This blog post takes the form of a seminar report. It is a reflection of the work of the City in Environment class of spring 2013 at The New School, New York. It is also a reflection on urban practice. In this class student explored and interrogated many terms that surround the urban environmental debate. In particular the five big terms: nature, landscape, sustainable, ecosystem and ecology were discussed and documented in a glossary. In short, we didn’t start with an issued based or rights based approach, but rather we learnt from past and emerging urban design and ecosystem science theories, frameworks and spatial strategies in order to discover what new hybrid urban practices might contribute to making positive differences for neighborhoods.

Who creates the art of urban practice?

The neighborhoods, all in or near New York City, were selected from a layered analysis using four datasets on a crop that partially framed the New Jersey Meadowlands, Manhattan Island, Jamaica Bay and Long Island Sound. The four layers, shown in Fig. 1, include the megalopolis highway infrastructure (grey), the New York City Bike Map (orange), a FEMA map of inundation by Hurricane Sandy (pink) and shopping malls or big box retail (not visible at this scale). These conditions intersect fifteen times (black boxes). Thirteen students had a site each, and shared their work on the class blog as well as presenting informally in the seminar each week. The base map was created as a prompt, with shared urban environmental conditions, in different combinations that are current to the region within an easy fieldwork range of the university.

The students come from a range of graduate and undergraduate programs across the university (MA MS International Affairs, MS Design and Urban Ecologies, MA Media Studies, BA Environmental Studies), and from around the world (Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, USA). The assignment is an academic exercise that leans on the full arc of a students learning, for example the International Field Program, and the Atlantis Program: Urbanisms of Inclusion. The class offers students tools through which to develop their own critical practice in a context of world politics. This means that student work was always discussed in relation to other urban environmental debates that surround development, democracy, participation, design, planning policy and imperialism.

The students’ final projects have been sorted into three clusters: chatting, extreme timing and after land use. Direct quotes and original drawings from the student blog posts are used here to share the project intent most clearly.

Chatting

These projects engage participation in urban change, through walking, chatting and online media. The term chatting is used here in the sense described by L. H. M. Ling from her forthcoming book The Dao of World Politics: Towards a Post-ˇWestphalian, Worldist International Relations. The book draws on Daoist yin/yang dialectics to move world politics from the current stasis of hegemony, hierarchy, and violence to a more balanced engagement with parity, fluidity, and ethics. She suggests new ways to articulate and act so that global politics is more inclusive and less coercive. One of the ways to act is chatting.

Emily translates chatting to mean a kind of informal, back-and-forth relationship with an environment through a walking tour. Alberto engages chatting as a relational circuit amongst walking and blogging and drawing and building and then more walking and so on. Samantha discovers that there is already online chatting going on, and her project plugs into this, inflecting it with new connections.

Fluid Experience

Emily Ball

“In the field of International Affairs, there is a strong concern with the categorization of economic and political processes. We have this notion that cities and even countries, basically any area that is formed by political boundaries, follow nice, non-overlapping linear stages that can be easily defined and organized. India is the world’s largest democracy. Pittsburgh is a post-industrial city. In using these simplistic descriptions we are able to simplify the complex processes within a geographical context and apply comparative analysis to otherwise distinct regions. However, in the study of cities, this urgency to define urban form and activity can lead to a sense that we have lost touch with important things happening in transition and have failed to fully realize the overlapping quality of stages …Have we lost sight of the integral relationship between human urban processes and the greater ecological systems for which we are a part? If so, in a chaotic climate era, how do we evolve to address our cities as ever changing and evolving urban ecologies? … With these questions in mind, I visited Red Hook, a neighborhood of 10,000 on the Southwestern tip of Brooklyn (New York), in early spring of this year and I was at once both more confused and utterly inspired.”

