From my office, on the 9th floor of a tall building in an academic campus in Bangalore, I have a birds-eye view of the city’s peri-urban surroundings. To the west, I can see a 6-lane high-speed highway choked by traffic, full of people frenetically commuting from their homes in city to their jobs in the globally famous Information Technology campuses located just outside. To the east, I am fortunate to witness a completely different picture. A tranquil marshy wetland and freshwater lake, with dozens of cows grazing and cooling down in the water while the mid-day sun blazes overhead, accompanied as companions by hundreds of cattle egrets feeding on the insects that annoy the cattle. This idyllic picture of cooperation, mutualism, and rural bliss has evolved and been sustained over centuries in Bangalore. (Bangalore’s lakes are not natural, but were created and maintained by local communities, with a history that can be traced as far back as 450 AD.) Yet even this picture is marred by construction and dumping of large mounds of debris onto the wetlands at one side of the lake.

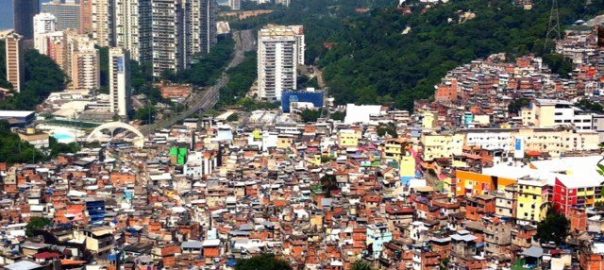

Such contradictions of livelihoods and lifestyles, urbanity and rurality, shared cooperation and rampant self-interest, may be typical of many Indian cities but are certainly not unique to India. Certainly, the situation I have just described in Bangalore could be familiar to people in many other countries, even continents. Conflicts such as these just described have given rise to, and are exacerbated by, some of the worst inequities that the world has ever experienced. A recent Oxfam report, released on the occasion of the World Economic Forum meeting at Davos, quotes a staggering figure: the world’s richest 85 people now collectively own as much money as the world’s poorest 3.5 billion! In a world that seems to be moving towards increasing self interest, and growing private control of the environment and natural resources, how can we ever hope or plan for a better future?

Following the example of Elinor Ostrom, who received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics for her pioneering work on the commons, we need to enlarge our discussion of models of urban governance to include a third alternative to the commonly espoused twin pillars of private and government administration, i.e., that of the community. Research from case studies in diverse contexts across the world has now proven clearly that multi-level collaborations between local community groups, civic society actors and government administration are essential for the effective, equitable and sustainable governance of natural resources. For such collaborations to be effective, they should however enable the scope for negotiations on an equal slate between different groups, such as high income apartment owners and slum residents, that are likely to have very different power structures. Developing the platform to allow negotiations at an equal level is particularly challenging in cities given the underlying context of high economic growth, which puts natural resources at stake. The imbalance between power structures becomes every more stark when natural resources are monetized, whether in the context of fracking and industrialization in China and the USA, or ground water withdrawal and water privatization in Latin American and Indian cities.

Effective governance is the key, obviously. Yet, to address these thorny challenges requires an adequate appreciation of the complexities of politics and political science, which is often lacking in approaches adopted by governments, influential thinktanks and international policy makers. Clearly, in today’s information age, lack of information does not constitute a barrier. More likely, it is the lack of dialogue, exacerbated by the imbalance in power, that creates barriers to cooperative governance for inclusive cities. It is the same lack of dialogue and imbalance in power between the urbanized landscape to the west of my office (with its character shaped by the shared use of large roads by high speed traffic), and the rural landscape to the east (with its character shaped by the shared use of wetlands by cattle and people), that leads to the dominance of the road over the lake, of the need for speed and linear growth over reflection and an appreciation of the cycles of life. Such an imbalance in appreciation, in ideology, almost inevitably leads to the disappearance and decay of these commons in urban areas. Cities thus become oceans of gray in a quest for endless economic growth, swallowing up all the little islands where commoners once thrived and flourished in respectful contestation and adaptive dialogue with nature.

Our studies, as well as practical experience with community governance in the context of Bangalore’s lakes, has strongly highlighted the role for dialogue between communities and city government in providing the conditions that are inductive for effective co-management. This is particularly important in high growth urban contexts, which face political economic challenges of rent seeking, corruption and economic profit-making that can bias planning towards short term profit seeking, at the expense of long term sustainability. Fortunately, Bangalore seems to doing well in this regard, with a number of lake communities coming forward to reclaim derelict lakes in their neighborhood, supported by civic action in the form of Public Interest Litigations and an active judiciary that places pressure on city administration.

Such initiatives cannot be taken for granted, however, and are few and far between at the national level in India and indeed, in most countries with fast growing cities. Our only hope for scaling up such action is to enable outreach at a mass scale, through interdisciplinary education that crosses boundaries, engages with students, local communities, policy makers and private actors, and facilitates respectful contestation across groups of actors joined in the common goal of seeking equitable pathways towards greater urban sustainability. Engaging with problems of sustainability in an equitable, fair and just manner will require the fresh perspectives engendered by such discussion.

Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

Note: This blog post draws substantively on the article ‘Reflections’ by Harini Nagendra in The Commons Digest: Publication of the International Association for the Study of Commons, Spring 2014: Number 15, pp. 15-18.

This tension is evident the world over – between environment & social groups and the push for “development”.

The “solutions” generally come down through “consultation” & “democracy”, but this just means that minorities get overwhelmed. The processes used are actually designed to ensure that “progress” as defined by business interests is achieved and, if the poor are considered at all, the bottom line is that the benefits of progress will trickle down to them.

No one can pretend that the current urban slum model is viable, but the usual process of public meetings

are of their nature confrontational and are designed to control inputs and outcomes – not a good forum for genuine progress.

Meetings are notorious processes where dominant voices get the floor & quieter ones are silenced – in fact quiter people don’t attend meetings because they know the process is stacked against them, so meetings are often worse than useless.

With the very best of preparations, where there has been gentle & patient discussion over many weeks/ months/ years, it comes down to a “representative” having to put the bottom line, so even with the best “representatives” in attendance, it comes down to a very brutal situation where might is right.

I believe entirely new processes are needed for the poor to be heard, & for them to find empowering ways to collaborate on things they deem important.

I’ve been developing a very different process using the internet which could work here, so if anyone wants info about it, please contact me

Regards

Chris Baulman

@landrights4all (Twitter)