If Thoreau were alive today, he might move to Brooklyn, not the woods. Cities of the early 21st century are where life can be lived most intensely, the place for sucking, routing, shaving, and driving life into the corner, as Thoreau famously described the purpose of his retreat to Walden Pond. Cities are where innovations happen, and he needed new ideas. He thrived on them. At 28, instead of cabin on the edge of town, Henry David could find the marrow of life while renting a walk-up in Greenpoint or Gowanus and exploring the ecosystems of the city. He certainly had the beard for a Brooklyn existence: a proto-eco-hipster.

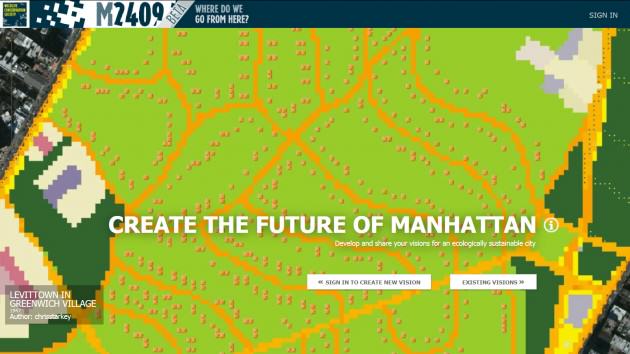

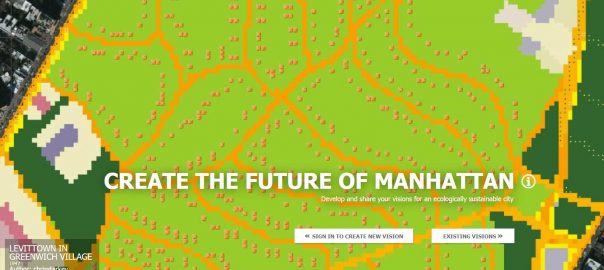

Thoreau would come to the city to explore the possibilities. For modern day explorers, we’ve constructed a portal to help people see and shape the nature of the city: Mannahatta2409.org.

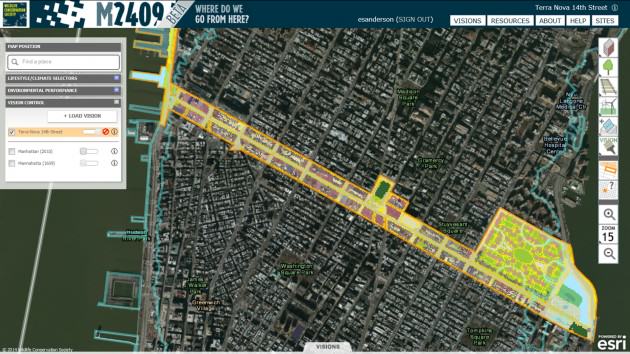

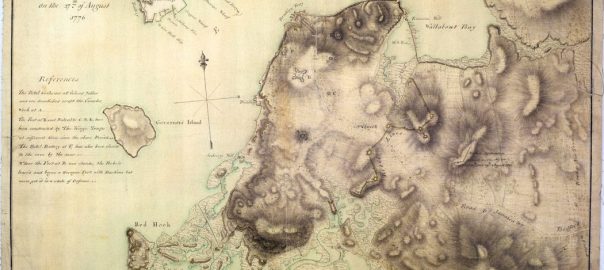

Mannahatta2409.org is a visionmaking tool. “Visions” are composed a combinations of ecosystems, lifestyle choices, and climate scenarios, where ecosystems include buildings and streets as well as forests, wetlands and beaches. Based on these combinations, the mannhatta2409.org estimates metrics of environmental performance in four categories: water, carbon, biodiversity, and population. In all, sixty-five measures are calculated and compared over three time points: the user’s vision, the area of the user’s vision as it exists in Manhattan today, and the area of the user’s vision as it existed 400 years ago, before Thoreau or the city, when the island of Manhattan was called Mannahatta, an exemplar of the wilderness. (Read more here.) The goal is to test the bounds and find consensus about what the nature of the city should be.

Mannahatta2409.org is meant for everyone. Since the release of the prototype in January, about 10,000 visionmakers have included students, architects, scientists, urban planners, and lots of people we know nothing about. (It is the Internet after all.) Video tutorials are available. It’s free to use, fun to play. Visions are for dreaming, sharing, investigating, and discussing. Visions can be worked on privately for as long as you like, and then can be made public by flipping a digital switch. Each vision comes with a URL that can be spread by twitter or posted to Facebook and Google+.

