I have long been a believer in E.O. Wilson’s idea of biophilia; that we are hard-wired from evolution to need and want contact with nature. To have a healthy life, emotionally and physically, requires this contact. The empirical evidence of this is overwhelming: exposure to nature lowers our blood pressure, lowers stress and alters mood in positive ways, enhances cognitive functioning, and in many ways makes us happy. Exposure to nature is one of the key foundations of a meaningful life.

How much exposure to nature and outdoor natural environments is necessary, though, to ensure healthy child development and a healthy adult life? We don’t know for sure but it might be that we need to start examining what is necessary. Are there such things as minimum daily requirements of nature? And what do we make of the different ways we experience nature and the different types of nature that we experience? Is there a good way to begin to think about this>

A Powerful Idea

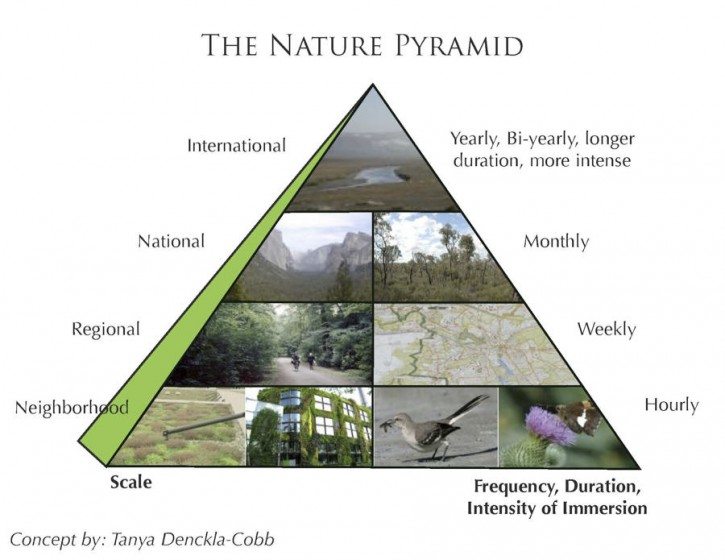

Here at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA USA), my colleague Tanya Denckla-Cobb has had a marvelous and indeed brilliant idea. Why not employ a metaphor and tool similar to the nutrition pyramid that has for many years been touted by health professionals and nutritionists as a useful guide for the types and quantity of food we need to eat to be healthy. Call it, as Tanya does, the Nature Pyramid, and we have something at once novel and attention-getting, but potentially very useful in helping to shape discussion about biophilic design and planning. Towards the top end of that nutritional pyramid, as we know, are things that, while important to overall nutrition—meat, dairy sugar, salt—are less healthful in larger quantities and should be consumed in the smallest proportions. Moving down the pyramid are elements in the diet—fruits and vegetables—that should be consumed more frequently and in greater quantity, and then finally, grains that provide healthy nutrients and carbohydrates that are needed on a daily basis. The Nature Pyramid would work in a similar way. I have taken a stab at what the nature pyramid might look like, presented in the graphic below. It is a bit different than Tanya’s initial idea, but a version I am convinced will be highly useful as a way to begin to explore and discuss the amounts and types of natural experiences we need to live a healthy life.

The Nature Pyramid, then, challenges us to think about what the analogous quantities of nature are, and the types of nature exposures and experiences, needed to bring about a healthy life. Exposure to nature, direct personal contact with natural is not an optional thing, but rather is a necessary and important element of a healthy human life. So, like the nutritional pyramid, what specifically is required of us? What amounts of nature, different nature experiences, and exposure to different sorts of nature, together constitute a healthy existence? While we may lack the same degree of scientific certainly or confidence about the mix of requisite nature experiences necessary to ensure a healthy life (or healthy childhood), as exists with respect to dietary and nutrition (and of course there remains much disagreement even about this), the pyramid at least begins to ask the right questions. It starts an essential and important conversation that needs to occur given our modern earthly circumstances.

