Walking in Bangkok is a messy experience. It is impossible to predict a change of grade or width of sidewalk under your feet. That is if there is a sidewalk. Similarly it is impossible to predict if the next building you walk past will be a shop house, condominium, bungalow, abandoned orchard, construction site, shopping mall or factory. Never mind the vendors, carts or motorcycle taxis. Or the many little pots filled with water, fish and lotus, or soil and flowering plants. It feels as if the whole city could be classified as mixed-use or just perfectly heterogeneous. Viewing the city from a car on one of the elevated highways, or from the skytrain it appears as a dense mix of tall and short buildings, sometimes in clusters, or almost a row but most often scattered. I find the assortment intellectually interesting, as when I walk I feel alert and engaged. From close up and afar, it is a beautiful mess. And my Thai students agree.

Last month I taught a workshop in Bangkok titled “Bangkok: Beautiful Mess” [See image 1]. It was pitched as follows: “This workshop engages the messiness of cities, in particular Bangkok. Students in this workshop love messiness, they enjoy its strange beauty and challenge those who want to tidy things up.” At the launch of the workshop I asked the students, why did you choose this workshop amongst the many they were offered? They said they were attracted to the word mess. So we spent eight days together, amidst the Bangkok Shutdown, exploring the nature of the mess. The students are third year undergraduate architecture from the International Program in Design and Architecture (INDA) program at Chulalongkorn University. The workshop is part of a yearly event called Design Experimentation Exchange (DEX). This blog post is a workshop report, which builds on two earlier posts, Patch Reflection that shared some new tools, and Urban Practice that was a seminar report. Together these are part of an ongoing project to explore ecological urban design practice, learning from the Baltimore School of Ecology.

Bangkok is changing fastest on the periphery — at the edge of the Bangkok Municipal Area and in the surrounding provinces such as Samut Prakan, Nonthanburi and Pathum Thani — all connected by the new ring road and an expanding skytrain and highway network. This is where the private-luxury-fast-car-air-conditioned life and all its urban forms is shared with the multimodal-shared-slow-car-boat-motorcycle-walking life of the village, farm, and temple. And so it was here that I focused our attention.

I also focused on the periphery because I observed an emerging pattern: megablocks form in the periphery in ways that were different than what I had observed in China and India. I also learnt from two bodies of research that I titled Bangkok Solid and Bangkok Liquid, as well as Grahame Shanes short history of the megablock [See references at the bottom].

The historical development of Siamese urbanism evolved from a tributary political system and a distributary water system and it has followed the Chao Phraya River from upstream to downstream. For example, Bangkok — a delta city — is the third capital, and is located downstream of the previous upstream capitals Sukhothai — a fan terrace city — and Ayutthaya — an island city (McGrath et al 2013). The Chao Phraya River as it forms the delta, meanders [See image 2: brown wiggly line]. Various khlong (canals) construction projects created north south shortcuts to enhance trade, shortening the distance for boats travelling from the gulf of Thailand to Ayutthaya, and later to Bangkok [See image 2: curved blue lines]. Other khlongs were built as east west shortcuts for defense — to allow the movement or troops [See image 2: straight blue lines]. The megablock for our workshop [See image 2+3: yellow square] is bisected by a busy waterway, Bangkok Noi Canal, an historical course of the Cho Phraya River. On the southern boundary of our megablock is an east west khlong, which is the site of a proposed fast boat dock that exits directly into the Bang Wa skytrain interchange. This is a brand new urban condition, where the elevated skytrain network and the khlong network are formally integrated [See image 2: orange line and See image 3: The image on the left shows the location and character of a proposed skywalk that connects the skytrain station to the boat dock. The image on the right shows the expanded BTS network for Bangkok that includes new growth areas (big green circles — Bang Wa is the one on the left), and the new fast boat (blue boat icon and small wavy blue line].

The future skytrain and fast boat city is embedded within a bigger and much longer historical transition from the slow water-based city to the car-based city. This is described as the shift from fluid khlongs to clogged roads (Sintusingha 2010). This is also a shift from the tributary political system of the Kingdom to the nation-state, and marks the subsequent decline of the water-body, an imagined national geo-body (McGrath et al 2013). It also marks the transformation from the distributary water system of the urban-agricultural delta from the cultivation of rice to a global network for exporting electronics and automobiles (McGrath et al 2013).