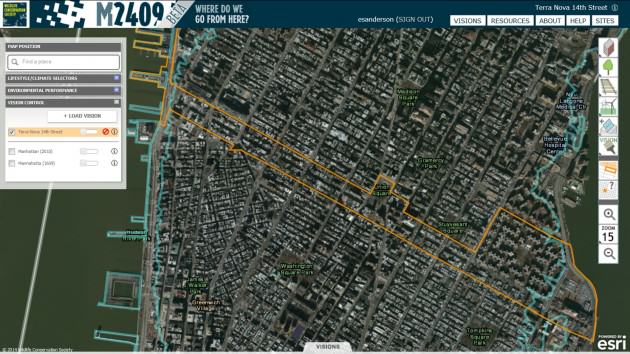

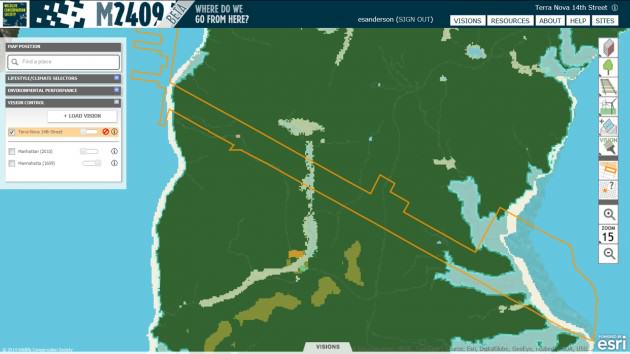

Here is an example: I used mannahatta2409.org to create a vision for Fourteenth Street in Manhattan with 90% less greenhouse gas emissions. I call it “Terra Nova 14th Street” because it deploys strategies from a book I wrote last year about making better cities: Terra Nova: The New World After Oil, Cars, and Suburbs.

The Terra Nova strategy is straightforward and effective: (1) use electrified transport, (2) generate as much renewable electricity as you can yourself, and (3) get the remainder from renewable sources elsewhere. Fourteenth Street is a main crosstown thoroughfare in lower Manhattan, dividing Greenwich Village from Chelsea and Midtown South. Mannahatta2409.org estimates that the blocks on either side of 14th Street house approximately 34,500 people currently (comparable to the US Census Bureau estimates), with about 18,700 working in that area. Average daytime densities top 49,000 people / square kilometer; nighttime densities (without workers) 30,000. Today the most common three ecosystems are sidewalks, boulevards, and apartment buildings. Four hundred years ago, oak-hickory forest, salt marshes, and the estuary existed in the same swath. The collected buildings, parks, and streets, and the energy production to supply them, produce an estimated 1.6 billion kilograms carbon dioxide per year, mainly from burning fossil fuels. On Mannahatta, in contrast, the trees and grasses took in one million kilograms carbon dioxide per year from the atmosphere, estimated as plant growth minus respiration.

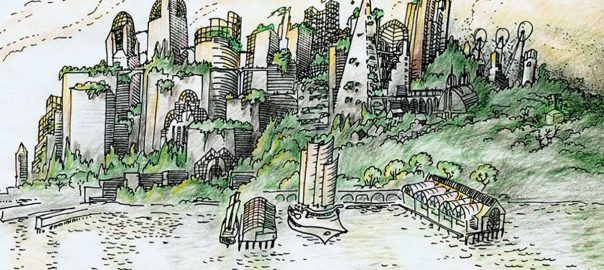

Terra Nova 14th Street replaces the four lanes of boulevard that currently constitute street with a light rail system, which connects with rail-lines on the Westside and the FDR Drive on the east, and streetcars on every other cross street, i.e., no cars. Bike lanes extend along 14th Street between the train and sidewalks in both directions. I painted photovoltaic panels on top of all of the buildings and added a windmill in a garden and tidal energy generator on the East River shore. Union Square Park is still green, but now with an oak-hickory woodland instead of a fenced off lawn and street trees. The trees also extend down the sidewalks in tidy rows to the island’s edge.

