By all rights a one-eyed bald eagle is a doomed bird. Imagine trying to catch a salmon or a brush rabbit with no depth perception. Oh eagles will scavenge and occasionally steal food from one another, but roadkill and kleptoparasitism will only get you so far in life…or so the conventional wisdom goes. The one-eyed eagle that finds its way into captivity should be put out of its misery or relegated to life in a zoo. To release such a bird is to condemn it to a slow death by starvation.

Late on a Saturday afternoon in early November, shortly before Sunset, Portland Audubon’s wildlife hospital received a call about an injured bald eagle on West Hayden Island. The location was notable. West Hayden Island sits at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. Lewis and Clark camped here almost exactly 208 years to the day earlier on their journey to the Pacific. They called it “Image Canoe Island” after observing a Native American canoe carved with the images of men and animals emerging from behind the island. It was a place teaming with wildlife. Captain William Clark noted in his journal the following:

Rained all the after part of last night, rain continues this morning. I [s]lept but verry little last night for the noise. Kept [up] during the whole of the night by the Swans, Geese, white & Grey Brant, Ducks, etc on a Small Sand Island close under Lard. Side; they were emensely numerous, and their noise horid [sic].

Two centuries later, West Hayden Island represents one of the last intact remnants of this once fertile delta area. Its 800 acres of bottomland forest, wetlands and meadows, sit between the cities of Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington. The surrounding river has been deepened, straightened and its banks hardened to make way for industrial development. Marine terminals line the banks to the north and south. East Hayden Island has been fully developed — nearly 750 acres of shopping malls, auto lots, high end condos and Oregon’s largest manufactured home community.

What little natural area that remains is an oasis for federally listed migrating salmon that require shallow water habitat to rest, forage and temporarily escape larger predators on their journey to the ocean. Its uplands provide habitat for a plethora of wildlife. Almost the entirety of West Hayden Island lies within the 100-year floodplain and during major flood events much of the island can be almost entirely submerged.

It is also a battleground. For nearly two decades the Port of Portland and other industrial interests have fought to turn West Hayden Island into marine industrial terminal. Even as other downriver port facilities sit vacant awaiting tenants and teetering on the brink of failure, development interests in Portland argue that this is the last big parcel available for marine terminal facility development in Portland.

There are no tenants lining-up for West Hayden Island either; the Port can’t say what it will build or when it will be needed. A decade ago they thought it would be containers. Today the best bet is auto imports. It doesn’t matter. The important thing is to be ready future whenever it comes and that means annexing the island, rezoning it for development, filling its floodplains and waiting for the “next big thing” in the realm of imports or exports.

On the other side of the issue, a loose coalition of environmental groups, neighborhoods and tribes have a different conception of what it means to be “prepared for the future.” Representatives of the Yakama Nation travel more than 100 miles downriver to testify against this development at hearings. In a letter dated November 6, 2012 they wrote:

What was true in 1905 — and for thousands of years before that — is still the case today and will be for the Yakama children yet unborn; salmon and the health of the Columbia River are of paramount importance to our people.

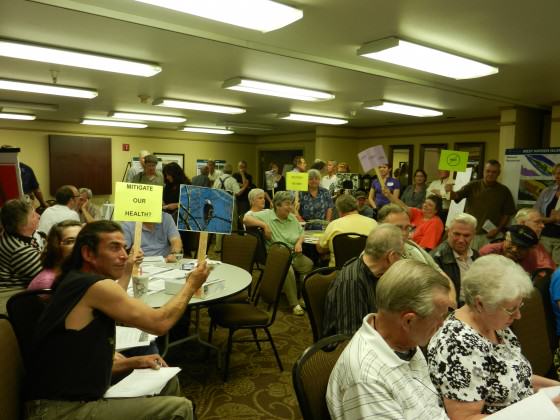

They are joined in their opposition by a manufactured home community — a trailer park in more common lingo — that has persisted more than 40 years adjacent to the natural area…high end real estate that somehow has managed to remain low income housing for more than 2000 people. In 2012, the City of Portland adopted a long range vision known as the Portland Plan which established equity as the city’s “core principle.” Hearing this, the locals rose up and flooded hearings demanding equity, although one self-described “grandma” admitted to me afterwards that she didn’t actually know what the term meant.

That’s okay, the city and port don’t really know either. It is a work in progress. From the Port’s perspective, equity equals jobs and a larger tax base. Our development community likes to talk about a three legged stool of economics, environment and equity. Funny thing about that stool though. Too often the economic leg is growing while the equity and environment legs are getting shorter. One should think twice before sitting on that stool.

