Compared with other countries, Russia came relatively late to the world of market economy. It was a quite painful process as the Socialist planned economy changed to the demands of the market and working with private investors. Rapid urbanisation and new rules of planning require searching for new approaches to design and management of urban green areas in Russian cities.

St. Petersburg is the second biggest Russian city, with 5 million people. The city is famous as the cultural capital of Russia with its unique historical monuments and museums. The whole central part of the city is protected by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, and there are numerous historical parks and gardens. Green areas cover 7,209 hectares.

These facts leave a mark in policy discussions and require a special approach to the city’s development policy. The main task in central districts of St. Petersburg is, first of all, to protect existing green areas from densification and growing demand for parking. Compared to the central area, with its very dense built infrastructure, districts that were created later during the Soviet era have quite a high amount of green area. But after years of neglect and lack of management these green areas need extensive repair and improvements.

New residential areas constructed in recent areas are often lacking any greening. There is also another trend directly related to urbanization and globalization: a growing suburbia with individual houses that are “eating” surrounding green belt of native forests and coastal landscapes.

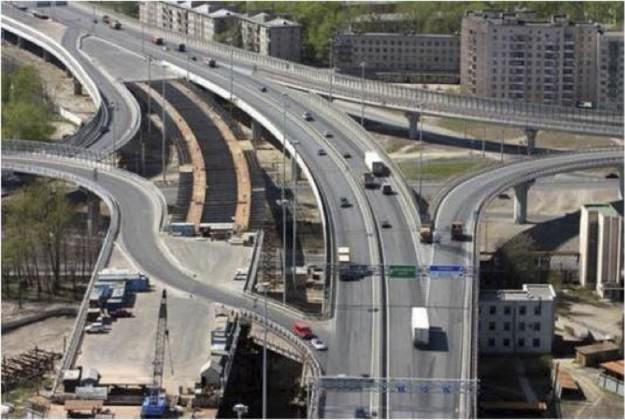

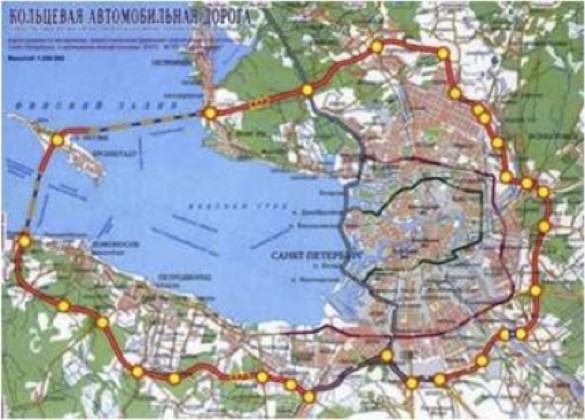

St. Petersburg has experienced tremendous growth of private cars, which has resulted in incredible traffic problems. The Old Baroque city structure is really struggling to accommodate such a number of vehicles. Even construction of the Ring Road has not help to solve traffic jams in the City.

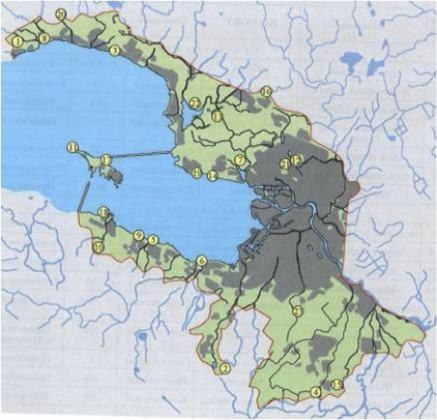

Another recent St. Petersburg phenomenon is directly connected to the new economic situation. Quite a few industrial factories in the central districts are closing and vacated areas are waiting for reuse. Looking at the plan of St. Petersburg it is quite easy to see the limitation of city’s growth. The most important is the Gulf of Finland and a big forest greenbelt.

At the moment the most disadvantage of St. Petersburg is isolation of the small central green areas from suburban residential greening (microdistricts — “microrayon” in Russian).

All these factors are contribute to the need for a new strategy of green infrastructure development. We believe that the following principles should be considered for the new sustainable green infrastructure in the city:

- Planning of green infrastructure should be an important and integrated part of the overall architectural and urban planning development strategy (master plan) of the city. It is a time for an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating principles of landscape ecology into urban design and planning. Principal St. Petersburg axes (along main streets) started in the central cities should have logical extension into suburban areas.

- New infrastructure should not be a random mosaic of different green spaces but interconnected infrastructure. One of the proposals is to create a system of ecological axes along main urban axes. They would start in the city centre with a system of green streets and pedestrian zones, then continue to newer residential areas and finally create relatively large green areas on the intersection of such axes, or lines.

