Coming just out of the whirlwind of the eleventh meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, in Hyderabad, India, from 8 to 19 October 2012, there are many reasons to celebrate.

The Convention brings together the governments of 192 countries to discuss policies, actions and investments in the conservation and sustainable use of all life forms on Earth, as well as access to biological resources and equitable sharing in the benefits of their use. Working in collaboration with global networks of cities and subnational governments for the last six years, and supported by relevant international and UN agencies, these governments adopted a decision (XI/8) in which they commit to continue investing in a specific Plan of Action to work with municipal and other local authorities, states, regions and provinces, and to promote the development, enhancement and/or adaptation of local and subnational biodiversity strategies and action plans in line with each country’s respective national-level plans and strategies.

Maybe even more concretely, more than 21 Parties have shown leadership in showcasing successful strategies, and (as reported by Kathryn Campbell in this blog recently) more than 400 cities and subnational governments worked in parallel and announced their own strategies, policy instruments and campaigns in support of the CBD. The increased mobilization of local and subnational authorities along the CBD targets, themes and issues over the last six years is arguably one of the most notable changes in terms of its potential positive impacts.

…but it’s not enough

This mobilization does not come a moment too soon, and it is still too small by orders of magnitude. Extinction rates for life of Earth are 1000 higher than the usual “background” rates over its geological history – we’re losing species at a rate comparable to one of the last five extinction events of Earth’s history, and this time the culprit is us. What is at direct risk is nothing less than the food we eat, cheap drinkable water, the air we breathe and between 40 and 57% of our economy (100% really, at the end…).

We can – and must – to do something urgently at the local level: most of the catastrophic loss of biodiversity foreseen for the 21st century, with its lasting and critical effects on development, food security, health, resilience to climate change and peacekeeping, is still ahead of us. And most of it, for better or worse, is and will be linked to the way we live in our cities, and more specifically with the way urbanization will happen in emerging economies.

Biodiversity is critical for urban quality of life, but most decision makers in urban planning and management are still not aware to which extent. Urban planners, legislators, investors, city managers, developers and organizations of residents have yet to realize how much their success and well-being are dependent on ecosystem services. We need to bring biodiversity and its services into the factors considered in urban governance and reduce the ecological footprint of urban life.

Not that the process of urbanization is an option: evidence shows that urban development and the evolution of human settlements is largely inevitable and organic (meaning that its growth evolves naturally and is affected more by global trends than by national governance or NGO or UN-level actions), but can be positively influenced through participative planning, incentives and guidelines that decouple urban expansion rates from unsustainable resource consumption rates.

We in fact have such schemes for such participative planning: governments in the CBD have committed to a well-designed Strategic Plan for the next 8 years, with a set of 20 specific targets (collectively called Aichi targets for the city in which they were adopted) ranging from environmental education to nature-friendly business incentives, parks and the contribution of indigenous and traditional knowledge, linking biodiversity to poverty eradication and saving money and generating jobs by using nature’s bounties. What is needed, as recalled by the Convention’s Executive Secretary, Dr. Braulio Dias, is implementation: bringing those good ideas into reality at national level and, increasingly, at local level. It will be the ecological footprint of the newly urbanized citizens that will ultimately make or break the chances that the Convention’s ambitious Strategic Plan on Biodiversity 2011-2020 and its associated Aichi targets are reached in 8 years.

A new form of urbanization, as outlined by former Curitiba mayor and well-known urban planner Jaime Lerner, or an urban bio-revolution as proposed by planner and activist Jeb Brugmann, are not only part of the solution for a more sustainable future: they are our only hope. The green economy is essentially an urban phenomenon, and needs local governance to work.

What we accomplished in Hyderabad

Let us begin by celebrating recent progress on this topic – aside from being a prominent issue in the Rio+20 conference last June, decision XI/8 is proof that green urbanization is a relevant issue in the Convention’s work. At the City and Subnational Governments Summit, an official event of the Conference, 12 national governments, 60 mayors and governors and 200 local and subnational government officers showcased coordination efforts between different levels of governments, and launched the Cities and Biodiversity Outlook, a reference publication on local action on biodiversity. Eight city leaders showcased their advances and commitment through a 37 panel “Biodiversity in Cities” exhibition. Announcements were made on Medivercities (a Mediterranean network of cities for biodiversity supported by the city of Montpellier, France) and a network of port cities and their associated scientific and technological institutions (called maritime innovative territories, MarITIN) proposed by Brest Metropole Oceane. New projects like URBIS, a proposal to set criteria and recognize local governments making a difference on the wider concept of biosphere reserve, and an approach to reduce impacts on nearby conservation hotspots called the BiodiverCity Hotspots concept were proposed by ICLEI, Conservation International and IUCN, and are gathering partners and momentum.

