What we choose to name and the names we choose to remember, for the places, people and things around us, says a great deal about what is important to us. It is commonly said, and accurately so I believe, that we will not care about what we do not recognize.

That we increasingly lack the ability to recognize and name the common species and plants and animals around us is commonly acknowledged. My own work confirms this, as for several years we administered a “what is this” slideshow to my students that generated disappointing outcomes. Very common species of birds, trees, and plants went largely unrecognized. Only a handful were able to recognize a silver-spotted skipper, a very common and visually distinctive butterfly, but many proclaimed it to be a Monarch butterfly (which I came to conclude was virtually the only species of butterfly that Americans seem to know, if incorrectly, and can come up with).

Native Virginians taking my visual survey had a hard time recognizing their state insect (only a handful could), the visually spectacular and quite distinctive eastern tiger swallowtail, and only a few could identify the female of our state bird, the cardinal (not the bright red of the male that most everyone knows). What’s important is not that the images are of species that are in some way “official” flora or fauna, but that they are so common. These students had a good chance of having seen these animals on the way to the class in which they took this quiz. While many respondents (they were largely students) generally didn’t do very well in recognizing the plants and animals, they were themselves sweetly alarmed at this. On the answer form I had a number of students express some sense of being sorry or being disappointed in themselves for not being able to recognize these images. I had comments like “I’m embarrassed about how few birds I can identify,” and “I’m sorry, I just don’t know.” There was not a blasé attitude about this, but, encouragingly, a sense of genuine concern about how they fared on this unusual test.

Other studies have reached similar conclusions about our limited ability to identify common species of flora and fauna (e.g. Cassidy, 2008). Andrew Balmford and his colleagues at Cambridge famously designed a flashcard experiment that found children much better able to identify Pokémon characters than native species of plants and animals, leading them to conclude: “it appears that conservationists are doing less well than the creators of Pokémon at inspiring interest in their subjects: during their primary school years, children apparently learn far more about Pokémon than about their native wildlife and enter secondary school being able to name less than 50% of common wildlife types” (Balmford, et al, 2002). “People care about what they know,” Balmford et al conclude, something I agree, and these findings do not bode well for future conservation, urban or otherwise.

Perhaps this paucity of natural history knowledge is just a symptom of the times, of our profound disconnect from place, land, history. Our knowledge of the natural environments and landscapes in which we live is limited to nil and our direct experience of it ever more infrequent. We have limited understanding of where and how food is produced, how and from where water and energy arrive at our homes, and little sense of where the many wastes that we generate end up. We buy houses and make real estate investments, but we don’t join communities or neighborhoods. We don’t understand ourselves as creatures of actual places, embedded within and caring about landscapes and communities, but rather as temporary occupants, in a kind of ephemeral “holding in place pattern”, with seemingly little interest in or commitment to where we actually are. Contemporary American culture makes deep understanding of actual places and the people and nature that inhabit them difficult, to be sure. Children seem especially disconnected today, suffering from what Richard Louv has termed “nature-deficit disorder.” Kids today are more likely to know about African elephants or Bengel tigers than local flora and fauna, and better able, moreover, to recognize the ubiquitous corporate symbols (McDonalds, or Target) than an indigenous species of dragonfly or wildflower (I have written extensively elsewhere about this trend in Beatley, 2005).

Similarly, other forms of local knowledge seem supplanted by the more generic, the more general, the globalized and universal. Few here in Central Virginia know much about our traditional regional foods, for instance, apple butter or sourwood honey. “Is there really more than one kind of honey?” is not an unusual view to hold. Our understanding of place histories appears in most cases shallow indeed, and where at least some of the contours of this history (geologic, economic, cultural) are widely known, often lacking is an appreciation for the complexity and nuanced nature of that history. Historical knowledge is shockingly limited, simplistic and often just plain wrong.

The value of naming?

Why should we worry about the ability to name birds and trees and plants? What does knowing the name of a common local species indicate or suggest. Why does it matter at all?

I think there are several important reasons to hope for an urban populace and citizenry that can at least recognize common species. Partly I am concerned because naming implies claiming—not in the private property sense, but in the sense of seeing and perceiving something as being profoundly a part of the community of life of which we are a part. For something to exist in our human field of perception, it must be nameable.

The ability to attach a name to something seen in the landscape is critical for a number of reasons. Naming and recalling names implies a profound familiarity, and a recognition. To make the human parallel, my calling you by your name imparts a familiarity, an intimacy, and attaches a level of significance, importance, or attention that without a name is diminished.

