am a creature of many phantom limbs. Hungry, I walk to Jimmy’s hoping for fish and a chair to eat it in, but it is gone. In its place, a bodega expanded into a head shop and a pharmacy. It’s not the worst offense, these changing storefronts. But the churn at the whim of capital is a storm that rages and threatens the living parts of the City, the small human bits.

A century of disinvestment and municipal neglect add up to slow motion carpet-bombing. Buildings deteriorate until their removal seems inevitable, and whole communities are replaced with a “new” urbanism. Profit-driven construction, in the wake of orchestrated disinvestment and a legacy of public and private neglect, transforms New York City; neighborhoods once full of social clubs, artists’ spaces, churches, and dances halls become rows of shells for private luxury living. These “investments” leave an eerie emptiness in their wake; there are simply fewer people in the new neighborhoods.

In January 2013, the organization I run, 596 Acres, became one of the first “stewdio” tenants at the then-newly-reopened Silent Barn in Bushwick, Brooklyn, an artist-created-and-run cooperative space. 596 Acres took over a portion of a former car mechanic’s garage, broom-swept, oil stains still on the floor. The Silent Barn had signed a 10-year lease on a live-work space that suggested some kind of permanence, or at least some kind of duration. 2022 seemed an awfully long time away.

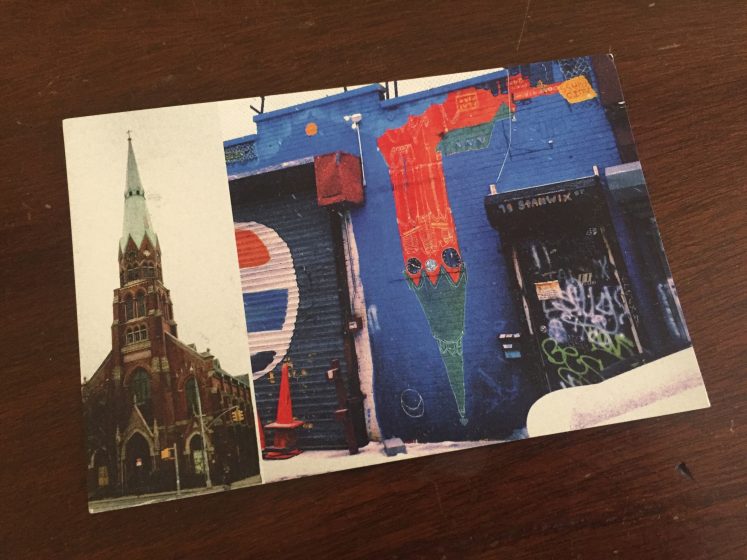

Around the corner from our new “office” stood a majestic church with a 190-foot copper steeple, St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, opened in 1892. The building had hosted a congregation for over a century, and a community garden for several decades, and in the more recent past had become the site of parties, artist studios, and, briefly, an indoor velodrome for bicycle races.

The steeple was how everyone told direction in that corner of Brooklyn; it reached dozens of feet above the elevated subway tracks and winked its ever-greener green. A few blocks in each direction, three distinct street grids turn away from each other, relics of the independence of the six towns that became Kings County in New York State and then the City of Brooklyn, which later became one of the five boroughs of New York City. A compass marker here has helped orient residents for over a century.

But the church and its spire have never been formally designated a “landmark,” despite numerous requests for the NYC Landmarks Commission to evaluate the building for a designation under the NYC Landmarks law. These include one made to the local City Council Member and a team of Architecture History students from Columbia University in 2010, but all were ignored by the agency or cast aside with the simple response that the building itself was in too precarious a condition to designate.

Rapacious development was already churning and devouring New York City’s outer borough neighborhoods. Gathering places are first on the chopping block.

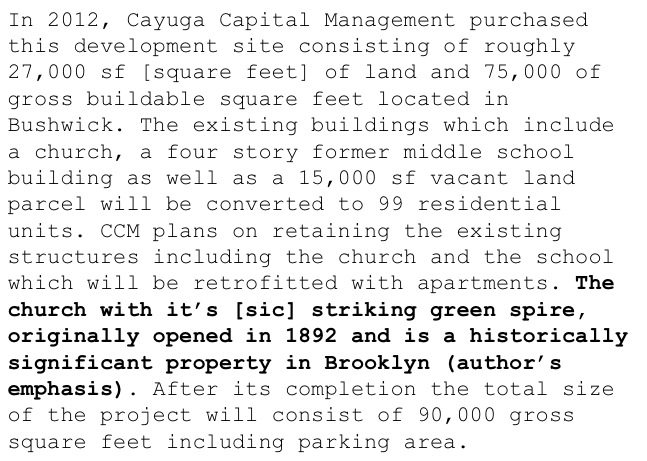

The week we moved to the Silent Barn, the sale of the former church building across the street to Cayuga Capital Management, a private for-profit developer planning a market-rate condo conversion, had just been completed. Architects seeking approval of their plans showed drawings that left the pointy spire intact and described apartments with stained glass windows in its upper reaches. The developers, in their marketing materials, wrote:

The whole thing was becoming 99 expensive rental apartments.

