How can we measure the ways in which we perceive, are affected by, act and reflect on the nature of the city? The human body is a sensor-motor apparatus within a mutually moving nature-culture continuum. This sensori-motor apparatus has a vast capability of quickly evaluating vast amounts of information and acting on it while new technologies continue to extend human perception.

Remote sensing from satellites, airplanes and drones has replaced the cadastral survey from the ground, extending the body’s earth bound senses with continuous data from above. GIS has become the dominant mode of accurate measurement of spatial data, but cinematic, video and now smart phone eye-level camera views are almost universally employed to describe the qualitative feeling of a particular place at a specific point in time. Camera toting vehicles from Google roam the earth with the promise of integrating the map and street view into one tool. Satellites are now connected to the global positioning of our smart phones, combining both portable maps and cameras, and putting data gathering, mapping, filming and viewing in the hands of millions of people.

Crowd sourcing this data has a great potential to inform us about how humans behave within earth’s nature-culture continuum, if only we had ways of filtering and understanding this avalanche of information.

New tools are needed in order to understand the interconnectedness of nature and culture, where neither is fixed in space or time. Specific disciplinary tools such as those developed separately in the fields of cognitive science, architecture, film and ecology can be combined in order to find common knowledge among different ways of thinking and practicing and to connect quantitative and qualitative research.

This post introduces the concept of the sensori-motor city as a methodology to call attention to human perception, affection, action and reflection as discrete sets of information within the informational overload of the nature-culture continuum. Rushing by at twenty-four frames per second, a single film frame is an instantaneous slice of perception within the illusion of cinematic continuity. Frozen as an immobile cut, a film frame can be mined for information and measured as an instance of space/time.

The workshops presented here are examples of design-based research combining architecture and film techniques situated between cognitive and ecological science. While both sciences seek to measure complex systems, architecture and film exists in the space between perceiving, sensing beings and a world of constant flux. Human attention when directed towards understanding our selves as decisive agents within an environment in flux can lead to engaged sustainable design practices.

This blog post describes sensori-motor exercises that have made us more aware of how we perceive and act in the world, how we make choices and how we behave. The ability to measure the human sensori-motor system will inform more effective design strageties to connect rather than separate culture from nature.

Film frames as data on moments of the nature-culture continuum

The book Cinemetrics introduces the camera as a tool through which framed sets of information can be measured as immobile cuts through the continuous movement of matter in flux. Exercises from the book utilize film theory in order to understand human cognition and behavior in relation to architectural space and environmental stimulus. The workings of the human sensori-motor system can be understood through a frame-by-frame mapping of film sequences in order to draw attention to how we perceive the world through our senses, how our body is affected by those perceptions, how we act on those feelings, sometimes on impulse, and how we reflect on the consequence of those actions. By stopping the world through framed infomatic sets, we are able to relate perceptions and feelings to actions and learn to recognize impulsive behavior over time. Framed information from the ground can be aggregated to produce clouds of data informing socio-ecological science.

The architecture of cities extends the human sensori-motor system. Cities provide comfort, nourishment and pleasure. We need to tools to continue to adapt cities for that purpose while also measuring the environmental impacts of human behavior—the ecology of the city. The sensori-motor city is an idea of directing the human sensori-motor system towards sharper attentiveness and reflective action through careful analysis of film frames as sets of information, or individual pieces of data. The sensori-motor city is introduced here through a series of videos recorded during three undergraduate student workshops over the past year at National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan, Parsons The New School for Design in New York and Chu Hai College of Higher Education in Hong Kong. Concepts and examples from Cinemetrics were put into practice through performance, video and drawing exercises.

All the workshops employ three brief film sequences to measure, frame-by-frame, how the human sensori-motor apparatus continually reframes perceptions, affections, impulses, actions, reflections and relations as immobile instances through the fluidity of the nature-culture continuum of urban life. First, students in the design studios of National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan reenacted scenes from three movies, each with a unique filming method. Second, the students performed these scenes in the limited confines of a 3 x 6 meter space in the Taipei. Here the cultural differences between the three film directors became understood by comparative measurement. Thirdly, the film scene reenactments were performed in slow motion in the Aronson 5th Avenue storefront Gallery at Parsons The New School for Design in New York as part of a hand-drawing workshop. Machines were constructed to allow the hand drawing style to follow the method of filming of each film director. Finally, these drawing machines were recreated in order to record and measure ordinary human movement on site in Tsuen Wan New Town, Hong Kong. Based on this research, we call for new tools to understand cities as social and physical extensions of the sensori-motor system as the first step in making cities more sensitive and systemic and therefore more humane and sustainable.

