A lot of recent discussion around urban planning, resilience, and sustainable cities has included ideas about community engagement. How do we get the public more engaged in urban planning in ways that are effective — that honors good design, evidence-based science and community desires? Having decided that community engagement is a good idea doesn’t make it easy. My friend and colleague PK Das of Mumbai has been involved in a lot of public engagement around the expansion of open spaces, and he said something insightful. One the one hand, plopping a big plan with an elaborate drawing down in front of an audience is not exactly engagement — in fact, it can easily be a buzz kill. On the other hand, when I asked Das what for him was the biggest difficulty, he responded: “As a professional, it is resisting the temptation to try an control the proceedings; I need to relax and be a participant.”

So there it is. How can we meld expert opinion (plus facts and science) and non-expert opinion (just as valid, but different) in a way that honors and includes both?

I am very excited about engagement exercises that use simulation models as tools to get people talking not just about their opinions, but about the consequences of their opinions. Incorporating simulation models explicitly into community dialogues is an approach to this. That is, individuals or groups can sit down with a computer simulator of, say, how green infrastructure performs in storm water capture. The people can arrange green roofs, or parks, or street trees on the landscape and the model calculates for them how much storm water has been captured using their design. The science and expert knowledge are built into the inner workings of the simulator (the “black box”). Individuals can try out their designs and social ideas using the model as context, and have the model give some feedback about the how their ideas would work on the ground. Their ideas are taken out of the realm of unverified opinion and placed in a context in which their function, output, and outcomes can be compared. You might still prefer one type of design to another, but its performance could now be part of the decision mix.

I am very excited about engagement exercises that use simulation models as tools to get people talking not just about their opinions, but about the consequences of their opinions. Incorporating simulation models explicitly into community dialogues is an approach to this. That is, individuals or groups can sit down with a computer simulator of, say, how green infrastructure performs in storm water capture. The people can arrange green roofs, or parks, or street trees on the landscape and the model calculates for them how much storm water has been captured using their design. The science and expert knowledge are built into the inner workings of the simulator (the “black box”). Individuals can try out their designs and social ideas using the model as context, and have the model give some feedback about the how their ideas would work on the ground. Their ideas are taken out of the realm of unverified opinion and placed in a context in which their function, output, and outcomes can be compared. You might still prefer one type of design to another, but its performance could now be part of the decision mix.

Mannahatta 2409

A fantastic new example of such a simulator is now available in a testing phase (“Beta”) version. It is called Mannahatta2409 and is an outgrowth of Wildlife Conservation Society ecologist Eric Sanderson’s work to reconstruct what Manhattan island looked like in the year 1609, the year the Dutch arrived. Mannahatta2409 is forward looking. You can take any section of today’s Manhattan and redesign it, putting it parks, bike lanes, green roofs, streetcar lines, wind arrays, landfills, bigger buildings…almost anything. You can specify the consumption behavior of the residents in your simulation: average New Yorker, average American, “Eco-hipster”, etc.

Want to retreat from the shore and install barrier beaches along the periphery? OK. Want to compare street trees to parks in their storm water capture? Get to it. Want to fill Central Park with solar panels? Sure — great for carbon footprint, bad for biodiversity (don’t worry, eliminating Central Park as a public space means you won’t be Mayor of New York for long).

You redesign Manhattan, block by block, to your specifications and then the “black box” of the simulator calculates a variety of key sustainability statistics, such as energy use, carbon, water flow, biodiversity, human population size, etc. You can register at the website and make your own designs (or “Visions”) or just check out others (there is a library of them). Warning: there is a bit of a learning curve, but investing some time, with patience, is fascinating and greatly rewarding. The creators have plans to continue improving it, including things like learning “competitions” to find to best and most productive design ideas.

You redesign Manhattan, block by block, to your specifications and then the “black box” of the simulator calculates a variety of key sustainability statistics, such as energy use, carbon, water flow, biodiversity, human population size, etc. You can register at the website and make your own designs (or “Visions”) or just check out others (there is a library of them). Warning: there is a bit of a learning curve, but investing some time, with patience, is fascinating and greatly rewarding. The creators have plans to continue improving it, including things like learning “competitions” to find to best and most productive design ideas.

For example, Eric Sanderson created a Vision of the 14th Street corridor in lower Manhattan (the northern boundary of Greenwich Village). Using a combination of parks, trees, street cars, and bioswales, Sanderson redesigned the yellow zone in the image above to have higher population density and yet to require dramatically less energy. Sure, it’s a hypothetical exercise, but one that has enormous potential to demonstrate what is possible when we rethink how cities are put together.

Eric did this Vision on his own, but imagine gathering groups of neighbors to discuss neighborhood redesign. Or using it with students as an education tool (as the Manahatta team hope to do). Or…you get it, the potential applications are vast.

Check it out. Do this:

- Go to https://mannahatta2409.org/ (Note: it doesn’t work on Safari)

- Select “Existing Visions” and a popup presents a list of Visions that have already been created.

- Scroll to the right (with the right arrow); find and click on “Terra Nova 14th Street”, a redesign of the east to west length of 14 Street in lower Manhattan

- A box appears in the upper left; click on the little “i” button to see some information about the Vision.

- Click on “Environmental Performance” and then “Show Details” to see how the design (the orange bar in the histogram) performs compared to the current design of the street in 2010 (brown bar), and the how the place was in the year 1609 (green bar).

- Notice that this design has more people (higher density buildings) but emits dramatically less carbon and flushes zero storm water. Beware: no automobiles!

Note: A direct way to get to this Vision is https://mannahatta2409.org/?vision=9510.

