Cape Town sprawls beneath the majestic Table Mountain in the heart of the mega-diverse Cape Floral Kingdom. With 3.74 million inhabitants, it is South Africa’s second most populous city. Despite the obvious ecological stressors resulting from the city’s high metabolism and rapid expansion (ca. 1.4% per year), a spectacular richness of biodiversity survives within and around the city limits.

Early European settlers of the Cape quickly denuded the region’s small patches of native forest. To compensate for this loss, they undertook several waves of planting, primarily for timber, fruit and shade but also for aesthetic beauty and defence (see tree No. 11 below). Consequently, many of the heritage trees found in Cape Town today have been introduced, typically from Europe or other distant parts of the world with historical trade links to the Cape. Yet even non-native trees can be valuable, especially in terms of ‘cultural ecosystem services’.

This article is a sequel to an earlier installment, entitled, Trees as Starting Points for Journeys of Learning about Local History, published on 1 September 2013. In that article, I explored the historical, cultural and spiritual dimensions of a selection of remarkable trees found in the vicinity of Cape Town, South Africa. I suggested that such trees have distinctive personalities, reflected in the various anecdotes that we attach to them; that they shed light on the cultural value systems and economic priorities of bygone generations; and that they provide excellent starting points for journeys of learning about a city, journeys that have no fixed route or endpoint.

I argue that such trees deserve greater recognition and protection for their part in enriching the urban landscape.

Here follows a selection of additional Capetonian Heritage Trees

9. Van Riebeeck’s Hedge

Africa is the cradle of humankind. There is evidence of modern humans living 130,000 years ago in the Western Cape and at least 30,000 years ago in what is now Cape Town. Comparatively recently, in the late 1400s, European explorers began foraying into the Cape coming face to face with the region’s indigenous people: interconnected communities of San (hunter-gatherers) and Khoikhoi (nomadic pastoralists), collectively known as Khoisan. Each summer, the Khoikhoi would bring herds of cattle across the Cape Flats to graze on the slopes of Table Mountain. Delighted to find a reliable supply of fresh meat, the Europeans quickly established trade with the Khoikhoi, exchanging metal for livestock. The first transaction is recorded to have taken place in December, 1497, in Mossel Bay.

In 1652, when Jan van Riebeeck of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived at the Cape with orders to establish a victualing station, relations with the Khoisan took a turn for the worse. Essentially nomads without a written culture or bureaucratic governance system, the Khoisan did not have written title deeds. Accordingly, van Riebeeck contrived to deny the Khoisan their traditional land rights, provoking a revolt and ultimately bringing an end to a long period of reasonably friendly association (with some notable exceptions e.g. see No. 1, in Trees as Starting Points for Journeys of Learning about Local History). Cattle theft and bloody skirmishes became increasingly common. In 1660 Van Riebeeck ordered new defences to be built, including the planting of a Wild Almond (Brabejum stellatifolium) hedge around the perimeter of the settlement, encompassing an area of about 6 miles by two.

The Wild Almond is a member of the Protea family and closely related to the Australian Macademia Tree. It grows as much horizontally as it does vertically, posing an almost impassable barrier to cattle. Its wild fruits were harvested, specially prepared and eaten by the Khoisan. Today one can find remnants of Van Riebeeck’s Hedge on a leafy ridge in Kirstenbosch National Botanic Garden. There, a plaque reads:

For many, this hedge marks the first step on the road to Apartheid and symbolizes how white South Africa cut itself off from the rest of Africa, dispossessed the indigenous people and kept the best of the resources for itself. Our challenge in South Africa today is to dismantle the barriers erected in the past, share the resources equally and build a home for all.