After a reflection on the contradictions she encounters, Emily then proposes a strategy of a changing walking tour as a generator for dialogue on urban change. She then offers her idea of the first walking tour of Red Hook including ideas for ways to engage and consider these urban spaces:

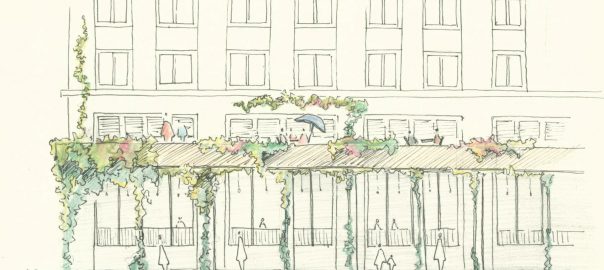

“I began to wonder how a waterfront community like Red Hook could redesign their vulnerable urban spaces in coordination with an alternative definition of stability. My proposal is a self-guided walking tour of the neighborhood beginning from the closest subway stop (The Smith St./9th St. F/G Station). The paths would change either seasonally or depending on topical events in the neighborhood so the physical path markers would be minimal and temporary and social media could be used to broadcast the route. The temporary nature of the paths would provide a broader metaphor for the shifting regimes inherent in our urban spaces. The path is a welcoming place for evolving ideas, concerns and desires in the community” Fig. 2

For example:

“The painting of waves presents a bold statement: “Some Walls Are Invisible.” The Mural is a project by Groundswell, a community public art program, and Miles4Justice, a Dutch human rights organization. They propose that the piece: ‘examines the ways that visible attributes of race and ethnicity can be invisible barriers to equality and justice. These barriers can be overcome with careful attention to our shared community and principles of human rights.’ This is such a strong statement of community engagement, I wonder if this work, or the area around it, could expand to include other visual representations of invisible barriers—in particular the community’s waterfront vulnerability. Perhaps an interactive flood marker could be installed which plays off of the waves in the mural.“

Walkscapes for Seacaucus: A Nomadic Observatory for an Inclusive Design

Alberto Salis

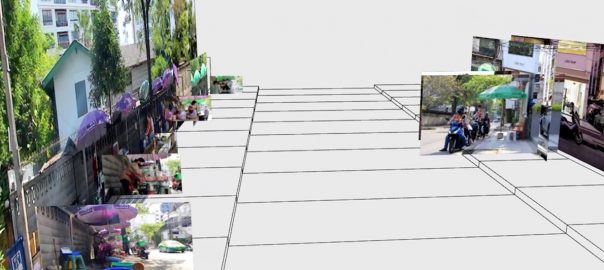

“The trigger of this work … is to deal with a certain rhetoric embedded in urban practice. In the latter years debates and topics around urbanism are more and more engaging participation and inclusiveness in projects and proposals by thinkers, planners and designers. It appears quite paradoxical this doesn’t happen within the creative process as well. It has to be said, of course, this assumption yet keeps in mind of any precedent attempt in this track. But still the impression is transdisciplinary communicativity in urban practice needs a deeper understanding. This project, in this framework, wants to be a starting point for a personal (no less shared) research around this topic.”

“A second trigger is related to environmental debate within urban design, and the complexity of the relations among what are generally called ‘anthropic’ and ‘natural’ environments. This duality here is meant to be argued. If it exists in expressive terms, it doesn’t as an actual concept. Even if it does, the relationships occurring between the two has to be dialectic, that is to say ‘anthropic’ and ‘natural’ delineation is not completely fit to describe the complexity of an environment. This statement, still somehow not yet mature and defined, is supposed to be provocative in a positively and propositive way, rather than being a defeatist critique.”

