Two of the most debated and challenging concepts in urban development are sustainability and resilience. How are they related? Do they mean approximately the same thing or are they distinctly different and can misunderstandings lead to undesired outcomes?

In this essay I will try to clarify the concepts, discuss two common misinterpretations and reflect on the many difficulties that remain in application in urban development.

Can a city be sustainable?

Most people would answer that this is not only possible but also given rapid urbanization, necessary for the planet to become sustainable. But my immediate answer is NO and here is the first common misconception we need to deal with. Cities are centers of production and consumption and urban inhabitants reliant on resources and ecosystem services, from food, water and construction materials to waste assimilation, secured from locations around the world. Although cities can optimize their resource use, increase their efficiency, and minimize waste, they can never become fully self-sufficient. Therefore, individual cities cannot be considered “sustainable” without acknowledging and accounting for their teleconnections — that is, their long-distance dependence and impact on resources and populations in other regions around the world.

Sustainability is commonly misunderstood as being equal to self-sufficiency, but in a globalized world virtually nothing at a local scale is self-sufficient. To become meaningful, urban sustainability therefore has to address appropriate scales, which always would be larger than an individual city.

The classical definition of sustainable development (Brundtland Report on Sustainable Development) focuses on how to manage resources in a way that guarantees welfare and promotes equity of current and future generations, in general addressing the global scale. However, in the urban context, research and application of sustainability have so far been constrained to either single or narrowly defined issues (e.g., population, climate, energy, water) or rarely moved beyond city boundaries.

Clearly what constitutes urban sustainability needs rethinking and reformulation, taking urban teleconnections into account. We will come back to this at the end of the essay.

Can we build resilience in a single city?

Similarly, most people would answer yes to this question and that a resilient city would be highly desirable and necessary. But again, my answer is NO, at least when it comes to general resilience, and here we deal with the second common misconception.

Firstly, a narrow focus on a single city is often counterproductive and may even be destructive since building resilience in one city often may erode it somewhere else with multiple negative effects across the globe (this relates to the distinction between general and specified resilience explained below).

Secondly, from historical accounts we learn that while there are some cities that have actually failed and disappeared (e.g. Mayan cities), our modern era experience is that cities rarely if ever collapse and disappear. Rather, they may enter a spiral of decline, becoming non-competitive and losing their position in regional, national and even global systems of cities. However, through extensive financial and trading networks, cities have a high capacity to avoid abrupt change and collapse and applying the resilience concept at the local city scale is thus not particularly useful.

What is resilience?

Resilience (see Resilience Alliance) has a long history in engineering science but the most influential ecological interpretation was developed by Canadian ecologist C.S. “Buzz” Holling in 1973. Resilience builds on two radical premises. The first is that humans and nature are strongly coupled and co-evolving, and should therefore be conceived of as one “social-ecological” system.

The second is that the long-held assumption that systems respond to change in a linear, predictable fashion is simply wrong. Complex systems are, according to resilience thinking, rarely static and linear, instead they are often in constant flux, highly unpredictable and self-organizing, with feedbacks across time and space. A key feature of complex adaptive systems is that they can settle into a number of different stability domains. A lake, for example, will stabilize in either an oxygen-rich, clear state or algae-dominated, murky one. A financial market can float on a housing bubble or settle into a basin of recession.

Historically, we have tended to view the transition between such states as gradual. But there is increasing evidence that many systems do not respond to change that way: The clear lake seems hardly affected by fertilizer runoff until a critical threshold is passed, at which point the water abruptly goes turbid. Resilience science focuses on these sorts of tipping points. It looks at slow variables (i.e. gradual stresses), such as climate change, as well as fast variables (i.e. chance events), such as storms, fires, even stock market crashes that can tip a system into another equilibrium state from which it is difficult, if not impossible, to recover.

Over the past decade, resilience science has expanded much beyond ecologists to include thinking among economists, political scientists, mathematicians, social scientists, and archaeologists. For a general overview see this video.

Resilience is now used widely in discussing urban development, but it is much more challenging than when applied to a lake, agricultural or a forest system. When most people think of urban resilience it is generally in the context of response to sudden impacts, such as a hazard or disaster recovery — for example Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and recently Sandy in New York City. How rapidly does the system recover and how much shock can it absorb before it transforms into something fundamentally different? This is often viewed as the essence of resilience thinking. However, the resilience concept goes far beyond recovery from single disturbances and it is here an important distinction is made between general resilience and specified resilience. General resilience refers to the resilience of a large-scale system to all kinds of shocks, including novel ones, specified resilience refers to the resilience “of what, to what” — that is, resilience of smaller scale-systems, a particular part of a system, related to a particular control variable, or to one or more identified kinds of shocks.

From an urban perspective, general resilience thus only makes sense on a much larger scale than individual cities (although specified resilience may be explored at a smaller scale). The concept of general resilience and scale lead us to another quite radical idea: change and transformation at the city level is necessary for maintaining resilience at the larger scale.

