This article presents an alternative perspective on urban nature that extends the debates on ecology in cities to ecology of cities. In Africa, and particularly Kampala, where we have undertaken research on various aspects of urban development, we are increasingly confronted by a realization that urban built up components are only conveniently “detached” from the urban nature on which these sit. In fact the combination of the built up and urban ecosystems is creating a unique urban form that is a fusion of interacting parts of the city as whole. Cities in other parts of the world that have benefited from long standing planning have the urban form which, to a degree, separates built up from nature areas as nature parks and recreation areas (Grimm et al. 2008). The design and planning has also reserved multi-purpose green parks, as seen in recent urban development, to respond to the environmental change challenges. In contrast, cities in Africa, as is the case of Kampala, can be described as ‘runaway’ cities by nature of the sprawl and fragmentation of natural ecosystem interwoven with built up land. This is a different worldview of urban nature with implications on how to maintain ecosystem functions.

In Kampala, there is evidence of continuous interactions and influences between built-environment and the natural components to form a unique urban fabric. This worldview helps us to understanding the urban system interactions at various scales. Our understanding of how the built environment components interact with nature on which it sits is key in addressing the challenges of urban management, and there is critical importance in sustaining some level of ecosystems functions of provisioning, regulating and supporting services (Shuaib Lwasa et al. 2009). The speed of urbanization in Africa is characterized by, among other things, the degradation and reduction in ecosystem services within urban areas. This dilemma is felt in Kampala where ecosystem services are dwindling due to land competitions for development.

The challenge is that the city is extending further into the rural hinterland. The reduction of ecosystem services along the urban-rural gradient is evident. Exportation of pollution and contaminants into the rural hinterland is also a key urban management challenge, while the importation of nutrients from rural areas and stocking the organic nutrients in the cities has benefits but it is equally of concern. Some of the ecological functions of urban and peri-urban agriculture provide immediate benefits to producers, most notably food production, while other benefits are realized as flood regulation.

The provisioning services provided by agricultural lands are among the most immediately important for the city population. Provisioning services include the production of grain, livestock, produce, fuel, and forage. Along with food production, agroforestry in urban and peri-urban areas of Kampala are supporting the growing demand for wood fuel, which continues to be an important source of energy for domestic use. Sustainable management of timber and non-timber resources from forested lands can be an incentive for sustaining ecosystem services.

Ecology of urbanscapes in Kampala

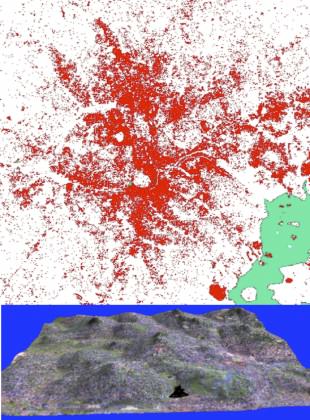

The growth and expansion of Kampala has altered the natural ecosystem to create a complex system of interactions. Surface conditions of the ‘urbanscapes’ play an important role in mediating regulating and provisioning ecosystem services. The increase in impervious surfaces and reductions of vegetation cover has an influence on the urban heat island (UHI) effect characterized by higher temperatures and less variation in nighttime and daytime temperatures.

While the continued practice in urban and peri-urban agriculture has formed a fusion of built up and nature with patches of nature surrounded by concrete and infrastructure. Urban and peri-urban agriculture regulates local microclimate to some degree but has also contributed to maintenance of vegetation cover in the city. Effects of changes in urban ecosystems include weather extremes and impacts of local temperatures, and increasing wind intensities, partly due to losses of vegetation. Increases in impervious surfaces associated with urbanization reduce soil infiltration and increase surface runoff during storms while lowering the water tables. Thus planning would have to address the reduction of storm runoff with more porous land surfaces to support recharge of water tables, increase groundwater flows and urban vegetation.

Though Kampala can be described as a ‘runaway’ city due to the nature of growth and expansion, its regional extent also offers opportunities to plan for development as a city-region to influence ‘urbanscape’ ecosystems.

Trans-boundary city and stock flows

Though we haven tended to look at cities as bounded spatial entities to inform and guide planning, development and investment, the nature of urban growth and expansion has gone beyond these boundaries. This nature of urban development relates to urban hierarchy and convergence of metropolises perspectives in which maintaining a hinterland around the cities as the source of supplies in fiber, timber, food, water and labor is important.

But cities such as Kampala are exemplifying a new phenomena of spatial expansion of the built up with continued reliance, to some degree, on resources from the immediate hinterland. The new feature is that cities have also consolidated distal relations with other resource producing areas, some of which have no direct physical connection with the consuming city. This has accelerated the flow of resources from the hinterlands but also from distal places, accentuated by global trade. In essence, cities are stocking materials and nutrients that originate or are produced elsewhere.

Some of the materials are exported back to the hinterlands and the distal places as pollutants, wastes and consumables. Studies have framed the flows as urban metabolism, which helps in understanding the inflows and outflows (Bohle 1994). The inflows that stay in the urban areas become part of the urban ecosystem in terms of landfills, wastewater treatment plants and concrete infrastructure. This influences the ‘urbanscapes’ of cities like Kampala.