10. The Namesake of the Palm Tree Mosque

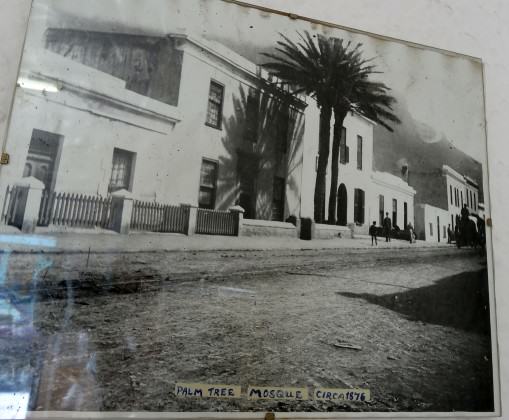

A raucous collision of colour where old meets new, tourists meet pickpockets, businessmen meet prostitutes, and drunkards meet drug-dealers: Long Street — the ‘beating heart’ of Cape Town — is not a savoury place. Yet skirting this canyon of intemperance, tucked among the busy restaurants, clubs and stores are architectural gems of great antiquity including one of the city’s most enduring and historic spiritual spaces: the Palm Tree Mosque.

Also known as the Dadelboom Mosque, it is the second-oldest place of Muslim workshop and one of the oldest substantially unaltered buildings in Cape Town (constructed c. 1780; second story added c. 1820).

Also known as the Dadelboom Mosque, it is the second-oldest place of Muslim workshop and one of the oldest substantially unaltered buildings in Cape Town (constructed c. 1780; second story added c. 1820).

Two tall palm trees (species unidentified) once towered above a small garden in front of the mosque. The garden is now pavement and only one of the original trees remains; the other fell victim to the fierce ‘south-easterly’ presumably in the early 1960s, as a framed photograph inside the mosque, suggests that a replacement tree was planted in 1965. Segments of the deceased tree’s trunk are seemingly used as stools inside the mosque.

In Islamic culture, palm trees are deeply symbolic: they appear around oases to signal water as a gift of Allah; they are said to grow in the Islamic paradise of Jannah; Muhammad built his home and the first ever mosque out of palm trees; the first muezzin would climb up palm trees to proclaim the call to prayer; and in the Quran (19:16–34), Jesus was born under a palm tree.

Under Dutch rule of the Cape, Islam could not be practiced in public. They banished one of the founders of Islam in the Cape, Tuan Guru (‘Mister Teacher’), to Robben Island where he famously wrote his own edition of the Quran from memory. Restrictions were relaxed when the British took control in 1795 and the free Tuan Guru soon established the Auwal Mosque (the city’s oldest mosque).

In the early 19th century, two freed slaves, Jan van Boughies and Frans van Bengalen, turned their backs on the Auwal Mosque after the former failed to succeed as imam. In 1807, they purchased the building which they would fashion into the Palm Tree Mosque. Records suggest that Van Boughies eventually owned 16 slaves, although some sources suggest that he only purchased them to set them free. Van Boughies died in 1846 at the age of 112, bequeathing the property to his wife under the condition that it would continue functioning as a mosque.

11. The Money Tree in Kalk Bay

Money may not grow on trees, but it often changes hands beneath their branches. In the sleepy fishing village of Kalk Bay in the southern suburbs of Cape Town, the Money Tree — a Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) — is said to have sheltered countless transactions.

From the late 1600s to 1850s, Kalk Bay — as its name would suggest — supported a lime industry burning locally abundant seashells in kilns. With the demise of that industry, fishing emerged as the village’s economic staple. After each day at sea, it was under the Money Tree, safe from driving rain or blistering heat, that fishing boat skippers would dispense wages to their crews. So too, traders known as ‘langgannas’ — a Malay word reflecting Capetonian ancestry — would gather around the Money Tree to purchase cartloads of fish. These they would lug some 30 km north to Table Bay, blowing traditional fish horns at way stations to announce the arrival of their commerce.