The Nature Pyramid helps us to begin to think about what will be necessary to counter what journalist Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder” in his important book Last Child in the Woods (Algonquin, 2005; and further explored in his more recent book The Nature Principle, Algonquin, 2012). It is helpful for several reasons. First and foremost perhaps is the important message that, like one’s diet, it is possible to act in ways that lead to a healthy mix and exposure to nature. This is subject to agency and behavior and responsible choice in the same way that the food pyramid guides eating. And, like the nutritional pyramid, the Nature Pyramid provides guidance to planners, designers and public decision makers. We have important choices about community design: what we choose or choose not to subsidize, what nature opportunities we want our children and adults to have available to them, and what steps might make a healthier biophilic life more feasible or possible.

What Should Make Up the Bulk of Our Nature Diet?

At the bottom of the pyramid are forms of nature and outside life that should form the bulk of our daily experiences. Here there are the many ways in which we might daily enjoy and experience nature, both suburban and urban. As adults, a healthy nature diet requires being outside at least part of each day, walking, strolling, sitting, though it need not be in a remote and untouched national park or otherwise more pristine natural environment. Brief experiences and brief episodes of respite and connection are valuable to be sure: watching birds, hearing the outside sounds of life, and feeling the sun or breeze on one’s arms are important natural experiences, though perhaps brief and fleeting. Some of these experiences are visual and we know that even views of nature from office or home windows provides value. For school aged kids spending the day in a school drenched in full spectrum nature daylight is important and we know the evidence is compelling about the emotional and pedagogical value of this. Every day kids should spend some time outside, sometime playing and running outside, in direct contact with nature, weather, and the elements.

Moving from the bottom to the top of the pyramid also corresponds to an important temporal dimension. We need and should want to visit larger more remote parks and natural areas, but for most of us the majority of these larger parks will not be within distance of a daily trip. At the top of the pyramid are places and nature experiences that are profoundly important and enriching, yet are more likely to happen less frequently, perhaps only several times a year. They are places of nature where immersion is possible, and where the intensity and duration of the nature experience are likely to be greater. And in between these temporal poles (from daily to yearly) lie many of the nature opportunities and experiences that happen often on weekends or holidays or every few weeks, and perhaps without the degree of regularity that daily neighborhood nature experiences provide.

Like the food items higher on the food pyramid, the sites of nature highest on the Nature Pyramid might best be thought of occasional treats in our nature diet—good for us in small and measured servings, but actually unhealthy if consumed too often or in too great a quantity. For many urbanites from the industrialized North, large amounts of money and effort are expended visiting remote eco-spots, from Patagonia, to the cloud forests of Costa Rica, to the Himalayas. It seems we relish and celebrate the ecologically remote and exotic. While they are deeply enjoyable nature experiences, to be sure, they come at a high planetary cost, as the energy and carbon footprint associated with jetting to these places is large indeed. No longer are such trips appreciated as unique and special “trips of a lifetime,” but fairly common and increasingly pedestrian jaunts to the affluent citizenry of the North. The Nature Pyramid sends a useful signal that travel to faraway nature may as glutinous and unhealthy as eating at the top of the food pyramid.

Another message is that a diversity of nature experiences will yield a healthy life, in the same way that a diversity of foods and food groups leads to a healthy diet. The middle of the pyramid suggests the need for larger local and regional green spaces that provide more respite and deeper engagement than street trees or green rooftops might. They can be visited less frequently, but perhaps with greater duration and intensity, say on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. The Nature Pyramid allows us to imagine lives lived mostly in urban (albeit green urban) environments but with some substantial amount of time spent in more classically natural environments around and outside cities. The pyramid lets us begin to imagine—as we imagine the combinations of food and types of food that go into our daily and weekly diets—the combination of different nature experiences essential to a healthy human life.

Overcoming the Nature-Urban Dichotomy

The Nature Pyramid encourages us to overcome the paralysis of the modern urban-nature split that many of us perceive. For example, the United States is an urban population, for the most part: more than 80% of Americans live in metropolitan areas. Cities and urbanized areas typically provide less direct contact with the kind of pristine nature we often think we need. There are good and important reasons we live in cities, and from the perspective of sustainability and sustainable living, cities are an essential aspect of effectively addressing global environmental problems. Yet, the types of nature found in cities are more fragmented, smaller and generally allow less and shorter kinds of immersion than, say, camping in a remote wilderness area or spending several days in a national park. But as the planet continues to become more urban the challenge of providing the essential minimum dosage of nature becomes an increasingly important challenge everywhere.