The workshops are centered around three short film sequences from domestic scenes taking place in Tokyo (Yasujiro Ozu’s Early Spring 1956), Rome (Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt 1963) and Los Angeles (John Cassavetes Faces 1968). Domestic scenes are ways of seeing cities from the inside out. All films take the viewer from the interior of the house to the larger natural-cultural changes that the microcosm of domestic life serves to represent. Since the students who participated in the Taiwan workshop were born nearly three decades after the making of these three films, their performance of the three film sequences offered them cross-cultural and historical insight into the emergence of the mediated consumer culture that came to dominate the world of global modernization they were born into. The lesson we all learned through the workshop was not just how to use film techniques to measure urban spatial experience, but also how the human sensori-motor system is transmitted and affected by media. Performing the roles of a husband and wife in Tokyo, Rome and Los Angeles generated lessons in empathy, for both the student-actors, audience participants and the general audience, as well as in measuring the social production on space in different cultural contexts.

Ozu’s films set during Japan’s post-war economic boom were made as entertaining melodramas appealing to the tastes of women living through an exceptional shift in domestic life during the 1950’s. The drama of Early Spring follows a young wife’s struggle to maintain the rituals of a traditional household while her husband, a new breed of white-collar salary man, succumbs to the boredom of modern commuting life. While Masako, the wife, dutifully performs traditional mourning rites for their deceased child, Shoji, the husband enters into a brief affair with an office co-worker. The film continuously “commutes” between the couple’s home and the husband’s office, and the in-between third spaces that constitute the rich social life of the city. Watching Early Spring, like many of Ozu’s films, we witness the huge social mutation of modernity from a small-scale domestic point of view, where the wife’s traditional sense of duty and devotion prevails in the end.

Godard’s Rome of 1963 is similarly caught in the post-war dynamics of an economic boom, but from a European socio-political perspective. The three-scene movie begins and ends on film sets of a Hollywood spectacle, and in between is the domestic scene where the married couple bathes and dresses to go out to watch a movie. The opening scene takes place in Cinecitta, the film studios built by Mussolini. In the film a Hollywood production of the classical Greek tragedy of Odyssey is dictated over by the fascist-like American film producer. The last scene of the film is a staged film shoot that takes place on the roof of Casa Malaparte overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. The pivotal domestic scene at the heart of the movie is filmed in a modern new condominium outside Rome. The apartment is the dream home of the married couple, the writer, and the former secretary, paid for by the writer selling is talents to rewrite the Greek tragedy for a Hollywood audience. Fritz Lang has a cameo role as the hapless European film director dominated by the commercial interests of the American producer. The couple’s struggles mirror Fritz Lang’s in that their dreams are now dictated by a new American hegemony, which came to dominate Europe following World War II. Contempt, Godard’s only Hollywood financed movie, expresses the director’s own dilemma in creating a work of art when film is in fact had become an industrial product. Godard’s critique of the new dominance of American consumer culture is situated dramatically here in Rome as the cross Atlantic natural-cultural continuum replaced the classical Mediterranean world.

Cassavetes takes us to the capital of this new empire of the Hollywood spectacle: Los Angeles, 1968, a most auspicious year for societal breakdown. Here we are in the decadent heart of the mid-20th century American consumerism, as the husband Richard is a prosperous movie producer as well, with a car, a beautiful wife, Maria, and a large home in the hills above Hollywood. Richard, like Greek-American Cassavetes, is living the “American Dream.” Cassavetes, however, remained outside the Hollywood studio system, as his films were deemed too experimental. He financed his films independently through his own acting career in Hollywood films, and relied on his wife, family and friends to act in is movies. Faces was shot in his own home he shared with his wife and star of many of his films, Gena Rowlands, who plays Richard’s mistress Jeannie in Faces. For Cassavetes and his ensemble of actors, the American dream was portrayed in fact as a nightmare of unrestrained and uninhibited impulse.

Performing these three sequences helped us to understand how the cities in which these films are located could be understood through measuring and comparing the embodied habitation of each. Additionally, while each of the three directors filmed a husband and wife in domestic routines, the film style shifts radically—from stationary and meditative to slowly moving and geometric to impulsive and dynamic. With industrialization and modernization, cities are often blamed for both human and environmental “breakdowns.” These workshops help students understand how sensori-motor breakdowns are, in fact, part of a feedback loop between human perceptions, feelings and actions in culturally constructed urban environments. The exercises provide the source for new ways of thinking and living within the mutual movement of nature and culture. Performing the three film scenes generated embodied empathetic knowledge of the breaking points and blind spots of consumer culture. This embodied knowledge came from inhabiting media as well as the globalized space of an international workshop and expositions.