A species common name often carries with it its own built-in trigger to stimulate the next set of questions, such as “how does this species live?” Trap door spiders indeed construct tunnels with camouflaged and silk-hinged trap doors that they can swing open to capture prey in response to insect vibrations. The biology of this fascinating creature, while of course more complex, is conveyed by its common name.

The words we attach to things are important on many levels. They signal the ways we interface and interact with the things—animate and inanimate—around us. Just as our ability to call a person by his or her name personalizes that individual, indicates a level of care and familiarity, our ability to name things in our larger place community must have the same psychological effect. The naming patterns of native peoples contrasts significantly with the Western European settlers, with a high density of names and naming that captures and conveys a special depth of knowledge and nuance.

When I visit a favorite nearby forest, and hear the lovely trill of a Northern Flicker, there is an emotional connection from that recognition that should not be undervalued. I know when I hear that distinctive rattle, I look around, searching for that wonderful, magical living creature with which we share the audible and physical spaces of the city.

Learning as much as we can about the nature around us is also arguably an element of basic citizenship—a necessary step in learning about and respecting the co-inhabitants of a biodiverse city.

Recalling names may be important for other reasons. Being able to recall the name of a species of fish, a type of rock, a valley or landscape or a human-designed structure, helps us to organize and remember information about these things: details and stories, and recollections, that further deepens our connection and ultimately our caring about them. Names then are sort of like place-holders; they provide us the opportunity to share and call forth additional texture and meaning.

Naming adds immensely to our enjoyment of the natural areas we visit in cities, and in the process of naming and recognizing, there is the development of a kind of nature competency that is at once rewarding and enjoyable, and imparts an important element of meaning to life.

Names as passwords to our hearts?

I’m certainly not the only one to wonder what limited knowledge and limited ability to identify things might bode for the future of community and environment. Paul Gruchow, a notable Midwest writer and essayist, has been one of the most eloquent of observers. He tells the humorous story, in his book Grass Roots, of the local town weed inspector who arrives at his home, in response to a neighbor’s complaint about an unkempt yard, only to be unable to identify any of the offending plants and shrubs in the yard (all of which Gruchow knew, and knew well).

More disturbing to Gruchow was the nature walk to a nearby lake he took a group of high school seniors, with similar inability to name or recognize the most common of Midwestern plants. Gruchow eloquently connects this to love, that essential thing that binds and connects us to one another and to the places and natural environments that make up our home.

“Can you,” Gruchow asked those high school seniors, “imagine a satisfactory love relationship with someone whose name you do not know? I can’t. It is perhaps the quintessentially human characteristic that we cannot know or love what we have not named. Names are passwords to our hearts, and it is there, in the end, that we will find the room for a whole world.”

Passwords indeed. They have become mysterious, unknowable passwords, that unlock intimate relationships that we have lost and are losing.

Now there are certainly many obstacles here and I am aware of the practical limitations of recognizing and naming more species. There are more than 10,000 species of moths native to North America, for instance, many quite small and hard to distinguish from one another, unless you are an amateur or professional lepidopterist. Much of our biodiversity in cities is difficult to see, of course, because it is very small, or is nocturnal. There are typically on the order of 40 or 50 species of ants in a typical American city, with a few common species that residents are most likely to come in contact with, but closely watching ants, and with an ability to analyze their anatomy sufficient to identify them can be challenging.

And we have been a culture that celebrates mobility and moving-on: the species and biodiversity of Los Angeles will be different than in Louisville, making it difficult to build up a deeper competency and personal knowledge base if one moves around a lot.

There are many other ways in which our contemporary approaches to names and naming raise questions about connections with nature in cities. We name many things in the human world, from sports arenas to automobiles, and often there are missed opportunities to name in ways that foster connections and impart knowledge about our natural environments. I have often thought that more could be done to tie our naming practices and protocols to the actual environments and landscapes in which we live.

Go Blatterworts!

Several years ago, in an effort to understand how schools tend to select the names of their mascots, I went in search a few statewide lists of high school mascots, to see the range of mascot choices, and if there were some more frequently chosen than others. A full list of high school mascot names for Illinois, for instance, was quite telling. There are some 27 high schools in Illinois (at least at that time) with “eagles” as their mascot, 23 that are the “tigers.” Most use one from a small pool of common mascot names—trojans, titans, hornets, lions, cougars, to name a few—that often have no particular connection to place, and no reference to native fauna or flora. Many of these choices represent species (if they are real at all) that are rather unlikely to be sighted locally. A sampling of Chicago area high schools includes cobras, golden tigers, mustangs and dolphins. One is (hopefully) not likely to encounter a cobra on a patch of green anywhere in the Chicago region, but perhaps has the desired effort of instilling fear in one’s basketball or football opponents.