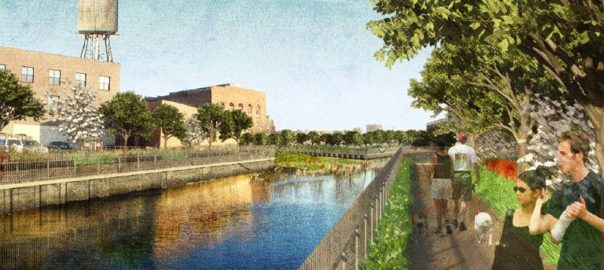

- Strengthen the links within the green infrastructure through the development of linear green areas along the main city roads and river embankments. This strategic line has a lot of potential in St. Petersburg, even in the historical central part of the city through organization of pedestrian zones with pockets of vegetation.

- One of the important principles of any new green infrastructure strategy is the relative autonomy of the individual parts of the green infrastructure elements. Different types of green areas should penetrate into the most important structural and functional urban planning in each of residential, industrial and recreational units.

- The organisation of new park areas in existing residential areas and the newly built up areas.

- Greening of embankments in St. Petersburg is restricted due to historical preservation. Most of Neva river embankments is covered by granite and is the part of the historical heritage. However there are still a lot of potential for river’s vegetation restorations of banks in smaller Neva’s tributaries and other minor rivers within city’s boundaries.

- There is a lot of potential for ecologically effective and rational organization of inter housing estates (courtyards) which are primary units of green infrastructure in St. Petersburg. For example, even the city centre — very restricted by heritage status — has potential for increasing green areas ratio by introduction of new technologies (e.g., vertical and container gardening, “green roofs” and “green walls”).

One of the goals today is to increase the level of green areas of St. Petersburg by 150 percent (compared to the present status) by moving some companies and businesses from the historic centre to the suburbs and re-purposing these newly vacant lands. There are quite a few already demolished areas which are planned to become new park areas. This strategic process should include reclamation of areas of former industrial sites and landfills of municipal and industrial waste and their landscape development.

The lack of land for urban development in St. Petersburg dictates another direction in green infrastructure planning: development of the coastal areas of the Neva River and the Gulf of Finland through the creation of new parks and gardens on the reclaimed lands. Park “300 years of St. Petersburg” is the most recent examples of such areas.

City of St. Petersburg has a lot of potential for designing green corridors along transport lines first of all railways and roads. Design peculiarities of public railroads spaces in St. Petersburg give the opportunities for introducing green areas. For example, spontaneously appeared parking facilities can be relocated to specially designed parking towers and the liberated space can be reuse for green recreational facilities. The most recent Ring Road (bypass) also great great potential by using motorway slopes for greening.

The pressure for private housing developments in the unique forest belt zones required a reexamination of existing legislation and tightening of protections for remnants of native vegetation and nature reserves in general. Thus, we insist on the idea of including water protection zones, sanitary protection zones of enterprises, and protected natural areas into the united green infrastructure system of St. Petersburg.

One of important tools for implementing a new green infrastructure strategy at intermediate scales in real neighboorhoods is using innovative approaches such as ecological design and low impact design principles of stormwater management.

In 2012 we used a typical St. Petersburg suburb, Novoye Devyatkino, as the first case study of implementing principals of Low Impact Development in Russia. Novoye Devyatkino has active residential construction and as a consequence its very limited green spaces face increasing pressure. The traditional approach to the design of the urban environment, promoted in Russia for the last 15 years, follows globalization trends and dramatically changes the face of the territory towards placeless landscapes. This approach usually does not take into account the character of the local plant communities and contributes to the creation of biologically unstable ecosystems.

Low Impact Design has been used in many European, USA, Australian and New Zealand cities. The key task of this design is to create a sustainable environment by using typical local plant communities. We also take into consideration the dynamic character of vegetation as well as respect the natural flow of water and its infiltration into the soil. The project has to deal with stormwater runoff without creating a network of traditional drainage systems, which in our case, is replaced by a chain of “rain gardens”.

One of the main challenges of our conceptual approach is abolishing the idea of a traditional lawn, which requires intensive management and maintenance (weekly mowing, very often herbiciding and pesticiding). Instead, the design proposes creating meadows, requiring a minimum of care and calling for the preservation of biodiversity. The project provides for the use of decorative groups of shrubs and trees, based on a mix of species from natural biomes, which will allow the creation of the “spirit” of the Karelian Isthmus.

The project also proposes a “public garden” where residents of neighboring houses could grow common garden plants and vegetables without using pesticides and fertilizers. We also introduce interactive gardens such as a “Garden of bugs”, “Garden of touch”, and “Garden of Sounds”.

Traditionally, the maintenance and construction of urban green areas in Russian cities is a task of specialized landscape companies (private or municipal). However the experience of European cities, for several years using the concept of ecological design, proves the success of direct involvement of local residents into the design, construction, and maintenance process. By introducing a similar approach we hope to reduce vandalism and increase social interest in maintaining and improving the status of residential areas.

Another positive aspect of this project is its cost effectiveness compared to traditional methods of improvement, as well as the possibility of preserving and increasing the biodiversity of the urban environment.

Maria Ignatieva, Irina Melnichuk & Andrei Bashkirov

Uppsala, St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg

Maria Ignatieva

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Irina Melnichuk

St. Petersburg Forest Technical University

Andrei Bashkirov

Landscape Architecture Firm “Sakura”, St. Petersburg, Russia

Add a Comment

Join our conversation