Albertos blog is divided into three sections that together function as a nomadic observatory: derive mindset (a journal where story telling invites the reader to establish an involvement and to take a critic statement, whether positive or negative), visual derive (paintings, graphic novels, video footage), operative derive (to metabolize the information into an operational agenda, as a milestone) and sketchbook (making design process habits inclusive). He explains:

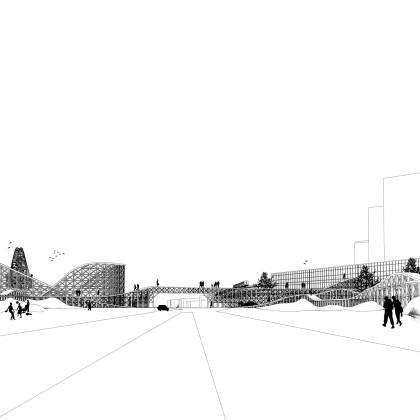

“Walking is put as a main carrier of meanings all through the project, as esthetic tool of urban investigation and urban practice … this project [is] the first spine of this practice, a proposal for walkable spaces leading to both psychological and environmental resiliency implementation in neglected and over-exploited urban spaces. In the design process it embodies itself in infrastructural intervention and reorganization in Secaucus, NJ.” Figs. 3-5

Scat: A sample of processing East Harlem urban design

Samantha Clements

“Public engagement as a method is used in development and urban design alike. In order to explore this further I have made a website that is a form of public engagement. It’s a sample of what I imagine would be a way of reaching out to the community through technology that already exists and combining information that is already presented in various forums online into one condensed website.

I used Tumblr as the host of the website because it is already a popular community orientated website (whether that be outside / established communities connecting online or communities forming around shared interests) and therefore there would not be an additional problem of driving traffic to the website, which is important because its an interactive extension of conversations already occurring in East Harlem.”

Samantha embedded a music video as a sound image in order to stimulate a better understanding of modern application of scat, which in itself is seemingly haphazard but really is a methodical chaos that is based off of set musical standards.

“The posts may seem a little disjointed but this is to simulate pieces of an urban design project coming together online. That is why there is a ‘site’ map updated to outline how all the pieces of the individual projects come together with any additional information needed. The hash tag system Tumblr utilizes allows for each post to be tagged with its project name any other relevant terms, users can then search for a particular term and see all posts tagged as such.”

Extreme timing

Space, typically thought of as a territory, is also something that we generate through thought in movement. These projects engage frames of time as types of spaces that are generative of new urban form and new urban forms of democracy. The goal is to correlate different time frames. Extreme timing translates dynamics of urban change that are currently generating stress and friction both environmentally and socially into urban form, making danger sensible. The projects are therefore a new type of reasonable speculation.

Thomas translates extreme timing to be a project of drawing long cycles of urban ecosystem change into each other to form a sense of enclosure with a sensibility of sand as an urban actor. Luca engages extreme timing as a long-term restoration project that starts with a sudden overnight move; closing a duplicated branch of highway I-95 and opening it as a pedestrian parkway. Veronica carefully captures the temporal gap between the creative flexibility of residents in a neighborhood and the rigidity of governance systems, finding it as a site for a new extreme timing organization.

Dynamic Dunelandscapes: A framework for the Shifting Sands of Coney Island

Thomas Willemse

Thomas presents Coney Island in his blog through its long cultural, very long geological and very short seasonal histories. He notes that it is a history of inversion (the super-natural opposite of Manhattan) countermoves (reclamation) and extremes (the most recent being Hurricane Sandy.) Inspired by his fieldwork, he explains (Fig. 6):

“…in October 2012 the shores of the island were once again swept clean, this time by Hurricane Sandy. The remaining fun fair was once more heavily hit, leaving the rollercoaster in the middle of a sea of water this time. Sea Gate was struck by an equal force of water that swept through many of the beach houses. But something else has also happened: the artificial barriers between the clearly delineated patches, that protected the ‘super-natural’ inside, have been breached. The escapist ambitions of one realm were blurred with those of another. The ‘naturally restored’ dunes of the Coney Island Creek Park shifted and buried the delineating fence of Sea Gate—and the lower levels of some houses—erasing this once so sharp border. On top of this breaches were slashed in the social barriers, bringing alienated neighbors back together in the recovery afterwards.”

“Perhaps instead of ignoring the disturbances throughout its history and reinforcing the inversion of the natural and re-erecting the barriers between the patches, something can be learned from the blurring that happened after Hurricane Sandy. A new relationship with the omnipresent sand can perhaps be found and some badly hit patches can learn the resilient ecologies of their neighbors. It might even close the circle of its history where the artificial ‘super-natural’ meets the natural again, just like the sand that continuously finds it way in between the patches of the island.”

For example:

“If we focus on one section in particular, crossing the beach, park(ing) area and residential towers, we encounter highly volatile seasonal dynamics on the shore, with a rapid succession of ecologies, then the amusement park area alternating between very high and very low intensities, until the very slow dynamics of the residential towers.”

What if:

“A wooden framework can be grafted on an existing pedestrian bridge that connects the boardwalk with the elevated subway train station. Perpendicular to this bridge wooden structures, filled with reeds, form first of all collectors of the sand that blows inland from the beach and secondly permanently stabilize the dunes. These dunes are then organized in such a way that they form a framework for a car parking lot, temporary event structures or attractions of the fair. Other hills of sand that might have formed in between can easily be cleared to open the areas in between the stabilized hills that are reinforced by the wooden framework. But the structure itself also becomes a facilitator for other uses to reinvigorate the patches. In winter and spring the framework is a boardwalk in a dunelandscape with lookout posts for bird watching. But transforms completely in summer in a rollercoaster of activities with a stage, a busy metro hub and a major skating area penetrating the residential towers.” Fig. 7

“In Coney Island the sand presents itself as ultimate carrier of the dynamics of its ecologies—shorebirds, water animals, sunbathers—and relates to different spans of time. The sand alternates with the short seasonal histories of the ebb and flow of the migrating tourists. But this revised process still brings new sand on shore to re-nourish now, not only the beach, but also the whole barrier island. And finally, as pointed out before, the ebb and flow of sand could become a major attraction in itself, intertwining in this way the natural and super-natural, bringing the circle of the Island’s history to a new dynamic close.”

Dynamics of Fragmentation

Luca Fillipi

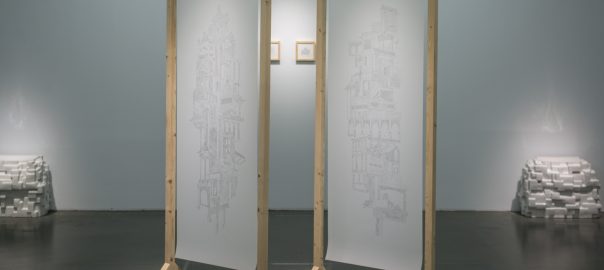

After an analysis of the disturbances created by socio-economic trends, Luca offers three integrated frameworks to guide change in the New Jersey Meadowlands:

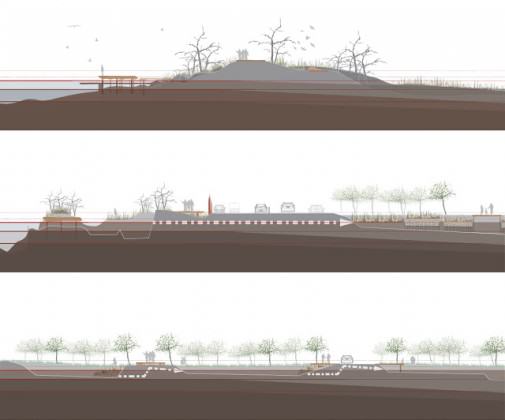

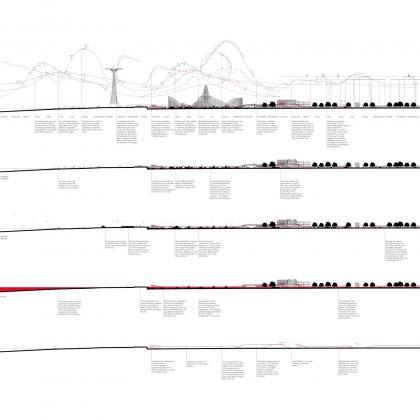

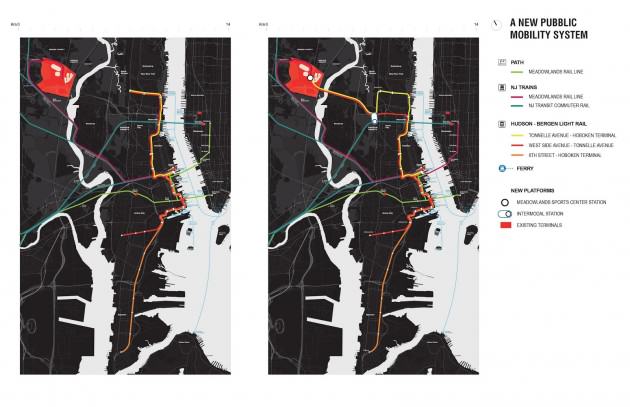

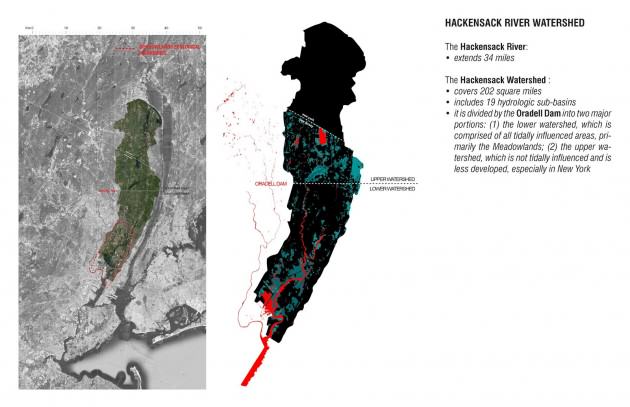

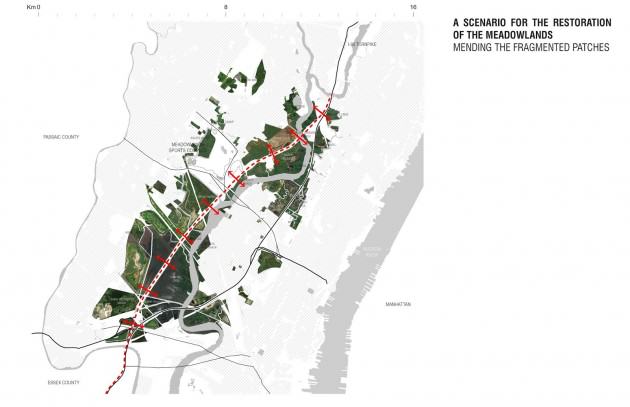

“The first one, called an “Inaccessible Landscape,” starts from a ground observation that shows fragmentation as a landscape dramatically cut by infrastructural barriers that deny a real point of entry into it. The second part, called a “Resisting Landscape,” tries to do a qualitative evaluation of the effects of the different dynamics and agents of fragmentation by using an ecological framework that is usually not considered in this kind of evaluation: the non-equilibrium paradigm. In this specific case, it will mean evaluating fragmentation inside an ecological model that accept it to the extent that it contributes in generating a more dynamic, and eventually resilient, ecosystem. The third one, called a “Disturbance Landscape,” develops the argument of the previous chapter by engaging the fragmentation as a disturbance in a landscape of disturbances.” Figs. 8-10

“I started this project close to the ground and I moved out from it for finding a way, a project, for going back there, in the middle of the swamp.”

I want to close this essay, started by quoting Bryan Zanisnik, referring again to his work. He writes at the end of his Beyond Passaic:

“…I took some steps to the east and looked past the facade, toward a paved parking lot with evenly spaced white lines and decorative lampposts. All this, along with American Dream Meadowlands, may soon be swallowed up by the marsh, I thought. But if not, the marsh may soon disappear or, even worse, be placed on maps”.

This quote, although absolutely beautiful, refers probably again to an idea of ecology that needs to be overcome. The interaction between human and nature in a way that do not exclude each other is possible and the project that we propose here try to show it. Time has maybe come to place the Meadowlands on a map.

The Metaphors of the City of Resilience

Veronica Foley

Veronica starts her project that engages parks, balance, and order with a discussion metaphors:

“Steward Pickett explains that the use of a metaphor helps create a connection between urban planning and the science of ecology”

“The past notion that ecosystems were constant and maintained a stable equilibrium has been replaced by the non-equilibrium paradigm that emphasizes dynamism, patch dynamics and resilience. Resilience is key to the non-equilibrium paradigm; it takes into account the many stable states of ecosystems. In order to evolve alongside the metaphors that have designed Jersey City, the city must plan for changes in the future. One way that the city can do this is by integrating its open and green spaces into a land trust. A land trust is a flexible urban infrastructure that can handle new metaphors of cities of resilience.”

Veronica introduces three parks, each of which are analyzed through the various metaphors that they engage: Liberty State Park, Reservoir #3, Harsimus Stem Embankment. Her proposal is to connect them as an urban forest trail managed by a land trust, which she describes as a new dimension democratic project:

“The proposed urban forest trail and the sites that would be connected increase the flexibility of Jersey City. These projects would help integrate the public into plans for the city’s future. The many organizations that have formed to support the already existing projects at the embankment, Liberty State Park and Reservoir # 3, have begun to rework how the city government functions.”

“A new dimension of democracy has emerged; these groups have organized to take care of the environment and also to fight for the same resources from the city. This democratization of the decision making process regarding the ecology of the city has lead to a system of governance that is more sustainable and a more sustainable ecosystem.”

“The land trust gives power to the people to create the spaces they want. The changing climate has prompted community to react with plans for sustainable change while sometimes city governments have different obligations that don’t allow them to be as flexible as community actors.”

“The democratic project that could begin once the land trust is established would transform Jersey City from the congested rail city of its past to a city of resilience. The land trust and the urban forest trail would be a platform for democratic and sustainable change.” Fig. 11

After Landuse

Speculative turbulence always surrounds the process of land use reclassification e.g., wetland to commercial, industrial to park, farmland to residential, low density to high density etc. At the same time the fine grain, block, lot, rooftop, sidewalk scale of changes persist such as crisis, disaster, decline, renovation and redevelopment. These are sometimes prescient of a new turn in land use categories, again setting in place another type of speculative turbulence. Can urban practice help correlate the actors who generate land use turbulence with non-equilibrium ecosystems better? The projects in this section offer land cover as a public engagement tool toward this goal. (See my previous post: Patch Reflection.) This approach is also of use in cities where there is no strategic land use planning and a lot of contested speculative urban change.

Noora translates after land use as a tactic of proposing several interconnected micro-changes as tangible requests to be a participant in various disconnected macro-decisions. Wendy engages after land use as a vertical strategy that moderates and makes climate change sensible. Jonas captures the speculative turbulence that is occurring after Hurricane Sandy to create more options for residents to stay in place.

Creating a Patchy Discussion for Corona Park and Willets Point

Noora Marcus

“I analyze the park both as a land cover patch and as located in a larger area of multiple intersecting land cover patches. Through a focus on the patch dynamics of the area of Flushing Bay and three design interventions, the roles, divisions and potential interactions between the green infrastructure and grey infrastructure in the area, are brought into focus. The narrative offered here is for public debate, with the objective to enrich the discussion on heterogeneous urban ecosystem change and the ideal of sustainability.”

“The goal of this narrative is to enrich the area through a strategy that does not erase the existing layers, but works to integrate the layers in new creative ways. The design proposals presented here aim to transform different patches (different land cover mixes) into new types of infrastructure (physical, social and aesthetic). Beyond the designs themselves, the narrative presented here aims to encourage the people of Flushing Bay to view themselves as part of the urban fabric of the park and the city, and to hopefully assert themselves as actors that can influence the potential of this space.” Fig. 12

Urban Strata in Transition

Wendy Van Kessel

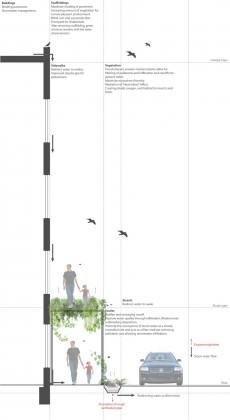

“Lower Manhattan is different. Walking through the streets you will notice that it doesn’t conform to the street grid of the rest of Manhattan. The streets have names instead of numbers, and avenues don’t exist.”

Wendy explored a strata section, a vertical analysis toward classifying vertical heterogeneity according to microclimate. Her analysis started from the view from the street, as well as the view from the water, focusing specifically on what she calls the ‘shrub layer.’ Her proposal for a Shoreline Portico aims to intensify the transition between the different urban microclimates. It marks the former shoreline of Manhattan, creates a semi-public terrace, and amplifies the explosion of sky that emerges when a pedestrian walks from from the ‘canyon’ to the ‘waterfront.’ Figs. 13-15

(See this link for animated river to river cross-section of Lower Manhattan)

(See this link for strata study of Lower Manhattan) Credit: Wendy Van Kessel

“Altogether, the proposed intervention is a way to reflect the different micro-climates within Lower Manhattan and with that has environmental benefits: reduction of the storm-water runoff, maximize ecosystem diversity, mediation of the “heat island” effect, create shade, oxygen, and habitat for insects and birds.”

“The benefits however are not only environmental; it will give the people a tool to think about their environment as an ecosystem and to be able to understand the differences in micro-climates, the elements that cause these differences and the negative effects by revealing the risk of flooding and the role that the city therein has played.”

“Giving more space to different species, creating more awareness, but also creating a more mix-used area… reflecting the functional transition of Lower Manhattan into an increasingly tourist visited place, with more residential and the persistence of business and commerce.”

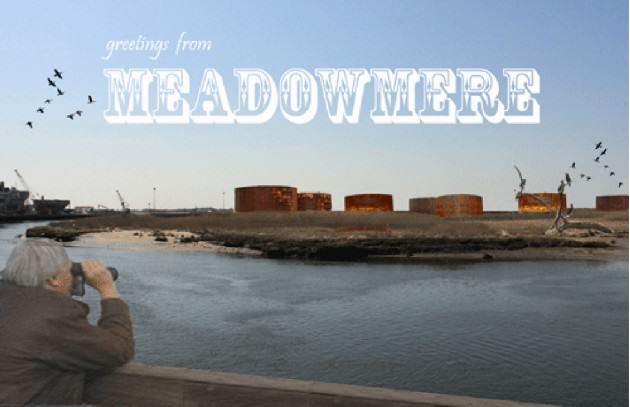

Adapting Meadowmere

Jonas De Maeyer

“Although belonging to the New York city area, you easily notice that Meadowmere is totally a different world. Together with Meadowmere Park, part of Long Island it was formed as a fishermen’s village, of which each part flanks a side of the slaloming Hook Creek. Together they are connected by a picturesque pedestrian bridge. The airport and the bay form physical borders and distance Meadowmere from the city and the city’s officials that have lost sight of it for a long time.” Figs. 16-17

“In general I see three strategies to deal with afflicted places as Meadowmere; Rebuilding, depopulating or adapting. Homeowners ravaged by the hurricane overwhelmingly choose to stay and rebuild rather than to take a state buyout. But is it really smart to just rebuild everything as it was? I try to understand the stubbornness of the community to stay and try to design adaptive solutions for rebuilding. We have to adapt the community to new floods, but certainly we also have to incorporate the earlier problems (such as the weekly street floods and the forgotten character of the area) and future problems (cost of rebuilding and increasing insurance costs) in the design proposal. I want a Meadowmere that is economically less dependent from the city and physically more resistant to rain and storms.”

Jonas did an analysis of three ecologies, which he describes as three different ecosystems that influence Meadomere and each other: airport, Jamaica bay and suburbia. In his blog he then proposes urban change using a micro-patchy approach that expands out from the front yard:

“Every moon tide the street floods and becomes impassable. There is more that can be done than blaming the City. By replacing impermeable front yards, mainly paved to park cars, we can plant permaculture gardens to absorb the overflowing water instead of directing it straight to the saturated sewage canals. This is the first step.”

“Meanwhile, we can start another strategy by bringing limited tourism. Different from other afflicted suburbia, Meadowmere has a strong locality thanks to its unique relation with the bay. Although a few people try to sell their properties, most people don’t to think of leaving their homes. They prefer to take the risk because they enjoy a lot living there. The S-shape of the Hook creek resembles to the Grand Canal in Venice.”

“To encourage more tourism and to save future re-pavement costs we can make Meadowmere car free. Meadowmere’s relation towards the water is therefore upgraded and the relation with the motorway is downgraded. The relationship with the megasupermarket can be changed as they can sell local products to their consumers. We can create a deal to share parkingspaces for the few cars still needed in Meadowmere and we can create a pontoon so that Meadowmere citizens can still go shopping with their boat to the shoppingmall … We can think of expanding the strategies towards the giant boxes and parking places and towards recovering the oil storage plant.” Fig. 18

Conclusion

Grahame Shane in his book Urban Design Since 1945 notes that urban design was created in response to emerging and overlapping city models and the disciplinary contexts designers find themselves in. Today, in the rush to access deregulated finance, the desire to explore new city models is often left aside, leaving those who are urban practitioners the job of trying to make a difference within the gigantic coupled city model; megalopolis – megacity, and the earliest and most persistent city model for New York, the metropolis. [Brian McGrath, Grahame Shane, “Metropolis, Megalopolis and Metacity,” in C. Greig Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds), The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, 641-657 (London: Sage, 2012)]

The assignment of creating a design project in a seminar, in a class of approximately half design and half social science students, was a request for a type of urgent reflection on our city models and the state of urban practice today. The students didn’t have the luxury of a semester long studio class to develop a deep design project, nor did the social scientists have an extended fieldwork and immersive literature review period. This rapid assimilation and expanded disciplinary experience is often the nature of professional practice today and therefore in itself and important experience.

The lessons of this class therefore position urban practice as an open topic with a physical and intellectual context, in particular learning from the Baltimore School of Ecology. [Science for the Sustainable City: Insights from the Baltimore School of Urban Ecology (Forthcoming) Eds. Steward T.A. Pickett, J. Morgan Grove, Elena G. Irwin, Emma J. Rosi-Marshall, Christopher M. Swan]

By offering the students two professional discourses; urban ecology and urban design, offering them a research neighborhood and asking them to put it all together in their own way in a collaborative classroom environment empowered them to see their ideas as important and generative toward new city models.

Who will create the next opportunities for these young urban practitioners to make more of a difference?

Victoria Marshall

Newark, New Jersey USA

With:

Stefano Aresti, Emily Ball, Samantha Clements, Luca Fillipi, Veronica Foley, Kelsey Gosselin, Alma Hidalgo, Wendy Van Kessel, Jonas De Maeyer, Noora Marcus, Martin Mayr, Alberto Salis, Thomas Willemse

About the Writer:

Victoria Marshall

Victoria Marshall's design practice is called Till Design. She is a registered landscape architect and is trained in both landscape architecture and urban design. Marshall is currently a President’s Graduate Fellow at the National University of Singapore where she is pursuing a PhD in the Department of Geography.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation