In 2002, I was working full-time as a social science researcher for the US Forest Service in New York City. My colleague Lindsay Campbell and I visited with leaders of the urban greening movement at that time — from community gardeners and park volunteers to environmental justice activists and tree planters, to directors of community service organizations and long-time government program staff. The message was the same: we need a way to capture the varied and wonderful ways that people are caring for the environment in New York City.

During this time, I was working on my doctoral degree at Columbia University. I met a sociology professor, Dana R. Fisher, who was also excited by the prospect of creating new knowledge about civic action and the environment in cities. Shortly thereafter, STEW-MAP was born — in many ways as a celebration and further understanding of local people who have been inspired by the environment, in its various and restorative forms, to bring about change in their lives and communities.

The Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP) is a research project led by US Forest Service researchers and cooperators that seek to answer the questions: Which environmental stewardship groups are working across urban landscapes, where, why, and how?

Stewardship can be an awkward term for some, so we settled on a clear definition. STEW-MAP defines a “stewardship group” as an organization or group that works to conserve, manage, monitor, advocate for, and/or educate the public about their local environments. This work includes efforts that involve water, forests, land, air, waste, toxics, and energy use. Many civic stewardship groups work within, alongside or independent of public agencies and private businesses in managing urban places. Over the years, STEW-MAP has become both a study of urban stewardship socio-spatial characteristics and a publicly available online tool to help support those networks. To see our multi-city portal, visit here.

Inspired by neighborhood change and revitalization

Years before, when I was working as an urban and community forester in southwest Baltimore, I met many people whose work inspired me to think of the city as a place of innovation and change, of generosity and understanding, of deep ecological knowledge. In the early 1990s, Baltimore residents were coping with ways to deal with entire blocks of abandoned homes, open-air drug activity, the everyday threat of gun violence and severe poverty. Many of the people I met chose to address troubles in their community through civic action: cleaning up vacant lots, planting flowers, creating afterschool programs for neighborhood kids. Many of these people were neither saints or sinners, but self-directed in teaching themselves the fundamental skills necessary to grow a garden next to an abandoned row house, to carve out a bike trail alongside old railroad tracks, to restore a neglected park to its former glory.

During the course of my work, I met an amazing photographer, Steffi Graham, who began to document people throughout the city who were caring for public and neglected areas. One afternoon, we set out to find a garden that was rumored to be producing the ‘best greens on the east side.’ We walked through a seemingly endless maze of vacant lots and back-alleys, and after a few hours we were about to give up. Luckily, an encampment of old timers sitting on the corner, shouted out to us, “what you two doing here?” We replied, “Just looking for the garden.” We were provided an escort back into the alleyway and before our eyes emerged row after row of the biggest collard greens and cabbages I have ever seen. Interestingly enough, these prize specimens were planted in the back yards of homes that were boarded and abandoned. Further back, across the alley and along the wall of a warehouse was a make-shift, fenced in yard that was overgrown with vines. We peered through the fence and came face-to-face with a large, metal shovel. Holding onto this shovel in a not-so-friendly way, was a man in coveralls. Clearly, he was the steward of this land. We quickly stated our intentions and after a period of time, our questions were answered.

Why are you gardening here? It’s where I live.

How do you grow such great stuff? I read up on things and watch other people, especially that guy who grows over on North Avenue. Him and I been watching each other for years. This year I got my peas in earlier than him and you can still see some over here……

Who is planting outside your fence, in the backyards? I am. That’s for anybody who’s hungry. This way, they won’t mess with my stuff.

How do you get water? I watch the weather and figure on planting plants that can take the drought, and, when things get real rough, the guys at warehouse lend me the hose.

Such exchanges, and many others like it, have served as evidence enough for me that urban residents are ecological thinkers who care for the land with a sense of stewardship, not unlike their rural counterparts, helping to care for forests, farms, rivers and grasslands. As I learned more about these innovative people and their projects, I realized that many received encouragement, information and occasionally modest funding from a growing number of bridging organizations, groups like neighborhood associations, clubs, and environmental civic groups that serve as an interface between government agencies and the local community.

