Ecologists who study how ecosystems change over time know there is a balance between resilience and adaptation. Resilience is a measure of how long it takes for an ecosystem to return to a previous state. For example, how many decades will it take for a forest to regrow after a fire? Adaptation is the transformation to an alternative stable state, better suited to the prevailing conditions. If the forest burns again, and then again, a meadow may replace the forest.

Ecologically speaking we need both forests and meadows. As a scientific matter we don’t prefer one over the other. With cool precision we measure which species gain and which species lose when a fire burns the forest down.

It is difficult to bring the same level of equanimity to the damage wrought by natural disasters on built ecosystems, that is, the communities where people live and work. Although of a different kind, cities also have dynamics of disturbance, resilience, and adaption. Part of what makes cities like New York so fascinating is the on-going changes within and among the city’s neighborhoods, unrolling across decades, even centuries. At the same time when sudden, catastrophic changes come, no one likes to see the human toll of suffering and loss associated with events like Hurricane Sandy, just over year ago.

Thus we have the Catch-22 of Resilience. As a larger community, we know that the city must adapt over time to changes in the environment, whether that environment is defined ecologically, economically, or socially. But when it comes specifying those potential alternative stable states, the loudest voices are the people who lost the most, and what they want is exactly what they had before. Who came blame them?

The catch is after natural disasters there is a rush to “rebuild the familiar,” as some scholars described the process in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. We can see it in many places up and down the coasts of New Jersey and Long Island today, and in parts of New York City, where largely the decisions about what to do have been left to individual property owners, some of whom had support from private insurance (if covered) and government intervention (if not). Most people, quite naturally, don’t want to move. Most wish that Sandy had never happened and that future storms won’t ever come back. Few anywhere want to tell them different, even though the scientific writing is on the wall.

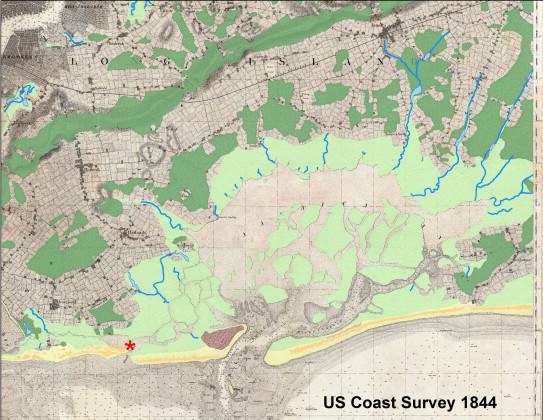

Unfortunately the realities of climate change mean living on a barrier island or atop filled coastal wetlands is becoming less tenable than it once was. Sandy was not the first, nor the last severe storm, to threaten New York. At least four hurricanes have made on direct hits on New York City over the last 400 years, while marsh sediments record numerous large overwash events extending back to at least the 1200s. Severe nor’easters are more common than hurricanes and can have storm surges of 6 – 8 feet. Climate change predictions for New York City suggest the future will see warmer temperatures, increased precipitation, and rising sea levels, not to mention, fiercer weather. There is every reason to believe that conditions will continue to change.

To break out of the Catch-22 of resilience, we need new ways to reconcile the democratic process with the reality of climate change, not only in areas vulnerable to hurricanes, but also in areas where fires, floods, and tornadoes occur.

There have been some interesting starts after Sandy. The public sector responded robustly, with major reports delivered at Federal, state, and city levels all within a year of the event, full of language promoting resilience. The very first recommendation of the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force (2013) is: “Promoting resilient rebuilding through innovative ideas and a thorough understanding of current and future risk.” To develop those ideas, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Rockefeller Foundation launched “Rebuild by Design”, commissioning ten “world-class, interdisciplinary teams” to develop “transformative planning and design approaches” after Sandy. Teams presented their first set of ideas around the anniversary of Hurricane Sandy in late October 2013. The US Army Corps of Engineers launched its own studies to promote resiliency of the North Atlantic coast, taking advantage of the large amounts of sand they dredge and move every year around New York Harbor. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration created “Digital Coast” a website designed help people “turn data into information they can use,” including county-level reports, a sea level rise and coastal flood impacts viewer, videos and a blog.

