When we conjure up images of animals in temperate cities we think of such pesky creatures as pigeons, cockroaches, English sparrows, crows, rats and mice, while in other cities around the world urban dwellers encounter geckos, Indian mynas, monkeys, raccoon-dogs and baboons. In all of these cases, the organisms have adapted and they thrive due to the profusion of suitable habitats and resources provided by human settlements. With the current human population growth rate and the increase in the amount, size and intensity of urban development around the world, there are grave concerns amongst biologists, ecologists and conservationists that organisms that can adapt and thrive in human dominated landscapes will continue to survive and flourish while those organisms that can’t will decline and eventually go locally extinct.

Not too surprisingly, as human settlements expand there are a growing number of examples of iconic ‘wild’ creatures that have inhabited urban ecosystems, including peregrine falcons, bears, foxes, coyotes, deer, hedgehogs, koalas, kangaroos and microbats to name a few. Bill Sherwonit’s July 2013 post ‘Living with Bears: A Continuing Challenge in Alaska’s Urban Center’, discusses the increasing interactions between wildlife and urban dwellers in cities that are adjacent to wild lands such as Anchorage, Alaska. There are many examples in the news and in the scientific literature of unfortunate interactions between people and wild animals in peri-urban areas around the world. I totally support his message that we need to increase urban dwellers’ awareness of the actions we must take in order to live harmoniously in the same neighbourhoods and cities as these wild animals.

In our current efforts to create green, healthy and resilient cities and towns we (I include scientists, conservationists, architects, designers, planners, engineers, landscape architects, land managers, decision makers and teachers) have an obligation and the ability to create urban ecosystems that will support a diversity of organisms that can help preserve our natural heritage at local and regional scales. As a result of the research conducted by the staff and students of the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology (ARCUE) over the last decade, I believe we can move beyond living with a fairly common and limited pool of urban adapted species in our cities by explicitly creating urban ecosystems that provide habitat and resources for a diversity of organisms, including threatened species.

In the rest of this blog, I will describe one of our research projects that examined the expanding range of the nationally threatened Grey-headed Flying-fox (GHFF, Pteropus poliocephalus) into Australian cities and towns, which convinced us that we have the knowledge and skills to make cities around the world refugia for a diversity of organisms including threatened species.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Australia

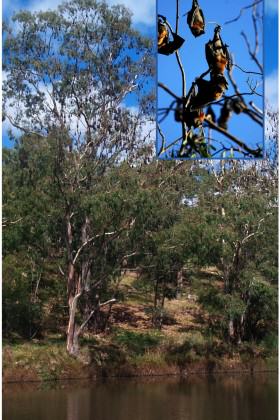

Over the past two decades there has been an increase in the level of interaction between humans and flying-foxes in Australia most likely due to a combination of cities and towns expanding into the range of flying-foxes, as well as flying-foxes establishing new camps within areas populated by humans. There are some 11 species of flying-foxes in Australia, found primarily in the northern and eastern coasts of the continent. Grey-headed Flying-foxes are megabats (Megachiroptera) that live in roosts (called camps in Australia) ranging from 10’s to 200,000 individuals and are commonly found along the eastern seaboard of Australia. There are ancient GHFF camps in two of Australia’s major urban centers, Brisbane and Sydney. GHFFs are one of the largest megabats, ranging in weight from 600 to 1000 g with a wing span of up to a meter (see the photo below).

Up close and personal, these bats are big. I have heard locals refer to them as chihuahuas with wings. They are also long-lived with an average reproductive age of between 6 and 10 years. They are very social animals that can forage an area of 50 km for food at night but congregate in pre-established camps in the morning. They primarily eat fruits and nectar from a variety of trees, but especially enjoy eucalyptus blossoms.

GHFFs are critical to Australian forest ecosystems because they play a major role in pollinating and dispersing trees in native hardwood forests and rainforests. They are listed as threatened under Australian Commonwealth law and are considered “vulnerable” because over the last several decades there has been a significant decline in numbers as a result of the loss of their feeding habitat and traditional camp sites due to deforestation. Unfortunately, GHFFs carry several serious disease threats to humans and other animals. The two most dangerous are the Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABL) which is a virus closely related to rabies and Hendra virus which is passed to horses and then from horses to humans. To date, there have been four human fatalities attributed to this virus in Australia.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes now call Melbourne home

In Melbourne, GHFFs have been recorded occasionally passing through since 1884. The first camp to be occupied year round was established in 1986 at the Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG). Over the following 17 years the camp grew exponentially from 10 – 15 individuals that remained yearround in 1986 to nearly 30,000 individuals in March 2003. The Royal Botanic Gardens was established in 1846 soon after the city of Melbourne was founded and is a much treasured cultural asset that receives between 1.5 and 2 million visitors a year. It was obvious to nearly everyone that 30,000 GHFFs camping in the Botanic Gardens during the day had negative impacts (noise, smell, plant damage, etc.) on the plant collections, RBG staff and visitors.

