The Venetians built a remarkable city made up of close-knit island neighborhoods within a briny lagoon, centered on fresh ground water cisterns in the middle of sand filled public plazas called campi. There are few cities where one feels so in touch with nature, in the stone of the buildings, the light bouncing off the remarkable reflective water of the lagoon and canals. This is the special nature that envelops one’s body moving through that great city.

New Yorkers built a grid of reflective towers, which offer residents the pagan delight of “Manhattanhenge,” when the sun sets directly at the perspective endpoints of its 155 parallel cross-town streets. On ordinary days, light bounces mysteriously from high towers blocks away into narrow airshafts of old-law tenements. Its grid slopes to two arms of the Hudson/Raritan estuary, and a bike riding tenement dweller knows how to escape the seasonal extreme heat or cold precisely according to a local knowledge of the glass-canyon microclimates.

Nature loving Bangkokians believe all things are alive, and offer food, flower garlands and incense to the ghosts that inhabit their city. As part of their animist roots, nature is an invisible force only partly felt through sensations of hope, dread or fear. Buddhist practice places nature in a realm beyond form and sense, but manifest in temples designed as models of the cosmos.

What all three of these cities face is the uncharted future of dramatic shifts in climate. Traveling between Venice, Bangkok and New York in 2011, I have seen the plight Venetians face with the high water of each high tide, a devastating flood in Bangkok that crippled a global industrial supply chain, and a ‘what if’ collective breath holding in New York as Hurricane Irene approached. Clearly urbanists and naturalists need to immediately address the dual challenges of rapid urbanization and climate change from a diverse range of cultural practices globally. In order to meet these pressing challenges we need to get beyond the ways we mentally separate nature and culture.

Philosopher Brian Massumi has introduced the idea of the nature-culture continuum (2002) to provoke us to go beyond the Enlightenment idea of a human/nature divide. He asks us to examine ourselves as moving, sensing beings within a surrounding Nature directly present as flowing matter-flux. The energy source of the sun together with water, the dominant element of the planet and our bodies, are the sources of life. Humans are mobile subjects in continuous interaction of sun energy and water evident in atmospheric deposition, transevaporation, photosynthesis and microclimates. Great city designs such as Edo-era Tokyo make physically evident in public life the natural-cultural continuum of maintaining energy, food and water supply, and the healthy reuse of waste.

Anthropologist and Sociologist of Science Bruno Latour (2004) asks us to abandon the idea of a big universal Nature in order to create a truly micro politics of ecology. For him Big Nature dominates the political project of ecology and prevents citizens from taking nature and science in their own hands from their own experience as a common and immediate project. Big Science, in its search for universal truths, tries to be above politics, but as a consequence removes nature from the cultural continuum of public life.

In spite of four decades of environmental achievements in the United States, urbanization since the 1970s has mostly taken the form of a massive oil-based, highly dispersed conurbation of consumption. According to The Global Footprint Network the U.S. now exceeds its bio-capacity by four times. Our new sprawling cities in the U.S. are consuming more and more diminishing resources, and since the 2008 economic crisis have become even economically unsustainable. Our contemporary cities may look greener, but they have displaced energy sources, food supply, water sources and waste streams beyond our immediate sensate experience as well as the public life.

The Architecture of the Nature of Cities

As an architect, I am fascinated by the ways the cities have been designed to variously reinvent, rename and reinterpret nature throughout history. Cities help us understand nature’s terrors and benefit from its immense resources. Humans are born and gain consciousness within the vast pre-existing and ongoing reality of nature, and now most humans are born in cities of one form or another, many in the U.S. growing up in the backseat of an SUV, watching a green world quickly fly by. In spite of the proliferation of vast artificial environments, we can never be separated from how we culturally interpret the nature that surrounds us and that constitutes us as living beings.

This blog presents a great opportunity to begin to find better ways of understanding the Nature ofCities as a natural-cultural continuum instead of the act of separating out examples of nature incities. The operative word in this title of this blog is of.The definitions of both “nature” and “city” are inherently political and open to a wide variety of interpretations based on our particular inherited culture and way of living.

The important book by Italian architect Aldo Rossi, (1966, translated to English in 1982) The Architecture of the City repositioned the way architects saw cities. His simple title contains a radical criticism of modern architecture’s focus on object buildings set in a naturalized landscape. Instead, he taught us to readcities as collective cultural-natural artifacts with both fixed and changing elements.

Morphological and typological analyses were Rossi’s tools, much like a botanist he taught us to study and classify the spatial and temporal aspects of the city. He lead the way for generations of urban readers of American cities – including Reyner Banham (1971) finding The Architecture of Four Ecologies in Los Angeles, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour, (1972) Learning from Las Vegas, Rem Koolhaas’ (1978) Delirious New York, and Albert Pope’s (1997) Ladders of Houston. These studies reveal the different nature of city cultures.

