(This encore publication originally appeared at TNOC on 21 August 2012.)

Walk through any major city and you’ll see vacant land. These are the weed lots, garbage strewn undeveloped spaces, and high crime areas that most urban residents consider blights on the neighborhood. In some cases, neighbors have organized to transform these spaces into community amenities such as shared garden spaces, but all too often these lots persist as unrecognized opportunities for urban improvement. In densely populated cities with sometimes few opportunities for new park or green space development, small vacant lots could provide green relief, especially in low-income areas with reduced access to urban parkland. (You can read the academic paper on this research here.)

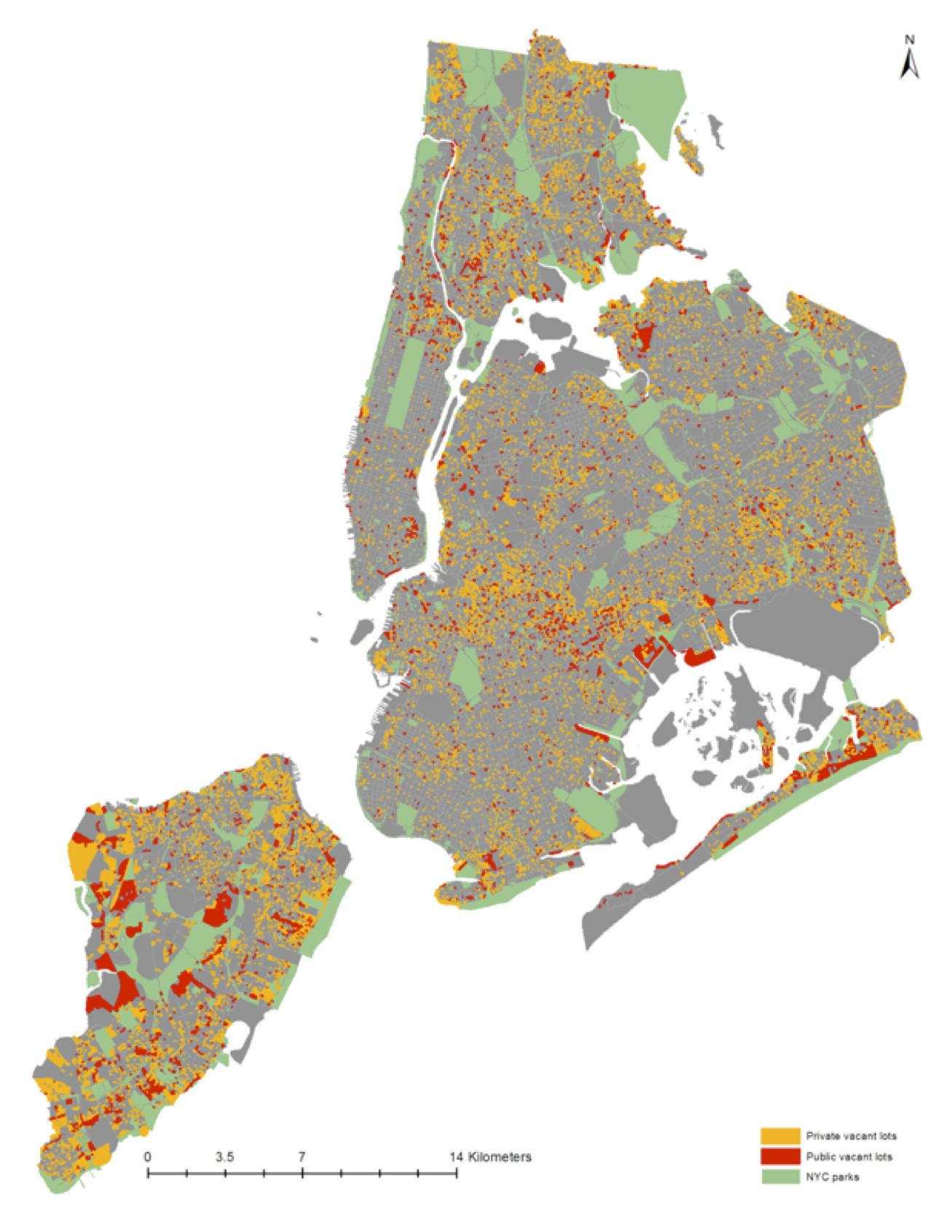

And yet, few cities are taking advantage of these underutilized spaces to improve urban biodiversity and provide additional ecosystem services. What’s even more surprising is the vast amount of urban land that is categorized as vacant. Take New York City for example: in this urban metropolis there are 29,782 parcels designated by the city tax code as vacant within the city boundaries, not counting vacant land in the surrounding suburbs and exurbs. This totals more than 7,300 acres of land that could be providing important social and ecological benefits for urban residents.