Many of the techniques currently used to green urban environments provide value—”nature nutrients” if you will—in the lower rungs of the pyramid. Green design features such as eco-rooftops, bioswales and rain gardens, community gardens, trees and tree-lined streets, and vegetation strips and urban landscaping, provide valuable ecological services (from retaining stormwater, to moderating the urban heat island problem, to sequestering carbon), but they also provide urban residents with exposure to nature, albeit in a human-altered context. The pyramid helps us see how the daily consumption of and exposure to the myriad green features of cities provide, like a balanced food diet, a healthy mix of nature experiences. I know in my own case I notice and enjoy the circling turkey vulture, the ant life and invertebrate antics below foot, the sounds and sights of the not insignificant green strips and edges that I walk by on my way to work and on walks through my neighborhood. I might be happier (and healthier?) if my nature experiences were deeper in time or quality, but these fleeting and fragmentary episodes of a green urban life are valuable and indeed make up the bulk of my daily nature experiences. The Pyramid helps us appreciate the valuable exposure to many smaller green features and nature episodes in the course of a day, and importantly, the need to include these features in urban design.

Thinking About “Servings” and “Nutrients”

There are many unknowns in this conceptual framework, of course, and many open questions. But the Nature Pyramid is valuable in identifying and framing these important questions. One interesting question is how we measure the “servings,” if you will, of nature exposure in this nature diet. What is the unit of measurement that we ought to speak of in terms of a nature experience; say a walk or other time outside that takes twenty minutes or a half an hour, or something qualitatively different, say a momentary sighting of a bird, or tree, or distinctive mushroom. Is a ten-second glance out the window at work onto a verdant courtyard adequate to compose a “serving”? Is the momentary wonder at the interaction of two birds, at the joyous sight of a circling hawk, the scolding chatter of a squirrel as you pass by that corner lot with the large trees a useful serving? And how, over the course of an hour, an afternoon, a day, do these servings add-up to or accumulate to form the nature nutrition we need?

Often our nature “servings” don’t nicely fit into any description of an event or episode, and are more continuous, less discrete: for instance the aural background of natural sounds, the katydids, tree frogs, crickets that compose the night soundscape that many of us find so replenishing and soothing. One’s day is, in fact, made up of unique and complex combinations of these nature experiences (or they should be), some fleeting and momentary, others of longer duration and intensity. The Nature Pyramid helps us, at least calls upon us, to develop some form of metric for understanding this richness and complexity and to understand how (or not) these different experiences add up over the course of a day, week, month or year to a healthy life in close and nurturing contact with the natural world.

And there are other important open questions highlighted by the Nature Pyramid. Is it possible to imagine more intensive, immersive nature experiences even in normal everyday urban environments; urban places and smaller urban environments that may deliver the restorative power of experiences higher on the pyramid? And can we design them in ways that intensify these experiences? A brief visit to a forested urban park, or botanic garden, could in theory permit an immersive experience equal to more distant forms of nature. Again, these are important questions that the framework of the Nature Pyramid helps us to identify and focus on.

The Nature Pyramid encourages us to look around at the actual communities and places where we live to see if they are delivering the nature nutrients and diet we need. Yale professor Stephen Kellert argues that we need to overcome the sense that nature is “out there, somewhere else,” probably a national park, and what we need today more than ever is “everyday nature,” the nature all around us in cities and suburbs. Much is there, of course, if we look, but we must also work to enhance, repair and creatively insert new elements of nature wherever we can, from sidewalks to courtyards, from alleyways to rooftops, from balconies to skygardens. Less frequent perhaps are the deeper and longer episodes—the visit to a regional park, the longer hike along a nature trail or through a regional trail or greenway system beyond one’s immediate neighborhood. These experiences might for some happen daily, but likely don’t. They are more infrequent, tending to occur more on a weekly than daily basis. There are several nature trails my family visits and hikes on weekends, and they form a part of our healthy nature diet.

We can quibble, certainly, about what the appropriate mix of nature experiences is or ought to be, to ensure health and well-being—how much of our day should be about experiencing nature through an outdoor walk on a trail or in a park, versus contemplating a beautiful view of a river or forest from an indoor room or balcony? But the pyramid most importantly helps us to see that for most individuals, living a healthy urban life in touch with nature is a function of the daily, weekly, and monthly (and even less frequent) nature experiences we have. Ensuring that we provide the minimum dosage or serving of nature should be a priority for all planners and designers.

