“We will never forget.” After September 11 (2001), this claim was made in countless political speeches, memorial eulogies, bumper stickers, carved stones, tattoos, and tee-shirts.

But we do forget. Time rolls on. We age. New people are born who have no lived experience of the tragic occurrences of that day. So too, does the landscape change. New buildings rise, trees grow, roads are built. We exist in an on-going cycle of disturbance and recovery. As such, our lives and our landscapes are constantly shifting in new and different ways.

So what happens to the places that were purposively set-aside as spaces of remembrance? How do they change or persist? What role do they play in the lives of their creators, their stewards, and their users as we move further in time away from a particular event? These are the questions that we are exploring as we re-visit sites associated with the Living Memorials Project. These sites are community-based memorials that use nature (from single tree plantings, to park dedications, to forest restoration projects, to labyrinths, to community gardens) to commemorate September 11, 2001.

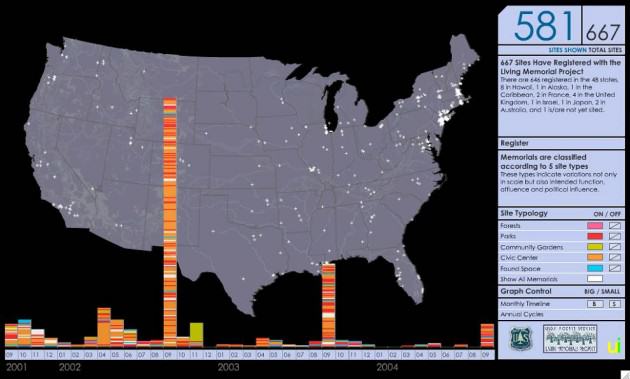

Living memorials exist all across the country, but are concentrated in the areas surrounding the crash sites: the New York City metropolitan area, the Washington, D.C.-Virginia area, and near Shanksville, PA. Many of them were created in the immediate days and months following September 11, on much quicker timelines than the formal, state-led built memorials that are now dedicated and open to the public at these sites. The Living Memorials Project was funded by the USDA Forest Service to provide community grants to stewardship groups and conduct research to understand changes in the use of the landscape post-September 11. In many cases, the creation and maintenance of these sites was led by civic groups—from informal groups of friends to formalized nonprofits—who sought to create a more immediate, accessible, and local response to the event. (To search a list of these sites, visit the National Registry. To read 12 journeys through these Living Memorials, visit Land-Markings. To learn more about the social meanings of community-based memorials in the ‘pre-memorial period, read this article.) So, unlike the Gettysburg Battlefield or the built monuments on the National Mall that are meant to remain in perpetuity in a fixed image, these sites may be more malleable in response to local changes and needs—both because of their physical form as nature-based sites and because of their governance as often civic-led spaces.

Starting next year, we plan to systematically return to a sample of the 113 stewardship groups that we interviewed and the nearly 700 sites that we documented nationwide. We began that process earlier this summer at the request of documentary filmmaker, Scott Elliott, who is creating a film called The Trees. In seeking to tell the story of the memorial forest at the World Trade Center, Scott learned of the hundreds of community-based sites that use trees, plants, and nature to memorialize the event and wanted to visit a few. So we selected two sites in the New York City area that we hadn’t formally interviewed or interacted with since 2006, not knowing what we would find.

The trip inspired us as researchers about the power of these sites and reinforced some important lessons about community stewardship as it persists over time. In particular, our visits to two sites have reinforced our appreciation for the persistence, responsiveness, and adaptability of civic stewardship. We see that community-managed spaces can be sustained throughout the passage of time, changes in leadership, changes in the economy, and even changes in climate. We’d like to share some reflections….

Tribute Park, Rockaway, NY

One common concern about community-led stewardship is that it is temporary or fleeting—as many informal groups are small in terms of staff and budgets, are volunteer-powered, and lack the institutional authority of government. Yet, Tribute Park shows the persistence of community stewardship even in the face of leadership transitions and major disasters.

The site was created, starting in 2002, by the local Chamber of Commerce. It was a vacant, waterfront lot, on the Jamaica Bay side of the Rockaway Peninsula. Just blocks from the busy, public beach on the Atlantic Ocean side, the Bay side of the Peninsula always offered a more quiet space for interacting with nature through viewing, fishing, and crabbing. On September 11, members of the public gathered along the bay, including at the vacant lot, to view the smoldering World Trade Center (WTC) towers. The Chamber of Commerce envisioned a contemplative space that would reflect the seaside character of the Rockaways and would uniquely commemorate the victims of the Rockaways. The peninsula lost a number of residents that day—including many members of the uniformed services—as well as downtown workers in New York City’s financial district.

Since then, a new group has emerged to tend the site—The Friends of Tribute Park. Still powered by volunteers, many of whom are retired residents of the Rockaways, the care for the site is clear. They have added new elements to the park—including a piece of WTC steel that they had to go to court in order to secure and install. Every Tuesday morning, from 8:30-10:00am—in remembrance of when the planes struck the WTC towers, they hold volunteer stewardship days, where anyone from the public can come and help take care of the site. Bernie Coburn of Friends of Tribute Park called the site a “hands on park” that will keep changing over time as the group works to “maintain beauty with a personal touch.” When asked whether he considers the site a sacred space, he said that it was, because it is “a living project—I live for it.” Clearly, the ongoing stewardship and maintenance of the site—perhaps more so than the physical form or the symbolism or design—makes the site sacred.

The site also endured and persisted through Hurricane Sandy, which inundated the entire peninsula of the Rockaways. While many residents were struggling to rebuild their homes and restore their lives, stewards also took the time to help restore Tribute Park—because they knew that the site was an important gathering space and community resource that merited rebuilding. In addition, the NYC Parks Department provided crucial personnel and heavy equipment, showing that civic stewardship does not work in the absence of government support. Indeed, the volunteers told us that NYC Parks’ crews visit the site weekly to assist with maintenance of the site. While the initial creation of the park was civic-led—with civic stewards operating as a unique form of “first responder” to the 9/11 tragedy, they still work in partnership with state through grant funding, regulatory compliance, and general maintenance. We see that these public-private partnerships exist at many scales and in many contexts. Just as the flagship parks of Central Park and Prospect Park have their prominent private partners—the Central Park Conservancy and the Prospect Park Alliance, so too does this tiny, 30,000 square foot site have the Friends of Tribute Park, which ensures its care and upkeep.

New Jersey’s Grove of Remembrance, Liberty State Park, Jersey City, NJ

Community-based stewardship is often expressed in vacant lots and community gardens—sites that are outside the reach or care of the state or the market or that are deliberately managed via community control. Discussing the case of the North Brooklyn post-industrial waterfront in the 1990s, Daniel Campos writes about these moments in time and space as an “Accidental Playground”—where members of the public have the ability and autonomy to create, shape, and manage the use of space. Once the state and the market come back in, even in a case where a formal park is designated as it was in North Brooklyn—the role for the public tends to shift from creator/steward/manager to “user”. The Liberty State Park memorial, however, is a unique example of ongoing civic stewardship within a designated state park.

When community stewardship occurs on parkland, it can range from one-time, large-scale volunteer tree planting days to decades long dedication by ‘friends of the park’ groups, alliances and coalitions. The Grove of Remembrance at Liberty State Park was born out of the spirit of long-time community stewardship and created via hundreds of volunteer arborists, 9/11 family members, New Jersey residents, and Friends of Liberty State Park who came together to help plant this 10 acre former brownfield site with 691 trees (to honor all of the New Jersey victims who perished). These volunteer events are filled with the excitement and energy of getting hands dirty and “doing something.” Indeed, both authors participated in the planting of this site, and we feel materially and physically connected to its creation.

The ongoing care and attention of the nonprofit New Jersey Tree Foundation (NJTF) over the past 10 years has created opportunities for the public to continue to be involved. NJTF is primarily responsible for the maintenance of the site, though it is on state land, so we see an example of hybrid governance at work. Thus NJTF uses its own staff and its partnerships with civic, private, and school groups to help maintain the site. For example, NJTF has worked with area schools to use the grove as a space for environmental education. Area students learn about the life cycle of trees and plants, starting seedlings in their classroom, and then coming to the grove to engage in planting and maintenance.

Another pattern we see repeated with these sacred sites of social meaning: people go above and beyond their traditional professional roles and see their engagement with sites as a form of ‘giving back’ voluntarily. Working via NJTF, the professional arborist and forestry community in New Jersey has effectively “adopted” the site—donating thousands of hours of services, labor, and expertise. Like Tribute Park, the waterfront Grove of Remembrance was also flooded and heavily affected by Hurricane Sandy. The site is directly adjacent to a marina and after the storm, entire boats were found stranded and overturned inside the grove. Heavy equipment was required to remove the boats, remove the downed trees that could not be saved, and right the trees that could be saved. Volunteer arborists were involved in all stages of the Sandy recovery of the grove, making tree assessments, removals, and continuing to monitor the site over time.

What is even more unique is when we see signs of individual acts of stewardship and care that occur outside the frame of these formal events and programs. The ability to embrace these acts as healthy and productive forms of engagement, rather than intrusion into the authorities of the land manager, requires an ethos that is open to community action, voice, and power. Lisa Simms of the NJTF showed us examples of “guerrilla plantings” that occurred in the grove—people have brought bushes and flowers and are planting in the understory to complete the grove through their individual acts. Lisa pointed out the flowers that she, herself, planted from her home garden. These are examples of the public intimately engaging with the space, adopting it, and transforming it. This type of engagement, regardless of whether it deviates from the master plan, is welcome in places like this as stewards are more interested in cultivating an attachment to place rather than viewing a ‘pristine’ ecological restoration site.

* * *

Through these visits, we can see the crucial connection between the need for unplanned space, the role for community stewards, and the ability for neighborhoods (people and places) to cope with change. Thus, stewardship can be understood as a mechanism for cultivating social-ecological resilience. While there are many forms of community stewardship in community gardens, street trees, waterways, and vacant lots—we know that these living memorials are special and even sacred places. They are imbued with the memories and intentions of their creators who sought to set aside land for remembrance, healing, and community cohesion.

One issue to explore in our ongoing longitudinal research is whether this persistence and adaptability is a broad-based trend. It is entirely possible that the need for and meaning of some sites is temporary and short-lived. Thus far, our investigations have found the opposite. Instead, we found a dedicated cadre of neighbors and friends keeping vigil in a waterfront park in Queens and a forest growing across the river from the former World Trade Center site. Finally, a key question is whether and how this sense of deep attachment to place and people can be cultivated, expressed, and celebrated outside of the context of disturbance and tragedy? What can we take from the horribly singular experience of 9/11 that translates to how we care for the land and its people every day?

Lindsay K. Campbell and Erika S. Svendsen

New York City

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

Leave a Reply