While important, these efforts focus on traditional models of public engagement, where experts create knowledge (like flood maps) or ideas (like novel architectural designs) that are subsequently communicated to the public. The public is conceived of as recipient, not a participant, in the process of understanding what resilience and adaptation means. That’s a problem. Researchers who study how the public understands science question whether the “Big Expert Speaks to Passive Public for Their Own Good” mode of knowledge creation really works, especially when changes in public behavior are necessary. More effective, they find, are shared, interactive modes of knowledge production, especially when dealing with complex, interdependent environmental problems, on the interface between science, society, and policy, like – you guessed it – “Big Storm Strikes the Shining City by the Shore (Again)”.

What does this mean for those of who care about nature in the city? It means that we need to take nature seriously in all its aspects. Yes, seeing redtail hawks in love, nesting on the ledges of apartment buildings along Fifth Avenue, is wonderful. But nature has its darker sides too. No matter how much we treasure our deeds of property, the fact remains that the wind and the waves do not care one iota for scratches on paper. Nature’s first and last lesson is no part of the universe is meant to last forever. We can see transience as a tragedy, or we can embrace it as part of the Earth’s dynamism, but in either case the place where adaption really needs to occur is in our hearts and our minds. Our social response after natural disasters like Sandy measures not only our toughness and resilience, but also our capacity for wisdom and growth.

In New York and elsewhere, restoring nature’s defenses (beaches, sand dunes, salt marshes, riparian corridors, bioswales, green roofs, etc.) will help us be more resilient to the next storm. Sandy has opened huge opportunities for nature restoration along the Atlantic shoreline. Nature can protect us through systems of its own making and ones we help nature make. The natural world overflows with advice about the strategies we can take to avoid and survive the next disaster. Even how not to have disasters.

But being resilient is not the only, or even the main, reason why nature in the city is important. Nature in the city is important because it enables us to see alternative ways of being, in our place, in our environment, in our cities, in our lives.

Eric W. Sanderson

New York City

Hi Mr. Sanderson,

I really enjoyed your article on adaptation and resilience. The two words are thrown around these days with such a wide range of meaning that I often have to step back and ask ”which form of resilience or adaptation is the author talking about?” The meanings tend to mean very different things depending on whether it is being discussed on a federal, state, city or community level. I think that broader, more agreed upon definitions of the terms, like the ones you provided, should be distributed throughout each scale.

I do want to briefly challenge one thing you wrote in your article. When describing the reaction after a hazard, you wrote that “the loudest voices are the people who lost the most.” While I cannot speak for Hurricane Sandy, post-Katrina, not very many people heard the voices of those who lost the most. In terms of rebuilding the familiar in New Orleans, the ones who lost the most were never able to come back to the city. They were not properly compensated by insurance, a vital aspect in resilience, and they were displaced around the country. A large amount of money was raised for artists to come back into the city, but the money was not evenly distributed to lower-income families.

On a more positive note, I do think that in New Orleans steps are finally being taken to grow and adapt, while keeping the familiar aspects of the city. Better storm management practice programs and an increased protection of coastal wetlands and barrier islands highlight a greater wisdom than the city and state once had in management.

Mr. Sanderson, it was a delight to read, especially the following statements which ought to popularized as a rallying cry!

“We can see transience as a tragedy, or we can embrace it as part of the Earth’s dynamism, but in either case the place where adaption really needs to occur is in our hearts and our minds.”

“Our social response after natural disasters like Sandy measures not only our toughness and resilience, but also our capacity for wisdom and growth.”

“The natural world overflows with advice about the strategies we can take to avoid and survive the next disaster. Even how not to have disasters.”

Yes!