(This encore publication originally appeared at TNOC on 7 August 2012.)

I have long been a believer in E.O. Wilson's idea of biophilia; that we are hard-wired from evolution to need and want contact with nature. To have a healthy life, emotionally and physically, requires this contact. The empirical evidence of this is overwhelming: exposure to nature lowers our blood pressure, lowers stress and alters mood in positive ways, enhances cognitive functioning, and in many ways makes us happy. Exposure to nature is one of the key foundations of a meaningful life.

How much exposure to nature and outdoor natural environments is necessary, though, to ensure healthy child development and a healthy adult life? We don't know for sure but it might be that we need to start examining what is necessary. Are there such things as minimum daily requirements of nature? And what do we make of the different ways we experience nature and the different types of nature that we experience? Is there a good way to begin to think about this?

A powerful idea

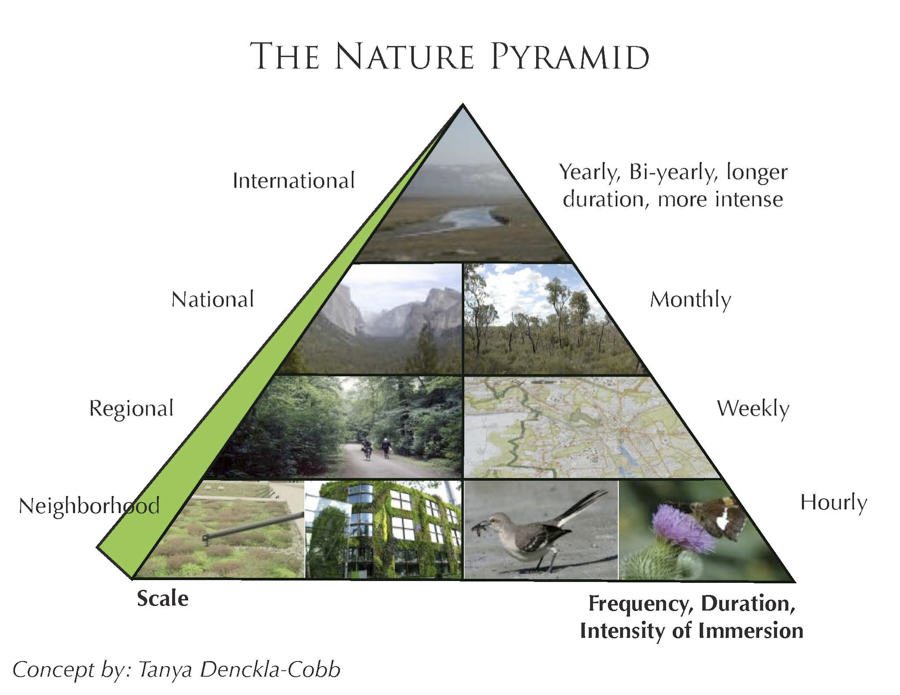

Here at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA USA), my colleague Tanya Denckla-Cobb has had a marvelous and indeed brilliant idea. Why not employ a metaphor and tool similar to the nutrition pyramid that has for many years been touted by health professionals and nutritionists as a useful guide for the types and quantity of food we need to eat to be healthy. Call it, as Tanya does, the Nature Pyramid, and we have something at once novel and attention-getting, but potentially very useful in helping to shape discussion about biophilic design and planning. Towards the top end of that nutritional pyramid, as we know, are things that, while important to overall nutrition—meat, dairy sugar, salt—are less healthful in larger quantities and should be consumed in the smallest proportions. Moving down the pyramid are elements in the diet—fruits and vegetables—that should be consumed more frequently and in greater quantity, and then finally, grains that provide healthy nutrients and carbohydrates that are needed on a daily basis. The Nature Pyramid would work in a similar way. I have taken a stab at what the nature pyramid might look like, presented in the graphic below. It is a bit different than Tanya’s initial idea, but a version I am convinced will be highly useful as a way to begin to explore and discuss the amounts and types of natural experiences we need to live a healthy life.

The Nature Pyramid, then, challenges us to think about what the analogous quantities of nature are, and the types of nature exposures and experiences, needed to bring about a healthy life. Exposure to nature, direct personal contact with natural is not an optional thing, but rather is a necessary and important element of a healthy human life. So, like the nutritional pyramid, what specifically is required of us? What amounts of nature, different nature experiences, and exposure to different sorts of nature, together constitute a healthy existence? While we may lack the same degree of scientific certainly or confidence about the mix of requisite nature experiences necessary to ensure a healthy life (or healthy childhood), as exists with respect to dietary and nutrition (and of course there remains much disagreement even about this), the pyramid at least begins to ask the right questions. It starts an essential and important conversation that needs to occur given our modern earthly circumstances.

