Like an ancient prophet, armed with forebodings of doom and destruction, Hurricane Sandy bore down on New York City in the early hours of 30 October, 2012. An extra-tropical cyclone, a thousand miles wide and armed with hurricane strength winds, Sandy was only eight days old. A fitful infant terrible, Sandy had already visited havoc across Jamaica, Cuba, and the Bahamas; had been a tropical depression, a hurricane, a tropical storm, and a hurricane again; and might have spun without further harm into the north Atlantic Ocean, had not another, weaker storm from the Pacific coincidently crossed the continent on an intersecting trajectory. Sandy abruptly turned west and made landfall over a spring tide, exaggerated by the fateful alignment of Earth, sun and moon. The resulting winds and waves took the lives of 79 people in New York and New Jersey and caused an estimated $60 billion in damage, the second most expensive natural disaster in US history. (Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is first.) For the millions who lived, routines were disrupted by loss of power, then loss of fuel. Business ground to a halt. Lower Manhattan was dark for days. Hospitals were evacuated, subways flooded, parks emptied, schools shuttered. Only the salt marshes, a light green, grassy fringe along protected shores, seemed unmoved by the storm.

A prophecy is a message, a communication from beyond the ordinary ken of human beings. Prophets come to describe what is and to foretell things to come if we refuse to mend our ways. What was the prophet Sandy trying to tell us about the nature of cities? What was Sandy’s message about the nature of New York?

In the days immediately following the hurricane, it was hard to know. The loss was too near, and the damage too extensive for anyone to address anything but the direct perils and mourn the losses just experienced. But now some time has passed. Some sixty days and nights later, and with the perspective of a new year just begun, we are given a new opportunity to re-assess what we have learned.

Sandy teaches us that it is not enough to be intelligent, we must also be wise. Wisdom is more than intelligence. Where intelligence aims to know facts about the world, wisdom is the use of that knowledge to achieve what is valuable; that is, to choose just and generous ends and to act with courage and deliberation to advance toward them. An intelligent person knows what to do; a wise person does it. In the twenty-first century, we have much knowledge, but often seem to lack the wisdom to apply what we know. Prophets appear to give us the opportunity to change.

And what do we know when it comes to cities and storms? In New York and New Jersey, it is fairly clear what nature intends as a defense against bad weather from the sea: barrier beaches and dunes block the coasts and behind them salt marshes absorb the surge.

Barrier beaches are long, thin, low islands that form parallel to the shore along wave-dominated coasts; they are shields of sand. Clearly evident on satellite imagery of the south side of Long Island and along the Jersey shore, barrier beaches continue in a long line south to the Carolinas and Georgia warding the eastern edge of North America. In New York City, Coney Island in Brooklyn, Far Rockaway in Queens, the South Shore of Staten Island, and the FDR Drive at East Houston Street there are ancient barrier beaches, which old maps show were once surmounted with dunes, in some places thirty feet high, bulwarks held down by grass.

Beaches and dunes form through the movement of sand, lifted out of the ocean, and deposited on-shore by wind and water. They are unstable but not uncertain; guardians that never collect a day’s pay nor require maintenance except leaving them alone to do their job. Hurricanes and Nor’easter storms infrequently but dramatically rearrange the details of the geography of these protectors by rearranging beaches, shifting dunes, and forcing open or closing shut tidal inlets, leading to the shallow basins behind. March 4, 1931; September 21, 1938; September 14, 1944; March 6, 1962; October 30, 1991; December 11, 1992, all mark earlier prophetic visits in advance of Sandy. In between times, the everyday inhabitants of the shore, sanderlings, dunlins, sandpipers, and killdeer birds, play along the tidal margin, coming and going with each wave, eyes and ears attuned to the atmosphere, ready to fly to safety when poor weather threatens.