Here is what we know: Local and regional urban ecosystems provide important services that urban residents rely on for daily living. For example, ecosystems can supply clean water, produce food, absorb air pollution, mitigate urban heat, provide opportunity for recreation, decrease crime, and more. A recent publication from TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity) details the list of ecosystem services that can be provided by urban ecosystems.

And yet, all cities do not have the same level of food production, clean water supply, or air pollution removal. Different levels of ecosystem services among cities are due to a myriad of reasons. However, research is beginning to make clear that to improve urban sustainability and resilience city planners and policymakers need to strategically develop and manage the ecological resources within the city to meet the needs of expanding urban populations.

To improve the quality and quantity of ecosystem services that cities can reliably depend on, and given the financial difficulties most cities are facing, we need to find the low cost investment/high rate of return urban spaces where urban biodiversity and ecosystem services can be improved. These have to be spaces where people can interact with people (a component of ecosystems) and where people can interact with other components of ecosystems (air, soil, water, plants, animals). It’s also important for us to better understand urban people-nature dynamics (also termed social-ecological dynamics), which are about how interacting social and ecological components of ecosystems change over space and time and, for me anyway, understanding what these changes mean for future urban sustainability and resilience.

Lots of vacant land

One of the results of rapid population shifts in cities is the abandonment of previously occupied land. You can see the effects of this in older cities just by walking around. It is nearly impossible not to find land that is vacant in a city, regardless of whether you are in New York, Berlin, Sao Paulo, Shanghai, or Jerusalem. Vacant land typically results from human migration, deindustrialization, environmental disaster, decreased birth rates or contamination, and occurs at various concentrations in cities across the world. Though all cities have vacant land, some have more than others. In some cities the amount of vacancy is tremendous, such as in Detroit, Michigan (USA) where nearly one third of the city is vacant land.

So, why am I so captivated with these overlooked, unmanaged, vacant spaces in cities, especially considering that they are not the most pleasant places in which to conduct research? For one simple reason: vacant, underutilized land has the potential to provide cities with opportunity to create and develop new ecosystems that support biodiversity and increase the provisioning of vital ecosystem services for urban residents. Vacant land is ripe for transformation into more sustainable, resilient urban forms. I’m not the only one who is thinking along these lines. Urban ecologists have long recognized that the ecology in the city is not relegated to parks and protected natural areas, but exists everywhere: on rooftops, in sidewalk cracks, in backyards, in soils, rivers, and streams, in narrow green islands between streets, and also in vacant land areas.

[Interesting side note: Urban ecology as a discipline basically started with the study of plant communities on vacant land in European cities. Urban botanists in Berlin and other European cities studied the response of urban plants on “ruderal” bombed sites following World War II. These vacant sites, often consisting of rubble from destroyed buildings, provided warm, dry conditions for locally adapted plants to occupy.]

Researchers have noticed that vacant land in cities is created by a variety of urban processes, including deindustrialization, demographic and preference-based residential shifts, suburban expansion, and relocation of the work force. When my lab at The New School in New York City reviewed the literature, we noticed that the proportion of vacant lot area to total land area in large U.S. cities is relatively persistent, especially along the East Coast and Midwest of American cities, and remarkably, does not appear to be related to population growth.

Vacant lands constitute a large fraction of urban land area. In fact, vacant land in U.S. cities of more than 100,000 people varies between 19 and 25% of total land area — our research papers are in review in journals now — while for cities with populations greater than 250,000, vacant land makes up between 12.5 and 15% of total land area. The fact that the proportion of urban vacant land is fairly persistent in spite of population growth implies that vacant land may be a lasting phenomenon in urban areas, at least in the United States, and suggests that we need to be doing a lot more to manage these spaces to meet the current and future needs of urban nature and urban residents.

Vacant lots as opportunities

Another persistence is the way people tend to think about vacant lots: as areas associated with crime, abandonment, depressed real estate values, trash, overgrown weeds, pests, and general economic and/or social failure. Most people consider vacant lots to be negatively impacting community vitality.