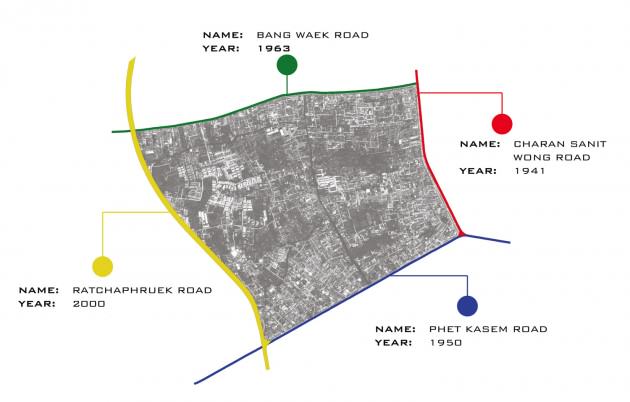

Bangkok grew historically along its khlongs, these long corridors formed a type of linear urbanism because canals were often filled in to create roads, or roads were built parallel to the canals. In addition thanons (roads) that ignored pre-existing land patterns were built to link distant provinces. Since the 1950s and today, rural land adjacent to new roads is developed as part of the car-based city. Soi (alleys or local feeders) are built to connect to old water-based temples, and villages. Soi are also built to create land development estates or housing development estates. The landowners build soi that follow agrarian land ownership patterns, therefore each landowner individually and varyingly participates in the piecemeal development of the their rice paddies into Bangkoks suburb (Sintusingha 2006). With the recent construction of the ring road and the new airport [See image 4: pink lines and pink zone] these radial corridors with their maze like soi are being increasingly interconnected at the periphery. Today a finer grain of connector roads that link old linear corridors have been built, and many more are proposed in the future [See image 4: red lines].

In Thailand megablocks form where these three different types of roads intersect in varying combinations: thanon, ring road and connector road. In India and China megablocks are formed by new city (Shanghai, China) or new town (Kolkata, India) development where each road is built at the same time, and rapidly (China) or incrementally infilled (India). In both cases land is no longer farmed as before. In Shaoxing I observed many piles of recently excavated soil located adjacent to farmer resettlement houses being temporarily farmed as kitchen and vegetable gardens. In Kolkata I observed former fish farms that are now grass-covered low lying lands used as foraging fields for villagers, and their roaming herds of cows and buffalos. In both cases existing residents leave, often under duress. Some stay under certain conditions, such as resettlement, as a urban village with varying upgrades, or as a type of non-urban area — a condition with less services, rights and privileges than adjacent urban areas.

These two linked methods for addressing rapid urban growth on the periphery of cities aim to solve congestion through decentralization in different ways. Thinking about city models is useful here [For an expanded description of city models for theory and practice see the McGrath and Shane 2012 reference listed below]. One way is to network existing and new cities (megalopolis city model is dominant in the Yangtze River Megadelta), another is to create a new legal entity, conduct a massive land grab on the periphery, and build a new town that includes all of the new big things that don’t fit in the old city: for example city governance, education, health, military or religious campuses, special zones for IT or industry, eco-parks, shopping malls, big box retail, and elite housing estates (fragmented metropolis is an emerging condition in the Ganges River Megadelta which is dominated by the megacity model). In Bangkok megablocks are not master-planned, and form overtime in a way that combines the big infrastructure moves of the megalopolis, and the big urban fragments of the metropolis with the water, plant, soil and micro-economy based livelihoods of the megacity. This is creating a messy but fertile urban form for thinking about inclusive and sustainable cities (might the Metacity become a dominant model for the Chao Phraya River Megadelta?)

For the long time residents of Bang Wa the new connector road is a boundary as it is ten lanes wide with no opportunities for pedestrian crossing, other than skywalks. It is this road, that formed a megablock in this area, enfolding and bringing diverse communities and places together. There is often a gradient of increasing privacy as you get deeper into a megablock. Typically the intersection where a connector, radial or ring road meets a long branching little soi forms a type of gateway that supports micro-economies. When congested, this street life with its many generations of street vendors makes for a difficult place to drive or walk if you are in a hurry. However the slow speed affords many types of transactions that support diverse livelihoods — one of many local systems of order which are deeply loved [See image 5]. In India and China the roads within the megablock are shaped in a different way. In the newest new town in Kolkata it remains to be seen how much of Kolkatas famous street life — maybe more messy than Bangkok — will be cultivated by everyone involved. Of note here are local syndicates which tend to exclude those that aren’t part of their patronage system, however they also create a powerful Occupancy Urbanism which bogs down mega politics while reconstituting real estate (Solly Benjamin 2007). In Shanghai state-led strategic planning protocols direct the design of inner block street life. Typically developers build an inner loop road to service each gated development, therefore creating an even more exhausting pedestrian situation than what Bang Wa residents are dealing with.