As the Director of the newly created Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology, which is a division of the Royal Botanic Gardens, I found this to be a very challenging research and management predicament. Something had to be done to reduce the impacts of the GHFFs on the RBG, but at the same time the health and welfare of the nationally threatened GHFF population needed to be maintained. Ultimately, a solution to this conundrum emerged from the combination of a solid scientific knowledge of the issues (i.e., ecology of the flying-foxes and the city) and a strong working partnership with the local GHFF management authority which in our case was the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment and other stakeholders.

To develop a solution to our conundrum we needed to address two primary questions: 1) Why did the flying-foxes migrate over 400 km from their nearest existing camp to establish a new permanent camp in Melbourne?, and 2) Was there scope for moving the camp to a suitable nearby habitat with less public access without negatively impacting on the health and welfare of the population?

Initially, the popular belief was that the GHFFs moved to Melbourne because of the destruction of the native habitat primarily as a result of the expansion of orchard and crop lands and more recent sprawling suburban developments. Upon closer examination it was clear that most of this land-use change occurred over 50 years ago and thus if it was a driving factor in the GHFFs move to Melbourne than it should have occurred much earlier. The primary reason other ‘wild creatures’ inhabit cities is because of the availability of much needed resources, especially food.

So, what had changed in Melbourne?

The urban forest of Melbourne, like many cities in the world, has experienced cycles of change in response to social, financial and ecological factors. Prior to European settlement, Melbourne supported only 3 species of plants that were important food resources for GHFFs. In the 1970s there was renewed interest in cities and towns throughout Australia to plant native species. Thus, in Melbourne there was a significant increase in the number of eucalypts and other trees such as Morton Bay figs from around Australia planted along streets and in parks and gardens. From our analysis of Melbourne’s street trees in early 2000, we found an additional 87 species that provided sustenance for GHFFs and other tree dwelling species such as lorikeets and possums. Not only were there more types of food resources available, because trees came from around the country with different life cycles they also provided blossoms and fruits throughout the year. This point is especially notable, because never before in the history of this species was there an abundant year round availability of food resources in a limited geographic location. Because humans cultivate and water these urban plants even during severe Australian droughts, cities provide an unprecedented food resource for many species of animals. We feel, in part, this is why GHFFs now call Melbourne home.

Once we understood that there was a huge year round food resource for GHFFs in Melbourne we needed to develop appropriate techniques to manage them in a way that would protect them from further harm while also limiting their impacts on urban dwellers. Using good science and a lot of help from volunteers, we were able to move the GHFF camp out of the Botanic Gardens. In 2003 over a period of several weeks, we herded the flying-foxes out of the RBG to a more secluded park along the banks of the Yarra River some 5 km away without any harm coming to the GHFFs or the public. We accomplished this by primarily playing loud sounds, which we had especially developed to excite GHFFs, from speakers attached to garden utility vehicles. This ‘new’ Melbourne GHFF camp has remained intact in this location for the last 10 years (photo below). The techniques we developed to manage urban GHFF populations has been adopted in other cities and towns in eastern Australia.

Over the last few years, GHFFs have established completely new camps in other cities in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. We believe that the replanting of urban forests in Australia with native species have provided a totally new resource for many Australian birds and mammals, but especially the threatened GHFFs.

As land-use change, drought and fires create an increasingly unpredictable food resource for these species, cities and towns now provide abundant and stable food resources for the future.

The take-home message from our Australian experience is that everyone should seriously consider what species are being planted in cities and towns around the world and it is possible to plant species that will, in the future, provide valuable resources for threatened and endangered species. Cities and towns definitely have the potential of becoming important refugia for threatened species’ in the future.

Mark McDonnell

Melbourne

Additional reading material:

Shukuroglou, P., and McCarthy, M.A. (2006). Modelling the occurrence of rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus haematodus) in Melbourne. Austral Ecology 31: 240–53

van der Ree, R., M. J. McDonnell, Temby, I.D., Nelson, J. and Whittingham, E. (2005). The establishment and dynamics of a recently established camp of flying-foxes (Pteropus poliocaphalus) outside their geographic range. Journal of Zoology 268: 177-85

Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries. About flying-foxes.

http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/plants-and-animals/flying-foxes-home-page/flying-foxes-about-flying-foxes

Williams, N. S. G., McDonnell, M. J., Phelan, G K., Keim, L., van der Ree, R. (2006). Range expansion due to urbanisation: increased food resources attract Grey-headed Flying-foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus) to Melbourne. Austral Ecology 31: 190-8

About the Writer:

Mark McDonnell

Mark has spent the past 25 years conducting ecological studies focused on understanding the structure and function of urban ecosystems, and the conservation of biodiversity in cities and towns.

2 Comments

Join our conversation