Some of these Illinois mascot names are, to be sure, distinctive and some rather humorous—the Coalers from Coal city, the Appleknockers from Cobden, the Cornjerkers from Hoopeston. But there’s still a missed opportunity.

In recent presentations I have been challenging my audiences to imagine school mascots that might build on local biodiversity, especially plants, as a way of moving us towards a new nature and place sensibility. I usually offer some tongue-in-cheek examples: perhaps the Charlottesville hooded pitcher plants, or the Potomac painted trilliums, or the Albemarle Eastern Blue Curls, or perhaps the Lexington long bristled smartweeds. My all-time favorite imagined mascot is the Herndon Horned Blatterworts. “Go Blatterworts,” I’m not sure how this would sound at a track meet or incorporated into a cheerleading cheer, but it would certainly attract some attention, and I suspect residents would (begin) to at least know something about this plant. Would athletic jerseys be able to accommodate the “Johnson City Jack-in-the Pulpits.” This is not clear, so maybe this is a problem I need to work through.

While these suggestions for mascots usually get some laughs, there are legitimate and real issues here for us to consider. Partly out of expedience, and partly from a lack of imagination, many schools end up with bland (safe?) emblems and names that help to further extend and expand the patterns of sameness.

The names we choose for new buildings and public facilities are often equally telling. And what a different message this name sends than what is the increasingly common practice of naming dorms and buildings after large university donors. Everything in the modern university seems a commercial opportunity to raise money in these cash-strapped times. I find much in Michael Sandel’s critique of the application of market values to every aspect of our lives (see his terrific book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, 2012), including the naming of buildings and public spaces, notably sports arenas. While naming a dorm after a millionaire alumnus, or increasingly after a corporate sponsor, might serve to generate cash in hard times, naming after a local plant seems to help in not insignificant ways to counterbalance the otherwise ubiquitous messaging of what is valuable and important in the world.

Some interesting, though not perfect, examples can be cited of efforts to seize these naming opportunities on behalf of the natural world. When I issued my challenge about naming a school mascot after a plant at a recent talk in Arizona, I received an email on efforts there (Arizona State University) to rename the buildings in a dorm complex after local native plants. ASU students were given some options and asked to vote on possible plant names. Eventually the following seven were chosen as dorm names, all native flora: Chuparosa, Fluffgrass, Jojoba Bush, Wooly Daisy, Devil’s Claw, Fairy Duster and Golden eye. A positive and helpful step to take, especially in a city and a part of the world that in particular has lost any real connection to its natural setting, the effort has been belittled a bit by the students. Writing in the ASU newspaper, student Christopher Drexel has a humorous take, yet a serious concern about the chosen name (Drexel, 2006):

“But does anyone really want to live in Wooly Daisy Hall? It sounds funny on paper, but think of the poor saps—no pun intended—that will actually have to call the buildings home. What if you’re hosting your buddy from out of town and show him around old Chuparosa? What about if you’re bringing a member of the opposite sex back to your pad to hang out, only your pad is called Fluffgrass? What if your parents come in for family weekend and find you sleeping in Jojoba Bush. It would be embarrassing, plain and simple.”

This particular student, furthermore, rails at the University’s rule, the idea that such a practice of the Arizona-specific naming of buildings would be mandated. I must say that my immediate response to the student’s plea above is to say emphatically, “Yes, I would love to live in Wooly Daisy dorm”—it would sure beat many (most) of the alternatives.

Cynically, today much of the practice of naming buildings is about money: who has given it, and what it can buy. At a typical university today, the stadium, or dorm, or even a single classroom, often carries a donor’s name. That kind of recognition may or may not be deserved, but the message is clear—money and wealth are important, this is what we prize and honor and value, and will acknowledge. Such accolades and attention, moreover, are buyable and salable. The ecological naming practices that I have in mind send a different kind of message, I believe.

Sometimes, of course, efforts to apply names of natural and landscape features to built projects falls flat and seems hollow. Naming that new housing subdivision after the farm or forest that was destroyed to build the neighborhood is more an exercise in cynicism. But sometimes names like this can send helpful place cues that educate and orient. In my own city, there is a 1960’s shopping area Meadow Creek Shopping Center, a reference to the stream that runs through and around this site, and can still be found in a more open form just a few hundred feet away.

Understanding our local flora and fauna, being able to recognize and identify it is important indeed, recognizing the value of it to us, the importance and the esteem with which we hold it, are valuable alternative messages, made the more potent in this era of hyper-materialism. And if the dorm name elicits a “giggle,” so be it. It provides a point of conversation, a learning opportunity, a chance for some to point out the need to better understand the other creatures and life forms that co-occupy the landscape with us and upon whom we depend for so much.