The Nature Pyramid helps us to begin to think about what will be necessary to counter what journalist Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder” in his important book Last Child in the Woods (Algonquin, 2005; and further explored in his more recent book The Nature Principle, Algonquin, 2012). It is helpful for several reasons. First and foremost perhaps is the important message that, like one's diet, it is possible to act in ways that lead to a healthy mix and exposure to nature. This is subject to agency and behavior and responsible choice in the same way that the food pyramid guides eating. And, like the nutritional pyramid, the Nature Pyramid provides guidance to planners, designers and public decision makers. We have important choices about community design: what we choose or choose not to subsidize, what nature opportunities we want our children and adults to have available to them, and what steps might make a healthier biophilic life more feasible or possible.

What should make up the bulk of our nature diet?

At the bottom of the pyramid are forms of nature and outside life that should form the bulk of our daily experiences. Here there are the many ways in which we might daily enjoy and experience nature, both suburban and urban. As adults, a healthy nature diet requires being outside at least part of each day, walking, strolling, sitting, though it need not be in a remote and untouched national park or otherwise more pristine natural environment. Brief experiences and brief episodes of respite and connection are valuable to be sure: watching birds, hearing the outside sounds of life, and feeling the sun or breeze on one's arms are important natural experiences, though perhaps brief and fleeting. Some of these experiences are visual and we know that even views of nature from office or home windows provides value. For school aged kids spending the day in a school drenched in full spectrum nature daylight is important and we know the evidence is compelling about the emotional and pedagogical value of this. Every day kids should spend some time outside, sometime playing and running outside, in direct contact with nature, weather, and the elements.

Moving from the bottom to the top of the pyramid also corresponds to an important temporal dimension. We need and should want to visit larger more remote parks and natural areas, but for most of us the majority of these larger parks will not be within distance of a daily trip. At the top of the pyramid are places and nature experiences that are profoundly important and enriching, yet are more likely to happen less frequently, perhaps only several times a year. They are places of nature where immersion is possible, and where the intensity and duration of the nature experience are likely to be greater. And in between these temporal poles (from daily to yearly) lie many of the nature opportunities and experiences that happen often on weekends or holidays or every few weeks, and perhaps without the degree of regularity that daily neighborhood nature experiences provide.

Like the food items higher on the food pyramid, the sites of nature highest on the Nature Pyramid might best be thought of occasional treats in our nature diet—good for us in small and measured servings, but actually unhealthy if consumed too often or in too great a quantity. For many urbanites from the industrialized North, large amounts of money and effort are expended visiting remote eco-spots, from Patagonia, to the cloud forests of Costa Rica, to the Himalayas. It seems we relish and celebrate the ecologically remote and exotic. While they are deeply enjoyable nature experiences, to be sure, they come at a high planetary cost, as the energy and carbon footprint associated with jetting to these places is large indeed. No longer are such trips appreciated as unique and special “trips of a lifetime,” but fairly common and increasingly pedestrian jaunts to the affluent citizenry of the North. The Nature Pyramid sends a useful signal that travel to faraway nature may as glutinous and unhealthy as eating at the top of the food pyramid.

Another message is that a diversity of nature experiences will yield a healthy life, in the same way that a diversity of foods and food groups leads to a healthy diet. The middle of the pyramid suggests the need for larger local and regional green spaces that provide more respite and deeper engagement than street trees or green rooftops might. They can be visited less frequently, but perhaps with greater duration and intensity, say on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. The Nature Pyramid allows us to imagine lives lived mostly in urban (albeit green urban) environments but with some substantial amount of time spent in more classically natural environments around and outside cities. The pyramid lets us begin to imagine—as we imagine the combinations of food and types of food that go into our daily and weekly diets—the combination of different nature experiences essential to a healthy human life.

Overcoming the nature-urban dichotomy

The Nature Pyramid encourages us to overcome the paralysis of the modern urban-nature split that many of us perceive. For example, the United States is an urban population, for the most part: more than 80% of Americans live in metropolitan areas. Cities and urbanized areas typically provide less direct contact with the kind of pristine nature we often think we need. There are good and important reasons we live in cities, and from the perspective of sustainability and sustainable living, cities are an essential aspect of effectively addressing global environmental problems. Yet, the types of nature found in cities are more fragmented, smaller and generally allow less and shorter kinds of immersion than, say, camping in a remote wilderness area or spending several days in a national park. But as the planet continues to become more urban the challenge of providing the essential minimum dosage of nature becomes an increasingly important challenge everywhere.

Many of the techniques currently used to green urban environments provide value—"nature nutrients" if you will—in the lower rungs of the pyramid. Green design features such as eco-rooftops, bioswales and rain gardens, community gardens, trees and tree-lined streets, and vegetation strips and urban landscaping, provide valuable ecological services (from retaining stormwater, to moderating the urban heat island problem, to sequestering carbon), but they also provide urban residents with exposure to nature, albeit in a human-altered context. The pyramid helps us see how the daily consumption of and exposure to the myriad green features of cities provide, like a balanced food diet, a healthy mix of nature experiences. I know in my own case I notice and enjoy the circling turkey vulture, the ant life and invertebrate antics below foot, the sounds and sights of the not insignificant green strips and edges that I walk by on my way to work and on walks through my neighborhood. I might be happier (and healthier?) if my nature experiences were deeper in time or quality, but these fleeting and fragmentary episodes of a green urban life are valuable and indeed make up the bulk of my daily nature experiences. The Pyramid helps us appreciate the valuable exposure to many smaller green features and nature episodes in the course of a day, and importantly, the need to include these features in urban design.

Thinking About “Servings” and “Nutrients”

There are many unknowns in this conceptual framework, of course, and many open questions. But the Nature Pyramid is valuable in identifying and framing these important questions. One interesting question is how we measure the “servings,” if you will, of nature exposure in this nature diet. What is the unit of measurement that we ought to speak of in terms of a nature experience; say a walk or other time outside that takes twenty minutes or a half an hour, or something qualitatively different, say a momentary sighting of a bird, or tree, or distinctive mushroom. Is a ten-second glance out the window at work onto a verdant courtyard adequate to compose a “serving”? Is the momentary wonder at the interaction of two birds, at the joyous sight of a circling hawk, the scolding chatter of a squirrel as you pass by that corner lot with the large trees a useful serving? And how, over the course of an hour, an afternoon, a day, do these servings add-up to or accumulate to form the nature nutrition we need?

Often our nature “servings” don’t nicely fit into any description of an event or episode, and are more continuous, less discrete: for instance the aural background of natural sounds, the katydids, tree frogs, crickets that compose the night soundscape that many of us find so replenishing and soothing. One’s day is, in fact, made up of unique and complex combinations of these nature experiences (or they should be), some fleeting and momentary, others of longer duration and intensity. The Nature Pyramid helps us, at least calls upon us, to develop some form of metric for understanding this richness and complexity and to understand how (or not) these different experiences add up over the course of a day, week, month or year to a healthy life in close and nurturing contact with the natural world.

And there are other important open questions highlighted by the Nature Pyramid. Is it possible to imagine more intensive, immersive nature experiences even in normal everyday urban environments; urban places and smaller urban environments that may deliver the restorative power of experiences higher on the pyramid? And can we design them in ways that intensify these experiences? A brief visit to a forested urban park, or botanic garden, could in theory permit an immersive experience equal to more distant forms of nature. Again, these are important questions that the framework of the Nature Pyramid helps us to identify and focus on.

The Nature Pyramid encourages us to look around at the actual communities and places where we live to see if they are delivering the nature nutrients and diet we need. Yale professor Stephen Kellert argues that we need to overcome the sense that nature is “out there, somewhere else,” probably a national park, and what we need today more than ever is “everyday nature,” the nature all around us in cities and suburbs. Much is there, of course, if we look, but we must also work to enhance, repair and creatively insert new elements of nature wherever we can, from sidewalks to courtyards, from alleyways to rooftops, from balconies to skygardens. Less frequent perhaps are the deeper and longer episodes—the visit to a regional park, the longer hike along a nature trail or through a regional trail or greenway system beyond one's immediate neighborhood. These experiences might for some happen daily, but likely don't. They are more infrequent, tending to occur more on a weekly than daily basis. There are several nature trails my family visits and hikes on weekends, and they form a part of our healthy nature diet.