A Rich Research Agenda

While the Nature Pyramid already provides us with important policy and planning insights and guidance, there are clearly many important open questions and a significant (and exciting) research agenda that flows directly from it. Addressing these questions will require the good work of researchers in a number of disciplines, including medicine and public health, psychology, and of course the design disciplines of landscape architecture and city planning, among many others. The research questions are not easy ones, as this essay has shown, but are in fact rather complex. There is a need to focus at once on the natural elements and processes of neighborhood urban nature (trees, birds, gardens), the different ways in which these elements are experienced or enjoyed (listening, seeing, digging in soil), and the many factors that may influence their emotional import and “nutritional value” (are they experienced alone or enjoyed with others, with friends and family, for example). And there is a need to better understand and describe more precisely the outcomes or benefits delivered, i.e. the ways in which exposure to nature makes us happier and healthier.

And there are complex behavioral cascades that will need to be better understood. If we feel happier when we see trees and vegetation in our neighborhoods, for instance, we are more inclined to spend time outside and engaged in walking, strolling, hiking and other physical activity, in turn delivering important physical health benefits. Some studies already confirm this. Equally true, trees and nature create context for socializing, thus in turn delivering important emotional benefits (and we already have considerable evidence about the many health benefits of friendships). So the research task becomes one of better understanding how and in what ways the nature in cities can set in motion other positive health outcomes (and again, which natural elements, experiences, features, or processes, and in which combinations, will trigger these valuable cascades).

Some of this research is already underway through our Biophilic Cities Project, here at the University of Virginia, with funding from the Summit Foundation and the George Mitchell Foundation. Much of our work has focused on learning from emerging biophilic cities around the world, and the tools, techniques and ideas these exemplary cities are employing to deliver nature to their citizens, and to foster connections and contact with the nature. We have partnered with some exemplars of urban nature, including Singapore, Portland, San Francisco, and Oslo, among others. But soon we will also be attempting to tackle the question of the minimum daily dose of the natural world. We are planning to consult leading researchers in medicine, public health, and other fields about the question of minimum levels of nature, through the use of a Delphi process, and to explore whether there might emerge some areas of early consensus about what kinds and amounts of nature urbanites need.

We are also beginning to work with our colleagues in psychology to better understand the comparative emotional and restorative value of different combinations of urban nature. But this work is just a beginning, and we will need many colleagues, in many allied disciplines, to join with us in this important work. While we know much, there is so much more to do, and so much exciting research to at least begin in the next few years. The Nature Pyramid, rather than being an answer or a complete and fully-developed model, is but the beginning point, a provocation to explore and innovate and better understand the important ways in which everyday, neighborhood nature can help deliver the essentials of a happy, healthy and meaningful urban life.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville, VA

USA

Spectacular concept! Passing this site on to the Merced Environmental Literacy Collective (MELC) partners!

Some of us living in deeply rural areas are tending the nature that surrounds us. Isn’t this a basic role of the human-being, to tend and steward? I know deeply that we are. Few these days are likely to have the knowledge, experience and wisdom it takes to be such “tenders”. Those of us who do are in a situation/position to teach others who can and will. I do.

“I have only two neighbors on my dirt road of several miles.”

This sort of ‘rural’ seems extremely unsustainable except possibly for families living off the land, which is maybe what you are doing, but which could support very few. Sustainable * rural * should mean rural villages, not private, remote ‘homesteads’. So the word ‘neighborhood’ could be replaced by ‘village’ for rural areas.

When we lived in the centre of Paris I classed it a ‘good day’ if I saw eagles circling above the Champs de Mars. Even if I was stuck indoors writing for the rest of the day, if I’d seen the eagles soaring majestically, I felt uplifted and inspired.

I agree, it is the juxtapoistion of the built environment and the beauty of nature that makes the nature experience more profound. If we have one profound experience is that better for us than many lesser nature encounters? How that thought then fits into the pyramid model I’m not sure. Perhaps, as someone suggested, a concentric ring model may work. I’ll have a play with the idea and see.