I also wonder if a shift away from naming practices that celebrate the predatory and violent in nature, towards the deeper fascinating biology of place, would help in other ways. Perhaps one less high school supports team imagining victory and success in some other way than through gladiators and titans, in this way, the eastern grey tree frogs, or wooly daisies, might help to foster a gentler, less violent society (though to be sure, nature has its share of predation and fury). So much of the treatment of nature in the popular press is sensationalist and single-dimensional—emphasizing the fear of animals, whether bats that might carry rabies, or sharks or coyotes. The messaging is be careful, fearful, there is danger here, not wonder, not fascinating life-cycles or biology.

Not long ago I had the great privilege of interviewing Vandana Shiva, prominent Indian scientist, activist and environmentalist. She strongly believes that the language we choose sends important messages, often as at a deep psychological level. Our words send clear messages, and influence how we think as well. Shiva says: “Language shapes your imagination, not just communication.” She does not like the word “food chains,” for instance, because it reminds her of slavery, and so she prefers food webs, which better conveys the interconnected nature of our food relationships. She observes the brutal, violent names that companies like Monsanto give to their herbicides: “machete,” “squadron,” “avenge.” Our choice of names sends signals, but also shapes us and our relationships to nature in deep ways.

They are very important for many reasons, and part and parcel of our larger concern about (and remedies to) our disconnection from place and environment. Place and building names convey, or have the potential to convey messages, societal cues and signals about what is important.

An urban culture that values seeing and recognizing the nature around us?

What can or should be done to help kids and adults alike to advance or foster a culture and urban context within which we recognize (many) local species and are able to add them to our personal realm of community?

Starting at an early age, and conveying (parents, grandparents, neighborhoods) the message wherever we can, that recognition of and ideally knowing at least the common name of local species is valuable, important and rewarding—something worth doing, for a host of good reasons, including lifelong personal enjoyment and satisfaction.

Truth be known, it is less important to know the name than to recognize the species, and most important to care about and show interest in the nature around us—evidencing the spirit of wonder and curiosity (though again the former helps to cultivate the latter). In this way I agree with Rachel Carson’s eloquent call for parents to demonstrate this interest in nature even when they may lack the specific knowledge about the species and its biology. As she says so eloquently,

“It is not half so important to know as to feel. If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and impressions of the senses are the fertile soil in which the seeds must grow” (Carson, 1956, p.46).

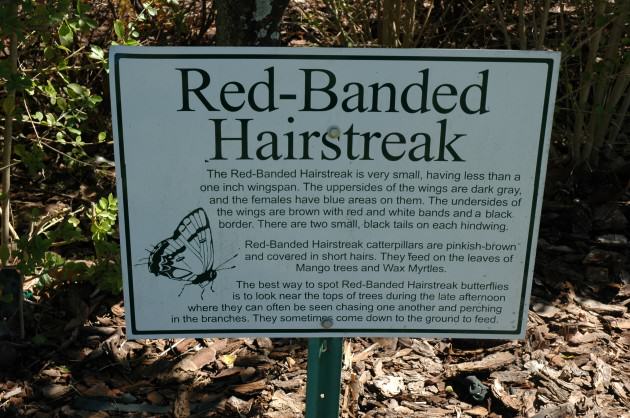

There are many things we might do to make this recognition easier. Clever and effective signage in parks and other public spaces would be helpful. We should also extend these educational and interpretative opportunities beyond the usual places—what might one see while waiting for the bus, or walking to the grocery store, or in the neighborhood cemetery?

Schools could play a greater role here. Several years ago I had the chance to visit an impressive elementary school in Western Australia, where birds and plants and other indigenous flora and fauna had been integrated into the curriculum of the school. At Noranda Primary School, several things stood out. First, it had behind it a rather large, restored bushland, an area of native gums and grass trees, and a place where students were likely to visit at some point during the day during their math or science classes. Many students there were even more deeply involved, participating in an after-school club called Bush Wardens. And most impressively students in all grades were exposed to a curriculum that involved learning about (and recognizing) the native plants and animals around them. I was surprised in seeing the guidebook used by the teachers that students would be expected to recognize common species of trees and birds, many of which would be typically seen on a stroll through the school’s backyard bushland park.

Being able to recognize and differentiate different species of gum trees is viewed, in this school anyway, as a necessary and important competency for students to develop. And the school had another important asset in in this task, the small area of natural bush behind the school where students and classes frequently visit, and where lessons in many subjects from mathematics to science to English find useful application in the bush.