This may at first seem strongly counter-intuitive. Isn’t resilience about keeping systems as is and avoid change and transformations?

Transformation and resilience

To further explore this we need to put everything in a larger historical and global perspective, as shown below.

The relatively stable environment of the Holocene, the current interglacial period that began about 10,000 years ago, allowed agriculture and complex societies, including current urbanization to develop. This stable period is in contrast to the rather violent fluctuations in temperature in the preceding 90,000-year period. The stability induced humans, for the first time, to invest in agriculture and manage the environment rather than merely exploit it. Despite some natural environmental fluctuations over the past 10,000 years, complex feedback mechanisms involving the atmosphere, the terrestrial biosphere and the oceans have kept variation within the narrow range associated with the Holocene state. However, since the industrial revolution (the advent of the Anthropocene), humans are believed to have effectively begun pushing the planet outside the Holocene range of variability for many key Earth System processes (for full reference see here) including introduction of the concept of planetary boundaries). Urbanization represents one of the major processes contributing to this pushing pressure through, for example, green house gas emissions, massive land use change and increased resource consumption.

Maintaining resilience at the global scale — that is, avoiding that the planet passes a threshold and again enter into a new period of violent climate fluctuations — is therefore believed to require massive transformations at the level of cities. But what are these transformations, and what would trigger urban regions to employ them?

Coping vs. transformation

To explore this we will return to the basic principle in resilience thinking: a slow variable (like urbanization) may invisibly push the larger system closer and closer to a threshold (beyond which there would be radical change toward a new equilibrium) and that disturbances that previously could have been absorbed become the straws that break the camel’s back. However, urbanization does not just represent a slow variable. At the same time it is a process leading to higher intensity/frequency of disturbances through, for example, its impact on both global and regional climate change. Urbanization therefore represents a double-arrowed process and complex interaction between slow and fast variables. Conventional urban responses to disturbances such as coping and adaptive strategies may not only over time be insufficient at the city scale, they may also be counterproductive when it comes to maintaining resilience at the global scale.

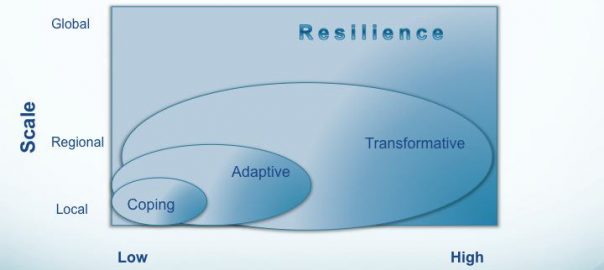

A coping strategy is often used to describe the ability at the local scale and often at the level of individuals (such as having savings on a bank account), to deal effectively with a single disturbance, with the understanding that a crisis is rare and temporary and that the situation will quickly normalize when the disturbance recedes. Adapting to change is defined as an adjustment at somewhat larger scales in natural and human systems, in response to actual or expected disturbances when frequencies tend to increase (e.g. building higher and higher levees in response to increasing risks of flooding) (see the image below).

Transformation strategies are employed when coping and adaptation strategies are insufficient and outcomes are perceived to be highly undesirable, A transformation is thus defined as a response that differs from both coping and adaptation strategies in that the decisions made and actions taken change the identity of the system itself, create a fundamentally new system when ecological, economic, or social structures make the existing system untenable. It also and most importantly must address the causes of the increasing intensity/frequency of disturbance, which necessarily may not be the case with coping and adaptation. There are numerous examples of urban regions already engaged in developing both coping and adaptive strategies in response to, for example, sea level rise, demographic changes, and shortage of natural resources. However, when intensities and frequencies of disturbances increase, building larger dams or higher levees may no longer protect a city from flooding or sea level rise. Instead, a transformation to, say, a floating city, may be the only viable option.

However, even if we would agree that a myriad of transformations at the local/regional scale is important for maintaining resilience at the global scale, current coping and adaptive strategies needs our attention since they may be counter-productive, lead to lock-in and prevent a transformation to be initiated. For example, this would include exploring the local-global synergies or trade-offs of different re-designing schemes of the supply and consumptions chains, evaluating different modes of re-designing urban morphology and transport and different modes of stewardships of ecosystem services within and outside city boundaries.

Resilience and sustainability — what is the difference?

So where does this take us when it comes to understanding urban resilience and sustainability?

First of all, for both concepts the local city scale is too narrow. Urban sustainability must include teleconnections and urban dependence and impacts on distal populations and ecosystems. Similarly, when building resilience at the global scale (i.e. general resilience), urban regions must take increased responsibility for implementing transformative solutions and, through collaboration across a global system of cities, provide a transformative framework to manage resource chains.