Gayle Souter-Brown

Director, Greenstone Design

Wellington, New Zealand and London, England

Thanks. This asks questions that need to be answered as we move towards quantifying what a necessary ‘dose’of Nature might look like, and how it might differ for different people, just as medical (chemical) prescriptions are altered on the basis of age, weight, ethnicity

Tanya, you put that well – rural people can and do suffer a disconnect, and it is ironic given their location. But how to describe? Distances and scale in rural areas tend to be larger. In New Zealand the term ‘district’ is used to denote things that happen in a neighbouring part of our particular rural area

Dr. Beatley I found this blog entry to be quite intriguing. The concept of taking nature and subdividing it into categories so that people can effectively see the amount of nature that they dont get in their lives is excellent. I have to wonder, though, if trying to take the nature categories, and make them fit the mold of the food pyramid is not like trying to fit a square block into a round hole. Nutrition is somewhat one dimensional. Nature “consumption”, however, seems to be much more complicated.

For example, the nature that you experience walking down a sidewalk, can also be experienced in a park. The experience in that park could also be found in a much larger park, so each larger step would embody the one before it so it would seem to make more of a spherical shape. Understandably, the opportunity and environmental cost to visit these more remote places does take its toll, but that is not to say that these remote places are less valuable, which may be the idea the general public may conceive if they see pristine wilderness at the top of the pyramid.

I think that with incorporating nature into our human habitats, it is important to remember that we ourselves are apart of nature and it is there for us to use and we are here to give back to it. I dont think it is completely necessary to coat everything with trees and shrubs to make it appear to be more nature, but to only take what we need to use. One person does not need 2,500 square feet to live. A bird does not build a nest big enough for ten birds its size and live there alone. If we are able to minimize the amount of space, not to an uncomfortable level, that we use in designing buildings, homes, and other real-estate, more parks and green spaces would be available to the public, and in a much shorter distance.

The studies of the psychology colleagues showing how nature effects human emotions would be very interesting. A study showing why people have an urge to, at the same time of wanting to enjoy nature, keep it separate from their own personal space, would also be enlightening.

Thank you again for such a wonderful article!

Brandon Bourque, Student-SO

Auburn University

City Planning

Auburn, Al

This is an interesting comment from Michael A. Hill that appeared at the Sustainable Cities Collective’s site, where TNOC posts are streamed.

You can view and reply to the original comment here: http://sustainablecitiescollective.com/nature-cities/55286/exploring-nature-pyramid#comment-10576

Here’s the comment:

An important difference between the nature pyramid and the food pyramid is the agreed-upon outcome — in the food pyramid, we have well-defined outcomes regarding physical health that we want to get for kids. We know that the items in the pyramid are going to be consumed, and that the proportions will lead to a balanced diet. We also have general agreement on what defines a healthy person.

The nature pyramid is different because the health outcomes are indirect, and many of the outcomes are attitudinal or psychological in nature. Generally, it is hard to evaluate behavior change without studying people over a long timeframe. This allows linking experiences to changes in behaviour and attitude. There are a few challenges with the arguement as set out.

First, we don’t clearly state what the desired outcome is — what does a kid who gets his daily dose of nature act like. I’m focusing on action because to set any physical standards you would need to control for a vast number of environmental and hereditary variables that are beyond our ability to even fully catalog. If we can all agree that the environment is a “common good” in the public realm, we can link it to bigger ideas about how we want responsible citizens to behave generally. Right now, people in the environmental movement are sticking every possible positive outcome to the nature deficit reduction movement with very little data — that means we are setting ourselves up to have many of these claims debunked, and casting the entire effort in doubt.

So thinking simply, what does a good environmental citizen act like? Does she understand natural processes and environmental impacts of her decisions? Does she see herself as part of the natural world, or separate from it? Does she think a natural setting is inevitably ruined by human action, or that people can improve nature through our actions? Does she have every-day responsible environmental behaviors? Does she see our natural resources as something we steward for future generations? Does she even understand what stewardship is? Does she pass on these ideas to others, by word and deed? Does she consider the environment when she’s buying a car, choosing a house, or voting for mayor? I’m sure this is a partial list, but I like it because the kid who camps every weekend of the summer and the kid who can’t spend a lot of time outside — because of allergies, or because her family can’t afford to go camping — can come up equal on this scale.