Every city must provide abundant opportunities to participate in outdoor nature activities that help to build up interest and competencies and knowledge of the species around them. From birding clubs to neighborhood nature family adventure clubs to Bio-Blitzes that engage children and adults alike in the discovery and recording of nature, there are many news ways in which kids and adults alike can develop these recognition skills. Active assistance and coaching are helpful, as in programs like the Seattle Aquarium’s Beach Naturalist Program—some 200 citizen volunteers who, once having gone through training, spend time on the City’s shoreline parks, during low-tides, helping citizens to recognize and understand the amazing marine life that appears then. In the spring and summer of 2012, according to Janice Mathisen, who runs the program, these volunteer naturalists, wearing distinctive vests and red hats, provided information in more than 37,000 contacts with park visitors.

New citizen science initiatives further help in this way. For instance, the School of Ants, which encourages the identification and collection of ant species around the country, something greatly aided by a terrific online guide to identifying ants. The latter, a kind of flow chart for identifying key physical differences between common ant species, becomes an important tool for moving beyond simply “ants” to a richer, fuller understanding of at least some of the different species of ants, that co-occupy urban spaces.

Perhaps every home or apartment ought to come equipped with an insect aspirator—a funny device with a tube for sucking ants or other insects into a plastic or glass cylinder, making their identification much easier. And what else do we need? Certainly a good set of guidebooks near the window, perhaps a microscope at the ready.

Indeed this is one important measure, I believe, of a biophilic city—the extent and diversity of the opportunities and enticements to enjoy and learn about the nature around. From official fungi forays to classes in animal tracking, there are many ways that cities can foster and facilitate these intimate connections with the natural world.

New technologies and applications may of course help us here as well. I-birds and I-trees that make it easier and quicker to identify birds and trees. Sound-recognition apps might make it possible to wave a phone and immediately recognize the organism creating a sound, whether a bird or a snail. But one wonders, of course, about the overreliance on these new technologies, and if they will make it too “easy”, in a sense, something like the way GPS has made it easier to bypass learning about actual geography and physical orientation of a place.

There will be particular moments in life when people may be much more open to listening and watching, and learning the names of species around them. Moving to a new home, and a new neighborhood, might be one of these opportunities and I have long advocated for a kind of “ecological owner’s manual” that new occupants would be encouraged to read at least as closely as the manual about the new dishwasher or the garage door opener. These are opportunities when it might be possible to convince people that they should understand their new “home” in a broader sense—in terms of its biology and biodiversity, in terms of the watershed in which the house and yard sit, and, yes, in terms of an ability and to recognize and name the fellow creatures, those other neighbors, who are as much a part of your new home.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

References

Balmford, Andrew, et al., “Why Conservationists Should Heed Pokémon,” Science, 2002, p.2367, found at: http://www.bioteach.ubc.ca/TeachingResources/GeneralScience/PokemonWildlife.pdf

Beatley Timothy. Native To Nowhere, Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005.

Carson, Rachel, “Help Your Child to Wonder, “ Woman’s Home Companion, July, 1956, p.46.

Cassidy, Sarah, “Attenborough alarmed as children are left flummoxed by test on the natural world,” The Independent, August 1, 2008, found at: http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/attenborough-alarmed-as-children-are-left-flummoxed-by-test-on-the-natural-world-882624.html

Drexel, Christopher, “Around ASU: Plant Names Make Future Residents Poor Saps,” Web Devil, February 7, 2006.

Gruchow, Paul, Grass Roots: The Universe of Home, Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 1995, P.130.

Sandel, Michael, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012.

Great discussion about the importance of recognizing, naming, and caring about — and yes, loving — our wild neighbors. Here’s another way of considering the importance of recognizing — or knowing — a person, place, animal, plant, etc.: We only value and love that which we know; and what (or whom) we truly love and value we are most likely to protect with wholehearted ferocity and passion. Thanks, Tim.

My son knows the names of many plants and animals common to our NYC neighborhood including the Northern cardinal, red-tailed hawk, grubs, and London planetree. He’s learned from me and his teachers. And his grandparents have taught him about Jack in the pulpits, hermit crabs, and potato bugs among others.

I think young children are very interested in naming and collecting. They learn from the adults in their lives but for the adults who are less natural world savvy, we need sidewalk arboreta and flora/fauna cards similar to baseball cards, outdoor oriented “mommy and me” classes, and since people use them, apps, and more.

I really like your idea of an ecological owner’s manual! When I first started my blog I wrote a list of ways to learn about the local ecology of one’s neighborhood/city/region.