In the mebablocks of the periphery of Bangkok large land or housing development parcels are assembled from adjacent plots of farmland, which are typically found in the middle of the block. Grand gates, and long private roads service these middle-class residential enclaves which are often shaped like Thailand itself — with a narrow ‘neck’ and awkwardly shaped ‘body.’ New big roads are increasingly lined with suburban car-based attractions such as: nightclubs and restaurants with big outdoor terraces illuminated brightly at night, big box home furniture stores such as IKEA, and the newest urban form — a ‘community’ mall which consist of various air-conditioned pavilions in landscaped grounds rather than a big spectacular multi-level box. Sky train stations attract much high-rise condominium development increasingly connected by elevated walkways directly to the BTS or to adjacent shopping malls. At Bang Wa the riverside urban villages have become a nostalgic floating city backdrop for tourists as they speed by in colorful longtail boats for hire. Self-built pathways and boardwalk trails that connect houses within tightly built villages, and villages to farm land, khlongs, soi, schools and temples are being reorganized with changing ownership of land.

And so It is in this context that students designed urban design practices that might shape one megablock differently, and allow them to rethink the periphery of Bangkok. Below are six edited examples of the work and a conclusion to this workshop report.

Soi-Soi: shaping the messiness of our megablock street life in inclusive ways

Jom Praj Kongthongluck and Woody Sethavudh Siddhisariputra

Our idea is to minimize the soi (alleys) in order to provide more space for people to use. One reason for the famous traffic of Bangkok is because there are a variety of routes that drivers can choose to go. This diversity does not dilute the flow, but rather it causes congestion, as there are too many routes that lead to the same destination. So we dug into the typology of the soi of our megablock. We categorized them into three types that overlay each other: block (brown), ladder (red), and spiral (orange). We then highlighted all of the soi that lead to the same big street and to the temples — which are important community centers (green) [See image 6]. Soi in Thai means cutting off. So our project is called Soi-Soi or cut-cut.

Our proposal is to interrupt the soi with movable gates. This is not a shut down like a protest or the creation of a private enclave, but a break in the street system. We want to rearrange its mechanics. The result could be increased privacy for the local people, more plants and water gardens in pots, trellises for shade or food, and an increase in micro-economies such as motorcycle taxis, roaming cart shops, food vendors and expanded areas to accommodate temple festivals [See image 7].

Drift: shaping canals so local, express and excess water life can co-exist

Peachy Pitchanee Sae tung and Sarar Punnarungsi Temswaenglert

In Siam urbanization water was very meaningful to our lives. People used water for transportation, drinking, washing clothes and dishes, and cooking. Today the rivers and canals are gradually disappearing. Not physically disappearing, as they still exist, but visually as they become invisible in the shift from water-based to land-based urbanization [See image 8]. In our megablock we observed that Khlong Bangkok — the main canal — is only used by tourists in speedboats or for people who use it as a water expressway. These boats create many waves as they speed by. The smaller canals that are perpendicular to this turbulent water space have been ignored for some time.

Our idea is to support small groups of adjacent property owners to collaborate and build new connections between these smaller canals: to create a local economy from a secondary and less dangerous water movement network. These new canals could have water gates and weirs that connect to orchards revaluing their corrugated landform as productive monkey cheeks (micro water retention systems). Some orchards might form a shady canopy for floating markets. Drift is a spatial strategy but it is also a perceptual image, one that brings forward the smell of romance during dinner while enjoying sunset reflections. Old teak houses and new elevated buildings are home stay or apartments. These new neighbors who commute to the city on the fast boat, now live with slow local water too [See image 9].

