Ten years ago this month, in 2003, northeastern North America experienced the second most widespread blackout in history. That August evening, toward the end of my three-hour commute home on foot, a nearly full moon rose over the soft brownstone canyons of Park Slope, Brooklyn. Candlelit stoops hosted small, spontaneous parties serenaded by banjoes, guitars and accordions. Without the pollution of a million street and building lights the visibility of the night sky was exceptional.

But what arrested one most of all was the soundscape of insects. It was as if, for one night, the crickets and cicadas had been given reign over New York; the city streets a symphony of a million minor territories and matings. It was a wet, reverberant carpet that came over one in waves.

Had those insects had always been singing beneath our aural radar? Or had they availed themselves of that perhaps once-in-a-generation niche and taken the cue of the lack of air condensers, ventilation fans and amplified music to raise their voices.

I Plus Ultra

In 2004 a friend of mine invited me to the Metropolitan Opera’s season opening featuring Karita Mattila in the title role of Salome. Having progressed through Strauss’s key modulations and ambiguous tonalities, Mattila then performed the lurid Dance of the Seven Veils. At the end of this incestuous strip tease, she took to centre stage, to a background of audible gasps, completely naked. (It took sixty years for a production to actually follow this staging as the composer intended, and afterward many still used a skin suit.) Salome’s kiss of the beheaded John the Baptist—the reward for her dance—was equally sensational, but it was the orchestral chord in the final minute that I found particularly chilling. At the curtain call the audience cheered and booed the directors in equal measure.

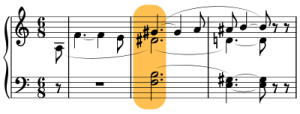

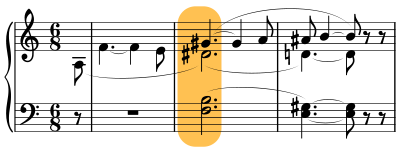

I found this curiously puritanical for a New York audience. But then Salome had always had a controversial history for its combination of the erotic, religious and murderous. Numerous opera houses refused to stage it in the early 20th century because of the nudity and its overall thematic material. But for me the unshakeable impression of Strauss’s work is not so much the subject matter or its explicit visuals, but rather its sound and the way Strauss forces us to open our ears. Throughout the orchestra plays symbolic leitmotivs signaling the presence of the title characters, much like birds signaling the approach of a predator (in the case of Salome). And there is the famous, dissonant, polytonal chord in the final minute. By crushing together A7 and C#-major chords, Strauss was said to have produced ‘the most sickening chord in all opera.’

A generation prior, Richard Wagner had begun experimenting with new tonalities. Like a breath of fresh air, the opening passage of his Tristan and Isolde is for many music historians the birth of atonality. The ‘Tristan chord’ that unexpectedly enters in the eighth second of the opera rests on a dissonance composed of a root, augmented fourth, augmented sixth and augmented ninth. In music before that point, composers essentially employed dissonance as a brief moment of tension that was quickly resolved; a superficial frisson of controlled excitement. Wagner makes a point of focusing on the sound that would before then have been heard as a distraction; perhaps even noise. The effect is sublime.

Nowadays the tonalities of Wagner nor Strauss are not terribly controversial. But new sounds—or any sounds outside of the most common spectrum of tones, or outside of what our expectations are—still provoke skepticism if not outright outrage. In 1952 John Cage premiered his 4’33” in Woodstock, New York to the delight and consternation of an audience who sat through three movements of an orchestra instructed to play nothing. In fact it is the audience that creates the ambient sound that fills these movements. Some of that audience literally walked out mid-performance. But for Cage, there was no such thing as silence. His intent was to frame the dynamism of the sounds inadvertently created by the orchestra players, audience and environment outside the concert hall.

Why so much outrage? I suppose it depends on our expectations of music. If we expected more—or perhaps less—our broadened minds might allow us to hear more. How much more would we hear? What kind of voices might we discern in all the noise? Would we no longer hear noise but instead just another form of music?

And if we did, would we realize that our music probably came from nature in the first place?

II Tonal inspirations for classical music

By the mid-20th century musical composition had already reached a high degree of abstraction in its preoccupation with serialism and dodecaphony, an abstract formalism in which all twelve tones carry equal weight with none occurring more frequently than the other. Like urbanism of the time, it suggested a complete, practically irreversible divorce from vernacular. But it also reached a new degree of complexity with polytonality and polyrhythm. Composers in the 1960s were experimenting with electronic sound and the imitation and sampling of ambient sound for their sonic textures and patterns. Both nature and the city played inspirational roles, either as borrowed voices or as entire organizing principles. Some specifically imitated or embodied the voicing of animals and the soundscapes they created. Others focused on man-made machines and their own industrial soundscapes.

Charles Ives was famous for incorporating ‘unearthly’ harmonies and ‘cacophonous’ soundscapes into his music. Often he employed thirteenth and fifteenth chords that essentially touch all tones in the scale. Or he created music out of the cacophony of multiple marching bands playing simultaneously, layering both onstage and offstage players. Ives was virtually ignored during his lifetime, but has since posthumously enjoyed a surge in academic and performance-based interest. Much the reverse was the Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera whose work achieved greater renown in the middle of the last century, but who has since been somewhat ignored in the academic literature. Ginastera was known to admire Artur Honegger’s Pacific 321, which articulates the journey of a train from its initial ferric rumblings to its steady clip across the landscape. He was also a keen admirer of Bartók, equally polytonal, who happened to coin the phrase ‘night music’ to characterize the slower, ambient passages in his works that suggested the sounds of nature at night.

Recorded example of polytonal chord can be found here.

Partial recording of Ives’s Fourth Symphony can be found here.

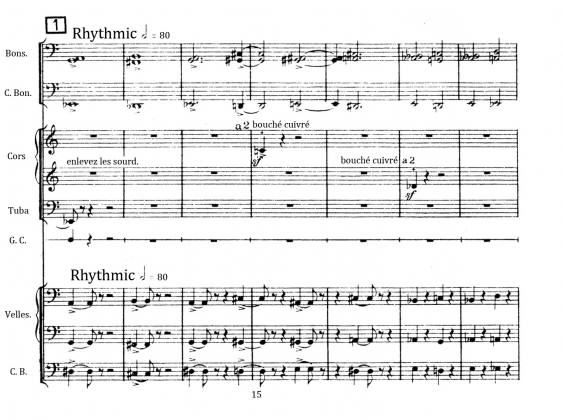

Standing out from most other composers of his day, Ginastera managed to balance a rigorous structure with an expressive meshwork of voices from natural world and pre-Columbian mythologies. Often negotiating between the two is the highly assertive, rhythmic stepwork of the Argentinian dance.

He achieves an abstracted sound that still assertively voices nature within its scope. This holds true from Panambí, his panoramic first work, to his posthumous Popol Vuh, which only had its premiere in 2008 (‘like radio waves reaching Earth after a two-decade trek from a distant star’, as one critic put it [Petert Dobrin, 29 March 2008: A creation score long aborning: commissioned in 1975, a Ginastera work got its premiere with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The Philadelphia Inquirer].

Rather than the melodious birdsong of other contemporary composers such as Bartok and Ravel, his was the ambient sounds of biophony (such as insects) and geophony (such as wind). The effect is relentless and frequently ominous, with a host of instruments furiously buzzing with the insistence that they too co-exist with human life. It is a curious and thoroughly compelling effect, a kind of sumptuous modernism that is rigorous with principle while still lush with nature.

A Popol Vuh recording is here.

III Listening to Natural Soundscapes

Musician and naturalist Bernie Krause urges us to listen more closely to natural soundscapes in their entirety, rather than simply for the purpose of identifying particular species. He began recording natural sounds in the late 1960s, when ‘sound fragmentation’—acoustic snapshots of solo animals—was en vogue and whole-habitat recordings virtually nonexistent. Manuel De Landa contrasts the two approaches as such: ‘analyzing a whole into parts and then attempting to model it by adding up the components will fail to capture any property that emerged from complex interactions.’ Such complex aural interactions can also be a potent place marker as they ‘generate an acoustic signature distinct to that location whenever times and conditions [are] comparable’. For example, baboons often wait to vocalize until immediately after a rain shower because of the ambient reverberation in the damp air. Coyotes and wolves choose the night because it gives resonance and distance to their calls.

Krause’s habitat recordings are accessible here.

Krause also illuminates the patterning and layering in natural soundscapes, referencing an old-growth Zimbabwean forest that ‘was so rich with counterpoint and fugal elements that is immediately brought to mind some of the same intricate compositional techniques used by Johann Sebastian Bach.’ That compositional whole would clearly have been lost in an accounting-style analysis of its parts. ‘In biomes rich with density and diversity of creature voices, organisms evolve to acoustically structure their signals in special relationships to one another—cooperative or competitive—much like an orchestral ensemble.’ Northern Pacific tree frogs sing in threesomes, each croaking one beat in a ¾ waltz with no voice overlapping the other no matter how fast the tempo. Humpback whales distinguish themselves with songs that ‘feature themes and structures commonly found in the most intricate forms of human music.’

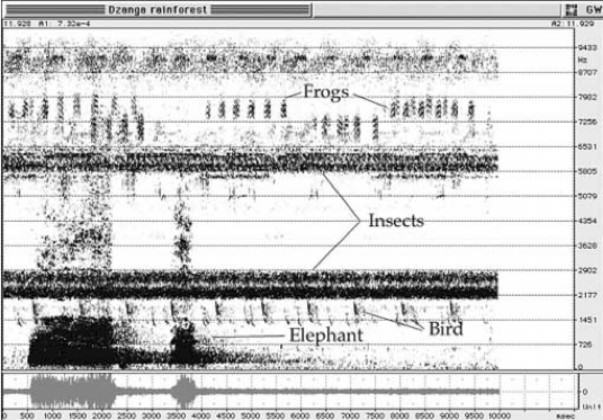

In Kenya’s Maasai Mara, Krause transformed his recordings into audio spectograms, which graphed the recordings in time and frequency, exactly the same diagram as an orchestral score that indicates time along its x-axis and pitch along its y-axis. Examining these, ‘niche discrimination plainly appeared on the page. Insects set the stage for every other sound, some by establishing uninterrupted drones that sounds continuously throughout each day and night, other by setting up rhythm patterns. Every bird species appeared to mark out its own acoustic turf. Mammals filled other niches, as did reptiles and amphibians.’

Lastly, Krause invites us to consider that natural soundscapes as the likely origin of human music. Over the course of life on earth, new voices and songs continually arose as various species evolved to fill vacant niches in the sound spectrum. (Doubtless this is still taking place.) ‘[T]he voices that make up these choruses are always adjusting slightly to accommodate for the most successful transmission and reception—a kind of perpetual self-editing mechanism.’ The human voice is no exception. ‘Early humans would have had an intimate relationship with their soundscapes; they would have learned to ‘read’ the biophony for essential information. Their music would have been an intricate, multilayered transformation of the sounds they were immersed in—the local creature life as a collective, as well as the sounds of the landscape.’

Listening to nature also means recognizing that its music inspired our own.

IV Listening to urban soundscapes

Lest we think there is a linear historical progression from geophony and biophony to the human voice, composed music and ultimately polytonality, polyrhythm and serialism, De Landa reminds us that history has never been linear. There is no strict advancement or retreat, and certainly no ideal end state. For him, the universe is composed of endogenous stable states with many possible bifurcations—Frost’s proverbial divergent path—that can change everything. Furthermore, virtually everything that exists lies somewhere on a continuum ranging from strictly controlled hierarchy at the one extreme to decentralized nodal meshwork at the other. Both human and natural habitats (e.g. city streets and forests) exhibit properties of extremes, and the sounds that emanate from them are equally compounded.

Listening to complete soundscapes in context, we understand that natural sound is not a ‘chaotic random expression’, but rather ‘patterns suggesting musical structures in the natural soundscape’ that become ‘too obvious to dismiss’. The same holds true for urban soundscapes. Bringing this full circle is the sound artist Giorgio Sancristoforo who turns the tables on classically composed music as the highest artform and mines the city streets for their inspiration of—and transformation into—music.

Let us consider a city, Milano, and try to listen to it, in its wholeness. Millions of vehicles and machines stirring chaotically, punctuating the rhythm of our affairs on Earth. We deem this ocean of unwelcome sounds mostly as noise. This soundscape eludes our control: we barely rectify it, yet we cant give it up, since its embodied in the truck carrying our food, in the tram taking us to work, in the construction site building our houses. It [is] the sound of contemporaneity. Sounds can be sculpted. We can use noise as raw material to start with. Noise is at the same time no sound and all the possible sounds. — from Giorgio Sancristoforo

Sancristoforo applies this exploration directly to the city street with ambient noise as his raw material. His project Milano Audioscan made a sound mapping of more than 1,500 recordings of Milanese streets. Each recording, made at exactly the same time of day, was then layered on top of the other to create a total acoustic portrait. To this he applied the ‘three stages of modern music technology: tape recording electronic synthesis and processing, and personal-computer-based digital audio’ to transform these sounds into electronic instruments. As the riveting composition progresses it becomes increasingly layered. At the beginning, however, one hears only the raw material: the combined sounds of the city from above are a nearly indistinguishable woosh of humanity and all its trappings. The single thing that registers, high above back and forth of humans and their machines and their machinations is the occasional counterpoint of a singing bird.

One wonders whether it sang in oblivion to that which was beneath if or, instead, if it recognized sufficient order in the chaos to add its own voice.

Audioscan Milano is accessible here.

V Listening in the silence

Humans are frequently so tuned in to particular signals for sound bites and easily interpretable messages that we often miss what falls in the cracks; the interstitial ‘noise’ with less obvious—but not necessarily less structure or rich—patterns. There is dissonance, but there is also silence. But even silence is worth listening to. Before long one realizes it contains its own voices. In what is frequently seen as a precursor to his composition of 4’33”, Cage was known to have visited a soundproof chamber. But even there he unmistakably heard the high and low frequencies of his nervous and circulatory systems.

Ultimately, whatever its habitat, each species finds its own wavelength on which to communicate. And the density and diversity of cities and biomes promote the acoustic evolution of human and nonhuman voices ‘in special relationships to one another—cooperative or competitive—much like an orchestral ensemble.’ Music evolves with its contextually evolving voices. These voices are as much opportunistic as they are spatial in the sense that they find and inhabit unoccupied niches in the soundscape. It may well be that fine-grained cities and mature natural habitats are indeed our ultimate listening experiences.

And, unlike formal orchestras, ones to which we can all add our voices once we find our niche.

Andrew Rudd

New York City

Leave a Reply