My own work began with a comparative mapping of New York and Rome as cities in the process of adaptation and change over time due to various political and economic ruptures (Transparent Cities, 1994). When I conducted the research in the 1980s New York was just recovering from the economic crisis following the oil shock. I found inspiration in the resilience of Rome, which collapsed in the 6th century with the destruction of the road, food supply and water infrastructure of the imperial city, but over the next millennium developed a self-sufficient urban model where half of the city within the old walls was devoted to food production, and the river became the source of water and hydropower.

The Ecology of the Nature of Cities

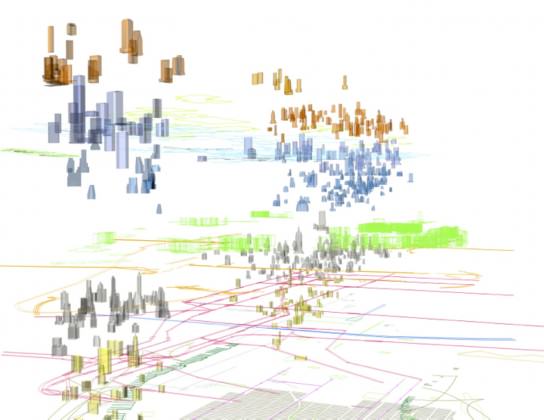

With the emergence of digital technology changing the means and tools for communicating and designing cities, I founded urban-interface, an urban design consultancy specializing in the relationship between design, ecology and media. One of the first projects in this area was an interactive on-line analysis of the formation of Manhattan’s central business districts for the Skyscraper Museum called Manhattan Timeformations, a project that makes legible the esoteric knowledge of speculative real estate development.

After Timeformations was published in Wired magazine in 2001, I got an e-mail from Morgan Grove of the U.S.D.A Forest Service. It seemed that the project resonated with scientific researchers at the Baltimore Ecosystem Study (BES), who were examining the processes of urban patch dynamics and succession. Since then, I have lead an Urban Design Working Group at BES, where Massumi’s natural-cultural continuum is most evident in the watershed continuum and patch-dynamic theories for the research, while Latour’s political ecology plays out with the collaborative work between social scientists, local non-profits and ecologies under the Human Ecosystem Framework.

There is an architecture of the city, as well as an architecture (physiognomy) in natural processes such as ecological succession (Picket, et al 2011). Ecologist Steward Pickett also uses the preposition ofas a provocation when he asks us to consider the ecology of the city rather than ecology inthe city (S.T.A. Pickett, W. R. Burch, Jr., and S. E. Dalton ‘Integrated Urban Ecosystem Research’, Urban Ecosystems, vol 1, 1997, pp 183–4). Together with Pickett, I have postulated a metacity theory as a way to bridge the gap between the architecture and ecology of the city. In this approach the entire city is relevant for analysis by a wide array of actors. The ecology of the city becomes the driving cultural metaphor for citizens and architects as well as scientists. My interest in the metacity is to understand how the ecology and architecture of the city can co-evolve as part of a natural-cultural continuum.

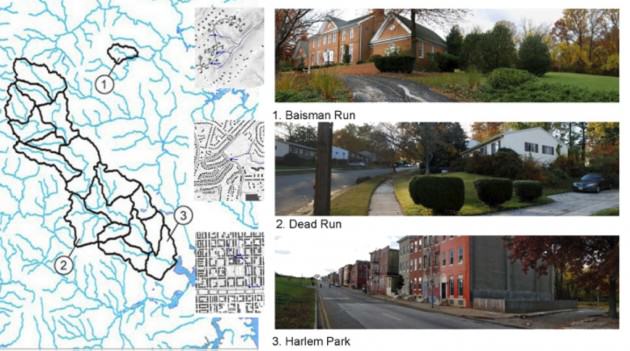

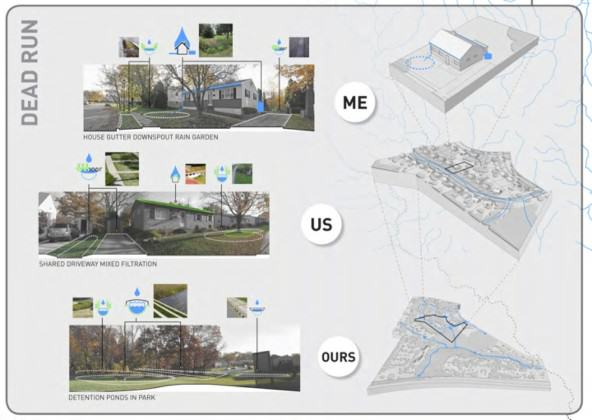

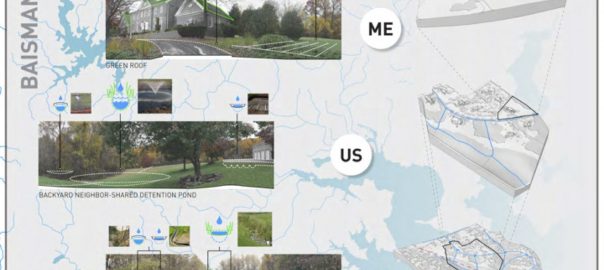

For example, as part of a N.S.F. Biocomplexity study, we worked with a team of social and bio-physical scientists to study how changes in peoples vegetation and water management habits could lead to larger structural changes in the form of the city to mitigate non-point nitrogen pollution in the Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the U.S. east coast, downstream from Baltimore and Washington, D.C. We looked at three sample sites that represent completely different ideas within the evolving natural-cultural continuum of Baltimore.