I want to offer a challenging perspective, which is that we begin viewing vacant lots as opportunities for land use transformations that can contribute to community development. Vacant land in cities could provide important social and ecological benefits, including habitat for biodiversity, provisioning of ecosystem services, and new green space for residents in underserved neighborhoods of the city.

Given global urbanization trends compounded by the effects of climate change and other environmental pressures that are fast approaching or even exceeding planetary boundaries, one could argue that the primary dynamic that must be understood for increasing urban sustainability and resilience is the social-ecological relationships between humans and urban ecosystems.

Most humans are urban residents now. Which means, if you grow up in a city, your understanding of, and connection to, nature comes through interaction with urban nature. So, what is the state of our urban nature? Is it up to the task? Future decisions about how we steward our planet will likely be made by urbanites. What will their view of nature be? We don’t have answers to these questions yet, though the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity has recently launched a series of comprehensive publications to try to get a handle on the state of urban nature. However, many of us in the field of urban ecology and related disciplines would probably argue, first, that there is already amazing nature in cities, and second, that this nature is often overlooked, under-managed, misunderstood, abused, neglected, or wiped out for development. In any case, if we can agree that the current state of urban nature is not necessarily the ideal state for increasing the connectedness between people and ecosystems and for providing high quality urban living environments for human well-being, then where are the opportunities for making improvements?

Clearly, vacant land is an opportunity, and it’s time to seize it.

The benefits of vacant lot transformation

Here is a short list of the potential benefits that small investments to transform vacant land into more useful spaces could provide to cities:

- Stormwater absorption

- Air temperature regulation

- Wind speed mitigation

- Air purification (pollution absorption)

- Carbon absorption

- Flood control

- Habitat for biodiversity (e.g. plants and pollinators)

- Green corridors between urban natural areas

- Recreation space

- Community garden space

- Social gathering space

- Temporary art installation space

- Crime reduction

- Noise reduction

- Neighborhood beautification

- Increased adjacent property value

- Sense of place

- Environmental education opportunity

- Sense of well-being

- Green spaces for low-income neighborhoods

- Residential and commercial building energy savings

However, the full ecological potential of the urban environment, especially in vacant land areas, is just beginning to be understood.

Some U.S. cities are beginning to get the idea. In Baltimore, Maryland, a city leading the way in urban ecological research by way of the long-term Baltimore Ecosystem Study, vacant land has been considered from the perspective of pockets for urban plant diversity. In Brooklyn, New York a non-profit group, 596acres.org, has mapped all the vacant lots in Brooklyn and is working with local neighborhood communities to turn these spaces into gardens; places not only for growing food, but also as social spaces for neighborhood residents. In Detroit, citizens, farmers, and entrepreneurs are turning vast amounts of vacant land into urban farms. And in Philadelphia, when researchers cleaned up and greened vacant lots, the crime rate fell.

At The New School in New York City, post-doctoral fellow Peleg Kremer and PhD candidate Zoé Hamstead have been working with me to map vacant lots to understand the social and ecological value of these spaces. Our goal has been to understand the combined value of urban vacant land in order to illuminate overlooked spaces in the city where policy and planning could simultaneously meet goals for biodiversity habitat, ecosystem services provisioning, and social justice. This work (currently in review for publication) shows that, at least for New York City, vacant lots are already providing a host of cultural, provisioning, and regulating ecosystem services.

For example, we were a bit surprised to find that most vacant lots are already relatively green. Trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants dominate the vacant lots we sampled. On the other hand, there were many vacant lots located in lower income areas where people lived with fewer parks and other green spaces, neighborhoods where existing vacant lots could be actively managed to provide new green infrastructure to meet community needs.

“Develop Differently”: If you have lemons, make lemonade

It’s interesting to look at just how many vacant lots cities have. Perhaps you should take a look at the tax code in your city to see how many spaces tax assessors identify as vacant?

In New York City, there are nearly 30,000 sites identified as vacant lots. Numbers like these demonstrate the vast potential for providing ecosystem services and new urban biodiversity habitats. But a significant requirement in making these services possible over the long term is to assure they are planning and management priorities, both at the city and neighborhood level.

Currently, there is very little management of urban vacant land. Since most vacant lots in New York are small (<500m2), they may not be easily developed into more traditional built infrastructure such as housing, retail, or other typical uses. Lots that are small in size or otherwise make development challenging present ideal opportunities to develop differently, by enhancing or preserving urban green infrastructure. Land that is topographically-challenging, for example, may be well suited as nature preserves, or oddly shaped lots may serve as greenways or small pocket parks with public access. Land near existing rail or other transportation corridors where other types of development are unlikely may serve as portions of greenways with pedestrian and bike access.

