Nairobi is a bustling city of over 3 million people, many of whom are stuck in traffic for hours each day. One effort to mitigate these wasteful jams involves construction of additional motorways. But with little space specifically reserved for these new arteries, their proposed routes involve some delicate tradeoffs. One such road, the proposed Southern Bypass, is planned to run along the eastern boundary of Nairobi National Park. As presently designed, 150 acres of park land would need to be degazetted (i.e., lost) to accommodate the new road. Several nature conservation organizations have joined together to oppose the project, and a pending legal action has provisionally halted all construction.

In passing, one might understand this story as a tale of local conservation organizations banding together to “hold the line” — protecting a parcel of wilderness from the bulldozers of urban expansion. But in an urban system as complicated as Nairobi, context truly matters. Managing urban nature requires flexible and forward-looking perspectives, and I argue here that the issue is much more intricate than first meets the eye.

In fact, the project presents a rare opportunity, if leveraged aggressively, to expand and strengthen the integrity of Park while letting the Bypass go forward.

Nairobi National Park: a brief introduction

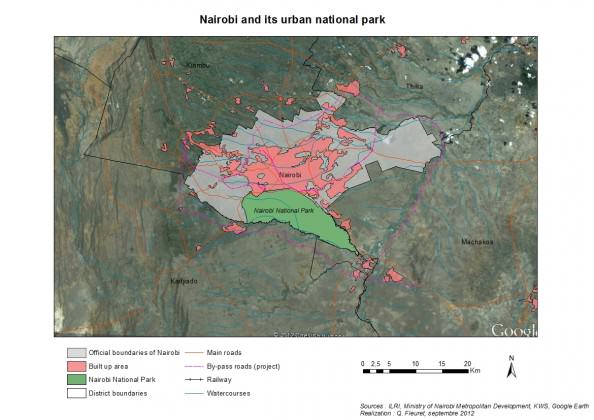

Situated just outside Kenya’s capital, the 117km² Nairobi National Park is a relatively small protected area (IUCN Category II). Managed by the Kenya Wildlife Service, this urban protected area is home to a wide range of wildlife, such as lion, leopard, cheetah, buffalo, giraffe, and the critically endangered black rhinoceros.

The formally protected area is itself an integral part of a 2000km² semi-arid savannah ecosystem, marked by characteristic seasonal wildlife migration from as far south as Tanzania. In the dry-season months of June to November, herbivores such as zebra and wildebeest take their annual refuge within park boundaries. From December, when rains return, this wildlife quickly disperses back to the open plains, where food will have become more plentiful and predators are more easily avoided.

Beyond serving as important habitat for wildlife, these plains south of Nairobi are also the traditional home of Maasai pastoralists, who have long adapted their practices to the natural rhythms of seasonal migration. For example, these herdsmen judiciously move away from migration routes at times when predators and calving wildlife posed risk to their cattle.

Back in 1946, when this national park was first established, these migrations were largely undisturbed by human activity. The city of Nairobi was much smaller then — about 120,000 residents — and the park was an unfenced wilderness somewhat beyond the urban horizon. Residential and industrial activity remained largely concentrated around Nairobi’s core, and a wide buffer remained between built-up and protected areas. Beyond the boundaries, with but little competition for land, wildlife, pastoralists, and city-dwellers all managed to live together.

However, Nairobi’s formerly modest urban center has now grown to a city of over 3 million inhabitants, and the functional distance between park and city has dramatically decreased. Residential development has progressively expanded against many of the park’s edges, including both informal townships and luxury accommodation.

Especially along the eastern boundary, heavy industrial activity like cement factories and an oil refinery contribute to a noxious environment where neither wildlife nor people can easily flourish. Clogged roadways now border the park on several sides, and works are underway to widen these to relieve congested traffic conditions.

Such intense urban activity just beside the national park has direct impacts for the health of this natural environment. Industrial and residential effluent require constant monitoring; windblown waste and illegal dumping pollute protected habitat; wildlife are increasingly killed along the heavily trafficked roads that now surround the park; while fence vandalism, illegal encroachment, and bush-meat poaching are other urban problems faced by park managers.

To separate the national park from the urban fabric, electric fences were progressively installed to the west, north, and east. Further reinforcing park boundaries, a public-private partnership called Nairobi GreenLine has been working to grow a 50m wide forest of native trees, along 30km of the park’s eastern edge.

As the initiative simple puts it: Nairobi National Park is Under Siege — It’s Time to Draw the Line.

It’s important to remember that the initial boundaries of the National Park were fixed by arbitrary conveniences such as a river, a road, and railway. Though only a small portion of the broader ecosystem was included for protection, seasonal wildlife movement was nonetheless able to continue precisely because of the strong connectivity between the park and its wildlife dispersal area. Explicitly for this purpose, the southern edge still retains an open border, allowing free movement of wildlife across the broader landscape. However, the growth of Nairobi shows no sign of slowing, and the long-term viability of these migrations is far from certain.

Fast-growing settlements of Rongai and Kitengela have respectively become established at the southeast and southwest corners of the park. Their persistent expansion continues to consume land that had previously been available for transiting wildlife. Similarly, land-speculation along the entire southern boundary is driving land-prices up, increasing the incentive for owners to subdivide. Over time, the park is slowly being encircled.

Because of the deep interdependence between the Nairobi National Park and the wildlife dispersal area to its south, a southern boundary fence would forever sever the protected area from its ecosystem. Though if privately built fences south of the park were to become sufficiently dense — as they seem on track to become — wildlife would similarly be inhibited from migrating, and the park would become totally isolated from the broader ecosystem it is supposed to support and protect.

In an attempt to preserve the needed migration corridors, several important efforts are ongoing. One initiative, known as the “Wildlife Lease Program” works to identify unprotected parcels of land most important for migration, and pays a nominal rent to the landowners in exchange for their commitment to neither subdivide, nor sell, nor fence the property. The lengthy waiting list of individuals that have applied to participate in the scheme is an indication both of this project’s potential, as well as just how much of the migration corridor remains unprotected.

A more general tool for preserving an unfenced landscape, the Kitengela-Isinya-Kipeto Land Use Management Plan is a community-developed planning regulation that restricts the minimum plot-size in much of the dispersal area. Here, the interests of the local community align with conservation aims, and collective efforts are underway to implement this scheme which simultaneously supports pastoral activity and wildlife migration.

While these and other efforts are laudable, urban pressures continue to increase the potential value of land this land south of the park – and the area remains especially and increasingly vulnerable to irreversible change.

On the importance of boundaries

In a sense, the 67-year history of Nairobi National Park can be summarized by two observations about its boundaries. First, the borders of this national park have proven to be a largely effective barrier to landuse change within the protected area. Spatial images illustrate this quite well: the unmistakable growth of urban Nairobi abruptly stops precisely where the national park begins.

Second, however, the area that was protected in 1946 doesn’t very well correspond to the most vulnerable places in 2013. This should not be surprising. After all, this was Kenya’s first protected area — and it was designated at a time when the scale of today’s Nairobi was simply unimaginable. As the capital has expanded — both in terms of its physical footprint and its indirect influence — the mismatch has become all the more consequential.

To secure permanent protection for ecosystem function in this rapidly evolving urban landscape – a reimagining is in order.

The Southern Bypass: a conservation threat?

Traffic congestion is a ubiquitous feature of daily life in Nairobi. Narrow roads are plied each day by an increasing number of private cars, heavy trucks, public busses and mini-van taxis. Crossing town can take hours — wasting human and energy resources, worsening air quality, and generally deteriorating the quality of urban life.

The Government of Kenya is mobilizing many resources to address this problem throughout the Nairobi metro region. These efforts include a network of so-called “bypass” roads, providing alternative routes to especially clogged arteries. One of these projects, the “Southern Bypass,” was approved in 2012 and will run parallel to the boundary of Nairobi National Park.

Under Kenyan law, this project required an Environmental Impact Assessment and a special license from the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA). A standard and unsurprising condition of this license is that “the proponent shall not encroach on gazetted parks,” specifically Nairobi National Park. However, this condition is being tested in two related respects.

First, over time, the land just beside Nairobi National Park has been occupied by a range of different residential and industrial land uses. While a narrow strip remains available for road construction, the proposed route is insufficiently wide. Second, in one specific place, the proposed road will run perpendicular to the runway of Nairobi’s domestic airport. There, flight safety regulations require more distance between the bypass than is presently available. Together, these reasons have obliged road engineers to design a route that at some points would traverse parts of Nairobi National Park. Accordingly, to comply with the conditions of the NEMA licence, the Kenyan Parliament would need to excise about 150 acres from the park. Local press reports that the loss would eventually be compensated by some 1.8 billion shillings (≈ US$21 million).

On the surface, transforming National Park land into a highway seems like a terrible outcome for nature. To stop this from happening, several local conservation organizations have begun legal proceedings at the National Environmental Tribunal, and indeed, construction has halted while the appeal is under review.

The main arguments of these organizations are as follows:

- The road would illegally encroach on the currently gazetted Nairobi National Park

- The project has become much larger than what was evaluated for the EIA

- The Kenya Wildlife Service has no mandate to negotiate the disposal of park land

- The integrity of national park boundaries must be respected, forever.

