It is an irony that despite the magnificent natural beauty of Rio de Janeiro, the city itself is largely devoid of functioning nature. It is now time for Rio to not only to host global events such as the World Cup and Olympics, but to host its primary nature, not outside the city, but in the middle of its streets, plazas and buildings. This blog discusses a case study – the greening of the Carioca River watershed that emerges from Tijuca National Park – as an example of what we could accomplish for the good of all Cariocas (which is what residents of Rio are called).

The presence of nature is decreasing in the daily life of Rio due to the expansion of the impervious area at many scales, from street to district scale, architectural models of arid constructions and street tree plantings that are getting old. Slowly the nature is being “expelled”, transforming the city in an hot and arid landscape.

The city of Rio de Janeiro has a semi-humid tropical climate, with hot and humid summers and mild and dry winters. Climate change forecasts in the medium to long-term for this region indicate more peaks of heat and rain, more drought, a rise in average temperature and larger drought periods (Megacidades, Vulnerabilidades e Mudanças Climáticas: Região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro). The future may be one of environmental imbalance, mainly because of alteration of quality and quantity of water and strong changes of the vegetation land cover, plus other alterations to natural systems and their co-relations.

What can Rio, its government, and its citizens do to face these new challenges? Urban design issues focused on nature efficiency can be a response. Here are some conceptual experiments and designs on the potential presence of nature into the city.

Case study: the Carioca River watershed

Rio de Janeiro will host the World Cup and the Olympic Games in the coming years but it will also host global changes like rising temperature and more extremes of humidity. We know that ecosystems can be effective regulators of the environment, especially at local scales (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment), so we will propose nature, in this speculative exercise, as a method of regulating heat and humidity for our urban environmental scenario in the medium term.

To illustrate Rio’s current conditions and create contemporary design proposals to reverse the lack of nature and its immediate consequences, we will study the Rio Carioca watershed for its iconic abiotic, biotic and social status. It is unfortunately not valued by the city or many of its residents, but it will at least illustrate problems the city is facing in its everyday life but not in its political decisions. (See also here.)

The watershed of Rio Carioca has been occupied by humans since the dawn of colonial occupation because of its fresh water, firstly by local farms, later by industries, and then finally by planned residential neighborhoods. The Carioca River was a source of fresh water for most of the settler population. In 1750 the river was diverted to supply the downtown Rio’s fountains and the arches of Lapa aqueduct, which conducted the water, remains today. The aqueduct is now a historical monument is used as a bridge and is the most iconic element of this neighborhood. However, only a very few remember what was its original purpose.

A city between hills and lowlands

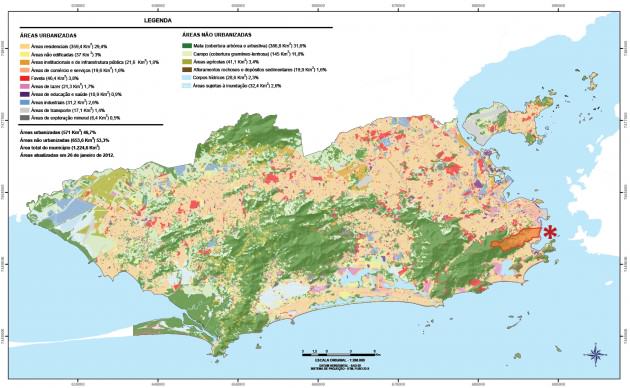

The geology of the city mainly separates the territory in two main classes that are hills of granite or gneiss and lowlands constituted by silt, sands or landfills. During the 20th century many hills were used for landfill and wetlands filled to create more territory near the ocean and the bay. This territory has been highly transformed by built infrastructure, and even its national park, Parque Nacional da Tijuca, was reclaimed, at the end of the 19th century, after coffee plantations drained most of the rivers of the city. Major Archer was responsible for planting 100,000 trees and restored this forest with native plants.

