Green roofs are becoming more popular around the globe and are considered to be a very progressive landscape design devise in urban areas. The green roof has started to become fashionable—it is even considered as one of the “compulsory” sustainable buildings features and an important part of urban green infrastructure. For example in Germany and Sheffield building companies are requested to establish green roofs on new buildings.

In the last two decades, the technology of creating green roofs has become standardized. The most popular today are extensive green roofs with a thin substrate layer and several succulent drought tolerant species such as Sedum and Sempervivum. These plants have become among the most popular because of their low cost, simple installation and basic maintenance. The Sedum green roof industry is quite established in the US, Canada, Germany, UK and Scandinavian countries. In Germany it is estimated that 25% of rooftops are covered with green roofs.

However, the commercialization of green roof technologies and mass production is leading to homogenization of green roofs—they all look the same, with a limited number of Sedum species—and a decrease in their ecosystem service potential. The Sedum green roof’s main function is runoff regulation and is not particularly effective in serving as biodiverse biotopes due to the homogeneity of plant material.

The most recent trend in ecological design is creating biodiverse green roofs that can be seen as a valuable urban biotope and substitute of the lost terrestrial habitat during building construction process. In this sense the Scandinavian vernacular experience of green roofs can be a very valuable foundation for modern researchers and designers.

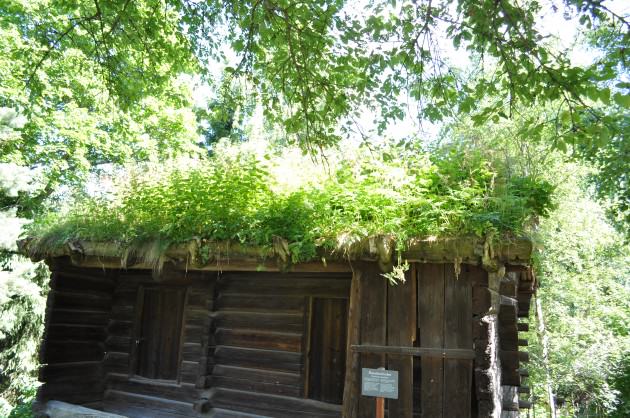

Scandinavian turf roofs of the 20th and 21st centuries can be assumed as the historical analogue of modern extensive green roofs. Turf roof or “torvtak” (in Swedish and Norwegian) is a traditional roof type of Scandinavia. In contrast to an ecological and esthetical purpose of vegetation on modern green roofs, turf was supposed to be a strictly utilitarian and to protect the waterproof layer made of birch bark sheets. It was the common way to construct roofs for timbered houses in Scandinavia up to the end of the 19th century.

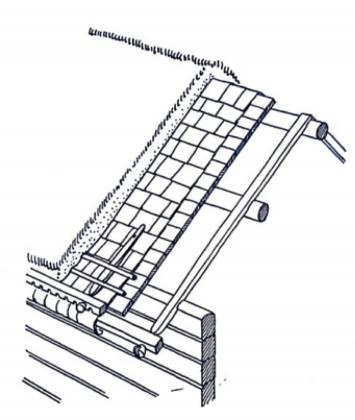

A similar roof type was used for the Far East vernacular houses in order to protect them from the rain damage. The technology of Scandinavian turf roof implies the construction of several layers with broad sheets of birch bark laid on roof surface made of wooden planks. Two layers of natural sod are laid on the birch bark sheets. In Sweden the turf was simply cut from the meadows or forest margins and placed on roofs. The load from a roof was about 250 kg per m², which contributed to the shrinkage of wooden logs. Winter weight of the roof could reach 400-500 kg per m² because of snow. In addition, the turf had insulating properties, which was another advantage in a cold climate.

The technology of such green roofs is quite simple. Wide sheets of birch bark are stacked on the sloping roof of the boards in several layers. Turf is laid directly on the bark in two layers. The first layer is laid back up to the dead grass so it can serve as drainage. The second layer is laid on this first layer. Eventually the roots from both layers bond together. A layer of bark served an average of 30 years, and then it had to be replaced.

Since the materials for the construction of sod roofs can be found all over the place, construction was not costly. Construction was carried out by the family or with the help of neighbors.

Meadows had, and have, very high biodiversity and this particular point makes old experiences so valuable for modern landscape design practices. These native turfs perfectly reflect the “genius loci”, which is the main motto for searching in modern landscape architecture practice.

Turf roofs include a high variety of native meadow plant species. They are ideally fit to local climatic conditions. Torvak is a very attractive place for invertebrates, a variety of insects (including beetles, spiders, ants and bees), and some birds.

Even though today in Scandinavia Sedum green roofs are dominant type, there is growing tendency to use biodiverse green roofs. The main supplier for traditional green roofs in Sweden is “Pratensis” nursery. This firm is specialized in growing herbaceous seed mixtures from local genetic material for biodiverse green roofs and alternative lawns (meadow like plant communities).

We researched several traditional Torvak in Stockholm (Skansen Open Air Museum) and Uppsala (Disagården Open Air Museum). These green roofs were established around 40 years ago. The aim of our research was to develop a plant compositions and recommendations for the creation of sustainable plant mixtures for nurseries for different light conditions and orientations of the roof slope. We found 76 species of higher vascular herbaceous plants.

Our observation leads to the conclusion that the similar green turfs, which were harvested in the same habitats but placed on the roofs with different microclimates, are going through several stages of ecological succession. The nature and speed of these changes depend on the light conditions, the presence of trees in the immediate vicinity that create shade and reduce air flow through the area. There was quite clear division on “open” and “shadowed” green roofs where the differences in plant compositions were quite distinctive.

Based on our research we recommend quite a long list of plants for sustainable biodiverse green roofs.

We also established an experimental biodiverse green roof in the summer of 2012 at SLU Campus in Ultuna, Uppsala. Cut turf from different native plant communities from the Uppsala area was placed on the roof of two story building.

There was no watering or any other maintenance operation with these plantations. Exceptionally hot summer of 2013 contributed to the loss of most grass species. However there were quite a few perennials and annuals successfully outlasted this draught, then flowered and produced seeds.

In modern conditions it is not advisable to use the cut turf from native meadows as it was in past time even in the countries such Sweden or Russia with available native plant communities. In absence of watering and maintenance the original native composition can be changed quite quickly and does not fulfill the desirable functions (including decorative appearance). The most effective and economic way is using rolled biodiverse turf from special nurseries.

Our research here begs an important question: how can designers and ecologists find, in each bioregion, ecological communities that would be appropriate for biodiverse green roofs, and apply them to the right structural engineering. Then we could develop a paradigm for locally-sourced, native-species, biodiverse roofs everywhere.

Maria Ignatieva and Anna Bubnova

Uppsala

about the writer

Anna Bubnova

Anna Bubnova is working on an investigation of Green Roofs from the perspective of biodiversity and sustainability and completing her PhD thesis.

Leave a Reply