The other problems have to do with the implications of the pyramid graphic. Any kid looking at a pyramid (and a lot of adults) have a simple bias in their mind — the good stuff is at the top. Wiith the nature pyramid as currently defined, there’s the problem of feeding into other long-standing biases. These biases go all the way back to Teddy Roosevelt, Frederick Law Olmsted, Arthur Carhart and the contingent of white male outdoorsmen who started both the urban parks and national parks movement at the turn of the 20th century. They built their efforts on edenic ideas about “Big ‘N’ Nature” and these assumptions preference the dominant culture’s view of what nature is and isn’t, and sets up “Big ‘N’ Nature” experiences as a the gold standard. It doesn’t recognize that for people from different backgrounds, getting to someplace like Yosemite might not only be unrealistic, it might be not be fun, nor the best way to build the good environmental citizen we described above.

Imagine for a moment that you are a kid that spends every weekend with his grandmother in a small community garden in the Bronx (or Detroit, or Oakland, etc.) working in a small plot. You’re hanging out, listing to old people tell funny stories, learning recipes for all the stuff your growing, hearing about how this garden compares to the one gramma had in the old country, meeting your neighbors and learning to respect their gardening expertise. And these lessons are going to stick, because they have two key things that make information stick in anyone’s head — they are repeated in many different ways over and over again; they are intimately connected to your sense of self and place; and you get praised for learning them by people whose opinion matters to you.

Now imagine that same kid taking part in a camp program where he goes once a week to a woods that he doesn’t own, isn;t near his community and doesn’t impact his life in any noticable way; learning environmental lessons that he doesn’t have the time or ability to really implement and see outcomes; working with people who he is only developing a connection with; and there’s very little coming out of this version of nature that he can use in a concrete way in his day-to-day life — assuming we can all agree that a lanyard woven from plastic string is less useful that a bushel of vegetables.

Which set of experiences is most important to build a life-long stewardship ethic? And does the diagram put the most important experiences in the most important place?

Don’t get me wrong, I love the big parks. I realize that those spaces provide ecosystem services of real value to our economy and national security. I also understand that, as our population gets more urban, we need to teach people about these places so that they act to protect them. I just think that we need to consider that the most special natural place is one that’s most meaningful to the individual, and that diverse audiences will have different ideas about what a citizen steward acts like, and what experiences in what proportion will build her. Any diagram we use to talk about something this important needs to speak to everyone’s experiences.

I’m coming to the “Nature Pyramid” discussion late. . . but clearly better late than never! Like other commenters, I find the Nature Pyramid idea (and Tim’s posting) provocative and fascinating. The question of “what’s a healthy diet” of interactions with the larger world of nature is a great one (though as Tim points out, not an easy one to answer). In my own life of nature writer, I’m fortunate enough to get an regular — and substantial — “serving” of nature on my almost daily outings right here in Anchorage, Alaska’s urban center. And yes, there are the less frequent but richly rewarding experiences in the nearby Chugach Mountains and other, more remote, wilderness areas. What is a person’s daily minimum requirement of nature for a healthy, meaningful, fulfilling life? Hard to say, but I think it’s important to ask such questions. Great food for thoughts, thanks.

I really LOVE how you’ve shaped the idea of the Nature Pyramid, Tim!

The original idea was inspired by Louv’s nature-deficit disorder in children, and so I focussed exclusively on visually conceptualizing guidelines for parents in managing their children’s schedules. Or, rather, my hope was to build on Louv’s lessons to prioritize parental goals for their children, resulting in fewer highly focussed scheduled activities, and more (unmanaged) creative interactive time in natural environments.

Your NP2 is completely consistent with the underlying intent of helping people visually prioritize their relationship with and interactions in natural environments. The measures (or indicators) you suggest make tremendous sense – scale, intensity, duration, frequency – and are beautifully argued.

