Vroom, buzz, roar, hum, zzzz, whine, chuffa-chuffa, whir, putt-putt, growl and shriek.

Acrid, penetrating, sweet, stomach turning, smokey, arresting.

These are the sounds and smells of machines, the machines that fueled by petroleum and are ubiquitous in the urban landscape, seemingly indispensible and unavoidable to the maintenance of urban ecosystem services. The smallest patches of lawn are mown by gasoline powered mowers, the grass is blown aside by gas powered blowers, hedges are trimmed with gas powered trimmers and gasoline fueled vehicles carry the laborers from site to site so they can deploy the machines to trim, cut, mow and tidy up yards, gardens and parks of all sizes and shapes.

There is little to no accounting for the impacts of these activities, not only for their contributions to criteria air pollutants and greenhouse gasses (GHGs), but also for the ways in which they impact the health of yard care workers, and residents. The noise associated with this work is never discussed: the invasive and pervasive sounds of motors whose decibel levels are poorly (if at all) regulated. The senses are assaulted by the banal and routine activities involved in “maintaining” our urban green space, ensuring it is orderly and well tended, controlled and clean.

EPA estimates that gas mowers represent 5% of U.S. air pollution, using 800 million gallons of gas per year. A new gas powered lawn mower operating for one hour produces as much volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides as 8 new cars each being driven for one hour at 55 mph.

EPA also estimates that over 17 million gallons of fuel, mostly gasoline, are spilled while refueling lawn equipment each year—more than all of the oil spilled by the Exxon Valdez in the Gulf of Alaska. One gas mower spews 88 lbs of CO2 and 34 lbs of other pollutants into the air every year. And these numbers do not account for the fuel necessary to create nitrogen fertilizer and the impacts of the use of that fertilizer on water quality and soils in cities. It has been estimated that more nitrogen fertilizer is used in cities than for agriculture in the U.S..

The perception of what constitutes the proper nature in cities certainly contributes to this sensory landscape. We are accustomed to an urban nature that is manicured and orderly, contained in both size and shape—no overhanging bushes or vines that could intrude on passageways—pruned up trees so trucks and cars can whiz along. Things are rectilinear and symmetrical.

Now, this is probably an over generalization, but nature in the city is contained and restrained so that it does not interfere with the free flow of commerce and movement, thus neither invasive or over bearing, nor wild or feral, except in reserved and controlled spaces. Lawns serve as out-of-doors wall-to-wall carpeting, ensuring cleanliness, covering soil—dirt—creating a sanitized green covering of what might have been originally the substrate for a mixed flora and the home of insects, microbes, birds, mammals and amphibians. Now instead there is turf, grown at turf farms, cut out and laid upon soil, then watered, fertilized, poisoned so no weeds will grow, nor any potentially destructive insects can live, and tended by poorly paid labor using machines that require petrochemical inputs. Critics of this system (Robbins 2007, among others) have pointed out the power of the lawn care industry (and the chemical industry) in creating societal norms about landscape. Change is occurring, but slowly as it involves not only an aesthetic leap, but also requires new knowledge, new plant availability, and new landscaping practices.

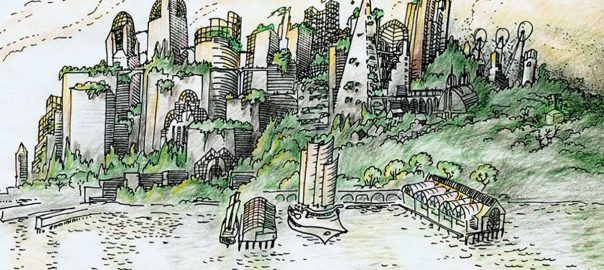

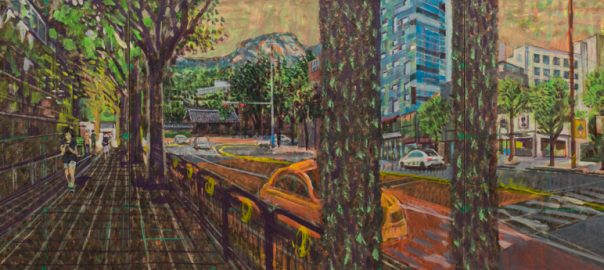

Our conceptual imagination is still challenged by what climate and ecosystem appropriate urban landscapes might look like. One of the issues is that urban landscaping is rather similar across cities, as Maria Ignatieva wrote in this space. Lawns and big trees in parks, lawns in front yards (and often in back too), easy to grow and maintain hedges, a few roses perhaps, and shade trees. But if we were to replace these with more climate appropriate landscapes in cities across the world, the variety and complexity of these landscapes would be extraordinary. We marvel at the differences in architecture in historic cities, architecture that has been often designed to be climate appropriate. White, tight cities along the Mediterranean, to reflect the sun’s intensity and to create shaded alleys for human circulation, and cisterns to capture scarce rainfall. Darker surfaced, less dense cities in the north, with slate roofs, for example, and drainage systems to evacuate rainfall and snow. With increased interest in vegetation and parks in cities, what would the landscapes look like if they too reflected their biogeography and climate?

For the region I know, California and Southern California, a Mediterranean climate region, urban landscapes would be shubbier, browner in the summer with exposed soil between the plants. Oaks might punctuate those landscapes, and the palate of flowering bushes, shrubs and ground covers would be not only diverse in size and types of flowers, but profoundly fragrant. We would have many sages, penstamons, bunch grasses, poppies, ceanothus and arctostaphylus among other wonderful plants. In the Northwest the landscape would be more mesic, with green full vegetation, azaleas and rhododendrons, and maybe turf grass. Trees would include firs, maples, madrones. Imagine the urban landscapes for Chicago, Dallas, Atlanta or Boston. What wonder we would experience going to those cities and feeling “in place” due to the urban gardens and parks reflecting their regions.

This transformation will be difficult for a number of reasons. One is the hesitancy individuals feel to change their landscaping when their neighbors have not. Another is lack of knowledge about different plants and their maintenance. Finally there is the issue of cost, which I partially address below. Landscapes are not inexpensive to change, and funding for this effort remains episodic and requires access to knowledge.

Redesigning the landscape of urban ecosystems fundamentally also requires addressing how they are maintained, and by whom. Today urban ecosystems are by and large anthropogenic—chosen by people and placed in cities regardless of native ecosystems. They are in that way novel ecosystems, almost entirely the artifact of human choice (putting aside the constraints of climate). They are chosen for their ease of management and maintenance, for their characteristics of greenness and homogeneity, consistency and predictability, across neighborhoods and parks, and for their responsiveness to mowing, blowing, pruning and trimming by easily available machines. They are seen as a matter of course today, and only starting to be questioned. Routinization of maintenance tasks, is important to reduce labor time, and one can even think of these landscapes as nearly Taylorized in their arrangements to be efficiently tended.

In Los Angeles, for example, the Mayor has pledged to open up to 50 new small parks, a good thing. One of the main criteria for the park landscapes was ease of maintenance—the ability of crews to come in and mow quickly and to move to the next park. A codified approach to park furniture was also developed to facilitate maintenance. Thus another important issue in considering urban nature is the question of labor costs and skills involved in landscape maintenance.

For private garden crews, the ability to make a living depends on the number of gardens they can mow and blow in a day. Machines make that task easier—it is faster to mow with a machine than a push mower, faster to blow leaves and debris than to rake and to sweep. Machines are also easier on the body—except that the emissions are toxic. The trade-off is between biomechanical injuries and cancer.

While there is growing recognition of the potential environmental improvements that could be provided by new landscapes that include trees, infiltration zones, climate appropriate plants and so forth, paying for the requisite transformation of the urban fabric and for its subsequent maintenance is a challenge. Not only are traditional city services like tree trimming being reduced, but the implementation of new approaches that use ecosystem services may need innovative new public/private partnerships to come to fruition.

Perhaps there are other ways to fund the transition away from the petrochemical, water and input intensive current system. Many urban residents today use gardening services to maintain their yards, the mowers, blowers and fertilizer administrators tending to the grass and flowerbeds. Depending on the amount of labor and the region, fees for such services vary, but residents from single family homes to multiple family apartments with outdoor vegetation commonly hire gardening services for routine garden work. This expenditure of private funds for a private service offers a tremendous opportunity to create neighborhood benefits through the establishment of neighborhood improvement districts, similar to business improvement districts. Such a program could capture the individual private expenditures to implement neighborhood nature’s services infrastructure. Street trees could be planted and maintained for individual and neighborhood benefit, infiltration zones could be created that would capture stormwater and runoff for groundwater recharge or irrigation purposes, benefiting the individual property and the neighborhood, and climate appropriate vegetation could be planted to better reflect local and regional rainfall constraints.

Not only would the individual property receive the environmental benefits, but if implemented at a neighborhood level, the sum of these benefits would be significantly greater than if implemented in a scattershot way at the individual level: consistent shade along the streets, less flooding or waste of water, reduction water-use and mitigation of potential water shortages, reduction of the use of fossil fuel inputs to mow and fertilize plantings, less pollution and impacts to public health. Neighborhood associations could be encouraged to develop these districts. The use of existing Home Owner Associations is an obvious path, but not all neighborhoods have HOA’s, particularly in neighborhoods of renters. Alternatively, there might be the possibility of integrating the maintenance of neighborhood-scale ecosystem services in existing landscape and lighting districts that already collect parcel-based fees for local benefit. Non fossil fuel dependent urban ecosystems maintained by neighborhood-pooled resources could be a new and powerful addition to transitioning urban vegetation away from the need to be so intensively maintained.

Using reoriented and pooled private gardening services thus has the potential to provide significant neighborhood level benefits that include:

- Maintenance of urban trees to reduce the urban heat island effect.

- The development and maintenance of distributed projects to reinfiltrate stormwater and dry weather runoff.

- The creation and maintenance of green streets including bioswales, rain gardens, infiltration planters, permeable pavement and other Low Impact Development techniques. As city budgets are reduced, neighborhoods themselves may be better suited to reconfigure existing infrastructure and to manage the ecosystem service-infrastructure. This approach will require innovative public/private partnerships since cities have traditionally been responsible for stormwater runoff and water quality, but there are examples of nonprofit organizations building bioswales in neighborhoods that could be the template for future efforts, in conjunction with city government and neighborhood stewardship maintenance districts.

- Reduction of water-intensive landscaping in planting strips and front yards and to better watering practices.

- The regular cleaning of stormwater drains to reduce trash Total Daily Management Load (TMDL), other TMDLs and potential flooding from trash-blocked stormdrains. Budget constraints of cities are making regular maintenance of stormdrain catchment basins less frequent, neighborhood level participation will improve water quality.

- Keeping green waste on site for mulching—enhancing rainwater capture.

- The reduction of the amount of fossil fuels used to maintain urban vegetation. With neighborhood level aggregated ecosystem services maintenance, stewards (retrained gardening services) can be hired to work in adjacent or single neighborhoods, reducing the need to travel across town from job-to-job. In addition, with more climate appropriate landscaping, fossil fuel inputs for mowing, fertilizers, blowing cut grass and so forth would be diminished.

A Neighborhood Urban Stewards program using the existing garden maintenance workforce for neighborhoods, funded by voluntary “Neighborhood Maintenance Districts,” modeled on Business Improvement Districts, could provide individual and community nature’s services benefits that would greatly enhance environmental quality in neighborhoods. Cities would have to develop agreements with the Neighborhood Stewards for the maintenance of green infrastructure in the public domain, much like how Business Improvement Districts enter into agreements with cities to provide additional security services, to keep streets in their districts clean, and to plant trees. Such agreements will vary jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

As cities advance green infrastructure strategies, programs and projects, a skilled workforce will be necessary. To date, the hiring of many cities has not kept up with the needs of the green infrastructure maintenance it has in place, such as street tree maintenance. An additional and parallel workforce could be responsible for the maintenance of the existing, and new infrastructure at a neighborhood level, chosen by neighborhood organizations, and trained by local community colleges. Community colleges could develop a Neighborhood Steward certificate program for these gardeners. The potential labor force would consist of the current numbers of gardeners who already provide gardening services in cities. Such a program would provide additional skills and knowledge to an existing workforce in water management and other green, skills and responsibilities.

Neighborhood level implementation is the appropriate scale for such services, as it reinforces neighborhood identity, cooperation and sense of community in the city. Such services would simply be additional to those rendered to private residences today. Homeowners Associations with dues, Business Improvement Districts with membership fees and dues are existing models for pooling property owners’ funds for mutual and public benefit. Homeowners Associations in some places already provide many of the traditional municipal services including trash collection and street maintenance. While different than an HOA because it would work collaboratively and cooperatively with a city, the neighborhood steward organization could be used to supplement city services in the transformation of public and private open spaces.

Pooling funds that are already being expended for yard work to also address neighborhood level outdoor infrastructure is potentially one efficient manner to approach the dual challenge: a new infrastructure and insufficient public funds.

Since there is a large, employed workforce already paid for privately, building on an already existing and compensated workforce to provide the green infrastructure maintenance services needed as cities advance their green infrastructure strategies, programs and projects.

This approach would not substantially increase the costs that residents already expend for “gardening” services. It could measurably reduce GHGs generated by this sector by:

- Concentrating the client base, reducing driving from location to location

- Reducing overall water consumption in cities for outdoor irrigation with watering being done by trained, neighborhood level stewards

- Reducing the amount of fossil fuels used in maintenance in the city –requirement that for certification, all blowers, mowers and other machinery be electric, or encouraging new landscaping that does not need this type of maintenance at all

- Increasing the health of the landscape worker, the neighborhood and beyond

Such a program would build on an already existing workforce, provide this workforce with additional skills, offer it an opportunity to organize itself into an association and obtain and offer receive health insurance as an association

It would engage neighborhood level groups and organizations in the management of their own green infrastructure, thereby elevating green infrastructure into their awareness and responsibilities.

Cities would have a workforce of neighborhood stewards to implement programs that currently it does not have the personnel to execute.

Such stewards can be responsible for cleaning stormdrains, but also prevent other pollution that gets carried to water bodies through intercepting bad practices, spills, and other occurrences that they might find.

If existing nonprofits involved in green infrastructure could be enlisted to develop and implement this program, it would offer them an opportunity to further their work in the city. This approach can also formalize an informal sector.

Stephanie Pincetl

Los Angeles

Leave a Reply