Another revolution the “ecological revolution” is required to go back and live in co-existence with nature.

Recently I have been to Auroville, an experimental universal township in Tamilnadu and Puduchhery of southern India. This was founded in 1968 by Mirra Alfassa known as “The Mother”. Auroville came to be known as a global village, as the prime motive behind this project is to demonstrate that people all over the world can live together in harmony. The project has received the endorsement from the Government of India as well as UNESCO. This village can accommodate a population of around 50,000 in the future. What struck me is the design.

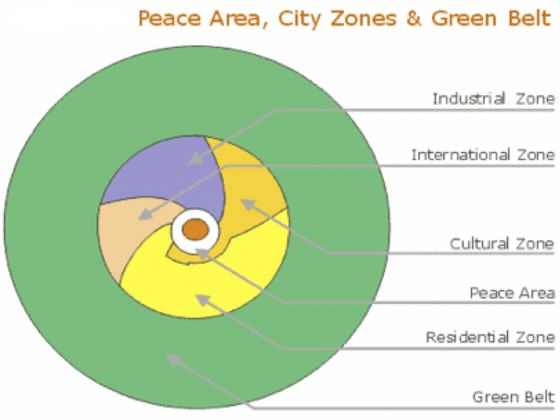

The village area has been divided into three concentric zones. The inner most is the core is the peace area. The area also has a lake to serve as a ground water recharge area. An adjoining circular area is divided into residential zones comprising 189 hectares, a zone for green industries comprising 109 hectares, an international zone (74 hectares) for a living demonstration of human unity, and a cultural zone (93 hectares) for research and other activities. The outer ring is the green belt, at present comprising 405 hectares, which has been successfully transformed from a wasteland into a green ecosystem. This zone has organic farms, dairies, orchards, etc., is also meant to be a barrier against urban encroachment, and finally meant to offset the human footprint. The village also extensively uses solar energy and has designed the buildings in such a way that they consume less energy.

Auroville is categorised as eco-city or sustainable city. Several examples of eco-cities exist in the world. Before the word eco-cities became fashionable in the modern era, India had several such historical examples.

Auroville is remarkably similar to what Kautilya has suggested way back in the fourth century BC on how a town or city should be planned. Kautilya is regarded as the father of political science. First and foremost, unlike the emphasis on GDP, the productive capital, Kautilya clearly recognised the role of forests, water bodies, and mountains etc as frontiers and collective wealth. The arthashastra recognised that waste (pollution) must be disposed in a proper way so as not to affect the environment. Arthashashtra suggests that the city be divided into four concentric circles. The main city is located at the centre and should have perennial source of water. Surrounding this central city are the villages located amidst the mixed land use — pastures, agriculture. Forests for recreation and economic benefits formed the outskirts of the settlement. The forest based industries are suggested to be located adjacent to the forests and settlement area. The forests in wilderness formed the outermost concentric circle and these have to be protected. These forests were occupied by tribes with traditional knowledge and enjoyed de facto rights on the forests.

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science Vastu shastra is entirely devoted to the science of architecture. Vastu shastra is a treatise on architectural planning, construction and design and emphasizes the right selection of the site given the nature of slope, colour, strength of soil and the direction of the plot. Vastu emphasizes optimal utilization of five elements: earth, water, fire, wind and cosmic space for harmonious living. The key contention is that when we build something we are interacting with the positive and negative forces of nature and it is vital to have a net positive energy flow (called bio flow or Prana).

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science Vastu shastra is entirely devoted to the science of architecture. Vastu shastra is a treatise on architectural planning, construction and design and emphasizes the right selection of the site given the nature of slope, colour, strength of soil and the direction of the plot. Vastu emphasizes optimal utilization of five elements: earth, water, fire, wind and cosmic space for harmonious living. The key contention is that when we build something we are interacting with the positive and negative forces of nature and it is vital to have a net positive energy flow (called bio flow or Prana).