The only thing I might suggest is that we need language that can also fit those who live in rural areas. The word “neighborhood” applies only to urban and suburban communities, and excludes us rural folks. Yet, while some might think that the nature-deficit problem lies only in cities, I would suggest this is far from the truth. Just as we have learned that the concept of “food deserts” applies just as much to rural areas as to urban, so too the issue of having appropriate and meaningful access to nature is just as important for rural communities. Sure, the irony is even richer when rural kids are no longer able to walk the woods of their neighbors, or no longer able to freely walk in the streams or search for tadpoles, simply because access, once unbounded by fences or postings or lawsuits, is now limited by all. Hence, rural kids may end up being just as “shut in” as urban kids, but without even the grace of having friends within shouting, walking or biking distance. I realize the focus of Biophilic Cities is, of course, cities. But the work you’re doing has larger implications that extend to the minority of our population that lives out beyond the city borders. Perhaps I’m all wet – perhaps ‘neighborhood’ works just as well for for rural areas as for urban? By my ‘neighborhood’ isn’t really anything – I have only two neighbors on my dirt road of several miles. So is my neighborhood really about the neighbors, or is it , more likely, about a local mini-biome? Let’s put out a challenge to folks now: help us find language that is rural/urban-neutral, so that the applications of the NP2 can be universal.

Cheers to all, and many thanks especially to Tim, for moving this concept forward!

Reflections on Tanya Deckle-Cobb’s “The Nature Pyramid(NP)” (First Draft 8.23.2012)

In his short article “Exploring the Nature Pyramid”

[http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2012/08/07/exploring-the-nature-pyramid/],

Tim Beatley, as Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities at the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture, has made a significant departure from head-down problem solving. He has gone from an intuitive acceptance of an illustration’s connection to a subject or field of study that does not yet exist to an academic confirmation (rubber stamp) of the illustration. He says this image is the place to start, and wants everybody to bring the content forward.

Thumbnail of Tanya’s NP:

http://ien.arch.virginia.edu/projects-current/nature-pyramid

In most cases, the subject is filled out first by academic research, peer reviewed, and then somebody with credentials finds a image that would graphically equivocate the consensual left brain insights. Like the Periodic Chart of Chemistry, or Erikson’s Epigenetic Chart, or The DNA Double helix. These are benchmarks in the history of information design. Is there a word for the intrinsicate “harmonia” between idea and its graphical representation? Chinese Mandarin?

What excites me about Tim’s first rendition of Tanya’s “synthetic-collective” metaphor, i.e. NP, is that he has chosen space and time as content represented by the metaphor. I agree, happily.

Here’s is why I’m happy. This approach is viable with Gardner’s Multiple Intelligence psychology, which has recently recognized “nature intelligence’ as innate (biophilia?). A nice confirming “overlay.”

Gardner’s Eight Intelligences:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple_intelligences

Another Gardner intelligence is “spatial”. Tim’s first rendition has “space” on one side of the pyramid; two pluses: nature works and space works. But “time” on the other side is a problem. The first problem is that this illustration is a triangle, with three sides! A three sided figure is not called a pyramid. A pyramid is four sides. And the second problem is that Garner does not recognize Time as an intelligence. Elsewhere, I have argued that he is wrong.

In any case, I am unhappy with all of this. Borrowing an image and its title uncritically has lead us immediately into information design’s recurrent problem : metaphoric fog. In my first attempt to verify this illustration’s power to hold/model content, in hopes of it having the power to hold more, or connect to more, I have a problem that takes me back to the graphics problematic “ontological framework.” For instance, on the “time” side of the NP, where do you put events that have 10 year cycles?

Here, as a root solution, I would take the momentum of enthusiasm for one three sided pyramid and add three more three sided pyramids, making a circle of four pyramids with their apexes inward, creating an inner circle. This composite figure would then be the “ontological framework” of future content testing. For Tanya’s/Tim’s NP as it is, I would place “space-time” in the center circle, and go from there. This is all play to me.

I have been practicing this kind of information design (“subject braiding”) since the 1970’s, and have yet to convince anyone of its efficacy. For the curious, partial results can be found at very skinny web site-in-progress at fivelements.net. And a project description of this approach is at http://shanti.virginia.edu/projects/1235.

Thanks for such a stimulating article.

Best wishes,

Clay Moldenhauer

College ‘63

Curry: Summer Visiting Artist ’90

Very interesting post, Tim! I also discovered your Biophilic Cities Project. Many thanks!

