The premises on which we build our cities and construct civilisation, and the extent and means by which we include nature in our cities depends on what values we choose to adopt. Our capacity to engage with the processes of nurturing the nature of our cities depends on how we see our roles as members of society.

Consumer or citizen?

When teaching tertiary students in the subjects of ‘Urbanity and Landscape’ and ‘Urban Ecology’, I would often ask a class whether they thought of themselves as consumers. Everyone would raise a hand. When I asked who thought of themselves as citizens, out of a class of around sixty I’d be lucky to see half a dozen hands go up; this was in the second or third year of university amongst the best educated young people of an ‘advanced’ western democracy — all putative young professionals likely to be charged with the significant roles in the ongoing development of our built environment.

Pursuing the point, I would try to open up some discussion by asking what rights one has as a consumer or as a citizen. The answers pretty much boiled down to the right to return faulty goods or not to buy things you weren’t satisfied with (as a consumer) and the right to vote (as a citizen). Going a little further and asking about responsibilities, I generally drew blanks.

Straw polls these may have been, but this is worrying stuff because I think it flags clearly that something is amiss in the body politic.

I don’t have the data to prove it (who would fund such a study?), but I am certain that billions of people around the world now see themselves primarily as consumers rather than citizens. They understand ‘freedom of choice’ to be about choosing from products on offer, be they from car manufacturers, washing powder purveyors or political parties. The concept of active citizenship is tenuous, if it exists at all.

The consequences of this are far-reaching and disturbing and affect the nature of cities.

Consumption or conservation?

What product do you offer a consumer that gives them the choice to value nature for its own sake? There are a handful of well-intentioned products that, as part of their cover price, offer to save whales or plant trees or whatever, but most cash-strapped consumers buy on price, not a sentimental regard for nature. At the same time, the nature of the marketplace is predicated on the consumption of natural resources in a way that precludes systemic change towards a system that values the conservation of resources. Scarcity adds value to resources and enhances them as targets for exploitation.

It’s an approach that didn’t help the Dodo, and it isn’t doing any favours to African elephants or Asian tigers. Their increasing scarcity renders them ever more valuable and as their value rises the incentive to hunt them is increasing. In a similar way the ecology of the Canadian wilderness is despoiled because its intrinsic value counts for nothing against the dollar value of the resources buried within it. As oil becomes more scarce its value is rising and it is becoming more and more ‘economic’ to employ expensive and destructive means to release oil from tar sands. In each case, as the perceived monetary value of elephants, tigers and tar sand wilderness increases, their intrinsic value counts for nothing.

It’s a vicious circle against which the consumer system provides no defences. Its hapless targets are either given little value unless they can be exploited, or great value as they become exploited. The values assigned by the market system work in direct opposition to almost all aspects of intrinsic value.

Development, and collective benefit

Land itself is only valued as it is developed and becomes developable. Notwithstanding cultural undercurrents that have long struggled to see recognition of the intrinsic merits of ‘wilderness’ it remains clear that wild nature has no monetary value until it can be consumed. A piece of prairie, stand of forest, or basin of wetland is seen as worthless unless and until it can be turned into ‘real’ estate. Once human ingenuity introduces the tools and processes capable of manipulating the landscape into usable real estate its monetary value rises. As a rule, its value continues to rise as its capacity to support living systems is diminished. The most valuable real estate is in the most built-up areas of heavily developed urban systems.

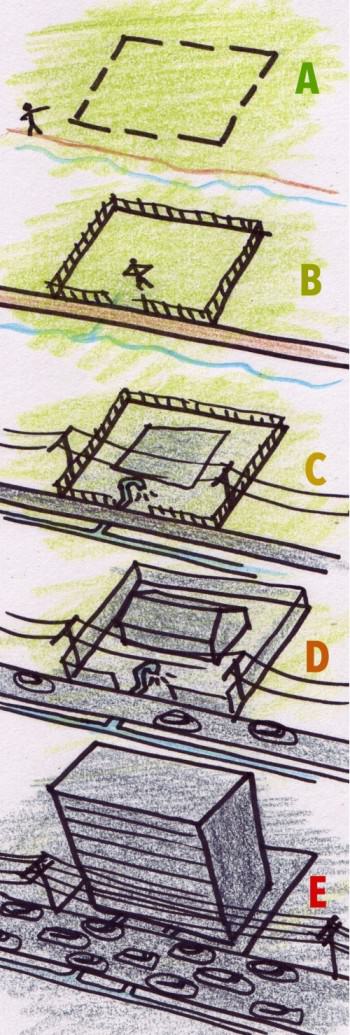

A – Undeveloped land

B – Land division + road = $

C – Reticulated power + water = $$$

D – Building + wider road = $$$$$

E – More building + more road + more power… = $$$$$$$$$$$

Credit: Paul Downton

It’s one of the ironies of mass industrial society that its preferred economic framework is focussed on satisfying the consumptive desires of ‘the individual’. This is where the fundamental value base of the consumer and the citizen, of necessity, diverge. The idea of being a consumer is exclusive. It is explicitly not about the greater good, it is about satiating individual desire and pandering to individual whims and the dictates of fashion for perceived personal benefit.

