While we have been focused on the nature of cities in cities and its sublime paradoxes, one could perhaps also enlarge the city nature question to reflect on the gradual urbanization of planet Earth. Whether it is global appropriation of Earth resources by humans — human activities now appropriate nearly one-third to one-half of global ecosystem production (Foley et al, 2005) — or the concentration of Earth’s resources and energy in cities, cities and thus their dwellers have enormous footprints and thus embedded nature from afar in city-infrastructure (see a previous Pincetl blog here).

This, I would argue, should now also includes how nature outside city limits gets dramatically altered with exurban development. Exurban development is not suburban development. It is the house on 5 to 20 acres, surrounded by either public land, or large ownership parcels that are relatively undisturbed. Land use rules and the availability of cheap (relatively) fossil fuel have enabled people to live in far-flung places and commute long distances into urban centers for employment. Not all of these exurban dwellers are affluent, but living outside of the city and the suburbs is a clear choice. And they bring with them a “city nature” spreading it along a city to exurban gradient — manicured lawns, non native ornamentals, and most of all, defensive spaces as I describe below.

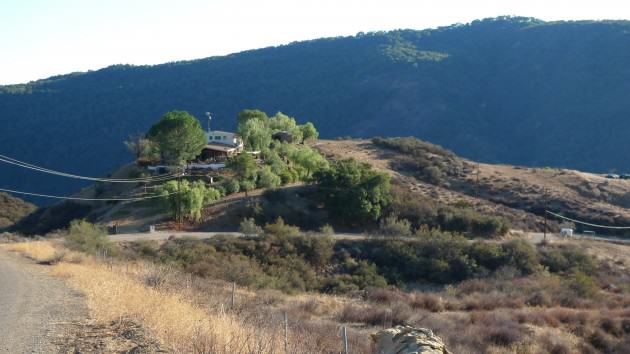

Here in Southern California where I live, I see the ravaging impacts of exurbanization on nature all around when I travel outside of the city itself. Unless the land is protected, like in National Forests, land continues to be developed and urbanized even in far-flung places. There are still many pockets of private land in the National Forests, and inholdings in large parcels. Alluvial fans, some of the best land for ground water recharge and urban–non urban buffers, continue to be developed due to their beautiful views. Because of our region’s fire-prone and fire-dependent ecosystems, when humans build dwellings in the exurban countryside it sets of a vicious circle of nature destruction. To build, there must be vegetation clearance around the home (unless it’s a suburb), and that now must be 300 feet around the dwelling. This is required by county fire departments, and fire insurance is predicated on complying with clearance requirements.

Vegetation clearance is just that: tabula raza, dirt. Increasingly rare chaparral and coastal sage scrub vegetation is removed for “fire safety”, creating disturbance conditions that favor Mediterranean grasses. Mediterranean grasses, in turn, burn more frequently and more easily than chaparral, and increased fire frequency in chaparral — a fire dependent ecosystem — stresses its ability to recuperate and engenders system change.

And the cycle reinforces itself. More fire (due to human intrusion and fire clearance that enables more fire prone grasses to grow) undermines the ability of indigenous vegetation to come back, which leads to more fire and more clearance.

Expectations of a safe, fire-free environment, brought to the fire-prone countryside by city folk, means the destruction of the very nature one would think they have escaped the city to enjoy. Many millions of dollars are spent protecting these homes, despite their bulldozed perimeters, because the truth of the matter is that fires in this part of the world are wind driven. They can easily jump 300 feet, and embers have been known to travel much, much farther. Often these same homes have trees all around them — there is a 300 foot buffer to the chaparral, but the houses themselves are closely surrounded by vegetation — perhaps to buffer the views from the scarred landscapes all around. Trees are, of course, akin to Tiki torches once the embers touch them, and the house is next. There is a great deal of discussion currently about revising building codes to make dwellings less fire prone — no open eaves, no wood shake roofs and so forth. But forbidding building in fire prone landscapes is not part of this discourse.

So what is driving this madness? A number of factors, including old subdivisions plotted at the turn of the 21st century and vestigial parcels claimed under the Homestead Act still exist and are seen today as great opportunities to develop for pastoral living. Weak land use regulations are another reason, and a remaining belief that developing beyond city limits is cost free. Thus, private property rights trump common sense and county budgets, and the landscape is the sacrifice zone for continued individualistic preferences for country living and long commutes (Pincetl et al. 2008).

And there are other impacts. Roads are built to provide access to the dwellings, creating further habitat fragmentation and fire hazards. Roads disseminate more non-native invasive and weedy species, accelerating the flammability of the landscape and thus the transformation of native habitat. Above ground power lines (much less expensive) also increase fire risk, and there is more pressure on water resources either due to well-drilling or water system expansion. With irrigation of yards for these exurban houses, there is run-off, often contaminated with fertilizers and pesticides. If the homes are on septic systems, they can contaminate soils and water. Exurban living must have the same amenities of any urban living, and more: privacy, space and the investment of many more resources to make it possible to live so far out. This includes infrastructure — made from petroleum products, plastics, minerals, timber — extracted from nature to begin with.

Not only is indigenous nature impaired and changed, but the resource intensity is high of such development. These exurban dwellers expect city-like services like fire, medical, sanitation and trash disposal, maintained roads and reliable access to where they need to go though rarely are those costs internalized to the individual home builder or purchaser. Rather, they are borne by society as a whole, and by, most especially, nature.

Exurban development continues, eroding habitat and landscapes. It makes for a continuum of “city nature” from the downtown core outward. In Southern California fire clearance is perhaps the most visible impact of that continuum, but habitat fragmentation, pollution and dramatic landscape transformation can be found across the U.S. Often exurban development takes place in vernacular and unprotected landscapes, carrying with it the characteristics of suburban living — the lawns, shrubs and trees, full blown energy and water use of more urban dwelling — but having an outsized impact and cost.

The curious thing about this phenomenon is that many of the dwellers of these far-flung places seek quiet and nature. They do not wish to live in the hustle and bustle of the city, the noisy, dangerous, populated city. Yet the transformation of nature they bring with them means they have urbanized the countryside. Such alienation from the city engenders changes far beyond the individuals themselves and raises questions about how to build better cities, more livable, humane and beautiful places such that there is less desire to transform our ever fragile and disappearing landscapes.

Stephanie Pincetl

Los Angeles

Leave a Reply