Tim, thanks for the great contribution: not only for presenting this insightful pyramid, but also for so many intriguing questions ! Actually, I love your book Biophilic Cities, it has been an excellent reference for lectures and classes. It helped me also in the book I will publish early next year. I will add the “nature pyramid”, I believe it will help people think about their own experiences in urban areas and bring more attention to the role of urban nature.

In Rio we have urban natural parks in the middle of densely urbanized areas, where people can go every day. An intriguing question for me is why many people have never gone to rainforests, mangroves and sandbanks protected areas even if they are close enough to go daily? Maybe the reason is the offer of nice beaches, where people exercise and socialize. Actually nature surrounds us, but are far from the car-oriented streets, where the trees are old and decaying.

I am looking forward to learning more about your research.

I would also add life stage to the pyramid. Might it be possible for a child to have a more immersive nature experience in a smaller, everyday, natural space than for an adult in the same space?

When Tim presented his nature pyramid concept recently in Portland is stirred quite a buzz. While it will be wonderful to back this concept up with empirical data, I have 30 years of practical, on the ground experience having led thousands of field tours throughout the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan region—via foot, kayak and bicycle.

My purely anecdotal response is people desire daily, intimate contact with and respond more strongly to their nature experiences in the city than in a wilderness setting. I say this having led many nature trips into the Pacific Northwests forest and desert wilderness areas. Speaking only for myself, however, I find myself reacting more viscerally to close encounters with wildlife in the city precisely because we have been conditioned to “expect” such encounters in the rural wildlands, but in the city—-even though I’ve had plenty of such encounters over the years——–it never fails to surprise when an osprey, eagle, peregrine, or great blue heron appears, juxtaposed to the built environment. I think it’s the contrast that excites.

On three recent occasions I had what I’d describe as uplifting spiritual experiences that I have no doubt affected my mental and physical well being. A few weeks ago, not more than a mile from my apartment in NW Portland [the densest neighborhood in the city] I heard high pitched warbling of what initially sounded like a young red-tailed hawk begging for food. On looking skyward there were seven bald eagles ketteling two-hundred feet overhead. A few days later, sitting on my front stoop, i heard what had to be a falcon overhead. Looking up I saw six peregrine falcons, presumably the four young and two adults from the nearby Fremont Bridge. And just a few days ago while taking visitors to Tanner Springs Park in the very densely developed Pearl District we observed an osprey diving into the park’s shallow pond, going after small koi a nearby resident had illegally dumped into the small wetland feature.

Had I been in eastern Oregon’s high desert I would have found these encounters a pleasant, but expected pleasure. It was the urban setting that amplified the pleasure for me, and dramatically affected my mood for the rest of the day. These experiences are not rare in Portland and I firmly believe they are at the base of Beatley’s nature pyramid. Every poll conducted by local park providers or our regional government, Metro, indicates that residents throughout our region desire such encounters with nature where they live, work and play—-on a daily basis.

Mike Houck, Director

Urban Greenspaces Institute

Portland, OR

Excellent idea this comparison with the nutrition pyramide, especially to convince city developers! A german saying : Alles geht durch den Magen!

Working with schools, events and camps I have learned to ‘put it on the schedule’. If it’s not on the schedule it doesn’t exist for many people. People do notice and incorporate these models into daily thinking. They become a part of our cultural identity and collective unconscious. It ‘puts it on the schedule’ so to speak. I think this could be a great way to move culture towards recognizing the value of natural spaces and experiences.

Really interesting post. One goal I have for my very urban CUNY students is to help them appreciate that they live in an environment. Too often for them the environment is something they go to visit elsewhere. For this reason, one mission of the CUNY Center for Urban Environmental Reform is building awareness of urban environments as living environments.

What an intriguing and novel idea , the Nature Pyramid! I am anxious to hear more about how this idea gets “populated” and substantiated with experimental and observational data. Proponents of Wilson’s Biophilia may be interested in a recent article entitled “Urgent Biophilia: Human-Nature Interactions and Biological Attractions in Disaster Resilience” at: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss2/art5/

Relating back to the Pyramid, the concept of Urgent Biophilia asks questions about drivers towards human-nature interaction, or motivations, perhaps a third axis to consider in addition to spatial scale and frequency /duration/intensity.

In any case, Bravo! A great read… thanks!