Lidra storm water simulator

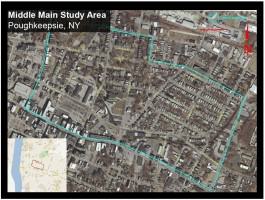

A group of engineers and storm water experts including Franco Montalto have produced a focused tool for storm water planning called Lidra (the site is still under construction). The thematic scope is more proscribed than Mannahatta2409, but it is geographically unlimited. Like Mannahatta2409, Lidra is a black box. However, Lidra focuses on models of storm water capture by various types of green infrastructure such as street trees, bioswales, green roofs, etc.

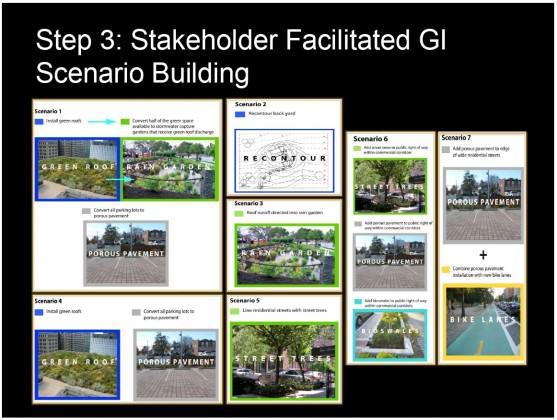

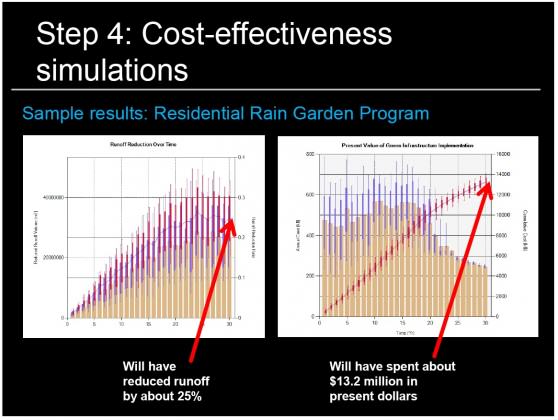

As a participatory planning tool, the idea is this. A neighborhood group convenes after having installed an infrastructure map of their area in Lidra. The group then can discuss how their want to design their neighborhood from a green infrastructure (GI) perspective, placing the various types of GI down in space: a green roof here, a bioswale there. The model then calculates and outputs the total storm water capture potential of the design and how much it would cost to build and maintain.

Does one person in your area want to invest everything in green roofs, while another thinks street trees are the answer? The model can help place the consequences of these alternatives in context (at least from a storm water perspective), making their relative outcomes easier to see, digest, and decide upon. Sure, there would still be decisions to make that are outside the scope of Lidra — aesthetics, access, equitability, and so on — but the model helps take at least some of the guesswork out of the process.

Does one person in your area want to invest everything in green roofs, while another thinks street trees are the answer? The model can help place the consequences of these alternatives in context (at least from a storm water perspective), making their relative outcomes easier to see, digest, and decide upon. Sure, there would still be decisions to make that are outside the scope of Lidra — aesthetics, access, equitability, and so on — but the model helps take at least some of the guesswork out of the process.

Participatory planning is difficult enough. Why not strive for apples to apples comparisons whenever possible? Simulation models such as Lidra have enormous potential to help.

All models are wrong — some are useful

All models are wrong — some are useful

There is a famous adage about models: “All models are wrong; some of them are useful.” The designers of Mannahatta2409 and Lidra have created tools that model various key elements of sustainable cities, and which allow you (or groups) to test drive designs and see how they perform, to compare them. They’re not perfect — they are not meant to be, they are for focusing on elements of a system — and it isn’t exactly “real life”, but as any thoughtfully and comprehensively created models do, they provide tools to think, compare, and come to a better understanding of how sustainable cities might be put together. They can take a little of guesswork and unvarnished opinion out of the important but difficult work of participatory planning.

These specific simulators are amazing accomplishments. And, I think approaches like this are a key element to the future of thoughtful and productive public engagement in urban planning.

What will it take to get more tools like this into participatory planning? I believe it will be key to get scientists and planners talking actively with each other about exactly what is needed as outputs of participatory planning events. I often hear people wonder how scientists and practitioners can work together. Working side by side to build participatory planning tools with foundations in science and data has enormous potential.

David Maddox

New York City

Nice piece David!

Lindsay,

I agree wholeheartedly. We have to make planning easy and cheap so that more people can get involved. To orient distributed greening efforts for maximum overall value, we need distributed participation of stakeholders with different value systems. In developing LIDRA, we tried very hard to create an easy, free, tool that has a lot of sophisticated stuff going on behind the scenes but without bothering the users with it… in the applications so far, we have scene the tool inform lots of different debates, ultimately with everyone involved feeling better informed about the opinions they have about what should happen…. We need more simulation tools that support the new kinds of multidisciplinary debates that cannot be avoided in urban greening efforts….

Franco

This is an excellent article, and I appreciate the highlighting of different tools used for different purposes and the focus on seeing consequences (especially with the inclusion of the cost forecasting) of individual decisions. Regarding your question, I agree that having planners and scientists talking more about what is needed out of participatory planning is key – planners often do not have the expertise to construct these tools and often not even the awareness that they exist.

However, I feel that a key way to get these types of resources into everday planning efforts will be through open source design and user-friendly scenario building tools that anyone can access. For example, in addition to paper-based map exercises, three of our projects at the City of Fort Collins are now using wikimap to gather feedback (example here: http://wikimapping.com/wikimap/FCBikes.html). Do you (or others on this blog) foresee a WikiMap version of this type of tool in the future? How, as planners and scientists, do we help shape that?