Additionally each film director has a distinct way of framing the nature-culture continuum. Ozu patiently portrayed the social mutation of post-war Tokyo by framing separate shots that illustrate the basic movements of sensori-motor system: perception, action and affection images respectively as long, medium and close-up shots. Godard scans European culture under assault in the banality of American style consumer culture with a slowly moving yet monumentally framed cinemascope camera. Cassavetes exhausts these movements and assembles a montage of bodies experiencing physical and psychological breakdowns with his innovation of the hand-held camera.

Ozu, Godard and Cassavetes not only provide clear examples of the human sensori-motor system, but they are exemplary of the new direction in film following World War II that is inhabited by bodies that do not know how to sense, feel or act [see Note 1 at the end of this essay]. Cassavetes and Godard’s films end as Ozu’s starts – as pure optical and sound image beyond the endless cycle of perception, affections and action. After a sensori-motor breakdown, inventing the new ways of perceiving, feeling and acting within the nature-culture continuum becomes possible.

Measuring the Sensori-motor City

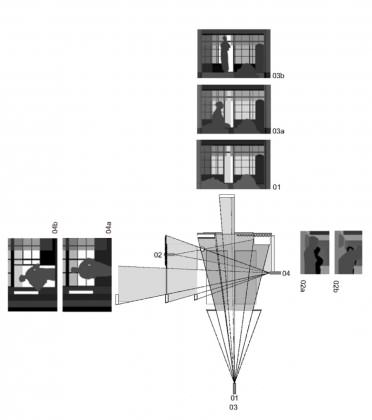

The first workshop in Taiwan involved the students rehearsing the three film scenes in order to perform in a 3 x 6 meter space in the Tapei World Design Expo. The directive of the workshop was to match as closely as possible the original film within the spatial limits of the Taipei World Design Expo venue, and to consider how to attract an audience to the performance. Yasujiro Ozu filmed Early Spring in a sound stage in Tokyo. The set for the domestic scene depicts a modest working class home with sliding shoji screens, tatami mats, and several neighbors’ homes located directly across a narrow alley. The scenes’ separate shots are staged as composed tableau-like theater sets, precisely filmed at right angles.

The setting of the Early Spring’s opening scene easily fit within the 3 x 6 meter Expo booth space. The challenged faced by the Ozu student team [Note 2] in performing this three minute sequence was not one of spatial limitation as the film is a vivid depiction of the frugal and efficient use of space in Japanese tradition. Rather, the challenge was in representing the multiple angled cuts within the three-minute sequence to the audience. Should the live audience remain stable like in the theater, or be encouraged to walk around the performance in order to understand the shifting camera position? Both the 90-degree camera rotation, and altering distance from the performance were critical to Ozu’s film making technique.

Rehearsal of the opening sequence of Ozu’s Early Spring:

The Ozu team constructed a portable set which conveyed the bedroom scene, while at the same time revealing the shifting vantage points from which the scene was shot by constructing framed openings. Students took on various roles, actors, timekeeper, scenery, stage blocking, and director. The audience was not only encouraged to walk around the set in order to understand the multiple camera positions employed by Ozu, but also were given scripts to perform a role in the scene itself. Ozu’s method of matching is cuts precisely within an actors movement, for instance the wife and husband getting up in bed, is performed in stop-motion by the student and audience actors, in order to shift the camera viewing position with the actor’s body motion.

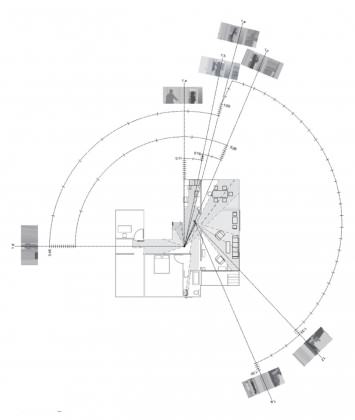

While Ozu shot his film in a sound studio—his framed “set of information” is literally a constructed set—Godard carefully selects and arranges the settings for his films from scouted locations. The modern apartment at the heart of the film is an “art directed” set, carefully arranged to mimic the incompleteness and barrenness of the couple’s marriage. Godard’s filming style of the domestic sequence is a remarkable example of long, uncut sequences. The panning camera frames a variation in subject distance similar to Ozu’s long-shot perception image, medium shot action image and close-up affections, but in Contempt the images are continually unfolding in time rather than separated by discrete edited cuts. The camera slowly pans, while the actors are moving about often in opposite directions creating a complex choreography of image variation.