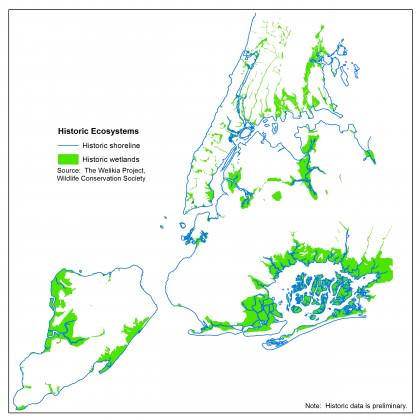

Behind the beaches once stood, and still occasionally do stand, extensive salt marshes inhabiting shallow bays and inlet waters. Jamaica Bay, Coney Island Creek, Great Kills on Staten Island – not to mention Flushing Meadows, Newtown Creek, and the southern Bronx River, elsewhere in New York – were all once great territories of salt marsh and seagrass, the second line of defense against great storms. Salt marshes, or salt meadows as the old-timers knew them, are peculiar, grassy ecosystems that form in the inter-tidal zone; dry on the low tide, flooded on the high tide, salt marsh plants and animals make a virtue of existence on the edge. Most can’t live there. Plants can be drowned like we can, needing fresh air to breathe, and salt desiccates all, so the plants and animals that manage to survive there have special adaptations, not only to flooding, but flooding by salt water. Spartina swards, for example, have special structures to carry oxygen from leaves above water into submerged roots, and mechanisms to extrude salt out of leaves, so that running a finger along the blade returns a harvest of briny crystals. The diamondback terrapin, a local coastal denizen, actually cries salty tears to maintain its aqueous homeostasis. Adapt to stay, turtles tell, climbing above flooded burrows to catch falling rainwater out of a storm.

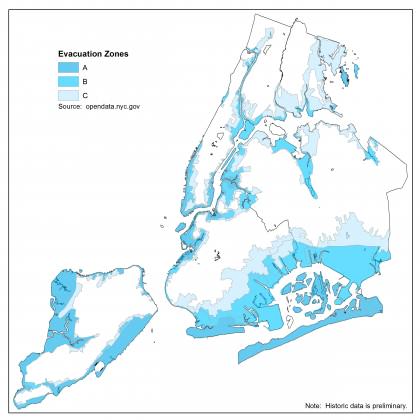

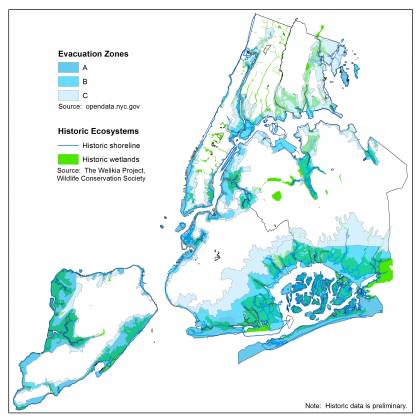

Given some perspective on time and landscape then, it may come as no surprise that the first places to flood in hurricanes are the past and present salt marshes. Overlays of the old, buried and forgotten, wetlands of the city and the new evacuation zones show a remarkable geographic concordance. Wetland edges are often filled in coastal cities to make new waterfront property, but because fill is expensive and labor is dear, they are often raised only just enough to raise them above the tides.

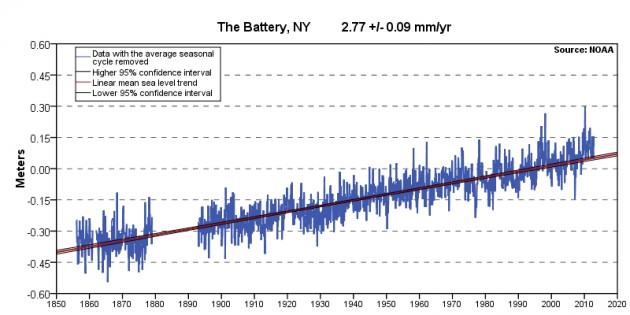

And what if the tides rise yet further?

Knowing these facts, wisdom suggests we should follow the strategies of sanderlings and the tactics of terrapins as we plan to spend the billions of dollars that will flow back to the city from the larger nation. Barrier beaches and salt marshes can protect us still, if we give them space, restore them to their former virtues, and enjoy the city behind them. We should by all means visit and appreciate the beach as long as we are prepared to retreat to havens on higher ground when tempests approach. And if we must leave some of our structures near the ocean’s swell, then for God’s sake (and our own), let us build only what is adapted to flooding and the motion of dunes and the surge of tides, so that when the next day dawns clear and bright after the storm, we too can return to celebrate the nature of a wise and resilient city on the ocean’s edge.

Eric W. Sanderson

New York City

Leave a Reply