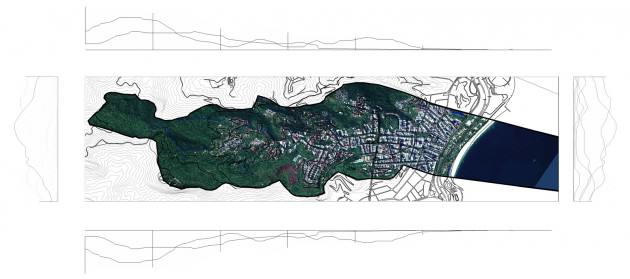

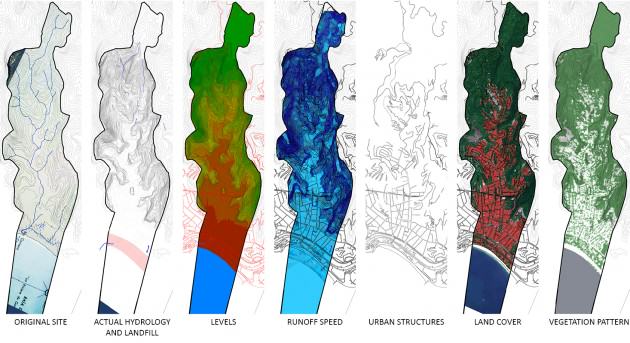

Most of the watersheds pass through these geologies and the natural lowlands were occupied by marshes, lagoons and meandering rivers. Nowadays the city is concentrated in the lowlands and and the natural history has largely been removed from the urban landscape. The Carioca River watershed, even if it is not the worst environmental example in the city, has a clear and strong gradient: green in the hills, but very grey in the city.

Blue system, lost river

Today the Carioca River has disappeared from the city. It is covered by infrastructure soon after it enters the formal city and only reappears near Guanabara Bay in the middle of Flamengo Park, a masterpiece of landscape architecture by Burle Marx. Ironically, the river passes through a sewer treatment plant as it arrives in the park, revealing the true official recognition by the authorities that the Carioca River is no longer a river but a sewer system.

We cannot hide our problems under the rug (or concrete) and it is time to rethink the role of water resources in the city and recognize that the health of our environment must be measured against the health of our urban waters.

Green systems, fragmentation and anthropization

Rio de Janeiro recently won the title of UNESCO world heritage site and reasons for winning this award abound in this watershed. For example, Tijuca National Park, an approximately 4000 hectare conservation unit (CU) created in 1961, successfully protects Atlantic Rainforest biodiversity in the middle of the city, although it has always suffered influences from the actions of Man (As marcas do homem na floresta – História ambiental de um trecho urbano de mata atlântica). Nowadays the sum of all CUs in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro represents one third of its territory. However, most of these conservation parks are at the edges of the city with few entrances and distant from the central cores. On the one hand they provide excellent stages for conservation, but their remoteness means that most residents have little contact with nature except for distant views. Natural landscapes in Rio are more background than foreground.

Full city or empty nature?

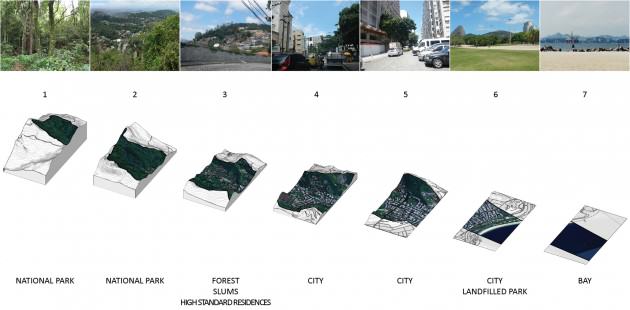

To examine the watershed more closely we divided it into seven parts of equal length as a tool for interpretation and analysis – like botanists do in surveys of biodiversity – drawing grids and surveying parcels on the land. Summarizing, we can read on the landscape the following four main typologies.

- The top of the hills with scenic views acting as natural belvederes and monuments, such as the Cristo Redentor statue – highly touristic sites but only suitable for short visits.

