The Nature of Cities collective blog is now over a year old, during which time my friends, colleagues and co-authors have written many fascinating articles on various aspects of nature, and on people-nature interactions in urban environments. Today, in my blog, I’d like to step away from my previous two pieces—a discussion of tree diversity in Bangalore, and a tale of Bangalore’s lakes—to a more retrospective musing.

It all stems from Shakespeare (doesn’t everything?). My high school teacher, who had the unenviable task of teaching a bunch of bored teenagers The Merchant of Venice, highlighted how much his dramas taught us about human nature—and how little things had changed over time, really. Over time, although I began my urban research in Bangalore with a very ecology-centered view, it has become increasingly apparent just how important human behaviors are to this process. I don’t mean only issues such as people’s preferences for biodiversity—which, indeed, are very important. But equally important are how we perceive and deal with differences within us—differences in livelihood, in income, in lineage, but ultimately, differences in social status and in power. And, how our interface with these differences shapes the inclusion or exclusion of “others”, ultimately shaping the governance of the many ecological commons in our cities.

As in Bangalore,freshwater ecosystems including lakes, rivers, and wetlands are managed as common-pool resources in rural and urban areas in many parts of the world. Their inclusion into rapidly growing city boundaries is usually concomitant with a transfer of ownership and formal management rights to city municipalities. Yet—and especially in growing cities like Bangalore, Nairobi and Cape Town—urban commons are still accessed by local inhabitants practicing traditional livelihoods such as cattle rearing and fishing, although these now exist alongside recreational uses by city dwellers. Such contrasting and often conflicting users frequently engender heated debates about ownership and use rights, and bring up a whole host of complicated, thorny, yet very important equity issues.

Stories are always useful, to contextualize and explain abstract issues like context, culture and history to an audience unfamiliar with the place being discussed. So, I will provide two stories here. One is of an ecological commons, a lake being restored in today’s Bangalore. The other is a story of a British market being set up in Bangalore in 1811. Despite the considerable time difference of two centuries, the story these tell us of exclusion and inequity are unfortunately similar.

Let’s begin with the older tale first. On a recent visit to the Karnataka State Archives, I looked at one of their oldest documents: a file from 1811, filled with stylized, looped cursive handwriting that was extremely elegant to look at, but rather difficult to read. The story within was fascinating. The dusty file told the tale of the plan for creation of the Bangalore cantonment market, a plan originating from the officers of the Madras Presidency in Fort St. George, Chennai. A rather terse communication from the powers based in Chennai had apparently decided there was a real need for a market to serve the British troops based in the Bangalore Cantonment, which had been established just a few years before, in 1806. There was already a large and old market existing in a nearby part of the city, being used by the largely civilian population. Amongst the various factors cited as important reasons to establish a separate market for the troops was the need of a reliable place that could sell alcohol to them, clearly a need that separated the military from the civilians—along with problems of congestion in the civilian market.

The files note that the administrators in Madras realized there may be various challenges involved with summarily deciding to create and set up a large market in a populated area. Letters from Fort St. George thus request local British administrators to find out how many people lived in the area that was aimed to be transformed into the cantonment marketplace; how much compensation would be required to move them; and whether or not the king of Mysore would be much opposed to such a move. The letters exchanged thereafter, though rather brief, do not seem to record much possibility of opposition. Except for one rather disturbing piece of correspondence, what seems to be a sole surviving piece of opposition, that mentions that setting up of a Cantonment market would be challenging because there were forty to fifty thousand “souls” residing in that area. The correspondence in this file ends shortly thereafter, and we need to further trace what happened to this debate.

However, there was indeed an area set up as a marketplace for the Cantonment troops—whether this was in a location formerly occupied by the same forty to fifty thousand hapless souls described in the letter that I saw or not, we do not know. But we can speculate, probably with good reason, that there must have been some hapless souls inhabiting the areas where the British army expanded into, including those with livelihoods dependent on the commons such as grazers, fishers and agriculturists. What compensation would these souls, without well established private property rights, have received in return for handing over land for the provision of reliable alcohol sources for the British troops? Presumably little.

A lot can be read into this file, including tales of colonial power and hierarchy. Yet, tempting though it is to ascribe this tale of asymmetry solely to our former colonial past, my second story shows us that things have not changed that much over the past two hundred years. This, more recent tale is that of a lake in peri-urban Bangalore, within the city limits. The lake—let us call it lake X—was formerly encroached, polluted and drying, but is now well restored and maintained by a local lake trust, which takes great care to keep it in good condition. For instance, during a recent flooding event a few weeks ago at the beginning of the monsoon season, the members of the lake association acted quickly to divert the sewage contaminated water entering the lake into another direction, preventing it from contaminating the water within the lake.

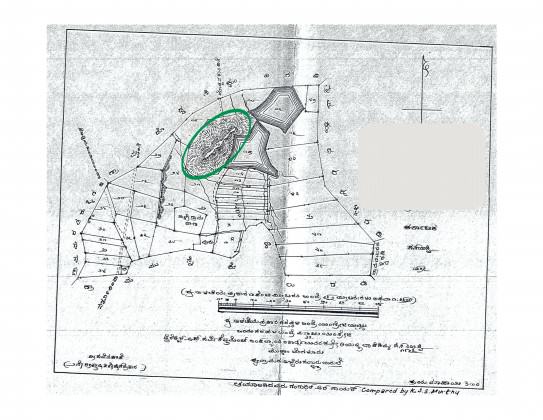

The story so far seems excellent, right? However, as with the story of the Bangalore cantonment, the restoration of the lake has not been without collateral damage. A map of the lake from 1970 depicts the area around the lake—including a grazing commons (outlined in green) to the northeast of the lake.

The photograph below shows you the area as it exists today—fenced off from the local community, with a small children’s play area overgrown with grass and weeds, surrounded by apartments. The lake itself is certainly well used by the local apartments and other residents around the area as a site of urban recreation. Missing however are traditional uses of the lake such as fodder collection and grazing, as has been seen in many of the other restored lakes in Bangalore. This portrayal is by no means meant to denigrate the quite significant efforts of those who have worked long and hard to restore and protect this lake. Quite the contrary. Examples such as this are difficult to find in cities like Bangalore, where most lakes lie degraded and polluted, and it is easy to see where the impulse comes from, to protect the lake from consumptive use.

Yet, there are inevitable questions of fairness and of equity.

There are no easy answers to these challenges. Open access commons such as those presumably existing in the areas designated for conversion to the Cantonment market in 1811, and those that definitely existed around Lake X in the 1970s, are of no use to anyone. Indeed, as Garret Hardin postulated (though somewhat misleadingly, equating “commons” with “open access” areas)—open access commons are almost inevitably going to be subject to dangers of overuse and degradation.

Yet, well protected, gated commons, though more sustainable, also pose the question of “protected by whom, and against whom?” Cities, whether in Bangalore, Nigeria, Moscow or San Francisco, are hardly paradises of equity. Quite the converse, cities are some of the most unequal places within which to live.

Unless we find some truly equitable ways to solve the challenge of equity, the issue of sustainability will remain ecologically biased, and socially skewed.

Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

Leave a Reply