- Alternative means could allow road construction without traversing the National Park

- Degazetting park land would set a dangerous precedent and would damage Kenya’s reputation

- Land has already been allocated for a road; it must be reclaimed from other users.

Some of these arguments raise very important issues, especially the substantive questions about how the proposed transportation project is evolving on the ground. Others appear more tactical in nature, mobilizing political or procedural claims to prevent the proposed construction from going forward. Taken together, their unambiguous objective is to prevent Nairobi National Park from being harmed.

Of course, a vigilant and engaged civil society is an important part of conserving nature. With more and more people concentrated in cities, it is only natural that threats to urban protected areas are so vigorously resisted. However, these very same urban places are also subject to much more complex tradeoffs than wilderness settings would require. Such tradeoffs are politically delicate, but crucial for effective and adaptive stewardship of urban nature.

In this particular case, most arguments against the Southern Bypass also appear to be rooted in an absolute commitment to protecting the integrity of the park boundaries, no matter what. In light of the ever-growing threats that protected areas face, such a conservative position is often quite justified. But again, context truly matters — and maintaining pre-existing boundaries isn’t always the best deal for nature. Given how degraded certain sections of the park have become, how arbitrary the initial boundaries seem to have been, and the mismatch between the areas under protection and those essential for ecosystem function — if leveraged aggressively, this Southern Bypass could also be seen as a conservation opportunity.

The Southern Bypass: A Conservation Opportunity?

Like any policy, nature conservation does not and cannot exist in a vacuum. The hard reality is that, in many respects, the GreenLine initiative has it right: Nairobi National Park is under siege. Along the urban-facing edges, negative impacts are increasingly degrading the protected habitat; and along the southern boundary, if the status quo persists, growing pressure from an expanding city will totally isolate this protected area from its natural ecosystem. Though the current park boundaries are fairly effective at preventing land use change within them — the surrounding landscape is evolving in ways that undermine the sense of that protection.

When viewed in this way, the proposed Southern Bypass should be seen not only as a threat to the National Park — but also as a multifaceted opportunity.

Remaining focused for a moment on the narrow strip of land that might be excised: the traffic congestion in Nairobi truly is dire, and resolving this problem is a top urban priority. With virtually no alternative routes available, this land along the Nairobi National Park boundary is tremendously valuable. It is a true asset, which can shrewdly be leveraged to support the park’s overall conservation.

Looking more broadly at edge conditions, decades of relaxed planning regulation seem to have allowed areas beside the National Park to be occupied by a land uses that are entirely inappropriate neighbors for a protected area. The negative impacts they cause are in some cases so severe that neither wildlife nor people are able to occupy the areas. With no real hope of moving these industries away from the park, one viable solution for better edge protection is to create a new buffer from existing park land. In some places, the forest proposed by Nairobi GreenLine is an example of how this is being done. In other sections, it’s worth asking whether and how an appropriately built roadway could serve a similar function.

Unsurprisingly, the land within protected area boundaries is often coveted for other uses, and this is not the kind of tradeoff to be made lightly. Decisions should be informed by the best available science, and in case of doubt over the conservation value of affected areas, the precautionary principle should prevail. But if it turns out such a bargain would yield significant, permanent gains for conservation it would be foolish to dismiss the opportunity out of hand.

From a landscape perspective, the most pressing threat to Nairobi National Park does not really depend on the exact location of its northern boundaries. Rather, the future of this protected area hinges instead on how the area south to its south will develop. As it looks now, the prognosis is fairly bleak.

In this light, the real opportunity of the Southern Bypass is to reimagine the size and shape of Nairobi National Park — expanding its protection to the most vulnerable places, thanks to the value of some its most degraded parcels.

In so rapidly changing an urban setting — where events are quickly overtaking the existing conservation geography — what sense does it really make to tightly preserve the precise locations of historical park boundaries? By virtue of the resources available for constructing this road infrastructure, the proposed Southern Bypass offers a rare opportunity to broadly renegotiate the form and function of Nairobi National Park. This opportunity should be seized, and the net gains for conservation should be measured not in terms of individual parcels, but rather, in terms of long-term ecosystem function.

- How broad a migration corridor would need protection to permanently facilitate seasonal wildlife movement?

- What other benefits would this protection have for the practice of traditional pastoralism in the dispersal area?

- Would such gains make for a worthwhile tradeoff?

For the future health of Nairobi National Park — and by extension, the wellbeing of all Nairobians — I’d strongly suggest that such questions are worth considering.

Glen Hyman

Paris

Leave a Reply