It is common to find vacant lots in both low and high-density residential areas. Some may be small lots, located in the middle of rows of low-rise and low-density residential streets. Others, as in the example of a New York City community garden in the photo below, are part of higher density residential area. The lot on the far left in the image above representing tree cover within a residential context serves as an example of the importance of the location context and spatial distribution of vacant lots. In this case, the relatively high ecological quality (e.g. green) vacant lot is immediately adjacent to a low-income, high population density neighborhood. This lot is also next to a large public open space (not shown) and provides a connection between open space to the southeast and street trees to the northwest. Such connections are crucial in the maintenance and provisioning of ecosystem services, as well as the maintenance of biodiversity that supports ecosystem services in cities. Vacant lots could serve as corridors and connectors between fragmented urban green spaces, improving the ability for species to migrate between the built infrastructures of the city.

The temporal perspective is also important to consider in addition to the spatial. For example, even if there is planned development for a particular vacant parcel, we should be considering the option of utilizing vacant lots — in the short, medium and long terms — as urban nature sites that provide and support ecosystem services. In a 2002 Planners Advisory Report of the American Planning Association (506/507 Old Cities/Green Cities: Communities Transform Unmanaged Land. J. Blaine Bonham, JR., Gerri Spilka, and Darl Rastorfer. March 2002. 123pp), the authors suggest that vacant land slated for eventual redevelopment should serve interim beneficial uses such as community gardens, wildlife gardens, public plantings and recreational areas so as to avoid the common blighting influence on the surrounding community. Community gardens, open spaces and other urban greening sites provide important cultural value in addition to ecological amenities such as food, air quality improvement and stormwater mitigation.

To develop differently, we need to plan and design urban spaces where ecological and cultural value can be intertwined. Importantly, as communities transform low quality landscapes into community gardens or other sites of community engagement, more resilient communities may emerge; communities that are better equipped to deal with future urban stresses. Community engagement that involves ecological resources may, in turn, perpetuate the development of ecosystem services and enhancement of community cultural amenities that continuously build both social and ecological resilience through a virtuous cycle. In this way, transformation of vacant land may provide an opportunity for enhancing the resilience of coupled social-ecological systems in urban areas.

There is still work to do to understand in detail how to best to use the cache of vacant land that cities have. Ecologists and social scientists could be very useful to planners, designers, and policymakers who are interested in transforming blighted urban spaces into social and ecological amenities. For example, differentiating vacant lot types according to how they are actually used, even if their use is temporary, can help planners identify target areas for improvement, as well as indicate possibilities for land transformation. Similarly, by assessing the size, location and shape characteristics of vacant lots, planners may be able to identify suitable spaces for various community purposes.

For instance, small, oddly-shaped lots along roadways with foot traffic may be best developed as pocket parks, while larger lots adjacent to residential buildings may be better suited for urban agriculture or neighborhood parks. Because most vacant lots are in residential areas, they can serve as spaces for community activities where people live, thus creating the potential to support neighborhood improvement and community engagement. Essentially, vacant lots could provide opportunity for developing social capacity at the same time that they provide new urban ecological infrastructure.

Frankly, vacant land has been overlooked for far too long. If cities were to invest in the social-ecological transformation of vacant land into more useful forms, they would be creating the potential to increase the overall sustainability and resilience of the city. Depending on the kinds of land transformations urban planners and designers dream up, vacant land could provide increased green space for urban gardening and recreation, habitat for biodiversity, opportunities for increasing water and air pollution absorption and many other regulating, provisioning, and cultural ecosystem services.

Community gardeners across the world have capitalized on the opportunities of urban vacant land for decades, and the rest of us should too.

Timon McPhearson

New York City

USA

For more information see:

McPhearson, Timon, Peleg Kremer, and Zoé Hamstead. “Mapping Ecosystem Services in New York City: Applying a Social-Ecological Approach in Urban Vacant Land.” Ecosystem Services (2013):11-26 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.005

Kremer, Peleg, Zoé Hamstead, and Timon McPhearson. “A Social-Ecological Assessment of Vacant Lots in New York City.” Landscape and Urban Planning (2013): 218-233 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.05.003

Leave a Reply