Consumers compete. Conversely, the idea of being a citizen rests on concern for the collective. Citizens make cities.

In order for any individual to gain advantages from it, a city first requires the creation of collective benefits. City infrastructure is a shared resource that contains such thoroughly mixed contributions from so many people that their individual contributions cannot sensibly be identified. Before any individual can walk down the sidewalk or drive along the road there has to be collective effort and acceptance of shared costs to create the sidewalk or roadway. It would be nonsense for any one individual to try and walk along only that part of the pavement, or drive down only that part of the road they paid for.

Archaeologists study the ruins of cities to gain insight into how people organised their lives in much the same way that a pathologist studies a corpse. A city is a social construct and every element of it betrays some information about how its people lived. This great construction depends on coordinated and productive behaviour by the individuals who bring it into being and maintain it.

A living city is no more a collection of buildings, roads and sewers than a living person is a mere collection of limbs, organs, arteries and veins. It is something that transcends the tribe as much as it transcends the individual.

Exchanging the wealth of human experience

Cities are places of exchange. That is their essence, their fundamental purpose; but the exchanges they foster and facilitate extend far beyond buying and selling in the marketplace. Social and cultural exchanges can, and do, exist without being tied to financial transactions. The value of cities cannot — should not — be measured only in monetary currency.

Unless you believe that all we are good for is to buy and sell goods and services, then reducing all relationships to mercantile exchange is to diminish what it means to be human. At best, it’s like marrying for money — it more or less guarantees a relationship empty of love, life and meaning. At worst, it is de-humanising, reducing the wealth of human experience to simplistic, one-dimensional measures of worth.

And it dangerously diminishes our capacity to appreciate the value of nature.

The same mindset that reduces the value of nature to what it’s worth in monetary terms is the one that speaks of valuing ‘natural infrastructure’ on the same basis as power grids and gas pipelines. If they deliver services, they have value. If they don’t, they’re worthless. In the monetary system a forest may have value as a stand of timber that’s worth more wood-chipped and dead than alive. Valued as natural infrastructure, a forest might be viewed as a useful part of a catchment that provides water for a city with a dollar value that reflects how much the water supply is valued by the markets at any given time. The rub is that in a monetary system the value of the forest varies in relation to changes in human affairs, distorted through the cultural prisms of the mercantile class, all bearing no direct relation to what the forest does in its natural state as part of the skein of living systems.

Understanding the value of nature in, and of, cities requires acceptance of its intrinsic worth as part of our life support system. The nature of cities can be measured in dollars or Yen or RMB, but that does not capture its worth.

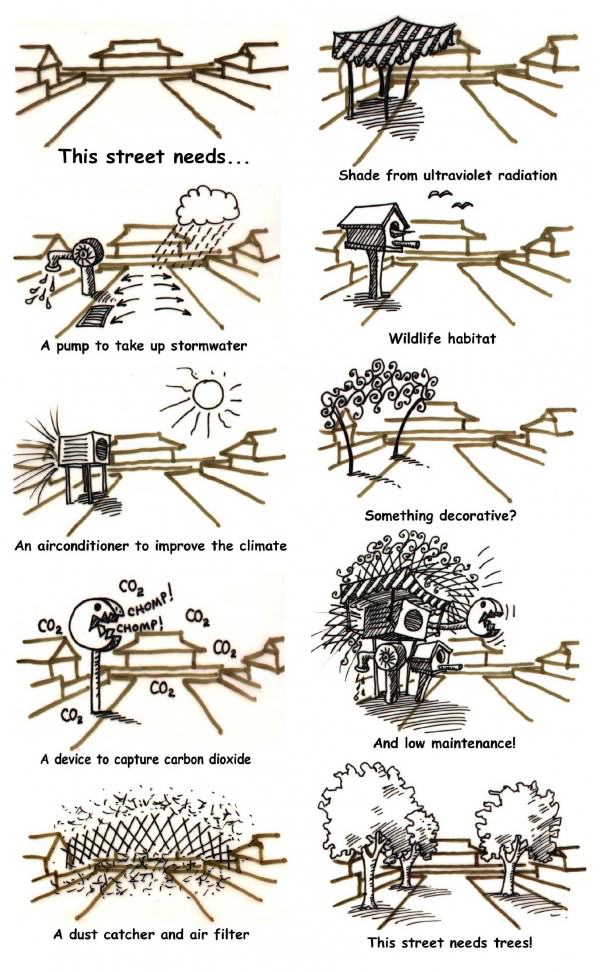

To say that a tree provides services which clean and oxygenate the air, absorb stormwater and provide shade that are altogether worth $xxx simply commodifies the tree and enables it to be listed in a set of financial accounts. But the merit of those accounts varies.

