Nature Needs Half is a concept under consideration in the Capital Regional District (CRD)[End note 1]. Simply put, Nature Needs Half means saving fifty percent of an area’s lands and waters for nature. This concept recognizes the impact of humans upon the land, while also acknowledging that we need to share this planet with all other species.

Nature Needs Half is now being implemented across all jurisdictional scales, and in surprising and sometimes novel ways, in cities and countries around the world. The core concept of protecting half of an area for nature is being “fitted to place” by governments seeking to find workable solutions to preserving the natural world and providing for human needs.

Nature Needs Half is now being implemented across all jurisdictional scales, and in surprising and sometimes novel ways, in cities and countries around the world. The core concept of protecting half of an area for nature is being “fitted to place” by governments seeking to find workable solutions to preserving the natural world and providing for human needs.

CRD Regional Parks, through its 2012-2021 Strategic Plan, has advanced the idea of Nature Needs Half as a foundational principal for regional sustainability. CRD Regional Planning is currently developing a Regional Sustainability Strategy (RSS), and the concept of Nature Needs Half is included as a key goal under the draft Natural Environment Strategic Policy Direction. As the RSS process unfolds throughout 2014-2015, there will be ample opportunities for regional dialogue around the values, benefits, and challenges of adopting Nature Needs Half as a core principle of regional sustainability.

What is Nature Needs Half?

Nature Needs Half is a simple concept to understand—put most succinctly, it means saving half of the world’s lands and waters for the protection of nature. Nature Needs Half was developed by the WILD Foundation of Boulder, Colorado [2]. The WILD Foundation is a progressive leader in global wilderness conservation, perhaps best known for successfully organizing the long-running World Wilderness Congress, the world’s most preeminent public conservation project and environmental forum.

Nature Needs Half is a simple concept to understand—put most succinctly, it means saving half of the world’s lands and waters for the protection of nature. Nature Needs Half was developed by the WILD Foundation of Boulder, Colorado [2]. The WILD Foundation is a progressive leader in global wilderness conservation, perhaps best known for successfully organizing the long-running World Wilderness Congress, the world’s most preeminent public conservation project and environmental forum.

The WILD Foundation also recently launched the WILD Cities Project, which it describes as “a new concept of urbanism where wild nature is highly valued and its conservation is a conscious part of human life in cities worldwide” [3]. Goals of the WILD Cities Project include identifying successful urban initiatives aligned with the principles of Nature Needs Half, formulating criteria for defining a WILD city, and developing strategies to communicate to the public the need for nature in our cities.

A notable early proponent of a Nature Needs Half approach is the famed Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson, who in his book The Future of Life (2002) proclaimed “half the world for humanity, half for the rest of life, to make a planet both self-sustaining and pleasant” [4]. This statement emanates from the many years of research by conservation biologists who have been examining the question of how much land is needed to ensure the maintenance of biodiversity.

Although the prevailing belief has long centered on a 12% conservation target, many recent studies have shown that this target is too low to maintain diversity. Many scientists now believe that the minimum amount of protected area necessary for a given area of land is generally between 25% and 75%. Given this variability, most have settled on 50% as a workable percentage that can provide a viable balance between ecosystem services and economic development. This new understanding is pushing governments around the world to adopt new policies that will protect at least half of their land base for nature.

One of the key concepts underlying a Nature Needs Half approach is that of connectivity. Landscape connectivity is necessary to maintain the full range of life-supporting, ecological and evolutionary processes, the long term survival of species, and an area’s resilience in the face of environmental change [5]. Many conservation planning efforts have been initiated to determine how much and which lands should be targeted for conservation. A general consensus is that it depends on the characteristics of the area under consideration—its physical characteristics, its suite of species to be conserved, its past-land use decisions, and other factors. The overall goal, however, is to create enough connectivity that species can move in response to stressors including climate change, invasive species, and habitat fragmentation, degradation, and loss.

This approach to Nature Needs Half will work well in the Capital Regional District (CRD). The CRD contains a rich assemblage of ecosystems and species within its 245,000 hectares on Southern Vancouver Island. Fortunately, a significant portion of the CRD is still in a semi-wilderness condition (much of which is formally protected as parks), while considerable forestry, agricultural, rural and suburban open space networks exist, all of which can serve as the core of a connectivity matrix.

Why is the CRD considering Nature Needs Half?

The CRD is ideally positioned to consider a Nature Needs Half approach as a foundational principal for regional sustainability. The region is blessed with abundant natural landscapes and a complex geography and climate that support a diverse range of ecosystems, a number of which are globally rare or endangered. Fortunately, the region has already set aside significant areas for nature protection and it still contains an abundance of forestry lands, agricultural lands, and other types of open space that could contribute to a Nature Needs Half vision. The region is equally fortunate to have an effective governance structure, progressive municipalities and electoral areas, and a public that widely supports the goal of regional sustainability and effective stewardship of natural resources.

In spite of such strong support, the CRD is still faced with intense development pressures and associated negative impacts on the health of the region’s biodiversity and overall resiliency to environmental change. This fact underscores the critical importance of on-going, appropriate stewardship of the region’s lands and waters, and the need to develop a far-sighted approach to balancing the needs of “nature” (which also encompasses human needs) with that of economic growth and development.

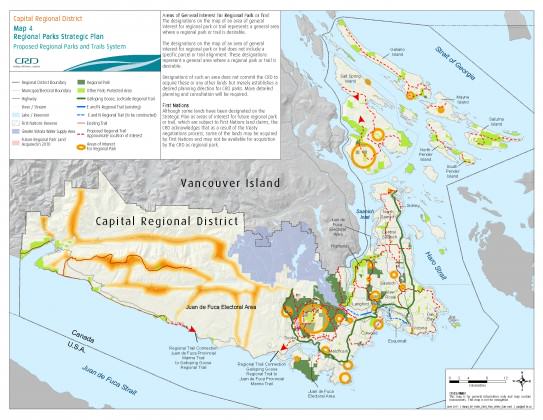

There are a number of ways the CRD has already started to address this problem. CRD Regional Parks recently completed its Regional Parks Strategic Plan 2012-2021 [8]. A core concept of the strategic plan is Nature Needs Half. Regional Parks, through its strategic plan, recommended that Nature Needs Half be brought forward for discussion in preparing the Regional Sustainability Strategy (RSS).

CRD Regional Planning is leading the development of the RSS during 2014-2015 [9]. A key component of the RSS process is extensive public consultation designed to ensure a wide range of perspectives are considered during the strategy’s preparation and approval stages. The RSS will provide the framework for long-term regional sustainability by seeking to preserve and revitalize natural systems, foster social resilience and community well-being, and generate ongoing prosperity and affordability. Regional Planning supports Nature Needs Half as an important cross-cutting theme that can inform each of its key strategic areas.

There is clearly more work that needs to be done to understand what Nature Needs Half might mean if applied within the CRD. Although a significant focus of Nature Needs Half is on large landscape conservation, the CRD can also “fit it to place” by including urban, suburban, and rural elements that will directly benefit regional residents right where they live, thereby maximizing the value of such an approach. To this end, it is important to understand and define what “nature” and “half” might mean in a regional context.

What might constitute “Nature” within the CRD?

Within the CRD, it is entirely sensible to consider the full range of the region’s natural systems, functions, and elements in a Nature Needs Half approach. For instance, we would want to include those wilderness areas that still exist for their value as wildlife corridors, carbon sinks, and biodiversity strongholds (among other values), but we would also want to think about other types of landscapes that have similar or different values. In this sense, we need to think about landscapes modified by human use that still retain their relevance and value as “nature.” These landscapes will necessarily include working forests, agricultural lands, public and private open space, non-wilderness parks and protected areas, greenways, riparian zones, watersheds, wetlands, lakes, rivers, ponds, and the nearby marine environment, among others.

If such a Nature Needs Half approach is to be successful, it is necessary to examine the other part of the equation—that of “half.” What does it mean to protect “half” of the region for nature.

What might constitute “Half” within the CRD?

When thinking of what protecting “half” of the CRD for nature means, it is necessary to look at it from the perspective of governance, equity, and scale. From a governance perspective we recognize that our system is complex, with multiple layers of government involvement in the structuring and management of our daily affairs. One definition of governance that applies to the management of nature is from the IUCN Natural Resource Governance Working Group [11]:

Understood in this way, governance, including how it shapes and is shaped by the political economy of local, provincial, and national decision-making, is a critical determinant of the effectiveness and equity outcomes of biodiversity conservation, and of the contribution that abundant nature makes to people’s well-being, empowerment and sustainable development.

Understood in this way, governance, including how it shapes and is shaped by the political economy of local, provincial, and national decision-making, is a critical determinant of the effectiveness and equity outcomes of biodiversity conservation, and of the contribution that abundant nature makes to people’s well-being, empowerment and sustainable development.

When we think of protecting half of the region for nature from a governance perspective, we must acknowledge there are many stakeholders, including the federal and provincial governments, the regional district, municipalities and electoral areas, First Nations, and civil society. Each of these stakeholders is bound to the other by complex sets of rules and traditions that determine how power is exercised and how decision-makers are held accountable for their decisions.

Within this governance framework, we have a collective responsibility to steward our natural resources wisely. Many opportunities exist for collaborating on a comprehensive nature protection strategy involving all levels of government and in partnership with civil society.

In this sense, the question of equity arises. It would be impossible to mandate to the federal or provincial governments, the regional district, First Nations, municipalities, electoral areas, businesses, or private citizens that they must protect half of their land for nature. How would this be done, and who would be responsible for it? What would be the impact on different stakeholders? How feasible would it be given current development patterns? How would private property rights be addressed?

One obvious tactic is to embed Nature Needs Half within the RSS, which is a regionally representative approach to achieving equitable sustainability outcomes. The RSS, which will be eventually adopted by each municipality and electoral area in the region and approved by the Province, will feature a set of strategic priorities that should lead the region to greater sustainability. In this sense, all share in the costs and benefits of achieving regional sustainability, and each stakeholder commits to making it work for the benefit of all.

Nature Needs Half within this scenario is achievable through the individual and combined efforts of RSS signatories. If this is true, then the scale at which it is achieved must be addressed. Scale in this context refers to what and where the “half” will come from. There are many possibilities. If a goal is to create a seamless nature connectivity matrix stretching from our core urban areas to the most remote and wild corners of the region, then we must consider all of our natural areas and features as potential contributors to the “half.”

How each level of government and civil society will contribute to the actualization of Nature Needs Half needs to be discussed during the development of the RSS, as well as afterwards if it is adopted as a core principle of regional sustainability. A fundamental tenet, however, is that each level of government, First Nations, businesses, civil society organizations, and private individuals each have a role to play in supporting the designation of lands or features for nature protection and a shared responsibility for achieving Nature Needs Half.

Contributing to regional sustainability

One of the most important reasons to adopt a Nature Needs Half approach within the CRD is for its contribution to environmental sustainability. In particular, protecting nature means protecting the full suite of “nature’s services” or “ecosystem services.” These ecosystem services underpin our human economies and livelihoods.

Despite their critical importance, the capacity of ecosystems to provide essential services is being degraded at an alarming rate. In 2005, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), a four-year study of the state of the world’s ecosystems involving more than 1,300 experts from 95 countries, reported that over 60 percent of the earth’s ecosystem services were already degraded. This negative trend, they concluded, was set to continue at an accelerating pace over the next half century [12].

Climate change is exacerbating the degradation of ecosystems and the loss of ecosystem services [13]. Decisions concerning land acquisition and conservation strategies need to consider the potential impacts of climate change, and incorporate linkages and corridors to other natural areas for species migration. This approach suits a Nature Needs Half approach, which necessarily includes protection of priority areas and elements in an overall connectivity matrix [14].

The quote below highlights the value of protecting nature as a climate change strategy [15]:

Another important aspect of nature’s services is its “natural capital” benefit—or human valuing of nature’s economic contributions. Traditionally, natural capital services weren’t accounted for in the market economy, and so were often under-valued or treated as non-existent. However, this approach to natural capital is changing, as it is becoming clear that the services nature provides are extremely valuable in monetary terms” [16].

Another important aspect of nature’s services is its “natural capital” benefit—or human valuing of nature’s economic contributions. Traditionally, natural capital services weren’t accounted for in the market economy, and so were often under-valued or treated as non-existent. However, this approach to natural capital is changing, as it is becoming clear that the services nature provides are extremely valuable in monetary terms” [16].

According to the David Suzuki Foundation, the establishment of greenbelts of protected forests, agricultural lands, wetlands, and other green spaces around cities like Toronto and Ottawa has helped to protect essential ecosystem services like water filtration and wildlife habitat [17]. The benefits provided by southern Ontario’s Greenbelt alone have been conservatively estimated at $2.6 billion annually.

According to the David Suzuki Foundation, the establishment of greenbelts of protected forests, agricultural lands, wetlands, and other green spaces around cities like Toronto and Ottawa has helped to protect essential ecosystem services like water filtration and wildlife habitat [17]. The benefits provided by southern Ontario’s Greenbelt alone have been conservatively estimated at $2.6 billion annually.

The David Suzuki Foundation recently completed a landmark natural capital valuation study for the purpose of determining the non-market benefits provided by the natural capital within B.C.’s Lower Mainland (e.g. greater Vancouver metropolitan area) and its watersheds [18]. The report found that the top three benefit values provided by the study area’s ecosystem services were:

- Climate regulation resulting from carbon storage by forests, wetlands, grasslands, shrub-lands and agricultural soils;

- Water supply due to water filtration services by forests; and

- Flood protection and water regulation provided by forest land cover.

The total value for all natural capital benefits provided by the study area was estimated to be $5.4 billion per year, or about $3,880 per hectare. This translated to an estimated value of $2,462 per person, or $6,402 per household each year [19].

Supportive measures for a Nature Needs Half approach

A key consideration for governments and citizens is to understand what measures already exist to facilitate the protection and expansion of a green infrastructure network [22]. Fortunately, much work has been completed in this regard. For instance, the Green Bylaws Toolkit for Conserving Sensitive Ecosystems and Green Infrastructure advances policy goals, objectives, and criteria for protecting green infrastructure that resonates with a Nature Needs Half approach [23].

The Toolkit advances three broad goals:

- Protect and maintain the integrity of sensitive ecosystems;

- Restore ecosystems when opportunities allow; and

- Ensure that green infrastructure plays a role in promoting fiscally responsible local government services and programs.

To achieve these goals, the Toolkit recommends pursuing seven objectives:

- Contain urban development within a compact area;

- Maintain environmentally sensitive lands outside urban containment boundaries as large lot parcels (20+ hectares), parks, or protected areas that are connected by greenways;

- Prevent degradation and fragmentation of sensitive ecosystems and encourage connections among ecosystems;

- Prevent development of subdivisions and individual lots on or near sensitive ecosystems;

- Maintain the integrity of the ecological systems of which sensitive ecosystems are a part;

- Restore degraded ecosystems;

- Ensure adequate assessment of the impacts of development and carry out mitigation measures.

The Toolkit then lists two criteria that affect the ability of local governments to implement these objectives:

—Simplicity of administrative systems; and

—Good definition of the costs and benefits of ecosystem protection.

The Toolkit identifies a number of measures available to local governments for protection of green infrastructure [24]. Generally, these measures fall into five categories: land use instruments, fiscal incentives, liability limitations, market incentives, and increased education/capacity building [25]. Together these measures provide a suite of strategies that can be utilized on behalf of nature conservation.

Of course, there are many more exciting and innovative urban nature conservation strategies being implemented across North America and around the world. Many of these have been written about in other Nature of Cities blogs, such as the Biophilic Cities Initiative, the Metropolitan Greenspaces Alliance, and the Green Seattle Partnership. All of these approaches are contributing to a growing network of global cities that are “fitting to place” accessible, healthy, and abundant nature in the midst of densely populated urban spaces.

Summary

Most of the world’s leading scientists and governments recognize that the escalating global ecological crisis demonstrates the insufficiency of our current conservation efforts and that we need to do more to stop this alarming trend. Fortunately, we possess good knowledge about the environment, especially about how much land and water we must protect to maintain the full range of biodiversity and protect human health. Research over the last 20 years or so indicates that we must set aside at least half of a given region for protection and we must work hard to interconnect core areas with other such areas to provide resiliency in the face of unprecedented environmental change [26].

Currently, approximately 19% of the CRD is protected as parks or restricted watershed, for a total of 47,826 hectares. While this percentage exceeds the current global protected areas standard (e.g. 12%), it falls far short of the 50% that conservation scientists believe is necessary to cope with emerging environmental and human health challenges. Fortunately, the CRD has adequate lands to protect half of our region for nature. Within the CRD can be found urban green features, local to federal park and trail systems, open space, resource lands, and wilderness. The CRD can create a sustainable future based on a Nature Needs Half approach given enough public and political will.

Although the CRD is committed to achieving regional sustainability, more work needs to be done to understand how to define and operationalize a Nature Needs Half approach for the region. Next steps in this regard could include:

—Ensuring that Nature Needs Half remains in the Regional Sustainability Strategy and is included in public dialogues about the region’s future;

—Holding focus sessions or other community engagement events where the topic of Nature Needs Half can be explored in more detail and the results analyzed and disseminated back out to politicians and the public;

—Interviewing others involved with a Nature Needs Half (or similar approach) to determine strategies, opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned, with applicability to the CRD.

—Developing a set of Nature Needs Half strategic priorities, with associated goals, targets, indicators, and milestones.

—Preparing a Nature Needs Half action plan and green infrastructure strategy.

The case is clear that infusing and protecting nature in and around our cities provides innumerable benefits for human health and well-being, as well as providing a lifeline for species and ecosystems that depend on our positive actions in this regard. We owe it to ourselves and to the incredible diversity of life on earth to act now to protect at least half the worlds’ lands and waters for nature. The CRD, in its own small way, can partially answer this larger call to action by adopting a Nature Needs Half approach for regional sustainability.

Lynn Wilson

Victoria, British Columbia

End Notes

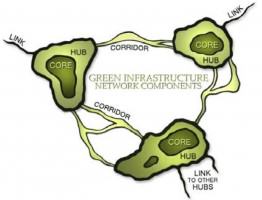

[1] Capital Regional District (CRD) is the regional government for 13 municipalities and three electoral areas on Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. See the CRD website at: https://www.crd.bc.ca/about/what-is-crd. [2] See The WILD Foundation at http://www.wild.org/. [3] WILD Foundation, WILD Cities Project at: http://www.wild.org/main/world-wilderness-congress/wild10/. [4] Wilson, E. O. (2003). The future of life. New York: Vintage Books. [5] The Wild Foundation (2009). Nature Needs Half information sheet. Accessed on 3/14/13 at http://natureneedshalf.org/why-nature-needs-half/. [6] Conceptual Green Infrastructure Network from the document: “Refinement of the Chicago Wilderness Green Infrastructure Vision, Final Report June 2012”, accessed at:http://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/11696/GIV20_FinalReport_2012-06.pdf/dd437709-214c-45d6-a036-5d77244dcedb. The report defines the connectivity network as: “The building blocks of the network are “core areas” that contain well-functioning natural ecosystems that provide high quality habitat for native plants and animals. By contrast, “hubs” are aggregations of core areas as well as nearby lands that contribute significantly to ecosystem services like clean water, flood control, carbon sequestration, and recreation opportunities. Finally, “corridors” are relatively linear features linking cores and hubs together, providing essential connectivity for animal, plant, and human movement.” [7] From CRD Regional Parks Strategic Plan 2012-2021 at: Regional Parks Strategic Plan at https://www.crd.bc.ca/docs/default-source/parks-pdf/regional-parks-strategic-plan-2012-21.pdf?sfvrsn=0. [8] Regional Parks Strategic Plan 2012-2021, p. 16-17. See: http://www.crd.bc.ca/parks/planning/strategicplan.htm. [9] See CRD Regional Growth Strategy at: CRD Regional Planning – Regional Sustainability Strategy at: https://www.crd.bc.ca/plan/planning-other-initiatives/regional-growth-strategy. [10] Excerpted from “Refinement of the Chicago Wilderness Green Infrastructure Vision, Final Report June 2012”, (p. 7-8) at:

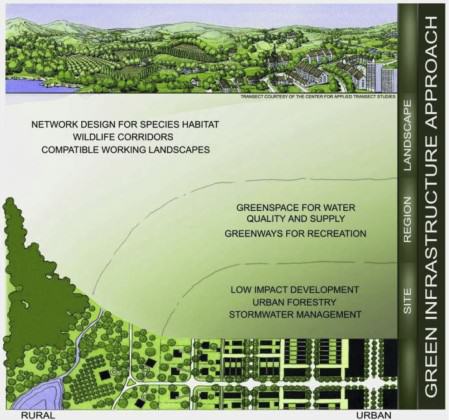

http://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/11696/GIV20_FinalReport_2012-06.pdf/dd437709-214c-45d6-a036-5d77244dcedb. Green infrastructure is defined in the report as: “The regional green infrastructure network provides multiple benefits. At its broadest, landscape‐ scale green infrastructure provides important ecosystem services like clean air and water, critical plant and animal species habitat, and wildlife migration corridors along with compatible working landscapes. At the regional scale, green space can help protect water quality and help ensure the availability of drinking water. Green infrastructure can also provide key recreational areas that link people to natural lands and facilitate the use of transportation modes other than automobiles to reach key community assets. At the site scale, green infrastructure enhances neighborhoods and downtowns through environmentally‐sensitive site design techniques, urban forestry, and storm-water management systems that reduce the environmental impact of urban settlements. All of these scales of activity can be linked together and can ensure sustainability in urban, suburban, and rural areas of a region.” [11] IUCN (2013). Draft Concept (v. 10) for discussion: Building an IUCN Natural Resources Governance Framework. [12] Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current state and trends, Volume 1. R. Hassan, R. Scholes, and N. Ash (eds.), Washington DC: Island Press. [13] Wilson, S. J. and Richard J. Hebda (2008). Mitigating and adapting to climate change through the conservation of nature. The Land Trust Alliance of British Columbia. [14] Ibid. p. v. [15] Ibid. p. viii. [16] David Suzuki Foundation, Sara Wilson (2010). Natural capital in BC’s Lower Mainland: Valuing the benefits from nature. Prepared for the Pacific Parklands Foundation. Accessed at: http://www.davidsuzuki.org/publications/reports/2010/natural-capital-in-bcs-lower-mainland/. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid. [19] Ibid. p. 8-10. Data based on 2006 census data of 2.2 million people within the study area with an average of 2.6 people per household. [20] See the Go To 2040 Plan at: http://www.cmap.illinois.gov/about/2040/livable-communities/open-space. [21] World Resources Institute (2011). Forests and water: Green infrastructure can be less expensive than gray infrastructure. Accessed at: http://www.wri.org/stories/2011/02/protecting-forests-protect-water-us-south. [22] “Measures” here refers to the range of incentives, markets, and practices that exist to protect green infrastructure. [23] Green Bylaws Toolkit for Conserving Sensitive Ecosystems and Green Infrastructure. Available at: www.greenbylaws.ca. [24] Ibid. pgs. 37-137. [25] L. Yonavjak, C. Handon, J. Talberth, and T. Gartner (2011). Keeping forest as forest: Incentives for the U.S. South. Prepared for the World Resources Institute. Accessed at: www.wri.org/publications. [26] Nature Needs Half at http://natureneedshalf.org/home/.

Leave a Reply