I admit it, I’m obsessed with a small created wetland in NW Portland’s Pearl District. When it comes to urban greenspaces size is often overrated, meaning even a small created 200 x 200 foot faux wetlands can be both biologically and socially meaningful in intensely development urban neighborhoods. Tanner Springs is one of those sites.

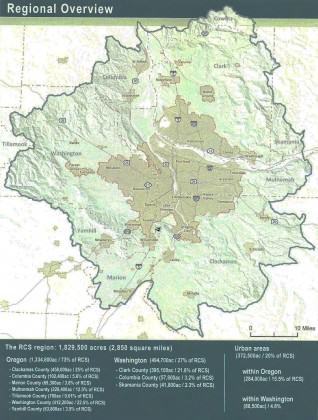

In my last piece, Biodiversity Planning: Finally Getting It Right In the Portland-Vancouver Metro Region, I described The Intertwine Alliance’s newly released Regional Conservation Strategy and Biodiversity Guide for the Greater Portland-Vancouver Region that will allow our region to prioritize areas of high conservation value across the 3,000 square mile urban-rural continuum. These products are a vast improvement over past efforts to map fish and wildlife habitat and areas of special ecological concern. One of the most important features of the new mapping was its five meter pixel resolution that is intended to assist park and natural area planners and restoration ecologists to prioritize their work at every scale, from the 3,000-square mile landscape to individual neighborhoods and the streetscape.

Over the past thirty years we have made impressive strides in the city of Portland and the urbanizing Portland-Vancouver region with regard to protecting large natural areas such as 5,000-acre Forest Park, 800-acre Powell Butte Nature Park and other large natural areas within and just outside the region’s Urban Growth Boundary.

On the acquisition side, we have passed two bond measures totaling $363 million with which our regional government, Metro, and local park providers have added thousands of acres of natural areas to the public land base. Most of those acquisitions, however, have been sites of several hundred to more than 1,000 acres. Another significant recent success was the recent passage of the region’s first ever natural areas management and restoration levy, a $50 million five year funding source that will provide Metro with funds to manage is 16,000 acres of natural areas.

While these accomplishments contribute mightily to the region’s efforts to protect biodiversity across the regional landscape, what of the small, interstitial greenspaces, the left over bits of nature that play an oversized role in providing access to nature in the everyday lives of urban dwellers? They have historically been overlooked, undervalued, and viewed as throw away habitats, discarded in the name of “compact urban form.” If we hope to create livable and lovable cities where urbanites have access to nature where they live, work and play our next big challenge is protecting, restoring and, where necessary, designing and creating, small but ecologically and socially significant patches of urban greenspace. Without diminishing the importance of large “anchor” habitats in maintaining biodiversity, the scraps and threads of urban greenspaces that provide connectivity throughout the city and into the surrounding rural landscape are equally important. Size matters alright…at every scale, from the streetscape to large regionally significant nature preserves.

What these small pieces, embedded in the urban matrix, lack in biodiversity they often matter most vis a vis their proximity to the majority of urban residents and ensuring people have access to nature—often in more dramatic ways than a wilderness experience. This is especially true in park and nature deficient neighborhoods. One expects to see an osprey land a fish in the Columbia or Willamette River in Portland.

But, when an osprey snags a koi ten feet away from a shallow pond or a great blue heron walks through a created wetland in one of the city’s densest neighborhoods it’s a transformational experience for a five-year old. It’s possible to design such experiences into the urban landscape, in even the smallest parks and natural areas.

Creating wild in the city: Portland’s park triptych

A triptych is a work of art that is divided into three sections, or three carved panels which are hinged together and can be folded shut or displayed open. Something composed or presented in three parts or sections; three canvases forming one image.

With the recent dedication of The Fields park a new work of art, a park triptych, was unveiled in Portland’s Pearl District.

The Fields, an expansive greensward, is the third in a series of parks in one of Portland’s densest neighborhoods, The Pearl District. The other two parks, the hardscaped water park at Jamison Square and the faux wetlands and spring of Tanner Springs Nature Park were dedicated in 2002 and 2005 respectively. Each park represents a unique urban design serving widely divergent, but complementary functions.

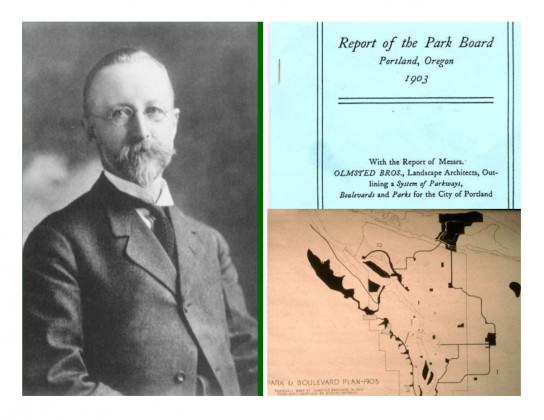

In June 1999, Peter Walker & Partners landscape architects provided Portland Parks and Recreation concepts for three new parks that have become critical to the success of what has been a dramatic transformation of an industrial and manufacturing center and transportation hub of rail yards to a new high density, mixed use neighborhood with multi-family residences, offices, and commercial development. What I admire most about these parks is that their designs reflect the philosophy espoused by landscape architect John Charles Olmsted in his 1903 master plan for Portland, which called for the creation of a comprehensive, interconnected park system.

Olmsted developed a park typology, from urban squares that would function as public gathering places to large scenic reservations like Forest Park. Walker’s vision for the Pearl District included three parks that would serve specific functions and be knitted together with an ipe wood boardwalk.