Culminating with the Cities for Life Summit in Hyderabad this October, the last six years have seen rapidly increasing cooperation with local governments in response to the global biodiversity crisis:

- In 2006, a global network of around 1,200 local governments, “ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability”, officially included biodiversity as a focus area and began a worldwide programme known as Local Action for Biodiversity (LAB) in which local governments are guided through a step-wise process towards improved biodiversity management.

- Curitiba, Brazil, 2007: at the first anniversary of the eighth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 8), Curitiba’s Mayor supported by Brazil, hosted a meeting of cities and biodiversity, following and making use of the momentum created by the COP and launching the official process of cooperation between different levels of government in the Convention.

- Bonn, 2007: Following Curitiba and driven by ICLEI and the City of Bonn in partnership with the Secretariat of the Convention, around 50 local governments gathered at a Mayors’ Conference in parallel to the ninth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 9). The “Bonn Call to Action” was subsequently presented by four Mayors to the high-level segment of COP 9.

- The CBD Global Partnership on Local and Subnational Action for Biodiversity, a cooperative forum of governments, networks of cities and States, as well as UN and international agencies, which became the main exchange platform for subnational implementation of the Convention, was launched at the IUCN World Conservation Congress in October 2008 in Barcelona. Today the Partnership brings together more than 1,200 cities, 50 subnational governments, 25 Parties, scientific networks like URBIO, UN agencies like UN-Habitat, UNESCO, FAO, UNEP and UNDP, as well as IUCN and the World Resources Forum. It has an advisory committee of cities and an advisory committee of subnational governments that communicate its advice to the CBD’s Ministerial Segment at every COP, and its members have been responsible for a number of catalytic initiatives over recent years.

- Nagoya, 2011: The same partners worked together to organize the largest side event of the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 10), where more than 600 participants from more than 200 local and subnational governments met at the “City Biodiversity Summit”, to indicate support for the implementation of the Convention and to illustrate their potential to contribute to that implementation.

Activities of the Global Partnership have shown that when they get mobilized, far from becoming a financial burden to CBD Parties, cities and subnational governments can be trustworthy partners in joint ventures on the sustainable use of urban biodiversity and in the reduction of footprints, co-financing and co-management arrangements involving a wide range of stakeholders.

Just imagine: one million mayors and 40-70,000 subnational heads of state can be involved, consulted, sourced and supported to identify, adjust and replicate greener policy and development solutions that achieve quality of life and protect nature and its services. On this avenue of work, we are still subject to Pareto’s Principle: the next 20% effort may result in quite significant (if not 80%) change. We should act now to take advantage of this momentum.

Let’s not reinvent the wheel – or should we?

As usual in the history of societal change, most technologies, solutions, programmes and initiatives needed to make these solutions happen are already available and beginning to get known through networks of practitioners and scientists. Curitiba’s green bus transportation system, Catalonia’s footprint analysis and its concrete recommendations for action, Singapore’s Cities and Biodiversity Index as a measuring stick to monitor progress, Bonn’s and Montreal’s experience in green area management, Hyderabad’s beautification efforts for COP 11, Sao Paulo’s green procurement policies – these examples are known and described in various publications. Solutions towards a more sustainable, and biodiversity-friendly city are available, and will come, to a large extent, from relatively large urban conglomerates in developing countries. Today’s laboratories for the most cost-effective and resource-efficient innovations in green urban technologies are more likely to be found in rapidly expanding cities in developing economies, and in better-organized slums of large cities.