Depending on the shape of the plot and its size, several plans called Vastu Purusha Mandalas divided into four concentric zones were suggested. The innermost zone is called Brahmastana, which is the place for total awareness. The next three circles in order represent Daiva (enlightenment), Manushya (consciousness) and Paisacha (grossness) respectively. The Brahmastana is always occupied by a temple or a palace, and the construction is suggested in the second and third zones. The ancient Indian cities of Pataliputra and Takshasila were constructed based on Vaastu principles. The modern Indian cities of Jaipur and Chandigarh and the temple cities of Tirupati and Madurai also follow Vastu principles.

So the history repeats itself. Now we have reinvented the same old philosophy of living in harmony with nature through the name of eco-cities or sustainable cities.

What are the key attributes of eco-cities? These cities are designed as follows:

1) Require minimal input from the rest of the world

2) Transfers minimal externalities to the rest of the world

3) They produce their own food, water and energy

4) Rely on using local material and on the natural flow

5) Have more wilderness and open spaces

6) Use natural solutions for stabilising micro-climates and use renewable energy sources.

7) Ideally they are smaller in size requiring less transportation of goods and services

8) Eliminate all carbon waste

Transforming the existing mega cities into eco-cities may be difficult. However, building new eco-cities is quite possible. If we are successful in building the eco-cities, it is possible to make positive economic, social environmental and ecological impacts.

In this era of high population pressure is it possible to have zero carbon and ecological footprint? There are several cities in the world which are named as “eco-cities”. But do we have some certification process to validate the claims?

The reason why it is important to have this process set up is due to the ambiguity of the term “eco-city”. We live in the era of globalization, which involves goods travelling long distances. The trade happens due to comparative advantage. That is, if a product X costs less in country A than country B due to some natural endowments, it makes sense for countries to trade due to comparative advantage.

Now, if an eco-city limits its production and imports goods from outside the city zone, to whom should we assign the carbon and ecological foot print ? For example, a resident living in eco-city would like to consume apples, Kiwis or Oranges, but which are not grown nearby. He has to import apples, which involves some externalities. To whom should these emissions be attributed to? This may be same for the other materials which are not available locally say rice, wheat, vegetables, etc., or material required for building the eco-city. A resident in an eco-city may have to use textiles or leather goods which are highly polluting. To whom should this pollution be attributed? Are we also assuming that living in eco-city also means changing the consumption patterns?

In fact this is the situation in today’s era of globalization. We cannot think of ourselves as living in a Robinson Crusoe economy — a closed economy with no trade. We need to clarify the ambiguities surrounding the measurement of footprints associated with eco-cities.

Having few eco-cities might not make a very big difference to the world, as they still have to depend on the external world for things other than food, water and energy. However, this is nevertheless a positive change. But if we have several such cities connected with each other, it is probably possible to minimize their carbon foot print and ecological foot print.

Just imaging and designing an eco-city is not sufficient. We also need to change our mindset and attitude. This might require an “ecological revolution” to go back and live in co-existence with nature.

Haripriya Gundimeda

Mumbai

Thanks indeed for the article that sheds more light on reference back from the origin of civilization and how we have tried to mock the concept and being selfdestructive in many ways so to speak. We have progressively nursed a gated community culture. An artist village was designed with similar concept in CBD Belapur Navi Mumbai and people prefered buiding walls and fences around them than adapting to social sustainable environment. Your comment about connecting sustainable cities and community will need the change of mindset that has been the sole motto of legendary social representatives.. and legendary figures history as well as todays world…the reference to develop nuclear sustainable hamlet-development to sustain on its own is a ecological, social, economical political, cultural… revolution indeed !!

Himalee Padmakar

Thanks for your piece Haripryia. It is quite inspiring, and thoughtful. Is it really possible to change habits? Many people are doing so, I believe, in search for a self-replenish life in harmony with nature. Auroville is a terrific example. I know many Brazilians that have been there is different periods of time. They all have changed their lives in some way.