From the late 1600s to 1850s, Kalk Bay — as its name would suggest — supported a lime industry burning locally abundant seashells in kilns. With the demise of that industry, fishing emerged as the village’s economic staple. After each day at sea, it was under the Money Tree, safe from driving rain or blistering heat, that fishing boat skippers would dispense wages to their crews. So too, traders known as ‘langgannas’ — a Malay word reflecting Capetonian ancestry — would gather around the Money Tree to purchase cartloads of fish. These they would lug some 30 km north to Table Bay, blowing traditional fish horns at way stations to announce the arrival of their commerce.

Many of Kalk Bay’s ‘coloured’ residents survived the abhorrent Group Areas Act of 1966, receiving dispensation from forced removal. As such, Kalk Bay enjoys a cultural continuity unknown to other parts of Cape Town. However, decades of overfishing have dramatically reduced the size of the fishing fleet and the Money Tree now hangs rotting by the roadside, devoid of leaves, a skeleton of its former glory.

12. The Kindergarten Giant

A century-old Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) — indigenous to the east coast of Australia — radiates from a kindergarten in the University of Cape Town. Scores of children find magic and adventure in the deep boughs and buttresses of its roots. With a girth (trunk circumference) of 16m and a crown of 41m, it is also known as the Big Friendly Giant. However this giant is dwarfed by its sibling living just a few miles away in Claremont’s Arderne Gardens (see No. 13).

13. The Colossi of Arderne

13. The Colossi of Arderne

In the southern suburb of Claremont an extraordinary garden is home to some of South Africa’s most colossal trees.

The Arderne Gardens were established in 1845 by the Englishman, Ralph Arderne, who had amassed a considerable fortune as a timber merchant. His trade enabled him to collect plants from all over the world and soon his garden became famous for its exceptionally-beautiful collection of exotic trees. Ralph Arderne died in 1885, but his son, Henry, continued to develop the garden well into the 20th century. When Henry died in 1914 on the eve of the Great War, it is said that one of the original Norfolk Island Pines which is father had planted, synchronously withered and died. The garden then passed to a property developer who threatened to divide up the land into building lots. However, much of the garden was salvaged when, buoyed by a public outcry, the City’s Director of Parks and Gardens, Mr. A. W. van den Houten, persuaded the City Council to purchase the most important part. For the following 27 years, the garden was curated by M. A. Scheltens, who is said to have forgone several promotions in order to stay with the trees he so loved.

The Arderne Gardens were established in 1845 by the Englishman, Ralph Arderne, who had amassed a considerable fortune as a timber merchant. His trade enabled him to collect plants from all over the world and soon his garden became famous for its exceptionally-beautiful collection of exotic trees. Ralph Arderne died in 1885, but his son, Henry, continued to develop the garden well into the 20th century. When Henry died in 1914 on the eve of the Great War, it is said that one of the original Norfolk Island Pines which is father had planted, synchronously withered and died. The garden then passed to a property developer who threatened to divide up the land into building lots. However, much of the garden was salvaged when, buoyed by a public outcry, the City’s Director of Parks and Gardens, Mr. A. W. van den Houten, persuaded the City Council to purchase the most important part. For the following 27 years, the garden was curated by M. A. Scheltens, who is said to have forgone several promotions in order to stay with the trees he so loved.

Today, the Arderne Gardens remains one of Cape Town’s most popular green spaces, drawing sunbathers, picknickers, joggers and dog-walkers. Over weekends dozens brightly-coloured wedding parties pose for photo-shoots in the garden. One of the garden’s huge Norfolk Island Pines (Auraucaria heterophylla) features so regularly as a backdrop, that it is now colloquially known as the “Wedding Tree”. Of the many impressive trees in the Arderne Gardens, some are particularly huge. For instance, the world’s largest Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis) — native to the Mediterranean region — forms a giant corner-post of the garden, not far from the largest individual tree in the Western Cape and possibly South Africa: the Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla).

14. To be continued…

Russell Galt

Cape Town

Hi I live in Hout Bay on the main road, Cape town I have an oak tree, that is well in excess of 150 years, it has the usual aphid infection at this time of year and always bounces back. It is well in excess of 4 m in diameter and is otherwise healthy. We have a crazy new neighbour who wants it cut down, as it soils his cars. My wife is a well reputed horticulturist, who might kill. PLEASE HELP. a desperate pensioner.