Rehearsal of sequence from Godard’s Contempt where the students measure the movement of actors, camera and props by tracing their footprints:

The task of the Godard student team [Note 3] both revealed the difficulty of matching the syncopated movements of the actors and the camera, but also the dimensional fact that the spacious Roman flat that Godard chose for the pivotal domestic scene of the movie extends far beyond the 3 x 6 meter exhibition booth at the Taipei World Design Expo. The student team therefore developed a system of moving the background scenery, along with the performing actors, in order to give the illusion of an elongated set as viewed by the centrally placed panning camera. The team also developed a method of recording the changing positions of the actors, set assistants and cinematographer, by dipping hand made sandals in color-coded paint during rehearsal, producing a footprint map of the performance. In the final performance the team coated the black floor of the Design Expo booth with white flour, leaving traces during the performance like footsteps in snow.

Godard performance as part of an exhibit at the Taipei World Design Forum:

Cassavetes filmed the domestic scenes of Faces in his own home in Los Angeles. Filled among the ordinary mess of domestic paraphernalia rather than a sound stage or an art-directed set, the film takes on another level of immediacy and reality. The scale of Cassavetes’ large two-story home presented a considerable challenge for the NCKU team [Note 4] Their task was to present the final scene of the movie where the husband runs up stairs and chases his rival outside and over the garage roof within the same 3 x 6 meter space in the Taipei Expo. The action quickly travels through the two-story extent of the house captured by Cassavetes’ hand-held camera. By focusing on the information within the constantly moving camera frame rather than the spatial extent of the house depicted, the student team was able to create the illusion of a two-story house chase scene within the 3 x 6 meter Design Expo booth. After numerous trials and errors in rehearsal, the team concocted a way of suspending an actor performing the role of the husband horizontally across a moving backdrop of a painted stairway. By turning the plan view of the camera to an elevation, the team created the illusion of the shot in which Cassavetes film Richard running up the staircase from above, thereby compressing a large two-story American home into a small exhibition booth.

Rehearsal of sequence from the final scene of Cassavetes’ Faces:

http://youtu.be/P4CH5MYq10s

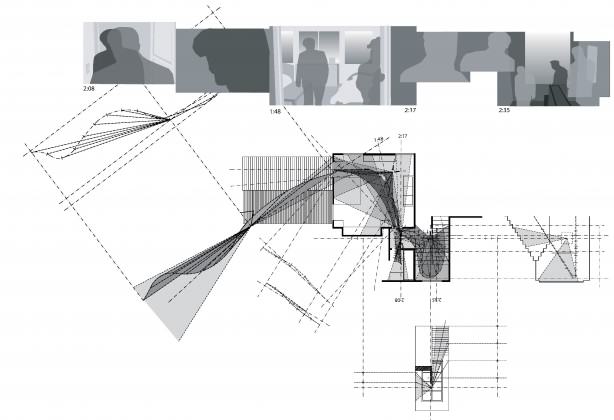

New York Drawing Workshop: Slow Motion

The Drawing Lab, led by Jose DeJesus at Parsons The New School for Design, transformed the School’s Aronson Gallery into a three-dimensional data mining and drawing apparatus. The installation accumulates works made by the public: free-hand drawing, photo and video, spatial diagramming and measurement, textual performance and language play—all cinemetric tools of the Drawing Lab.

The Taiwan performances were repeated in slow motion in order to allow for simultaneous drawing of the movement of the actors. Jose DeJesus designed and constructed “drawing machines” that matched the camera technique of each director. Each film sequence was mapped and measured on the gallery floor with colored tape: black for Ozu (still camera in seated position), red for Godard (panning camera in standing eye-level position), and yellow for Cassavetes (hand-held camera). The students could measure not only different ways of “acting” in the world, but also different was of framing the mutual movement of nature-culture.

Drawing the Ozu performance:

Drawing the Godard performance:

Measuring the Cassavetes performance with tape on the gallery floor:

http://youtu.be/JxpE49Ww4Lw

Finally, in March 2013, at Chu Hai College of Higher Education in Hong Kong, students and faculty from Chu Hai, Parsons, NCKU, and Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, Thailand participated in a workshop [Note 5]. The workshop topic was how to recycle the older “New Towns” in Hong Kong, now that factories have been relocated to China, commercial spaces have been left vacant as shopper prefer the malls in central Hong Kong, and the majority of residents are aging in place. Furthermore, the question of the nature-culture continuum is particularly extreme in Hong Kong, as the city has been planned to reserve 65% of the territory as protected natural areas, while most of the city consists of high-rise residential enclaves built on top of podiums. Here students filmed the everyday movements of the New Town residents, and then placed the cinemetric drawing machines in situ in and performed the movements they recorded.

Godard drawing machine in Tsuen Wan New Town, Hong Kong:

This latest step in our collaborative research brought us closer to our aspiration of utilizing sensori-motor tools for participatory urban ecosystem design: first, by making clear how we perceive, are affected by and act in the world, and then how to reflect and relate our actions towards natural-cultural transformations. Measuring the sensori-motor system brings attention to sight, hearing and kinesthetics in relation to environmental change.

Further explorations include smell, taste and touch—all absent when graphically analyzing film frames, but present to participants performing in the workshops. In our last exercise in Hong Kong, by brining the drawing machines into an urban space, we created new ways of sensing and acting within the nature-culture continuum. Fundamentally, Cinemetrics instills the knowledge that we change the environment by first changing our perceptions, our actions and ourselves through reflective feedback and relational behavior.

Brian McGrath, Jose DeJesus, Jean Gardner, Victoria Marshall, Anthony Deen, Alaiyo Bradshaw

New York

Hsueh Cheng-Luen

Tainan

Eugenia Vidal

Bangkok

Paul Chu, Stan Lai, Santefe Poon

Hong Kong

Note 1: Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image (L’Image-temps, Cinéma 2, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1985), translated by Hugh Tomlinson, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Note 2: Taiwan Ozu student team: Li Yu-Ting, Lai Szu-Yu, Lou Li-Wan, Liu Sz-Hui, Kornpong Nualsanit, Nuthapong Jiratiticharoen, Pornprapa Rugwongprayoon, Andrea Louise Brondsted, Wuttiphon Rattanajitdamrong, Hsu Wen-Hsiang, Wang Shin-Yu, Wu Ping-Jung

Note 3: Taiwan Godard student team: Cheng Chi-Ying, Wang Po-Hao, Huang Yi-Chen, Napakaporn Buatong, Kasidej Pat Anantaphongs, Veerasu Saetae, Pitchapa Jular, Joann Mari Glorioso Busk, Natreeya Kraichitti, Huang Wan-Yun, Cai Tsung-Han, Wang Chia-Ping, Cheng Yu-Wen

Note 4: Taiwan Cassavetes student team: Lin Jin-Jing, Wong Lii Tyng Irene, Hsu Kuo-Feng, Benjawan Iamsa-ard, Chayongkul Green Tavitavonsawas, Arnut Areechitsakul, Sumana Amatayakul, Carina Dannemand Sorensen, Cheng Chu-Yun, Lu Ching-Yi, Tseng Shiao-Yun, Yang Han-Lin, Wuu Hsih-Shin, Lin Wan-Hsuan

Note 5: “New Towns in Hong Kong team: Au Yeung Kin Sum, Yeung Yuen Wing, Le Donghui, Cham Wai Lok, Tam Kit On, Chang Chien, I-Hsin, Supanut Bunjaratravee, Nut, Wong On Yee, Wong Shuk Man Joyce, Wong Chun Lung, Suen Tin Yat Gary, Tse Pak Wing, Tseng, Yen-Fang, Wongsakorn Wattanavekin, Tee, Chiu Mei Ying, Leung Wai Lap, Wong Wing Man, Ko Wing Kit, Liu Ho Yin, Leung Lok Ming, Hong Jihee, Apisub Phupha, Non, Lie Cheuk Lam, Tse Chi Man, Lam Ho, Chan Cham Kwan, Lam Ho Wing Owen, Yip Wing Yee, So Chun Pong, Lee Ka Chon, Chan Tsz Wai, Ho Yee Ting, Cheung Ming Hin, Zhou Ying, Kwok Yip Wai, Tong Wai Kin, Kong Pui Sze, Chiu, Wei-Chih, Panachai Chankrachang, Yee Ho Yin, Han Sarang, Changlum Chayatip, Thanaphon Morakotwichitkarn, Mark, Chang, Bor-Min, Nichakamol Horungruang, Bung, Lau Chung Ming, Wong King Fai, Zhang Tong, Ho Ho Pong, Poon Iu Tung, Lee Ji Won, Lai, Hung-Yi, Cho Fai, Ho Hoi Kee, Kwok Tung Kiu, Chan Yin Shan, Wong Hoi Lam, Wong Yan Ho, Jung Hee Joon, Kao, Yuan-Tse, Chow Wang Fung, Leung Man Ching, Wong Wai Yee, Fang Ruiyao, Suwanparin Nole, Lopez Jessica, Chan Cho Man, Sin Timothy, Wang Shaoyi, Chan Po Yi, Tse Ching Ho Dax, Chang, Hsiao-Mei, Bahnfun Chittmittrapap, Dream

Leave a Reply