The most important alteration, however, was not ecosystemic, but rather lifestyle-oriented: my vision is inhabited by eco-hipsters. “Eco-hipsters” are one of the five lifestyles currently available through the interface (average New Yorker, average American, average Earthling, and Lenape person, a Native American tribe inhabited Manhattan in 1609, are the others). The eco-hipster lifestyle is based on the average New Yorker but with some tweaks to reduce environmental impacts. Eco-hipsters prefer to walk or bicycle over short distances and take the bus or subway over middling distances. On vacation, they ride the train. In town they heat and cool using electricity, living in slightly smaller apartments than the average New Yorker. (If that seems impossible, then consider the Lenape-standard dwelling with 50 square feet for a family of four.) However the most important choice that eco-hipsters make is to obtain all their electricity renewably from wind, solar, geothermal, or other real-time power generators. Electricity deregulation in New York and many other states makes this a matter of a phone call today.

The result, as laid out in the dashboard of environmental performance indicators, is 93% lower carbon dioxide pollution from 14th Street (106 million kilograms CO2 per year as compared to 1.6 billion kg CO2/yr) with a slightly higher population and nearly 10,000(!) more jobs. The economy of the future will thrive with eco-hipsters in charge. If those same people also rode all electric trains instead of partly diesel powered ones, then the greenhouse gas emissions could be brought to practically zero. The increases in green space and street trees also help absorb all the stormwater flows, at least for moderate precipitations events experienced with the baseline climate, defined for the years 1971 – 2000. (Feel free to suggest I use a changed future climate: mannahatta2409.org allows you to choose climate scenarios from 2020, 2050 and 2080, as well as 1609). Biodiversity is up in Terra Novan Manhattan, with habitat for an estimated 56 more types of plants and vertebrate animals than we have today, which is good, but still lags behind Mannahatta’s potential of 548 species in the same area.

Having constructed my vision in my own private workspace, the interface allows me to communicate my idea with the world. In the “Manage Saved Visions” dialogue, a switch attached to each vision is labelled: “Share with:.” The options are “me” or “everyone.” Others are free to view, probe, and analyze all the visions that have been shared. If they disagree, they can copy the vision into their own workspaces and modify it using the same ecosystem painting tools I used, re-publishing with the switch to everyone else. The goal of mannahatta2409.org is to obtain as many visions as possible of Manhattan (and eventually other parts of New York City) and then from those visions to develop some notion of what future we all want to create. Levittown in Midtown? Predator Cities? Eco-hipster-ville? Walden Pond? It’s really up to us.

To be fair, when Thoreau did visit in New York City in 1843, he found it a difficult place, mean, crowded and expensive. He wrote his friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson, “But I must wait for a shower of shillings, or at least a slight dew or mizzling of sixpences, before I explore New York very far.” (Many New Yorkers still share the same sentiment.) What Thoreau did like was the beach nearby, on Staten Island. “The sea-beach is the best thing I have seen. It is very solitary and remote, and you only remember New York occasionally. The distances, too, along the shore, and inland in sight of it, are unaccountably great and startling. The sea seems very near from the hills, but it proves a long way over the plain, and yet you may be wet with the spray before you can believe that you are there. The far seems near, and the near far.”

Cities that work with nature not against it seem far away, but I think they are nearer than we imagine.

Eric Sanderson

New York City

Acknowledgments: Mannahatta2409.org (version 1.0) was created by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). WCS envisions a world where wildlife thrives in healthy lands and seas, valued by societies that embrace and benefit from the diversity and integrity of life on‑earth. Development of the forum has been generously supported by the Rockefeller Foundation’s New York City Cultural Innovation Fund, the Biomimcry 3.8 Institute with support from the Summit Foundation, and the Bay & Paul Foundation. Terrapin Bright Green and the City of New York’s Department on City Planning advised on the project. In-kind support for GIS analysis has been provided by esri through an arrangement with The Nature Conservancy. We continue to seek support to improve and extend the website. If you would like to support the project, please contact us at [email protected].

Rebuilding Manhattan toward balance with nature is a supreme challenge. I’ve written the book “Los Angeles: A History of the Future.” It offers a practical scenario by which that car-crazy city could be transformed so that, after many decades, cars are gone and life is easier, greener and more fun. A source of employment for the next ten generations and a national purpose grander than shopping. http://www.issuu.com/metroeco/docs/lahof