076 151 7877 . We feel our heritage is being compromised

Dear Russell

I loved your article. Thanks!

May I ask your permission to use your photo of the old oak tree in Groot Constantia? It is for signage in the Leeuwenhof Estate about old oaks in the Cape.

You will be acknowledged of course.

Linette

lovit!

thanks Russell.

Do you perhaps know what trees grow in front of the Inn on Greenmarket Square. Are they oak?

Thanks in advance.

Loit.

Hello I love this article- thanks . Can anyone advise me what the process is to get trees protected. Development approval has been granted on a large plot near us and it contains some truly magnificent trees which I’m terrified will be cut down ??

Hi Russell – very intrigued by your story of the plaque at Van Riebeeck’s Hedge. I’ve tried to find a photo image of the plaque on the internet, but have been unsuccessful. There are quite few images of a plaque that explains why the hedge was established, but I can find none with the wording that you have quoted in your article. I wonder if the wording you have quoted is from a more recently installed plaque? I live in the USA, so not easy to travel to Kirstenbosch (sadly) but if you could help me find a pic or two of the plaque you have cited, please let me know. The words are quite moving! Thanks.

hi russell,

very interesting indeed

i have been looking for information on palm trees in architecture in south africa

there is hardly in homestead in south africa that doesnt have a palm tree.

do you have any idea why having a palm tree was so important?

Thanks , learnt so much , keep up the good work!!

Please advise me on what trees I can plant in my garden in Robertson, Western Cape.

Indigenous trees are what I’m looking for, to encourage birds as well as being water-wise.

Thanks so much

Hello Russell

I enjoyed reading your article. I grew up in Cape Town and have to see these places you make mention of multiple times. I always loved nature and what it has to offer but after reading this article I appreciate the trees in and around Cape Town much more. On my next visit to the Company Gardens I will be making new memories.

Can’t wait to read more of your articles.

Yours truly,

Emile

Dear Russel ,

I forgot to mention that the garden at The old Cannon Brewery is to developed to create an underground parking garage for 26 cars and store rooms…..I am afraid if this proposal is passed there wont be anything left of the garden or the trees.

Dear Russel,

I am thrilled to find you on the internet.

As an affected neighbor I have been informed that there are proposed plans to develop the gardens of the old Cannon Brewery with its century old trees some of which I believe were planted by Thibault .

While I am sure that Cape town City will not allow anything to happen to noted trees – it is the lessor trees and the garden as a whole that concerns me.

Gwelo Goodman was not only a gifted artist and architect but a passionate gardener and conservationist. His paintings of trees hang in galleries worldwide and due to his historical importance in South Africa House London.

He planted his garden in 1929 and is said to have planted a tree to bloom each month of the year. I have lived in part of his garden..now subdivided off.. for the past 30 years and can attest to the magic of the trees.

I would be so grateful to receive your informed opinion on this proposal before I make comment to council

with thanks Vanessa

Hello Russell

Your article is fascinating and very relevant to me at the moment. I am a painter in Cape Town and I am busy making a body of work for a solo show called ‘Trail’ which looks at the meaning of natural abundance in our South African neighbourhoods and cities. Green is the colour of wealth and priviledge. My show opens at SMITH gallery on the 23rd of Feb 2017 I was wondering how I could get you involved in making a comment about the Greenbelt area of Constantia with regards to it’s history of settlers, what they planted, slavery, forced removals etc. I am making a series of large ink works on paper that try to capture the feeling of natural abundance and privilege rather than to create paintings of landscapes. Can you tell me which trees were planted along the Greenbelt by the Dutch and English settlers and which mostly remain today? Many thanks, I am so glad I stumbled on your article.