In this case a small army of sign-waving “grandmas and grandpas” demanded something more substantive than metaphors, a Health Impact Assessment, defined by the Centers for Disease Control as “a process that helps evaluate the potential health impacts of a plan, project or policy before it is built or implemented.” The City agreed to do a truncated version called a “Health Analysis” — sort of a Health Impact Assessment “Lite”. The findings were not pretty. The final report revealed that, even with mitigation strategies in place, the proposed development would potentially triple air toxic levels to 55 times the state benchmarks in the local community. It also described the potential for development induced poverty and displacement in the local community.

In fact the project has generated a small mountain of reports. The project website lists more than eighty such documents: Economic Foundation Studies, Cost/ Benefit Analyses, Mitigation Plans, Market Studies, Growth Concepts, a report on the viability of the black cottonwood forest, another on the value of floodplains…this list goes on. The goal is to find “balance.”

If we study it long enough and hard enough perhaps a win-win solution will materialize. It hasn’t. Some places are special. They shouldn’t be turned into parking lots.

Which brings me back to the one-eyed eagle. As the sun was sinking low in the sky, my eleven year old son and I drove through the tangle of sprawling development that now covers East Hayden Island, past the shopping mall and the convenience stores and the impossible to ignore and even harder to explain “Hooters” sign, past the auto auction lot and single story industrial office parks, and finally past the tidy manufactured home community. We met the hiker who had reported the injured eagle and together we headed out into the wilds of West Hayden Island.

We found her perched in a meadow a little over a mile from the gate, a big female, white head stark against the falling darkness. When I approached she leapt into the sky, but only one wing extended and she twisted awkwardly and dropped back to the ground. We quickly bundled her up in an old Mexican blanket I had brought with me and began the mile long trek back to the car. I wondered as we walked whether this eagle could be the eagle that a few years back had established a nest and began raising young in the middle of the proposed development area. We often featured that eagle in our efforts to protect West Hayden Island. Her picture adorns the banner atop our “Save West Hayden Island” Facebook page.

Our veterinarian met us at Audubon later that night and we gave her a full work up. In addition to the injury to her wing, she had fresh wounds on both of her legs. Most likely she was injured in a territorial dispute with another eagle — the most common cause of injury for eagles treated at our center. X-rays revealed that at some point in her life she had also been shot. A bb was still lodged deep in her breast muscle but by all appearances, it had been there for quite some time.

However the worst thing was the right eye. I couldn’t see it when we were carrying her through the darkness on West Hayden Island, but we all saw it right away as we unwrapped her from the blanket under the surgical lights of our treatment room. The right eye was badly damaged — beyond repair. As we worked to treat her injured wing and legs we knew in the back of our minds that she was most likely never going to return to the wild. It was sad. She was a beautiful bird, nearly 12 pounds, other than her injuries in perfect body and feather condition. We consulted other experts from around the country. They all said the same thing. She wouldn’t survive in the wild with one eye.

However sometimes conventional wisdom is wrong. A veterinary ophthalmologist surprised us a few days later when she confirmed that indeed the damage to the eye was severe, but also that it was old, many months old, perhaps years. This bird had most likely been surviving in the wild for quite some time and doing quite well despite the injured eye.

Verification of her strange and unlikely journey came from an even more unlikely source. David Redthunder lives in the manufactured home community on Hayden Island. He spends much of his time communing with the wildlife that inhabits West Hayden Island. He has an uncanny ability to get close to the critters and he has a particular affinity for the nesting eagles. Sometimes when I visit the island, I find small shrines he has built to protect the birds.

Over the years he has sent me hundreds of amazing photographs he has taken of the island’s wild inhabitants including dozens of the eagles. (To see a gallery of David’s West Hayden Island Photos go here.) What were the odds that David would have captured an image of the injured eye? It seemed like a fool’s errand, but I opened the file of David’s photos on my computer and began scanning. About 30 photos along, I found it….a blurry photo dated August 12, 2012, the injury to the right eye clearly visible. The injury was more than a year old. She had not only survived her eye injury, but also apparently has successfully nested and raised two young.

More of David Redthunder’s West Hayden Island wildlife photos follow. To see more, go here.

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

A one-eyed eagle is still a long shot. Not every bird survives. Not every story has a happy ending … but if she can fly, let her go. Let her have her freedom.

Bob Sallinger

Portland

.

What a pleasure it was to read this article and the weaving of a tale of survival over the arching demands that humanity places on eco-systems. Hopeful this island will never be devloped and we has humans can find more regenerative methods of development that can help heal native places so that we can exisit in harmony with our surroundings.