The Church was designed by Cooper Union-educated architect Theobald Engelhardt a generation after the village of Bushwick was incorporated into the new City (!) of Brooklyn. Mr. Engelhardt located his own architecture office around the corner from the Church site on Broadway while the spire went up. It was in a building he also designed on what was then Brooklyn’s Wall Street, across the street from a German singing society hall the construction of which was paid for by its members, and which he also designed.

One hundred years later, the intricate architecture—created to foster social inclusion, artistic production, and a life of collective endeavor—is rapidly transforming into private residences rented and sold for ever-higher prices on the unregulated market. The singing hall is now the Opera House Lofts and many private developers are buying up churches and converting them to residences for those who can afford their lofty ceilings and bespoke window frames.

Formal NYC Landmark designation is primarily reserved for architectural artifacts, disconnected from their cultural context or their social import. A landmark designation for a piece of the built environment, with its mercurial meanings bestowed by changing local demographics over many decades, is extremely unlikely, though in 2015, in an unprecedented move, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designated Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village.

That Commission report begins, “The Stonewall Inn, the starting point of the Stonewall Rebellion, is one of the most important sites associated with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender history in New York City and the nation.” It continues for many pages, describing how the Stonewall Inn operated (“the owners made regular payoffs to the Greenwich Village’s Sixth Police Precinct”) and contextualizing the role of this meeting place in its historic moment (“New York police could arrest anyone wearing less than three items of clothing that were deemed ‘appropriate’ to their sex, and the State Liquor Authority made it illegal for a bar to serve someone who was known to be gay.”). As the New York Times reported, several speakers at the designation hearing pointed out that the buildings that house Stonewall are not architecturally distinguished and “would not earn landmark status on aesthetic grounds.” Yet the designation will protect the physical buildings that house the Inn from future alterations.

This may be a new path to protecting places that matter to our communities for their mattering, but it’s coming late, after one hundred years of redlining, the cut-backs in municipal services of the 1970s and 1980s, “urban renewal,” blight designations and bulldozers. The economic history of our city’s neighborhoods has ripened many for replacement, has forced families and communities to move away from places they loved because the disinvestment turned septic, turned into danger and reduced life expectancies. People who could took their children away to live in more orderly and invested places, stopped attending church, stopped paying fees to the singing club, eventually stopped coming back when their neighbors did the same.

In 2013, I knew that the architects’ promotional materials were just advertising and nothing in their renderings was enforceable.

Predicting then that the church would not survive its conversion in any cognizable form, Daniel Eizirik, an artist in residence at 596 Acres, and I conceived of a mural: If You Love the Music, Spare the Drummer (a cumbia for Stanwix Street). In it, Daniel captured the world we saw that upside down winter, a tiny corner of a larger world that we knew was vanishing, a tattoo on brick inked to mark a moment.

In it are the fish place, a Spanish-speaking fashion boutique, chain link fences surrounding city-owned land, a flat fix/auto glass joint attached to the gas station. The map is not the territory, and the portrait is not the person, but in some places, under seismic shifts in demographics and geographics, the map and the portrait are our last fixed points.

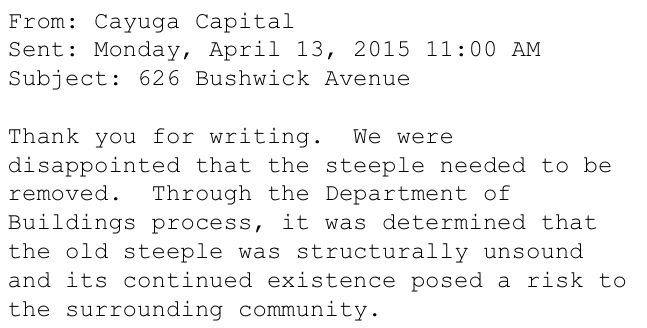

I won’t call it graffiti, this practice of making memory by inscribing place onto itself. Our memorial, like the Landmarks Commission’s designation of Stonewall, is not based on architectural distinction, though the building was certainly distinguished; it is the only landmark designation that Mr. Engelhardt’s majestic spire will ever get. The painted version has already outlasted the 190-foot cooper one, which was placed into a dumpster and sold for scrap over the winter. The apartments are nearly ready, and the spire itself has been capped, an echo of itself and of Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche, another nineteenth-century German church with its steeple now lopped off, a memorial to forces of this century and their transformation of urban centers.

Paula Segal and Daniel Eizirik

Brooklyn and Porto Allegre, Brasil

about the writer

Daniel Eizirik

Daniel is an artist living in Brasil. He has collaborated with 596 Acres on several projects that have included telling the stories of places.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation