City planners have often many and innovative solutions for how to create a ’good urban milieu’. However, these ideas are mainly focused on accommodating visual aesthetics with necessary practical matters for transport, waste and energy. The dynamic sound perspectives in the urban environment, such as sonic diversity and acoustic ecology, are still very much neglected aspects in planning and architectural design. We are all in general largely unaware of the importance of sounds for how we perceive the quality of a place and a good living environment. Whenever urban sound is on the agenda the topic is primarily noise abatement and legislation to reduce noise.

But the challenge of how we may create an enjoyable acoustic milieu needs to be approached in much more creative ways.

Tim Beatley writes in his excellent essay “Celebrating the Natural Soundscapes of Cities” (January 2013) about the importance of engaging in the soundscape of the city, and that the city should be enriched with natural sounds. Tim points out that the fact that so many urbanites fail to recognize common nature sounds, suggests something about our disconnect from the aural realm and that we have lost the skill or desire to carefully listen to the world around us. Tim argues that the subject of sound needs to be put more squarely on the agenda of urban planning and design fields.

In this essay we will elaborate a bit further on the qualitative aspects of sounds and how innovative design may contribute to acoustic environments that people perceive as enjoyable and less stressful.

What do we know about urban soundscapes and how do we analyse them?

The study of soundscape is the subject of acoustic ecology and refers to both the natural acoustic environment — consisting of natural sounds, including animal and sounds from trees, the sounds of water, weather — and environmental sounds created by humans — through musical composition, sound design, and other human activities, including sounds of mechanical origin resulting from use of industrial technology.

Ecology is the study of the relationship between living organisms and their environment. Acoustic ecology is the study of sounds in relationship to life and society.

— Shafer (1977)

Studies of sound are broad and may include: acoustics, psychoacoustics, otology (study and treatment of the ear), noise reduction practices, analyses of patterns of acoustic perceptions and the structural analysis of language and music.

Much of the analyses and mapping of soundscapes have been done in North America but also e.g. in Sweden. In the US, the New York Society for Acoustic Ecology has been very active, developing projects that focus on the sounds of the urban environment and hosting lectures and concerts that encourage public dialogue concerning sound in cities. The New York Soundmap at Soundseeker.org allows the public to upload their own sounds that simultaneously get marked on an online map. In Sweden earlier this year, Gothenburg introduced a new research program called Sonorus. The Division of Applied Acoustics at Chalmers is coordinating this European project, training “urban sound planners” to reverse the negative trend of a deteriorating acoustic environment in urban areas. “The soundscape is determined as early as at the drawing board” — Wolfgang Kropp (Applied Acoustics, Chalmers University of Technology)

Increasingly, the study of urban sound is becoming an established research field in many parts of the world, with various methods, models and standardized ways of expressing the results. Soundscape studies represent an emerging and exciting research field that unifies the independent areas related to sound and environment. Although soundscape studies so far have been focused on noise pollution, many scientists and planners today argue for the need to make environmental acoustics a study program using innovative design to bring out the positive aspects of sound in the urban environment.

There is room for much innovation and experimentation on how design, architecture and the use of different materials and different types of plant species and other organisms may together create a new type of sound environment — not just noise reduction and not just natural sounds, but the creation of a hybrid sound environment that is the signature of what is urban.

What is noise?

We often refer to noise as “unwanted sounds”. The acoustic ecologist Schafer (1977) proposed three different types of noise: 1) unwanted sound, 2) unmusical sound (defined as non-periodic vibration), 3) any loud sound, and disturbance in signaling systems. The unwanted sound, loud sound and the disturbance of signal are independent factors, having the potential of leading to emotional responses often manifested in frustration. However, some view noise as “unrealized sound” that has the possibility and potential of being redesigned or put into a context that makes it more appreciated.

Noise affects human wellbeing in many ways. The threshold of pain is for most people in the interval 115-140 dB, naive listeners — that is, without training in the particular listening experience — reach a limit at approximately 125 dB, while experienced listeners can expand the limit to 135 -140 dB. Audiologists agree, however, that no unprotected ear should ever be stressed with a 135 dB sound. Constant exposure to moderate or intense noise levels will eventually lead to a temporary threshold shift, which is experienced as a loss of sensitivity when the stimulus is removed (Shafer 1977). For example, the sound output of the police siren has risen 40dB in many North American cities since the beginning of the last century as a result of more traffic, more street activity and an increased ambient sound level in general. The police siren needs to be heard through the highest levels of city sounds (recent research also show that the song of some bird species is affected in the same way).

This is a problem, and a rather complicated one. A siren in a noisy environment might be barely noticeable, while the same siren in a calm neighborhood might result in a temporal, or chronic, hearing loss if the attack is sudden. Another problem is the presence of infrasonic frequencies, i.e. sound waves 20 Hz or lower. These frequencies can, if intense enough, result in experiences of nausea and dizziness. Such frequencies are only felt as vibrations and are difficult to extract since they have a tendency to transmit through earth and building materials. We still know little about the long-term physiological and psychological effects of constant exposure to these frequencies.

Today, many cities have effective legislation to reduce the negative effects of noise and even though many (e.g. large Asian) cities may be perceived as very noisy, there are many good and effective experiences and practices that can be rather quickly implemented.

How do we analyze what is a positive and enjoyable sound environment?

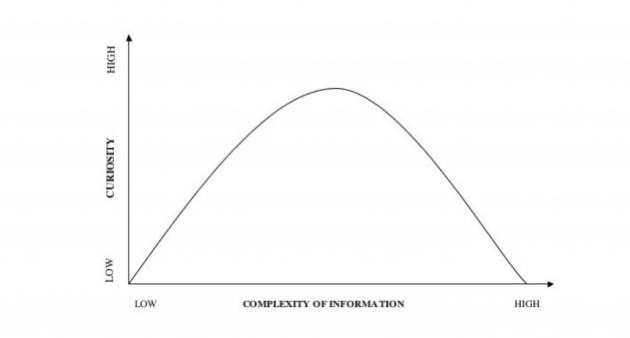

To move beyond just reducing noise levels and start innovative experiments of designing urban soundscapes that would, for example, reduces stress levels, we need some sort of conceptual and theoretical framework. Ipsen (2002) developed the Theory of Complexity focusing on acoustic complexity — or sonic diversity (see below).

In this model the relation between quality and the complexity of a situation is a non-linear, hump-backed curve. If the complexity of the information is rather low, humans may often find a situation less attractive. Also if the complexity is very high and ”unreadable” humans tend to react with annoyance. There is an intermediate level of complexity, between these two extremes, which generates a high positive motivation and this applies to any form of information, including acoustic perception. However, there is large individual variation. The same level of complexity of a situation may be attractive or unattractive, depending on the individual. The more familiar an individual is with a situation, the less complex the information input gets and the adaptability an individual possesses will influence the response to the acoustic information.

Each city may have a rather unique acoustic profile — the composition of specific natural sounds, signals and noise. Listen here are two examples from Stockholm and New York and an interpretation of the acoustic profiles of the two cities.

How do we proceed?

We can learn from theory that there is a complexity that is appealing to us, no matter the context. Urban sounds can be enjoyable for people in need of high complexity information. At the same time urban planners need to respect those who do not find the high complexity of sounds as attractive.

The solution for this would be the creation of zones and refuges, with varying acoustical complexity. Complete silence is impossible to achieve, but much city noise can be masked and dimmed. Using natural sound sources in urban planning, such as water and vegetation, has proved to be effective for this purpose and pleasing for the general public. Green walls can, if properly constructed, reduce up to 40dB of outdoor noise and vibration.

Parks were previously poorly designed, often a result of leftover pieces of real estate (Shafer 1977). Today, with a more detailed perspective on environmental sounds the value of sonic refuges, such as parks and open spaces, they should become a more pronounced part of urban soundscape planning.

Amanda Huron, geographer at City University of New York and working for the New York Society for Acoustic Ecology:

“One thing that I think works really well is the use of water to mask certain sounds, like traffic. There actually is a spot on 53rd street in Midtown here in New York that’s really easy to miss. It’s this little park that is just stuck between these two big buildings and you go in and it’s wonderful because it’s this total oasis. Part of the reason, I think, is because at the end of the park there is this wall and it’s just got all this water, it’s like a waterfall running down this wall, going down over this stone and there are trees. It’s just a wonderful spot. I really think a big reason that it’s so popular is because the water masks a lot of the city sounds. I’m really into plants, what they can do to increase the visual environment – but audio environment too maybe. I’m interested in this question about plants and how they absorb sounds, I wonder if succulent plants absorb more sound because their leaves are thicker.”

— from Pontén (2012)

There are many ways we could move forward. On the small neighborhood scale we could work on developing innovative design and materials — green spaces, green walls, water walls and other unrecognized ecosystem services. On the larger district or city scale we could work on the composition of urban soundscapes — e.g. “the dual soundscape”, including zoning areas with “silent parts” intermixed with more “noisy parts” and designing individual acoustic profiles for specific zones in a city.

Andrea Williams, co-founder of the New York Society of Acoustic Ecology, and involved in the New York Soundmap:

“I think that it would be interesting to have architects and city planners go on sound walks on a site where they intend to build. Such a walk based on listening to the environment and social atmosphere might inspire them to be creative with the design of the building and how it may interact with the soundscape around it.”

— from Pontén (2012)

Conclusion

Urban planning should involve more explicit zoning requirements for new constructions, which offers us the possibility to design soundscapes. However, there must also be an opportunity for people to choose their sonic environment. It would be unwise to impose a general sound aesthetic in ways we may have general visual aesthetics, since sounds are often perceived more subjectively than visual objects.

Acoustic ecology is not just an interesting new aspect of urban studies. We believe that through novel integration of landscape architecture, ecology, acoustics, psychology, innovative design, etc., soundscape design will be crucial for future city planning — building sustainable and pleasant cities.

Thomas Elmqvist and Emeli Pontén

Stockholm

Emeli Pontén can be contacted at [email protected]. Her work as a curator can be seen at Stocktown.

References

Hellström, B. 1998. The Voice of Place: A Case-study of the Soundscape of the City Quarters of Klara, Stockholm , Research Report: Royal Institute of Technology. Department of Architecture and Town Planning. Division of Complex Structures, Division of Design Methodology, Stockholm,

Ipsen, D. 2002. The Urban Nightingale – or some theoretical considerations about sound and noise. in H Järviluoma & G Wagstaff (eds), Soundscape Studies and Methods, The University of Turku, Vaasa, 2002, p. 185

Leave a Reply