“Human use, population, and technology have reached that certain stage where mother Earth no longer accepts our presence with silence.”

― Dalai Lama XIV

I am writing this blog as I am deeply disturbed by the colossal tragedy that happened in Kedarnath and Rambada region of Uttarakhand State on 15 June 2013 due to cloud burst as per few reports or disturbance in the glaciers in Kedarnath as per some others, whatever the reason be. This is one of the important pilgrimage centres in India and is considered as one of the Char Dhams (four must-visit pilgrimage centres).

There is still a debate over the number of people killed. Some estimates put the death toll between 5,000 to 10,000, and many people are still missing. In India, this is not the first incidence of flashfloods and cloudbursts. In 1908 one cloud burst was reported. After a span of 62 years, another cloud burst occurred in July 1970 in Uttarakhand. Since 1990s, 17 cloudbursts have happened to cause massive damage to lives and property, of which at least 11 cloudbursts occurred only in the hilly states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir. In fact, now this phenomenon seems to be highly frequent: 11 out of the 17 cloud bursts occurred only during 2010-2013. Experts say that the increase in frequency of such incidence is because of climate change.

While we can easily categorize this as a natural disaster, I attribute this as a human-made disaster. Ecological disasters are a result of disturbance in the natural rhythm due to adopting lifestyles and technology practices that change the basic constitution of nature. Uttarakhand, the place where the disaster happened in June, is located at the foothills of the Himalayan mountain region and is abundantly rich in forests, mountains and water and is an ideal place of hydropower generation.

While we can easily categorize this as a natural disaster, I attribute this as a human-made disaster. Ecological disasters are a result of disturbance in the natural rhythm due to adopting lifestyles and technology practices that change the basic constitution of nature. Uttarakhand, the place where the disaster happened in June, is located at the foothills of the Himalayan mountain region and is abundantly rich in forests, mountains and water and is an ideal place of hydropower generation.

We clearly know the real culprits in this case. It is not the nature but we human beings. I see this tragedy directly arising from destabilizing ecosystem services provided in Uttarakhand. There is massive deforestation in the region. Especially the hill regions due to their topography are extremely fragile, and deforestation along the mountain tracts would mean inviting the peril. Similarly, there has been a lot of sand mining along the river banks which change the natural course of the river, rampant and illegal construction to absorb the growing tourists, lack of proper urban and town planning along the hills, ridges and river beds, and building of hydroelectric dams to satiate the demand for electricity mostly from urban population. The last factor seems to be a key trigger in influencing the disaster and dams involve massive destruction of fragile mountain ecosystem through extracting resources from the riverbeds for construction, drilling tunnels, blasting rocks, laying transmission lines, running of giant turbines, along with altering the hydrology of the region.

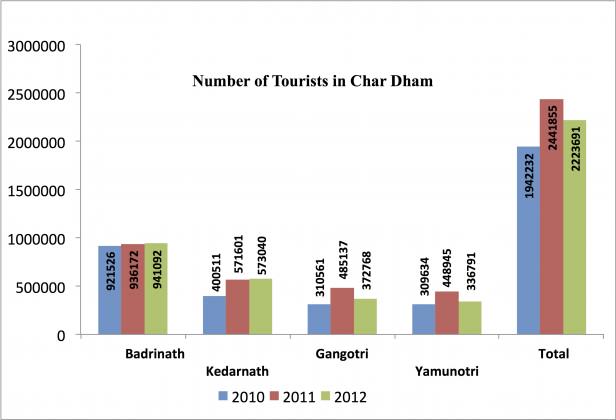

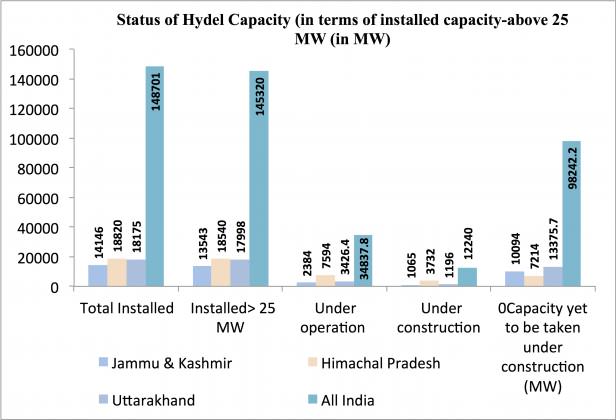

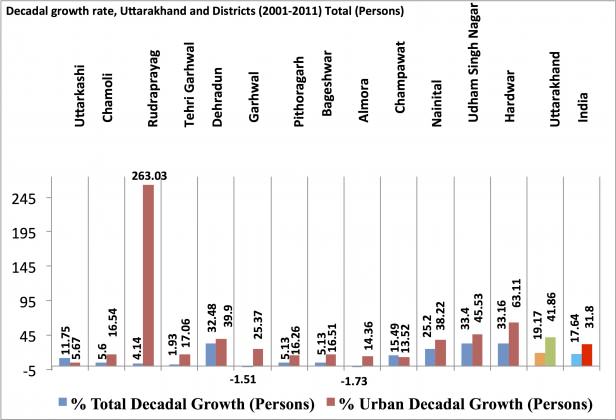

Statistics do not lie. We can see that the average annual growth rate in Gross Domestic Product of the state has been 18.6% between 2004 and 2012. The state could achieve such a growth rate due to the wide-range of benefits it offers to industries in the form of interest incentives, financial assistance, subsidies and concessions. The state has also undertaken several initiatives to attract tourists. Tourism has both direct and indirect impacts on the economy. The quality of the forest cover has declined and it varied among the districts. The decadal growth in urban population in the State has been 42% during 2001-2011 while the district Rudraprayag, where the disaster struck, has registered a growth rate of 263%. The number of hydroelectric projects in the hill states of Uttarakhand, Himachal and Jammu has increased and they generate 148,701 MW of energy and several projects worth 98,242 MW are in the pipeline. There are around 680 dams reportedly in various stages of planning or construction in Uttarakhand, in addition to the 70 existing ones.

Statistics do not lie. We can see that the average annual growth rate in Gross Domestic Product of the state has been 18.6% between 2004 and 2012. The state could achieve such a growth rate due to the wide-range of benefits it offers to industries in the form of interest incentives, financial assistance, subsidies and concessions. The state has also undertaken several initiatives to attract tourists. Tourism has both direct and indirect impacts on the economy. The quality of the forest cover has declined and it varied among the districts. The decadal growth in urban population in the State has been 42% during 2001-2011 while the district Rudraprayag, where the disaster struck, has registered a growth rate of 263%. The number of hydroelectric projects in the hill states of Uttarakhand, Himachal and Jammu has increased and they generate 148,701 MW of energy and several projects worth 98,242 MW are in the pipeline. There are around 680 dams reportedly in various stages of planning or construction in Uttarakhand, in addition to the 70 existing ones.

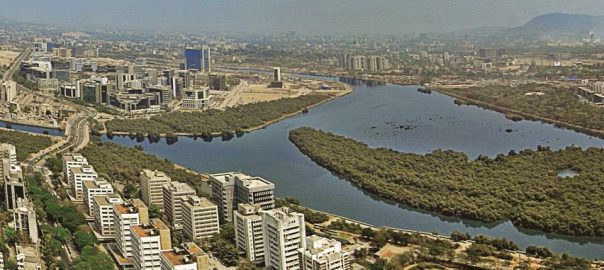

We know that most of this demand for hydroelectric power and better infrastructure comes from the urban dwellers, who do not even understand the relevance of ecosystem services to their everyday life. The problem lies in the mindset of most of the urbanized people and policy makers who think that a magic wand called technology is the key to all problems in India. Our technologies have proved to be regressive in terms of increasing the size of our ecological footprints. My last last blog addressed this issue on ecological footprints and addressed why we need to reduce our footprint.

We know that most of this demand for hydroelectric power and better infrastructure comes from the urban dwellers, who do not even understand the relevance of ecosystem services to their everyday life. The problem lies in the mindset of most of the urbanized people and policy makers who think that a magic wand called technology is the key to all problems in India. Our technologies have proved to be regressive in terms of increasing the size of our ecological footprints. My last last blog addressed this issue on ecological footprints and addressed why we need to reduce our footprint.

What does this mean?

There is a multiple organ failure in the form of institutional, governance and policy failures. In my last blog, I discussed that our policies are so short sighted that we cannot move beyond our narrow plans that concentrate on growth. This is like curing the disease even if the disease has multiple side effects. The disease here is curing the problem of unemployment and stagnation in production and consumption. However, there are multiple side effects in the form of ecological degradation, which will ultimately kill us one day. Is there a remedy now? We need to provide a quick fix to the technical snag in the system by addressing institutional, governance and policy failure by adopting integrated system approaches, rather than continuing a component approach.

It is not easy.

First of all we need to ease the pressure of human settlements and promote more balanced development models. We should respect the ecologically fragile zones and protect them from exploitation. This requires creating the ecologically sensitive zones in the states. The regions need (1) strict building and infrastructure codes, (2) undertake massive reforestation in the hilly regions, (3) avoid degradation along the slopes and (4) adopt a more cautious development model.

The growth should allow nature to breathe, regenerate and recuperate. We need to come out of the illusion called growth rate of GDP as the real sign of progress and focus more towards new indicators, which recognize the value of nature. If not, growth rate in Uttarakhand in a year from now would be much higher as a result of asset reconstruction, and we will suffer from an illusion that the economy is truly growing.

The Indian government convened an ‘expert group’ under the chairmanship of Sir Prof. Parth Dasgupta and under the directive of the Prime Minister. The report, a “framework for greening India’s national accounts”, was released on 6 April 2013. The report emphasized the necessity of recognizing all forms of capital as wealth—produced, natural, human and social—for measuring sustainability of the country’s growth. If the recommendations and road map prepared by the report are accepted, the country may seriously think differently about the way they make future assessments of their economic performance. And as a result we would think of different and improved planning strategies for eco-sensitive states.

Haripriya Gunimeda

Mumbai

Add a Comment

Join our conversation