- The border between the forest and the city, where there are expensive residences occupying big parcels and slums situated in between infrastructure and residual spaces.

- Middle-class residential vertical neighborhoods and their infrastructure.

- A large modernist park on landfill areas.

Reading this territory it is clear that the gradient of green to grey is also a gradient of population density in a city that has been emptied of nature. When I say nature I mean efficient ecosystems, not man made gardens with mainly esthetic purposes. So actually we have quite an empty city with a full nature only around the city at its edge.

The forest

Tijuca National Park does a really great job at interpretation for visitors, with all of its trails mapped and signage in place. It interacts actively through neighborhood meetings with all communities touching its border, but the two million+ visitors each year are mainly tourists who enter into a funicular in the middle of the city, jump out of it when arriving at the Corcovado statue (Cristo Redentor) and return after taking a few pictures of the city and its unique territory from above.

It is a missed opportunity that so many people from all over the world pass through the forest but do not have real contact with it or an understanding of its particular ecology. This is the point that should be better developed in one of the biggest urban forests of the world: connecting the forest and the touristic points with accessible and educational trails expanding the tourists’ knowledge of one of the best fragments of Atlantic Rainforest and its ecosystem services, such as biodiversity habitats, atmospheric and temperature regulation and water purification.

The border between the forest and city

This area is complex, with a mix of environmental, urban and historical restrictions and sometimes many public owners, such as the city, the state and the federal government. There is interpenetration of private and public spaces and some “nobody” places that are, for example, the buffer zones around energy and transportation infrastructure and properties of undetermined ownership. This area needs to be activated ecologically, and given sustainable uses. For example, small scale slums have social and economic demand for natural land uses such as agroforestry. This border could be co-managed in a model of land use similar to the Satoyamas in Japan.

These borders experience significant pressure from ecological edge effects and invasive of species such as the jackfruit tree, Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam., which compete on the Forest floor with native species. An active and planned use with co-management of population and public entities will result in more security for the population and the ecosystems.

The city

In Rio our public spaces such as street and plazas suffer from deficient maintenance and no systemetic planning for urban trees and permeable surfaces (i.e., areas without concrete where water can be absorbed). The main activity of public agents in public spaces is just cleaning or tree pruning. There is still a culture of concrete as a symbol of modernity, which results in an urban environment that acts more like a bathtub than as a natural system normal water flow and biodiversity.

Our proposals look to increase vertical biodiversity as a response for the vertical city that occupies most of the watershed with urban territory that lacks trees, soil, and permeable surfaces. Our idea is to use the huge range of epiphytes of the Atlantic rainforest that can be used for vertical gardening that does not require irrigation or strong support structures. Complementing this action would be extensive natural green roofs that could restore native herbaceous ecosystems of this biome and also serve as habitat for birds.

The big park

This is for sure a polemical issue because Flamengo Park is a masterpiece of designer Roberto Burle Marx, and a landmark for the city, its citizens and their common history. We will not enter here into a discussion about the park’s esthetic or historical value. The issue here is mainly about ecology and environmental efficiency of this 1.2 million square meters of public space.

Actually the park is almost a giant lawn with a really diverse trees but virtually no shrubs or wet zones. You can see gardeners cutting its lawn all year long making a lot of air and noise pollution…not so efficient for maintenance.

The way the herbaceous layer is designed should be rethought so as to complement it with shrubs, native grasses with only one or two cuts a year. The first ecological renovation could be implemented as a test for social understanding: the Carioca River, after it is no longer used as a sewer line.

Conclusion

This proposal is clearly a meant as a provocative and reactive initiative but it is surely aligned to the importance of the Brazilian biodiversity and its main biodiverse biome: the Atlantic Rainforest. It is now in time for Rio de Janeiro not only to host global events but to host its main nature, not outside the city, but in the middle of its streets, plazas and buildings.

Pierre-André Martin

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Leave a Reply