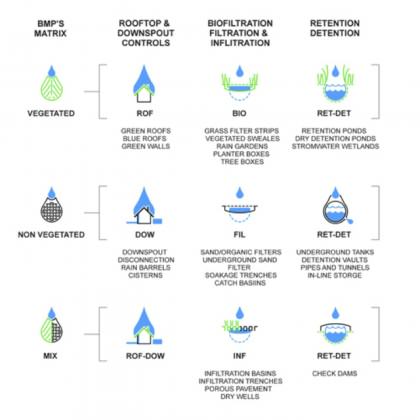

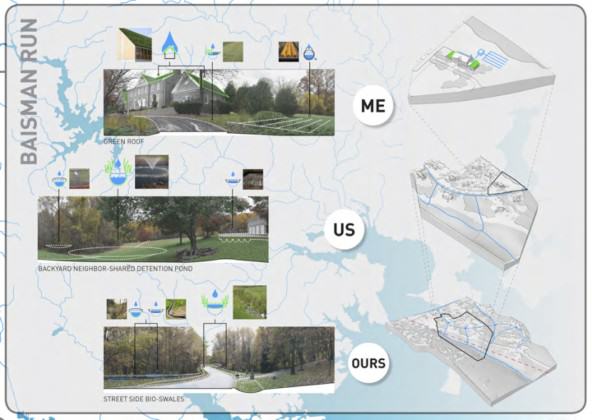

Our design work at urban-interface tried to imagine the choices each resident could make individually, or in partnership with neighbors, or at a municipal level to enter into a nature-culture continuum to improve the quality of Chesapeake Bay. We created a matrix of best water management practices, and presented three options for each neighborhood: what you could do yourself on your own property (me), what you could accomplish in shared backyards or by cooperating with neighbors (us), and what was possible to do on public infrastructure and right-of-ways (ours).

Homes in Baisman Run are within subdivisions regulated by Clean Water Act mandates, and are set back along cul-de-sacs from protected streams on five-acre lots. The large five acre lots can accommodate septic systems which were designed to manage bacterial contamination, but do not prevent nitrogen export. Additionally, riparian setback regulations place the development along stream ridges, and fire access regulations and multiple car ownership means that there is large up-slope impervious pavement that accelerates rainwater into the streams, excising the streambeds.

The cultural choice to live in such close contact with a highly scenic nature is having severe unintended consequences on the watershed as a whole.

The older suburb of Dean Run consists of ranch houses on ¼ acre lots with separated sanitary and storm sewers. These communities were built between the two World Wars when a progressive era of provision of sanitary infrastructure and public parks was paramount. Here the stream is partially piped, but comes to the surface to flow through neighborhood parks, where water monitoring has shows a great deal of nitrogen processing is taking place in slow moving, organic litter-filled pools.

In the City of Baltimore, row-house blocks dominate. All streams are piped, and parks and open spaces, such as residential squares, were designed for passive recreation, not for ecosystem functioning. With a history of urban renewal and disinvestment in these old neighborhoods, vacant land and buildings, however, as Timon McPhearson has shown in New York, allow for new natural-cultural resources. Harlem Park is a neighborhood in West Baltimore called Watershed 263, where many community green infrastructure projects are working towards taking advantage of the open land as a community natural resource.

Embracing the Nature-Culture Continuum of Cities

Both ecologists and architects need to together embrace the nature-culture continuum and to examine all the ways Nature is imagined, framed, viewed, cultivated, and used by city dwellers, as well as when it refuses to be tamed the way we expect it to. Our own intimate engagement with Nature emerges inside a particular natural-cultural continuum. Various human social groups construct different views of nature and act according to their particular sets of beliefs. This is the basis of the micro-politics of ecology. Some of us see the trees, some the shadows of passing figures on the sidewalk, and some watch the way the rain gathers litter in the curb. The political ecology of the cultural/natural continuum is multi-layered, multi-nodal, overlapping, conflicting, always evolving and increasingly limited.

In addition to marveling at the different forms the nature-culture continuum have taken in Venice, New York and Bangkok, I have also been working with colleagues at New York’s Parsons The New School for Design, Università IUAV Venice, and Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok on the challenges of climate change across huge mega-regions. BES provides a model of how science and design, ecology and architecture, might work together as part of a nature-culture continuum. Its focus, which is quite different from the search for abstract universals of Big Science, is on action based knowledge production and design based research.

I encourage all readers of this blog, whether you think of yourself culturally as a naturalist or an urbanist, to participate in the nature-culture continuum in order to better understand and participate in the ongoing process of the Nature of Cities.

Brian McGrath

Newark, NJ

USA

Leave a Reply