Local governments planted millions of young trees on urban streets throughout the United States during the first decade of the 21st Century. From Los Angeles to New York, large cities made prodigious investments in urban reforestation and wrote off the expense as a relatively thrifty way of dealing with some deep-rooted and long-lasting environmental problems that any municipality would be hard pressed to fix on its own. That’s great. If Chicago can’t make every eighteen wheeler barreling down Kennedy Expressway run on ultra-clean biodiesel, it can plant more trees to filter the soot that inevitably burps out of tailpipes on older freight trucks. If Boston struggles to prevent raw sewage from seeping into the harbor every time a thunderstorm inundates the local treatment system, it can cut more tree beds into the sidewalk to sop up rainwater before it cascades into a curbside drain. You get the idea. On their own, trees don’t solve the underlying causes of pollution, but they ease the burden of so many different dilemmas that it’s hard to quibble with any concerted effort to plant more of them.

Scientists put a good deal of research toward cultivating and testing trees that can hack it in the city, but even the hardiest species need help during their first few years living on the streets. Young trees need water. They need fluffy, well-aerated soil. They need mulch. They need their broken branches pruned to promote rapid callusing against infection. In short, urban forests are not unlike rural forests in that they rely on human labor to successfully meet human needs. Yet few cities in the U.S. can pay for all that hard work.

While planting trees by the hundreds of thousands is a significant one-time capital investment, it’s nothing compared to the ongoing cost of staffing an army of public employees dedicated to keeping those trees alive. While the expense of sustainably managing a rural forest often pays for itself in the form of timber, the indirect benefits of a thriving urban forest never transform into real dollars and cents deposited in municipal coffers. We can calculate the value of ecosystem services provided by a functioning urban forest—the tons of carbon emissions prevented, the gallons of rainwater absorbed—but those savings don’t reappear as a line item in the street tree budget.

Since street tree care doesn’t pay for itself, cities rely on volunteer labor to make ends meet. I dealt with the pros and cons of this arrangement in my previous contribution to The Nature of Cities, so I won’t go any further than to say this: if volunteers are at the front-lines of urban forestry, we need to stop treating them like auxiliaries for a non-existent army of municipal arborists. We also need to recognize that volunteers aren’t just unpaid employees of local government, subject to policies emanating from City Hall. Neighborhood by neighborhood, volunteers have different ways of dealing with their patch of urban forest—different ambitions, different strategies, different priorities. Some want more trees. Some want fewer. Some form tight-knit groups to systematically care for every tree. Some prefer a more relaxed, individualistic approach. We must find a way to empower every community to find its own unique and evolving style of doing urban forestry. Volunteers are in the trenches. The rest of us, working in government, academia, and NGO’s, have to figure out how to help from the rear.

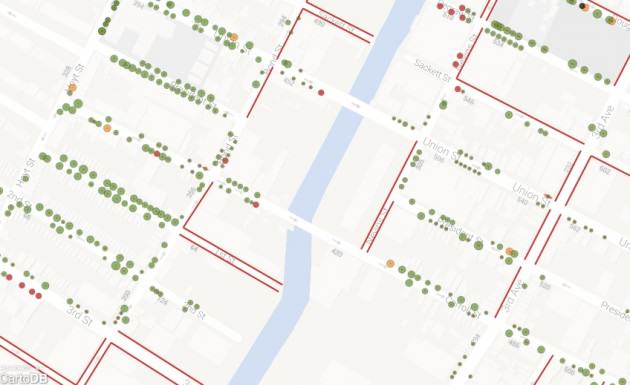

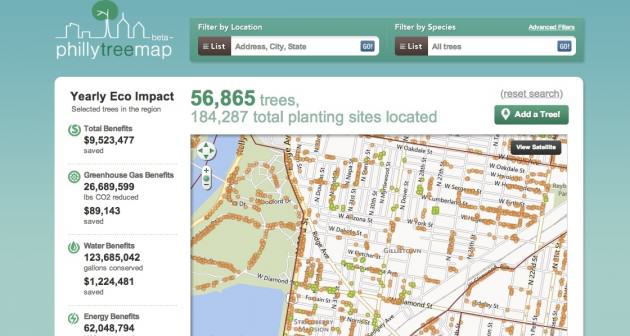

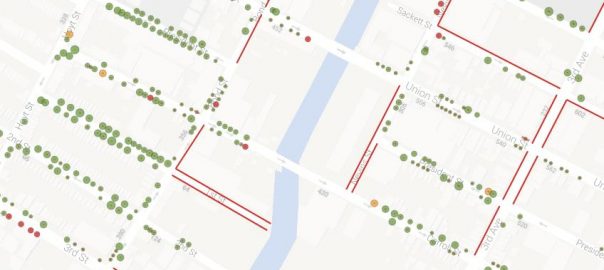

OpenTreeMap may hold some answers. An open-source website that invites the public to interact with detailed maps of urban trees, OpenTreeMap is already set up in San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, and throughout Great Britain. Earlier this year, the geospatial masterminds at Azavea launched a cloud-based version of the website that will be more affordable and accessible to small communities wanting to share their locally made tree maps with the wider world. This new version of OpenTreeMap allows volunteers to track the work they’ve done to maintain any individual street tree on any given day, from watering and pruning to enlarging a tree bed and installing a permanent guard around its perimeter. Volunteers click on a tree in the map, and up pops a little window where they can record their most recent activities. Later on, other volunteers can search for recent stewardship activity on the map, filtering out trees that have already been maintained in order to see where the most help is needed. The whole thing functions as a sort of self-organized volunteer mobilization system — except there’s no boss at the top giving orders, and volunteers are free to make their own decisions based on openly shared information about recent stewardship.

Some communities may not have a map-based inventory of trees to load into OpenTreeMap. No problem. The system itself allows users to drop new trees onto the map with the click of a mouse — or, these days, the flick a finger on a tablet. Alternately, for communities that want a more comprehensive approach, TreeKIT offers a low-cost and low-tech method for accurately mapping whole blocks of street trees out in the field (a quick explanation of how it all works is available here). The results are easily loaded into OpenTreeMap, and the hands-on nature of the process invites volunteers to go outside and discover a new affinity for their local urban forest. To date, volunteers working with TreeKIT have mapped more than 12,000 street trees on more than 600 blocks in New York City, and more work is planned for the summer of 2014.

Eventually, volunteers will want to know whether their stewardship efforts are actually having a tangible impact on tree health and longevity. Yet monitoring urban tree health can be tricky. Outward appearances can be deceiving. Sometimes there’s no way of knowing if a particular stewardship regimen is working until it’s too late and a tree is already dead. Sophisticated protocols and rigorous tools do exist for assessing urban tree health, but most are beyond the reach of the average volunteer. That’s where “open research” initiatives like the Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science and Photosynq come in. Both initiatives are busily developing affordable, easy-to-make, and easy-to-use environmental sensing technologies that can take the place of other, less accessible gadgetry. Public Lab recently unveiled open-source designs for a D.I.Y. spectrometer and near-infrared camera, both of which are potentially relevant for assessing tree health through measures of photosynthesis. Photosynq is beta-testing a similar low-cost tool for measuring “fluorescence and absorbance of photosynthetic plants and algae in a non-destructive way.” As tools like these become available, they can help volunteers make more refined assessments of their urban forestry efforts, empowering them to gradually tweak and adapt their practices based on good data about what does — and doesn’t — work.

Mobilizing, mapping, and monitoring — “Three M’s” for empowering volunteer urban foresters to do more impactful and rigorous work together, in their own style and on their own terms.

Philip Silva

Ithaca, New York

Leave a Reply