On 16 March 2014, China’s State Council released the “National New-type Urbanization Plan,” a long-awaited top-down effort to utilize urbanization as an engine for economic growth in the near future. The plan details an ambitious series of goals the government seeks to accomplish by 2020. However, speeding up the urbanization process will have far-reaching environmental and social effects for China.

Background of the plan

The Chinese leadership has attached great importance to the Urbanization Plan. It took 3 years to complete the plan and involved intensive collaboration across agencies. The effort was spearheaded by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) joined by the other 12 major government ministries.

The Urbanization Plan is strategically focused on the macro-level and aims to direct national-level policy. It is on the highest level of national plans much like the “Twelfth Five Year Plan.” Therefore, the Urbanization Plan can be seen as a coordinated, top-level effort to increase the population of China’s cities while addressing critical quality of life issues for urban residents.

Content

Overall, the plan stresses what Premier Li Keqiang has referred to as “human-centered urbanization.” Fundamentally, this concept involves increasing the urbanization rate from the current level of 53.7% to 60% by 2020. Under China’s current internal household registration or hukou system, rural-urban migrants often lose out on social benefits once they leave their homes in the countryside. In order to assure better integration of new residents into urban life, the government has pledged to guarantee better access to schools and hospitals for 100 million migrants. In total, the plan calls for 45% of all the new urban residents who have moved into cities to receive urban hukous, a process that will place an immense strain on municipal resources. The question of integrating the remaining 55% of new residents with urban hukou remains an unresolved dilemma, as China cannot achieve full urbanization while the majority of the population moving into cities have no path towards receiving full social benefits.

Despite the Urbanization Plan’s ambitious targets, there is no clear mention of how local governments can raise the funds to accommodate the necessary upgrades to the provision of social benefits such as healthcare and education. In addition, a wave of migration to cities will put an immense strain on urban transportation and waste management infrastructure. In order to reach these goals and avoid a rehash of the wasteful government spending on prestige projects during the post-recession stimulus, China will need to rethink changes to taxation, land use, and urban planning policy that will be integral to achieving financially and environmentally sustainable urbanization.

Tax reforms

The central government needs to implement incremental tax reforms that give localities the ability to raise taxes for improvements in infrastructure. While there have been pilot property tax programs in Shanghai and Chongqing (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: China’s Property Tax Reform: Progress and Challenges)[1], the government has no plans to expand these pilots. As most of the responsibility for providing social services lies with the municipal government, improving access to these benefits without sufficient investment is impossible. Local governments finance 80% of spending on health and education (World Bank: Financing Cities: Fiscal Responsibility and Urban Infrastructure in Brazil, China, India, Poland and South Africa)[2], if cities are to accommodate a wave of new residents, fiscal reform needs to happen.

Implementing China’s new urbanization plan will present an enormous cost for China’s municipalities to bear. To achieve a more environmentally and sustainable form of urbanization, local governments need to cease unnecessary land seizures and take the initial steps towards putting a property tax in place. China’s cities have seen a surge in capital investments and new construction, however without a property tax much of the added value to all the construction is completely lost to the municipal government. Currently, Chinese property owners enjoy the benefits of public goods without bearing any of the fiscal responsibility. For example, a development located next to a newly completed subway line gains value, however the developer did not contribute anything to the public construction of the subway. This can be amended with a gradually phased in property tax. Such a tax would optimize land use and realign local government revenues with their expenditures. It would also create an incentive for the development of vacant or underutilized urban land.

New development should meet the critical needs that urban migrants will have upon arrival to the city. While the narrative of an oversupply in China’s housing market has gained traction in the Western media, however much of the new construction consists of costly high-rises on the periphery of urban areas. Despite the construction boom, Chinese cities have a fundamental lack of affordable housing. In order to be fully integrated in the urban fabric, new residents must be able to afford to live within the city in mixed-income neighborhoods rather than being ostracized in remote bedroom communities. The development of underutilized urban land within the city itself needs to make space for affordable housing. The government has signaled that it will spend more than $162 billion USD to redeveloping urban “shantytowns”, however there is no comprehensive plan in place to accommodate displaced residents badly in need of affordable housing. To help alleviate the housing needs of residents, municipal governments should allocate underutilized industrial land suitable for habitation for affordable housing. They could also increase affordable housing supply by adopting an “inclusionary housing” program modeled after New York City. Inclusionary housing incentivizes developers to designate a portion of the property as affordable housing in return for bonuses such as increased floor area.

As key beneficiaries of municipal services, property owners should contribute to urban development by paying taxes. Therefore, local governments could benefit from increased land values, giving them direct incentives towards intensive-land use instead of wasteful, sprawling developments without residents. This would also resolve the cash flow problems of local governments so they would have more capital to invest in the urban infrastructure necessary to acheive the targeted urbanization rate.

Land use

Under the current land use system, all rural land belongs to collectives. Farmers, as prospective urban residents, have very little land rights and cannot decide whether to buy or sell land without government approval. Without the ability to leverage their land as a source of income China’s rural population is at a critical disadvantage and will only fall behind urbanites if they choose to migrate to cities.

In order for this level of urbanization to occur, land ownership rights for rural land need to specified. Title registration needs to be improved upon and there must be a unified system of sales, contracts and procedures in order to define collective ownership and clarify ownership rights. This will protect citizen’s land from eminent domain seizures that develop rural land into private developments. Eminent domain needs to be restricted to land developed in the public interest, as opposed to merely enriching local government interests.

In the past few years, land requisition has been driven by administrative decisions as opposed to market demand. This has led to an urban growth pattern that is characterized by unnecessary sprawl. As a result, the average population density in Chinese cities has dropped by 25% in the last decade (World Bank: Urban China: Towards Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization)[3]. Due to the funding gap between the central government and the localities, municipal governments have excessively relied upon and sales to provide services. By reclassifying rural land belonging to the collective as urban property, local officials are then able to cheaply convert this land and sell it at a higher price to property developers. This pattern of urban sprawl is completely out of sync with local market demand for new construction. About 90% of prior demand for urban construction was met through rural land expropriation. Meanwhile, the existing stock of urban construction land sits by vacant and unused. Construction needs to follow the demand for new housing stock, and new development should take place on property already designated as urban land so as not to create excess housing far removed from the actual city limits.

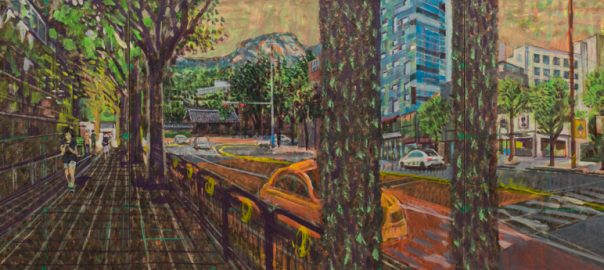

In comparison with other countries in Asia, China still uses a significant portion of its urban land for industrial purposes. Low-density industrial land is by no means the best use of scarce urban land resources, and it takes up critical space that could be utilized by the services sector. According to the World Bank’s comprehensive report on China’s urbanization plan released this March, Seoul uses only 7% of its urban land for industrial parks while Hong Kong uses only 5%. If the current pattern of low-density sprawling growth continues, China will need an additional 34,000 km2 of land to accommodate new urban growth in the next decade (World Bank: Urban China: Towards Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization). This is a problematic trend that must be addressed in order to reverse sprawl and transition to more productive and less pollution-intensive uses of urban space.

Urban planning

Urban planning has the ability to strengthen innovation and governance in society. Due to the fact that the pattern of China’s economic growth is changing, formerly manufacturing based economic growth is transitioning to a more service and technology industry led mode of development. In order to meet the growing needs of Chinese society, cities need to improve the function of public urban spaces.

The new urbanization plan also specifically mentions the need to strengthen the management and control of urban planning, accelerate the construction of green cities, and the implementation of air pollution control action plans to improve air quality. We believe that rational urban planning can indeed play a role in improving urban air quality. Since the transportation sector contributes to air pollution in cities, reducing car-dependence in favor of walking and public transit can alleviate the problem. Rational urban planning can reduce emissions generated in urban areas. Key principles of sustainable urban planning include reducing the size of city blocks, more road network density, mixed-land use, transit-oriented design, and reduced energy use. All of these factors have the potential to significantly impact urban sources of pollution.

These principles need to be put into action by city planners as soon as possible in order to stop the spread of air pollution in cities and counter the harmful effects it has on the health of residents. The physical layout of cities should also take into account how it contributes to the dispersion of air pollution: industrial zones should be located downwind of the city center; the main highway networks in a city should also be favorably located with regards to the urban dispersion of vehicle emissions. Green belts should also be utilized to limit undue urban sprawl and provide relief from vehicle exhaust. In high density urban areas along with the city’s main transport node, controlled ventilation systems have been proven to be effective in improving ambient air quality along those corridors. The construction of one such system has just started in Beijing.

Environmental impact

From an environmental perspective, the Urbanization Plan will result in a construction boom to build the approximate 30 million units of housing over the next 7 years.The effort to reach the 60% urbanization rate target detailed in the Plan will depend heavily on the construction industry. This will require an uptick in consumption of the three things China cannot afford to waste: water, energy, and land. Any new developments cannot proceed without exacting a significant toll on the environment as coal, cement, and steel manufacturing are all heavily polluting industries tightly linked to new construction. Further complicating the issue, some of these new development projects have received the designation of “eco-cities”. Unfortunately, attaching the “green” label to new developments is more often than not a useful marketing scheme. Wide streets, inefficient use of building materials, and car-dependent design ensure that these developments are “eco” in name only. Additionally, the practice of using land grabs to finance municipal expenses has created a pattern of sprawl found throughout the Chinese urban landscape. Without tax reform or changes to rural resident’s property rights Chinese cities will grow in a low-density, car-dependent manner that will only put a greater strain on the nation’s fragile environment. Furthermore, the government must adhere to strict international green building standards to ensure that all new construction meets benchmarks for sustainability. A large part of this process should involve retrofitting existing buildings to be more energy efficient. These retrofits are much more cost-effective and low-carbon when focused on existing developments near established urban cores.

Lastly, such top down urbanization measures cannot proceed in a sustainable manner without a shift in consumption. The leadership sees urbanization as a way to maintain growth and counter an economic slowdown by boosting the number of consumers, as urban residents have been shown to purchase significantly more goods and services than their counterparts in the countryside. Despite the economic benefits, a rise in the urban consuming class could exacerbate China’s environmental problems. According to a World Bank study, China’s urban residents use three times as much energy as rural residents (World Bank: China Urbanizes: Consequences, Strategies, and Policies)[4]. An exponential increase in energy demand without a paradigm shift towards more sustainable consumption would only lead to more congestion, air pollution, and associated threats to public health. All of this would occur while a significant portion of the urban populace is effectively disqualified from receiving health benefits. Given that its urban areas already suffer from air pollution, congestion, and a dearth of green space, can China really achieve the economic benefits of urbanization without exacerbating the severity of its environmental damage? These factors could potentially compound existing quality of life issues in Chinese cities. If China does not seriously consider reforms to fiscal, environmental, and land use policy it will soon see diminishing returns to urbanization.

Jack Maher and Xie Pengfei

Beijing

Notes:

[1] Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, China’s Property Tax Reform: Progress and Challenges (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA April 2012). [2] World Bank, Financing Cities: Fiscal Responsibility and Urban Infrastructure in Brazil, China, India, Poland and South Africa (World Bank: Washington, DC April 2017). [3] World Bank, Urban China: Towards Efficient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Urbanization (World Bank: Washington, DC March 2014). [4] World Bank, China Urbanizes: Consequences, Strategies, and Policies (World Bank: Washington, DC January 2008).about the writer

Pengfei XIE

Pengfei is China Program Director of RAP (Regulatory Assistance Project). RAP is a US based non government organization dedicated to accelerating the transition to a clean, reliable and efficient energy future.

As stated by Jack Maher regarding urbanisation and imapct in China is also the case with other countries especially in Third World countries. People oriened urbanisation is warrented but never implemented. Goals are not effectuated. Where is the question of sustainability? We have to delve towards viable urbanisation for social amelioration.