Although many cities have attained high levels of excellence in greening their operations, funding and technology limitations today still restrict the “replicability” of those solutions. Also, solutions will require partnerships: many of the approaches described in the Cities and Biodiversity Outlook and recent related publications arise not from direct public governance, but through the spontaneous participation of citizens and associations of small-scale businesses. They may not come from “open” Western-style lay democracies, as many communities in more centralized countries and religious societies are showing very relevant leadership. They may not even come through new ideas: much of what works at the local level is really “reinventing the wheel”, a novel association of already tested mechanisms. With so many different solutions and technologies being applied around the globe, effective dissemination depends on networks of practitioners at local and subnational level, supported by national guidelines and programmes and articulated through regional and global exchange platforms, so that each subnational or local government can identify its specific menu of activities working in the context of their national policies. As shown in a side event at COP 11 by the World Resources Forum, Internet and mobile phone technology can help interested citizens monitor their biodiversity in cooperation with city park agencies. Gardening and green roofs can reduce temperature variation and cooling/heating needs, and using endemic species increases the resilience and decreases the cost of maintaining these patches of nature. Well-managed wetlands and surrounding hillsides can also harbor Satoyama-like sustainable and traditional food production units, contributing to urban food security and health. Hundreds of case studies are available in the literature available to the participants of the Global Partnership, and in the Cities and Biodiversity Outlook.

These solutions will be identified and disseminated by working closely with subnational and local authorities. They need to be involved and consulted from the inception of any biodiversity strategy or action plan, and this may often require capacity building for effective engagement.

But in my personal experience over the last years, and considering how effective this line of work is, it is still amazing how little this is actually done, at a larger scale and in more coordinated ways.

Clearly, implementation is site- and country-specific, responding to the legal and governance systems of each country. It will need to be adjusted and scaled up or down through equitable scientific and technical cooperation (whether North-South, South-South or triangular) with different levels of decentralization. The process needs to be informed through and coordinated with national and global processes, and if it should support implementation of the CBD, it needs to reflect the Convention’s guidance and tools, specifically the Strategic Plan and the associated Aichi targets.

What we need next

What we need is international and national support for local action.

We need different levels of government, and the players that support them, to coordinate action to protect nature as the ultimate source of all economic and social development (as someone said, you cannot eat money) and well-being in our cities. Our choices in urban living need to reflect our growing awareness of their impact on nature, nearby and thousands of miles away. Life in cities should offer natural experiences to its citizens as well. Cities, rural and natural areas are interconnected to the core.

The CBD Plan of Action on Subnational Governments, Cities and Other Local Authorities has been a key force as it has opened the way for support, from various quarters, for local and subnational governments’ implementation of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020. Local and subnational governments and their partners now intend to play a more significant and appropriate role in cooperation with their relevant national governments, in implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011‑2020 and achieving the Aichi Biodiversity Targets.

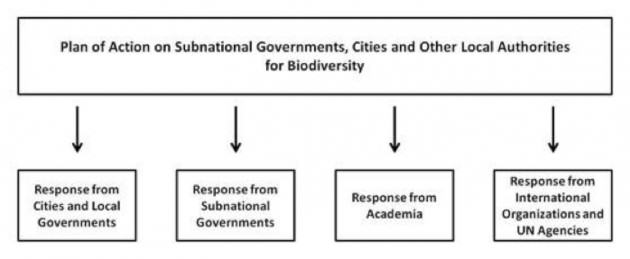

In a further effort to complement and respond to Parties’ fulfillment of the Plan of Action, the Global Partnership on Local and Subnational Action for Biodiversity proposes a response divided into four complementary strategies: a local government response; a subnational government response; a response from academia; and a response from the UN and international agencies.

The current global (and UN-led) policy development and governance structure is already aware of the need to build capacity of local and subnational authorities to engage with multilateral environmental agreement like the CBD, but it needs adjustments in order to respond more adequately to the size of the challenges. Some initial ideas would include:

- Greater participation of representative bodies of local and subnational governments in all multilateral environmental agreements such as the CBD, by being represented and involved, including in the elaboration of national strategies and action plans and reporting exercises.

- Enhanced and more flexible/adjustable funding (and technical support including match-making) for decentralized cooperation on biodiversity supported by the competent UN agencies.

- Support to the development or enhancement of local and subnational strategies and action plans in line with national policies and international agreements.

- Consistent capacity building programmes for local and subnational authorities on the implementation of the CBD. For instance, effective technical helpdesks for local authorities to learn about best practices and benchmarks (such as ICLEI’s Cities’ Biodiversity Center in Cape Town) can disseminate solutions and coordinate training and cooperation initiatives.

We need to show local governments the wheel, and they remake and adapt it as fits their needs, culture and society.

Based on the encouraging results of COP 11 for subnational implementation, I look forward to the next steps and to another City Summit at Korea, the accepted venue of COP 12 in 2014 and a very active Party when it comes to subnational and local action for the CBD.

Oliver Hillel

Montreal, Canada

Leave a Reply