Seasonal tung: forming parks within the heterogeneity of the inner block

Gun Donrawat Jantarumporn and Punch Nattan Limpanyakul

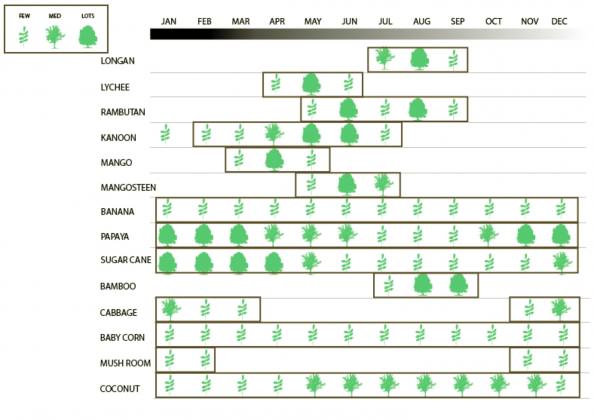

We are the plant group and we don’t want to destroy the mess of the Thai culture but be adaptive to it. Our idea is that fruit plants can act as the catalyst for parks, a spatial type that is lacking in our megablock. Learning from our fieldwork we studied the many different types of land cover mixes within our megablock. We then created an animated drawing to help us imagine how different vegetation systems might be engaged among the existing communities, as a living way to organize area [See image 10]. There is a trend in the periphery of Bangkok where agricultural land in the middle of the megablock is the last to be in-filled with new buildings, such as gated middle-class housing developments. Typically those areas closer to the fast roads get built first. Seasonal Tung (field) is an idea where the owner opens up the remnant farmland as well as front yards and backyards for public use.

Our idea follows a coffee shop model. You are expected to buy a cup of coffee, or a bowl of noodles for example, and then you can hang out all day. This is something that happens all over the city. During the fruit harvest, or whenever the owner wants, the park is closed. People then explore their neighborhood further, moving with the seasons and becoming closer to plants [See image 11].

Shared privacy: dead ends as gates that sustain existing communities

Kanoon Prechaya Punyakham, Imm Pawika Thienwongpetch and Jean Rudiampai Kuonsongtham

Our group focused on dead ends, which are located throughout our megablock. We observed two types. First are shared, and often self-built alleys, which provide access to private homes in tightly built villages. Second are new, and gated developments, which have one fancy entry gate with roads and sidewalks that again lead to private homes. In this case the homes are often large villas, or townhouses surrounded by walls. Both societies desire privacy. Moreover, we noticed that abandoned farmland — an indicator of future gated developments — lay in between many of these two dead ends [See image 12].

We saw this as potential. For an expanded private space that supports peace between people from each side. Shared Privacy is an idea that transforms horizontal sprawl into vertical living to create new model of urban form: a vertical suburban condominium in a monkey cheek. This is an idea that acknowledges flooding as a part of urban life. It is also an idea that supports existing communities, offering an expanded environment for living within the urban periphery a place where increasing congestion and enclosure is imminent [See image 13].

Bangkok on top: expanding the multi-level city

Khim Pisessith and Grape Nalintragoon

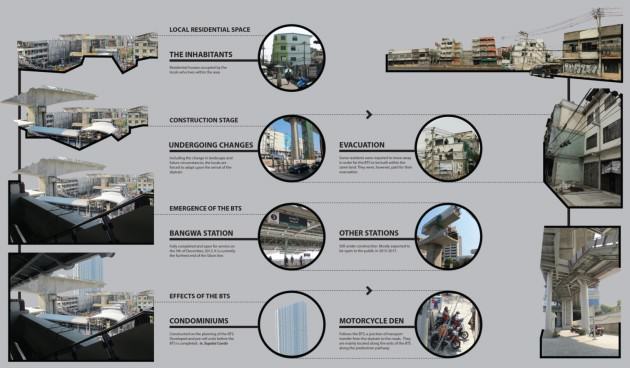

Our project is a system of multiplying messy street life activities that occur on the ground vertically. In our fieldwork we investigated the elevated BTS and MRT train lines with their skywalks, and new ferry pier inclusively. We stumbled upon several types of urban actors that had influenced and were being influenced by prominent places: such as a university, a hospital, and most distinctively, the under-construction condominiums. We also noticed that shophouses — a flexible and resilient urban form — were being demolished removed in blocks in order to provide spaces for condominiums or to widen the roadways. [See image 14]. Bangkok on Top offers a way for the “old settlements” as in the shophouses and the “new settlements” being the condominiums and other expanded institutions to coexist.

We asked what if the condominiums are built one block back? That is one block away from the main road, and is connected to the skytrain via a walkway, which links to the rooftops of the shophouses? [See image 15]. This keeps a vibrant street life on the ground level, as the shophouses have a mix of retail and residential and the condos only have parking. It also makes for a lively roofscape, multiplying and distributing the retail across the neighborhood, rather than in one big shopping mall, a trend at the other BTS stations. Our project aims to scatter perception in the multilevel city, and to create a complication of method, which supports inclusive messiness to the messy city that we all adore [See image 16].