STEW-MAP Today

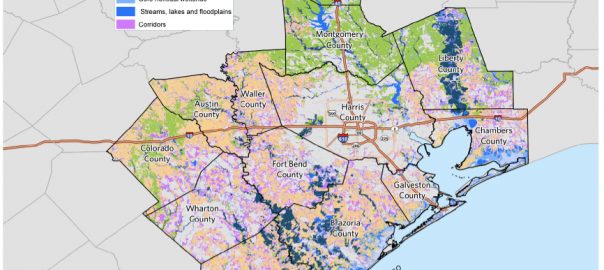

To date, STEW-MAP has collected information from thousands of local stewardship groups in New York City, Chicago, Seattle, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. These groups range from neighborhood block associations and kayak clubs, to tree planting groups and regional environmental coalitions, to nonprofit educational institutions and museums. Other cities, including Los Angeles and San Juan, Puerto Rico, are expressing keen interest in developing a STEW-MAP study and application.

What is shown on STEW-MAP?

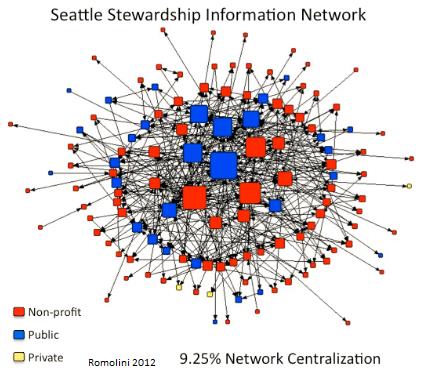

Stewardship maps tell us about the presence, capacity, geographic turf, and social networks of environmental stewardship groups in a given city. For the first time, these social infrastructure data are treated as part of green infrastructure asset mapping. For example, the interactive mapping website developed in New York City currently displays basic data for 405 groups citywide alongside other open space data layers. Other STEW-MAP cities continue to expand the NYC model and have created new maps and resources for their cities.

Why is STEW-MAP important?

STEW-MAP can highlight existing stewardship gaps and overlaps in order to strengthen organizational capacities, enhance citizen monitoring, promote broader civic engagement with on-the-ground environmental projects, and build effective partnerships among stakeholders involved in urban sustainability. Long-term community-based natural resource stewardship can help support and maintain our investment in green infrastructure and urban restoration projects. STEW-MAP creates a framework to connect potentially fragmented stewardship groups; to measure, monitor, and maximize the contribution of our civic resources.

Who should use STEW-MAP?

STEW-MAP is a tool for natural resource managers, funders, policymakers, stewardship groups, and the public. For example, managers in NYC have queried STEW-MAP to find stewards proximate to specific forest restoration projects run by MillionTreesNYC. Funders or community organizers can identify areas having the greatest or least presence of stewardship groups, taking into account organization size and focus area. Those seeking to disseminate policy information can target the most connected groups to quickly and effectively reach an entire network or a subset. Members of the public who want to know who is working in a particular neighborhood or who can provide technical resources for a project can search the database, which displays results as a list or on a map.

How is STEW-MAP implemented?

STEW-MAP is a research and application project that involves two stages. STEW-MAP 1.0 is the “lay of the land” data collection stage, during which the organizational population is inventoried, surveyed, and analyzed. This stage produces a database of stewardship organizations in the city, maps of where the organizations conduct stewardship activities, and social network analyses of the numbers and types of ties among groups. This work is accomplished in partnership between a local partner from the study area, a university partner, and a scientist from Forest Service.

STEW-MAP 2.0 is the “how do we use the data?” — the applied stage of the project. This stage includes the development of resources and tools that make the data easier to access and use. STEW-Map cities are exploring a range of visualizations for use in policy and practice. The Chicago team will be conducting focus groups in the coming months to enhance our understanding of user needs and applications. In Baltimore, federal and local participants in Baltimore’s Urban Waters Program are interested in using STEW-MAP data to facilitate their work: to increase collaboration, improve the flow of information and identify program gaps and overlaps. And in New York City, STEW-MAP data has been made available for a wide range of public uses, serving policy makers, program directors and the general public.

You can check out the New York City data here:

Where can you get more information?

Where can you get more information?

If you would like to learn more about STEW-MAP or ways you can develop a project for your area, contact:

Erika Svendsen, [email protected]

To learn more about stewardship work in a particular city, please contact:

New York City:

Lindsay Campbell, [email protected]

Chicago:

Lynne Westphal, [email protected]

Philadelphia:

Sarah Low: [email protected]

Baltimore:

Morgan Grove, [email protected]

Michele Romolini, [email protected]

Seattle:

Dale Blahna, [email protected]

Kathy Wolf, [email protected]

Los Angeles:

[email protected]

San Juan:

Tischa Munoz-Erickson, [email protected]

Erika S. Svendsen

New York City

Leave a Reply