Jamison Square Park, the first to be developed, was named to honor William Jamison, art gallery owner and early advocate for the Pearl District. The park’s main feature is a fountain with a shallow wading pool that ebbs and flows throughout the day. On a regular basis water flows between and over a rock wall, filling a shallow basin. What was conceived of as a neighborhood park has, in fact, become a regional attraction. On a hot summer day there may be several hundred children and their parents playing in the water or lounging under the birch trees.

The Fields, a large grassy ellipse three blocks north of Jamison Square, was designed for kite flying, throwing Frisbees, sunbathing, and other informal recreation. The park features an off-lease dog area, rain garden, and children’s play area.

Tanner Springs Park

A couple years ago I was driving north, adjacent to Tanner Springs Park, when a black and white blur flashed across my windshield. I looked to my right and a woman stood, mouth agape. She’d clearly seen the same thing I had. As I jumped out of my car an Osprey arose from the park’s shallow pond, a koi clutched in its talons.

It carried its prey to the roof of a nearby condominium and consumed the tiny koi after which it returned to its nest on the nearby Willamette River. I asked the woman whether this was unusual and she replied no, that it had become fairly common since someone in the surrounding condos had, illegally, started dumping koi in the pond. She provided me with a photo of the osprey which I immediately sent to Herbert Dreiseitl at Atelier Dreiseitl in Germany and Mike Faha, at Portland’s GreenWorks landscape architects who collaborated on Tanner Springs design to inform them that they had just been paid the highest praise for their design work. Great blue herons, too, visit Tanner Springs Park, attracted by koi. Great Blue Herons also frequent the nearby Chinese Garden in old town Portland.

What was once a stream, a natural wetland, and lake system in the Willamette River floodplain is now a native plant-dominated one-square block nature park. What’s amazing about this small urban greenspaces is the wildlife it has attracted into the newly created Pearl District. The original plan for the park was to daylight Tanner Creek. That turned out to be impractical, given the stream now flows more than twenty feet below the park. The Dreiseitl/GreenWorks design was developed from several charettes that were conducted in 2003 that revealed the public’s desire to have a water feature and access to nature in the city.

An “artwall” runs along the east edge of the park consisting of 368 railroad tracks set on end with almost one-hundred blue “Bulls Eye” fused glass which was produced by a Portland glass art company. Each of the rectangular glass panels has images of dragonflies, and other aquatic invertebrates native to local wetlands. The images were hand-painted by Herbert Dreiseitl directly onto the glass panel, which was then fused and melted and inset into the tracks. One of Dreisitl’s panels is dedicated to the “lost wetlands” the park is intended to evoke. The New York Times ran a piece on Tanner Springs, describing it as “a sort of cross between an Italian piazza and a weedy urban wetland with lots of benches perched besides gently running streams.” Tanner Springs also provides a quiet, contemplative space for tenant in the nearby Sitka Apartments, an affordable housing project that sits catty-corner to the park.

Heron Pointe Wetlands

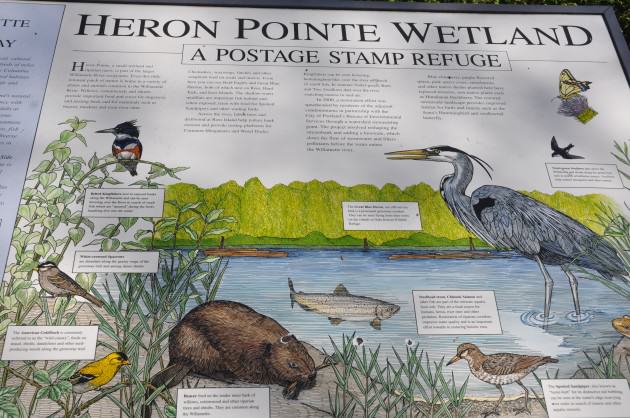

While Tanner Springs represents an example of created nature, a second small wetland is a case study in the preservation and restoration of a less than one-acre wetland on the west banks of the Willamette River. In 1984 the Heron Pointe condominium development proposal would have filled the postage stamp wetland.

The argument used to request the wetland fill was one all too often invoked when developers seek wetland fill permits—the site was so small that it had little ecological value and that nearby Ross Island complex was more significant. After a protracted fight the wetland was retained as an amenity to the adjacent condominiums.

Today, not only has the wetland been restored in a cooperative effort with the home owners association and city’s Bureau of Environmental Services and Park Bureau, but it is one of very few refugia for Chinook salmon and steelhead trout, both of which are now listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. While it’s true that, compared with nearby 350-acre Ross Island complex the wetland is comparatively unimportant from a region’s biodiversity perspective, it serves as one of only two sites for the local neighborhood.

In the end, small seemingly unimportant areas like Heron Pointe are treasured by local residents not for their contribution to the city’s biodiversity, but because they bring wildlife to their very doorstep. We installed an interpretive sign twenty years ago which we situated next to the Willamette Greenway Trail that sees hundreds of people daily on their commute or walking and cycling the greenway on weekend outings.

Nothing represents the neighborhood’s attachment to this small scrap of wetland more than the tiny bronze beaver that was installed by a local resident in memory of her husband who succumbed to Alzheimer’s. More often than not passersby leave a little memento with the beaver, sometimes a beaver-chewed stick others a more whimsical gift of flowers or other memorabilia. The beaver’s head is worn smooth from the many pats on the head it receives from walkers on the adjacent Willamette River Greenway path.

Mike Houck

Portland, Oregon USA

Leave a Reply