This is not to say that there is no merit in valuing ecosystem services in monetary terms, but the inherent danger in accepting commodification of the living world to any degree is that in an almost completely mercantile environment the commodified value becomes the only measure that is accepted in wider discourse. There is no actual equivalence between say, a thriving temperate rainforest (such as in Tasmania’s Tarkine region) and an open-cut mine, or between a Tennessee snail darter and a hydroelectric dam, and once the debate about their value is reduced to dollars, the argument about worth becomes subject to the vagaries and distortions of the marketplace and insidious assertions that ‘making a living’ is somehow more important than maintaining life.

Painting a picture

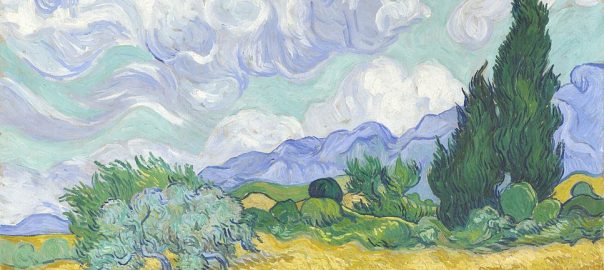

In any mercantile system ‘value’ varies. Perceived worth is negotiable. The coinage is based on fantasy — literally, on phantasms of the mind, albeit ones that a society chooses to share. The measures of worth derive, not from any absolute or grounded measures of things but from agreements to set a value on one or another aspect of human mental construction. Thus a 67 cm x 56 cm piece of canvas smeared with pigments and stretched across a timber frame may be valued at perhaps $80, or it may be valued at more than $80 million. Doing nothing but occupying space in a vault or hanging on a wall, over 20 years or more its value might rise from $80 million to nearly $150 million. Such has happened to the Portrait of Dr Gachet by Vincent Van Gogh (who never benefited personally from this perception of value and died in relative poverty).

This kind of perverse valuation can be seen again, all too clearly, when a two-dimensional representation of the complex, multivalent reality of nature using canvas and pigments possesses more dollar-value than the nature to which the artist was doing homage. One could buy many wheat fields with cypresses with the $91.5 million at which Van Gogh’s painting of that name is currently valued.

The nature of a city, in every sense, ultimately rests on the quality of its governance. That governance is informed by the values of its citizens and what they choose to prioritise. As consumers within the framework of the world financial system we choose to create socially agreed (if morally questionable) values for works of art that represent nature. Although our species is presently responsible for the biggest wave of mass-extinctions since the dinosaurs disappeared, as citizens and city-makers, we need to both identify and defend the full intrinsic value of nature within the framework of the city-making that represents our global civilisation.

The vagaries of the modern marketplace make it open to manipulation to a quite astonishing extent. The stock exchange crashes of recent and past history provide prodigious proof of that. What is worth a dollar today may be worth twice as much tomorrow — or not — but the value of nature is intrinsic. It is about living systems. Ultimately, it is about survival and if we allow the nature of our cities to be valued in terms of the marketplace rather than its integral necessity to our collective health and well-being, there is nothing to prevent it from going the way of the Dodo.

Paul Downton

Adelaide, South Australia

Thank you Paul for the inspiring article.

From my point of view in the changing environment of nowadays we have the chance to change faster through a more citizen centered city having always in mind our natural goals. However i think that the word id not spreading a lot. Terms like smart city or BIG DATA flow much faster than nature city or social ecological systems.

Do you expect human being to get closer to nature in this digitalized era? Now we can become more democratized. For this reason we could try to make our “real value” come back to the surface.

Congrats!

Very interesting read and fascinating to see a very different perspective. In parts of UK and France, financial amenity values have been placed on natural landscapes and elements within it, particularly trees, since 1967. Recent Natural Capital initiatives such as Biodiversity Offsetting are in juxtaposition to these values and may unfortunately cancel them out. Any progress towards a landscape value would be hugely beneficial in keeping practitioners and people in their place at the forefront of policy making.

Thanks Cecilia.

I live in hope that our political leaders, such as they are, will begin to revisit – and relearn – the language of civic discourse rather than continue to spout endlessly meaningless corporate GroupSpeak.

I don’t know how the other reply snuck into this but, hey thanks Sigried! A translation would be terrific. I think the editor, David Maddox, and TNOC team would be happy to see the words being spread… Could you please be sure to include a link to the original blog?

Thanks Elliot. We really do have to push hard against the miasma of materialism that has enveloped the planet since the (relatively recent) hegemony of ‘free’ market advocates.

Thanks Elliot. We really do have to push hard against the miasma of materialism that has enveloped the planet since the (relatively recent) hegemony of ‘free’ market advocates.

Great article! I’d like to translate it to portuguese and help spreading the word…

Regards,

Sigried.

Rio de Metal

É Feito com Amor!

Great arguments Paul!

Thanks for making so clear how governance should focus on social-ecological values and relationships, not only on technological development and economic growth.

An excellent article. Hopefully we can get this thinking across to more people so that people understand social value as well as market value.