We can quibble, certainly, about what the appropriate mix of nature experiences is or ought to be, to ensure health and well-being—how much of our day should be about experiencing nature through an outdoor walk on a trail or in a park, versus contemplating a beautiful view of a river or forest from an indoor room or balcony? But the pyramid most importantly helps us to see that for most individuals, living a healthy urban life in touch with nature is a function of the daily, weekly, and monthly (and even less frequent) nature experiences we have. Ensuring that we provide the minimum dosage or serving of nature should be a priority for all planners and designers.

A rich research agenda

While the Nature Pyramid already provides us with important policy and planning insights and guidance, there are clearly many important open questions and a significant (and exciting) research agenda that flows directly from it. Addressing these questions will require the good work of researchers in a number of disciplines, including medicine and public health, psychology, and of course the design disciplines of landscape architecture and city planning, among many others. The research questions are not easy ones, as this essay has shown, but are in fact rather complex. There is a need to focus at once on the natural elements and processes of neighborhood urban nature (trees, birds, gardens), the different ways in which these elements are experienced or enjoyed (listening, seeing, digging in soil), and the many factors that may influence their emotional import and “nutritional value” (are they experienced alone or enjoyed with others, with friends and family, for example). And there is a need to better understand and describe more precisely the outcomes or benefits delivered, i.e. the ways in which exposure to nature makes us happier and healthier.

And there are complex behavioral cascades that will need to be better understood. If we feel happier when we see trees and vegetation in our neighborhoods, for instance, we are more inclined to spend time outside and engaged in walking, strolling, hiking and other physical activity, in turn delivering important physical health benefits. Some studies already confirm this. Equally true, trees and nature create context for socializing, thus in turn delivering important emotional benefits (and we already have considerable evidence about the many health benefits of friendships). So the research task becomes one of better understanding how and in what ways the nature in cities can set in motion other positive health outcomes (and again, which natural elements, experiences, features, or processes, and in which combinations, will trigger these valuable cascades).

Some of this research is already underway through our Biophilic Cities Project, here at the University of Virginia, with funding from the Summit Foundation and the George Mitchell Foundation. Much of our work has focused on learning from emerging biophilic cities around the world, and the tools, techniques and ideas these exemplary cities are employing to deliver nature to their citizens, and to foster connections and contact with the nature. We have partnered with some exemplars of urban nature, including Singapore, Portland, San Francisco, and Oslo, among others. But soon we will also be attempting to tackle the question of the minimum daily dose of the natural world. We are planning to consult leading researchers in medicine, public health, and other fields about the question of minimum levels of nature, through the use of a Delphi process, and to explore whether there might emerge some areas of early consensus about what kinds and amounts of nature urbanites need.

We are also beginning to work with our colleagues in psychology to better understand the comparative emotional and restorative value of different combinations of urban nature. But this work is just a beginning, and we will need many colleagues, in many allied disciplines, to join with us in this important work. While we know much, there is so much more to do, and so much exciting research to at least begin in the next few years. The Nature Pyramid, rather than being an answer or a complete and fully-developed model, is but the beginning point, a provocation to explore and innovate and better understand the important ways in which everyday, neighborhood nature can help deliver the essentials of a happy, healthy and meaningful urban life.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

I”m about to run a workshop here in Sydney, Australia, on 25 May, at Vivid Ideas Festival, called “Contemporary Currencies: Does money still matter most?” with the provocation, “Or, are our attention, time, energy and values equally if not more precious?” The focus for the workshop is on How to ensure the future relevance, and therefore viability, of a place or space and nature?” I’ve found so much value in reading your post and will highlight it in my workshop. For example, in relation to the fragmentary way most people in cities experience nature, giving it attention (#1 currency) is more important than time. We don’t need to spend a lot of time in nature, we have to, as Linda Stone would put it, use our attention intentionally, to ensure we get the full benefit.

What a fantastic concept! I fully agree with the arrangement of the Nature Pyramid and can see this model working very well from my own experience. For instance, I definitely gain tremendous well-being when I spend time in wild nature (i.e., the domain of large carnivores where wit, intelligence and skill are required if true enjoyment is possible). Travelling to and spending time in awe-inspiring natural areas inevitably leaves a mark on us, too, equivalent in my experience to a milestone in personal history.

Isn’t it interesting, though, how the opposite is not true, in terms of intuition? I’m a plant ecologist and know that spending time in nature is good for me in myriad ways, yet why do I only notice my nature deficit when I’m out there, taking care of it? Why do I not realize when I’m stuck in the city/ office and really ought to put in the effort to get out?

Many thanks for sharing this, and kind regards 🙂