However, how do we then distinguish between the two concepts? Isn’t there still a substantial overlap? My view is that we may accept that the concepts are quite similar when addressing the global scale, but we may give them a distinctly different meaning when addressing other scales. At regional and local scales resilience could more be seen as an approach (non-normative process) to meet the challenges of sustainable development (normative goal). Treating resilience as non-normative at these scales is preferable since knowledge about the components of resilience could be used to either build or erode resilience depending on whether a transformation is desirable or not in a specific context.

I have above outlined some of the challenges with the two concepts, but there are many more. We will need a lively debate exploring even further the meaning of the concepts in an urban context and how cities may contribute to global sustainability and resilience through transformative actions redefining their role and become more of sources of ecosystem services rather than sinks and increasingly provide better stewardship of marine, terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems both inside and outside city boundaries.

It would be important to feed such a lively debate into the current efforts to develop a framework for the Sustainable Development Goals (for example, see here):

- Can we agree that the city-scale is too narrow for both sustainability and resilience analyses and policies implementing them?

- How should SDGs become relevant for urban development? How could scales be addressed in the SDGs? For example, how do we design scalable targets and indicators that link the local and the global scale?

- How should we use the resilience concept in relation to urban development? Could and should resilience be used in both a normative and a non-normative sense depending on scale?

I invite all readers to give their view!

Thomas Elmqvist

Stockholm

About the Writer:

Thomas Elmqvist

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at Stockholm University and Theme Leader at the Stockholm Resilience Center. His research is on ecosystem services, land use change, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.

How to city resilient and sustainable in same time

The need for new disaster resistant cities are the need of the day as we seen the disasters happening through out the world and mostly we respond late to that so. If cities becomes resilient then we can survive future disasters to certain level

Hi Thomas,

Nice essay. I like the transformation vs. coping notions as well as multiscalar considerations, I wonder where vulnerability as the opposite end of resilience fits into your conceptual model? In the US, Dr. Cutters work has looked at vulnerability from multiple systems perspectives, although I think the answers for transformation and adaptation necessarily are multiscalar – micro (individual/hh/firm/neighborhood/district) – meso (city infrastructure systems/food systems/ecological services at landscape scale), and macro scale (watersheds/airsheds/megaregions/substate systems/intermetro connections) to be truly descriptive of considerations. You need these levels in mind – because the notions of vertical and horizontal integration are a large part of sustainable cities and regions (and arguably aspects of resilience), but realizing that all urban resilience is inherently local as so much is determined by location choices, land use decisions (intensity/density) and compatibility with environmental, social and economic system considerations. I have a proposal in to US HUD to develop scenario modeling capabilities to learn about the tradeoffs at differing scales and interactions between the different dimensions of resilience, will know in next week or so if we fund. One possible thread you might explore in your work is adaptation of the logic structure of wetlands assessment in the US using the hydrogeomorphic approach (premise is ecological services but can be expanded using logic models)–this can be modified I believe- to create socially constructed resilience rating system that allows local stakeholders and experts to collaboratively define and understand key linkages and +/- feedback loops across resilience dimensions–thats where I am focused at present….cheers!

Hmmm…a system-of-systems approach with a scalar geographic dimension and disturbance/chaos component.

Great article as the other commenters have already noted. I wonder how many city managers, urban planners, disaster management officials, or social analysts take the time to identify and understand the relationships and friction points in their obviously complex systems?

I’m almost ready to start rescoping my observations of urban areas in either an “ecosystem” context or change the paradigm completely and look at them as a type of “organism” in a biological context, especially on how external influences create changes in the the ecosystem (or organism) and induce either short- or long-term change(s).

Really interesting article! I’ve been thinking about this myself but come to a somewhat different conclusion in my work with energy and resource efficiency. I think resilience needs to come from the neighborhood scale, so I found myself heading in the opposite direction from you. Our socio-cultural structure is largely a neighborhood structure, we can create self-reliant and resilient energy infrastructure most easily at neighborhood scale, food systems can be most easily built and nurtured at neighborhood scale, and so on…. Neighborhoods then form the cellular structure of a larger town or city, which then may be part of a larger regional cluster of cities. When neighborhoods are unsustainable, the city is unsustainable. I find super-dense neighborhoods (high rise downtowns) unsustainable and am leaning toward promoting a density limit (or perhaps a sweet spot) to achieve resilience. Some aspects of resilience must fall to the city at large, such as transportation infrastructure, but I feel most aspects of resilience are, and must be, achievable at the neighborhood scale.

A very interesting article, thank you! I’ve always though that resilience is a path for sustainability; we need to be resilient in order to be sustainable in a long term. My current research is on how we build resilient cities in earthquake prone environments. I’ve found – in the context of Chilean cities – that urban policies are a big problem in that concern. They are usually too tight and late; for example, land use is too specific and does not give room for aditional uses that open areas of cities have in times of crises. Beside, city master plans take too long to develop and when they are approved, the urban system is already under change. In this sense, I’ve found that social systmes and people’s behaviour in times of crises can provide a better contribution to urban resilience, mostly in environments where natural systmes are well conserved within or nearby cities.