Dear Russell

I am a new-comer to your work and ideas. I come from an art background and have little Tree knowledge. However, looking at your reply to Maria’s e-mail (25/3/16) regarding a 50 year old Ficus, it raises the question (for me), how responsible is it to advise the removal thereof and planting ‘indigenous’, without enquiring about what ‘problem/s’ it poses ? And… how does that it square with the comment in the second paragraph “yet even non-native trees can be valuable, especially….” .

I ask this as I am confronted by a situation in which I as member of a community organisation am being asked to support the removal of 3 Norfolk Pines of 32 years standing, (even though in my personal view they present no ‘essential’ or urgent problem) planted by the first three principals of a community school, to commemorate its re-opening, after dispossession of the previous school, in Newlands, under the group areas act.

Regards

Kanu Sukha

Hi Galliano, thanks for your question. If the oaks appear to be 330 years, then it could certainly could be true. A passage from Helen Robinson’s acclaimed history book, Constantia and its neighbours, indicates that the Commander van der Stel planted oaks himself: “After he had selected the site for is homestead, the Commander planted the oak and chestnut trees, which would line the avenues leading to his house. It was said that he carried a pocket full of acorns with him and planted them wherever he went.” So yes, it could well be true, in which case you are very lucky to have such historically-significant trees in your garden.

Good morning Russel.i live in Fernwood Avenue Newlands . On my property I have oak trees which I was given to believe were planted by Simon van der Stel and ran alongside the road leading from the Castle to Groot Constantia . Could you kindly confirm if this could be correct.

Many thanks .Kindest regards .

Galliano .

Hi Johan, thanks for your comment. There was a rich diversity of indigenous trees at the Cape. Perhaps the most abundant species were Cape Holly (Ilex mitis), Cape Beech, (Rapanea melanophloeos), Yellowwood (Podocarpus spp.), Wild Peach (Kiggelaria africana), Wild Almond (Brabejum stellatifolium), Milkwood (Sideroxylon inerme) and Keurboom (Virgilia spp.). Today most of the remaining patches of forest comprise jumbles of alien and indigenous species.

Hi Russel. When you write about the “native forests of the Cape”, which kinds of trees are you referring to? In other words, which tall trees can we call “the indigenous trees of the Cape” in for instance the Cape Flats, Table mountain slopes or the Helderberg basin, as they occurred naturally at the time of Van Riebeeck’s coming? Thank you so much for your article.

Johan van Zyl, Gordon’s Bay.

Hi Maria, thanks for your message and apologies for the delay in replying. I don’t know if my advice is still useful, but as far as I am aware, you are entitled to cut down unprotected trees on your land. The species concerned is a non-native deriving from Australia. I would recommend replacing it with a native tree species that will promote and support native biodiversity.

Thank you Marie for your kind remarks.

Hi Lynette, thanks for your message. I just checked on Google Maps. There are certainly eucalyptus trees there. However, I cannot discern the exact species without a closer look as there are around 900 species of eucalyptus.

Hi Russell, I’d like to know what the trees that line Rhodes Ave in Mowbray are called. Thank you!

We have a Ficus macrophylla tree about 50 years old -Can we chop it down or is it protected?

Your photos are great! Thanks so much for featuring our garden and sharing our unique story.

Thanks John, much appreciated. I’ll keep them coming!

Thanks Donovan for your kind and encouraging remarks. I must admit to having barely scratched the surface: I am yet to write about the Jan Smuts Oak in Kirstenbosch, the wind-sculpted trees on Sea Point promenade, the palm trees of Langa, the petrified tree in the Company’s Garden, etc. I’m also looking forward to writing about the camphors, oaks and mulberry trees of Vergerlegen near Somerset West. These will be the focus of my next article.

Hi Rusel,

I have lived o Cape Town all my life and have been at most all of the trees you feature, but many of the anecdotes you mention where not known to me and I greatly appreciate your effort and the love of these trees reflected in you posts. I look forward to more trees boo’s.

Caio

Donovan

Thank you very much for this article. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. I would love to read more about these heritage trees.