Non-place some-place: forming mid-block communities

Tarn Chanaporn Sutharoj and Fon Thanwarat Petchote

We analyzed two roads, which are Jaransanidwong Road and Ratchaphruek Road. Both roads have their own characteristics: the Jaransanidwong area is a dense, slow, congested and friendly mess but Ratchaphruek is loose, fast, and alienating [See image 17]. It is a Non-Place that we wanted to make into Some-Place. Our project therefore explores sharing activities to create a community within this new, and wide suburban road. We observed three new activities that come with this road: car sales and service, fancy sport clubs, outdoor pubs and restaurants which are brightly illuminated at night. We mixed these with existing activities such as shopping for vegetables, waiting for the bus, and crossing the street — it is long hike to cross the 10-lanes road by walking. The long distance between the people in terms of feeling and physical space us to our proposal to expand three existing pedestrian bridges into skywalk community spaces. These are an urban form produced through a negotiation with the new landowners. These new crossing and intersection spaces will benefit their business, and activate their parking lots while providing pleasurable mid-megablock pedestrian destinations, something that is lacking [See image 18].

Conclusion

Reflecting on the workshop, which was the first urban design experience for all of the students, I can imagine two shared directions that this research might be advanced. First is to further understand the nature of the people that are rooted to this mess. What is their realistic agency within the city? As seen in many projects, their superadaptiveness can create amazing mutant kinds of physical and social spaces which are valuable in many ways. How might urban design practice support these types of public realms so as not to create a completely new city, but not to be nostalgic or romantic either? Rational modern strategic planning had a bias, it was assumed that cleaning things up was important because cities without order were characterized by ignorance and confusion, lethargy on the part of the people, which would be represented in their surroundings with crime, accidents, disease, juvenile delinquency, racial tension, waste and excessive cost, and potential political corruption, therefore planning of a type created in the 1960s was needed. Today this sounds plain silly, but still the nature of the mess could be supported and shaped much better.

A second direction is to draw more, to learn to see the dynamics of all of the periphery megablocks in relation to other changes occurring in the delta. Our workshop has found ways that one megablock might be valued as a basic urban element that keeps its messiness in patchy, reflective, playful, and inclusive ways. Every urban condition here is seen as having potential: the maze-like nature of the soi, latent water infrastructure, multi-layered sky-train spaces, shophouse street life, and the abandoned orchards with their fertile soil and little pathways that connect to small urban villages. The resorting of the delta by the state, particularly after the 2011 flood is occurring in ways that continue to ignore the water-body, privileging a solid imagination over a liquid one, and ignoring important cultural knowledge (Thaitakoo and Mcgrath 2008). Many megblocks are connected to canals and the expanding skytrain network. Might it be possible to open up a discussion with the irrigation department about opening flood gates during the dry season, rather than pumping? This would allow the fast boat network to expand. Might a water-body be created anew, moving downstream, but this time connecting to the ocean-body, a geo-body which disappeared in the sixteenth century but one that is also being created anew.

Victoria Marshall

with Yanisa Chumpolphaisal

Newark and Bangkok

References:

Bangkok – Solid

Sidh Sintusingha, “Sustainability and urban sprawl: Alternative scenarios for a Bangkok superblock,” Urban Design International, 00 (2006) 1–22.

Sidh Sintusingha, “Bangkok’s Urban Evolution: Challenges and Opportunities for Urban Sustainability,” in Megacities: Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability, eds. A. Sorensen and J. Okata (Tokyo: Springer, 2010).

Bangkok – Liquid

Brian McGrath, Terdsak Tachakitkachorn and Danai Thaitakoo, “Bangkok’s Distributary Waterscape Urbanism,” in Village in the City: Asian Variations of Urbanisms of Inclusion, Eds. Kelly Shannon, Bruno De Meulder, and Yanliu Lin, (Chicago: Park Books – UFO: Explorations of Urbanism, 2013) in press.

Danai Thaitakoo and Brian McGrath, “Mitigation, Adaptation, Uncertainty –Changing Landscape, Changing Climate: Bangkok and the Chao Phraya River Delta,” Places, 20.2 (2008), 30-35.

Urban Design Theory

D.G. Shane, “Block, Superblock, Megablock: A Short Global History,” in press

Brian McGrath, Grahame Shane, “Metropolis, Megalopolis and Metacity,” C. Greig Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen, The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, (London: Sage, 2012).

Solomon Benjamin, “Occupancy Urbanism: Ten Theses,” Sarai Reader: Frontiers, 538 (2007).

Group photo:

Leave a Reply