Urban nature and biodiversity

Urban nature and biodiversity

Despite the fragmentation of urban nature in ‘urbanscapes’, there is continued recognition of the importance of cities in conservation of biodiversity (Loreau et al. 2001). The existence value of certain species is felt by people around the world, indicated by the extensive investment in global conservation efforts.

Biodiversity also presents options and value for future uses of the world’s genetic diversity. There are policies at national level in Uganda to promote biodiversity conservation and some of the entry points have been wetland ecosystems, forests and conservation of natural surface water bodies. Kampala is lined with extensive wetlands that connect the hills of the city. Though there has been massive encroachment and changes in the wetland ecosystems there is matching effort to conserve the wetlands ecosystems.

But planning for infrastructure needs of a burgeoning population presents challenges of conserving biodiversity. For example, sewage management and treatment plants have been established in the wetlands as the considered best sites for locating such infrastructure. But this comes with loss of biodiversity and ecosystem changes. This is due to the decentralization of treatment facilities that moves away from the traditional central sewer systems that have often transported sewage for long distances to central treatment plants.

One response to sustaining some level of ecosystems and biodiversity is the promotion of decentralized sewer systems that can take advantage of the local resources and purification systems using the natural environment. This has potential for improving infrastructure access and efficiency, but also biodiversity conservation.

The role of planning and design

Moving from ecology in cities to ecology of cities provides an opportunity for sustainable city-regional development. But this will have to address the challenge of jurisdictional and territorial responsibilities, since urban ecosystems do not necessarily follow the administrative boundaries.

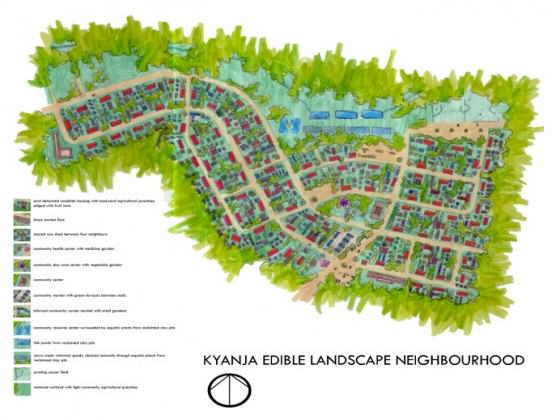

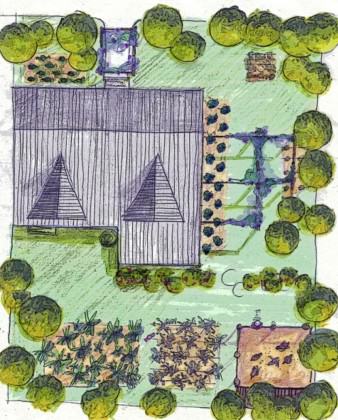

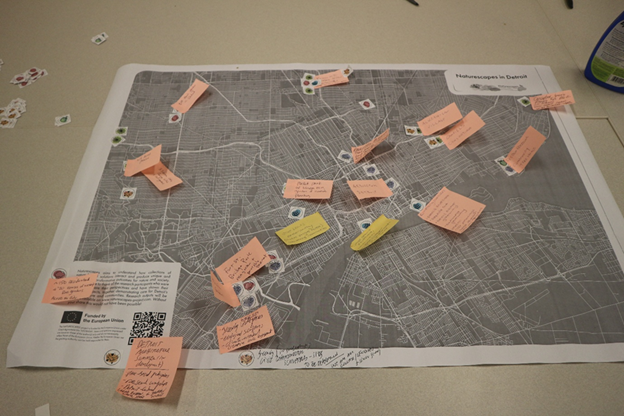

Even when natural systems like wetlands form the boundaries, there is a challenge of responsibility for biodiversity along the administrative boundaries. One way to optimize the ecosystem services within the city-region is through spatial planning for enhancement of the ecosystem services as a strategic intervention at city-regional scale, compared to the practice of piecemeal planning at neighborhood scale (Lwasa 2013). This requires consideration of the interrelationships between built environmental components with biophysical systems within city-regions. The most challenging consideration is to related to distant relations that cities have with other regions. In Kampala, some steps have been taken to introduce in planning practice design principles that can promote ‘urbanscapes’ with biodiversity and ecosystem functions. As shown in the pictures below, planning at neighborhood scale can also be an entry point for sustenance of urban ecosystems.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Kampala like many other cities of Africa can be looked at with a different worldview. That which differs greatly from other cities is characterized by patches of built form interwoven with smaller patches of nature.

This article argues that the form presents distinct ‘urbanscapes’ in which interactions of the components is important. The interrelationships between urban and peri-urban agriculture in promoting these interactions as well as biodiversity conservation is an important feature of the ‘urbanspaces’, though the conservation can be considered as minimal.

Kampala relates with the hinterland through resource flows but has also distal linkages with other regions to which it is not physically connected. The resource flows contributes to the understanding of stocking of materials and nutrients that influence urban nature but also the complex urban ecosystem. The relations are bi-directional because there are also outflows from the city to the hinterland.

The challenge of determining an urban nature which promotes biodiversity and functioning of ecosystems will remain as urbanization occurs but the role of planning and design is critical in maintaining some level of ecosystem services within which biodiversity conservation can be promoted. Kampala has taken some steps through a city-region planning approach but it is important to note that this will not be the only solution to an urban nature that is sustainable.

Shuaib Lwasa

Kampala

References

Leave a Reply