In the many current discussions about how to make cities more resilient, the potential roles of citizens and urban nature are largely overlooked. There are exceptions, including Krasny and Tidball’s work on civic ecology and that of a number of people associated with the Stockholm Resilience Centre (cf. Andersson, Barthel, & Ahrné, 2007; Barthel, 2006; Bendt, Barthel, & Colding, 2013; Elmqvist et al., 2004; Ernstson, Barthel, & Andersson, 2010; Krasny & Tidball, 2012; Tidball & Krasny, 2007). However, the level of interest seems disproportionately small given the tremendous opportunities for citizens to steward nature in cities—or to ‘collaborate’ with nature, as Ernstson and colleagues have inspired me to think of it:

In order to build resilience and face uncertainty and change means to harness the interactions between stakeholders. This requires an involvement of society in its broadest sense towards a change of culture that makes ‘‘collaboration’’ between society and the environment (rather than mere ‘‘interaction’’) the central focus of attention.

—Ernstson, Leeuw, et al., 2010, p. 538

Along with citizens and nature, urban spaces are the third player in this transition waiting to happen. I share Timon McPhearson’s belief in the potential of vacant land in cities (TNOC Encore July 2014). My interest also extends to other ‘loose spaces’ (Franck & Stevens, 2007). These include areas that are not necessarily empty but are in transition, such as post-industrial sites, alleyways that are no longer used for service provision, waterways along which freight has ceased to move and even official greenspaces that do not currently meet the needs of users. I like the idea of “sustainability fallows” (a term I learned from Marianne Krasny’s contribution to TNOC’s recent roundtable on urban environmental education), which refers to all kinds of urban spaces that are lying ‘fallow’, just waiting to have their potential released and be transformed into assets.

Vacant land and undervalued urban spaces have a key role to play in helping to restore urban ecosystems to health and, as Timon also mentioned, in reconnecting people with nature. In another recent TNOC encore blog, Tim Beatley referred to the extensive evidence concerning the positive impact of contact with nature on human health and well-being. Not very long ago I undertook a literature review for The Nature Project (as background for developing strategies to combat nature deficit in Quebec) and was staggered by the range of effects that had been documented. In light of this, it was disconcerting to hear (during the empirical phase of the research) about the lack of contact with nature and the level of discomfort, and even fear of nature, experienced by many Quebecers.

It was however reassuring to discover that solutions were close at hand. We weren’t going to have to find the large amounts of money and overcome the other barriers to getting people out into the wild (which was initially seen as a possible solution to the nature deficit). The environmental educators and biodiversity experts that I interviewed confirmed that we had everything we needed to turn this trend around within the city itself. They believed that urban nature could provide the regular contact people needed to develop a relationship with nature (while also agreeing that experience of less human dominated environments was very valuable and should be available to those who sought it). Several very committed environmentalists told me about how their own dedication to the natural world began in a vacant lot near their childhood homes—and I was assured that watching pigeons was a perfectly good starting point to learn about ecosystems. What these experts also noted was the need to improve both the quality of nature in cities and the opportunities to interact with it. The ‘quality’ that was sought seemed to combine increased biodiversity (and diversity in general), eco-revelatory capacity and elements that people would find interesting and attractive.

As Timon noted, there are many spaces of opportunity in cities. The challenge is how to move them out of their ‘sustainability fallow’ phase and transform them into assets. The large number of urban spaces that need help to fulfill their social and ecological potential makes such a transformation an ambitious project.

Where can cities find the resources to enhance urban nature and maximize citizen interaction with it? Fortunately, a large part of the answer lies with the citizens themselves—and with the places. Around the world, an ever-increasing number of citizens have demonstrated their willingness to get involved in working with nature and transforming their cities.

I have experienced firsthand the level of commitment of volunteers who have struggled for years to help nature thrive in urban spaces and allow people to benefit from it. And it has been a struggle—our efforts to green schoolyards and alleyways in Montreal faced resistance from staff of local government and schools, as well as neighbors and parents. Although there were some supports in place for these sorts of initiatives, we still seemed to be going against the grain. A widespread feeling seemed to persist that nature didn’t belong in cities. Nature was troublesome, potentially dangerous and without any obvious value. If nature was present, it should be restricted to carefully controlled patches in people’s yards or parks. There was also a sense that citizens had no right to intervene in the cities where they lived. It was up to authorities to make decisions and up to paid staff to implement them. In this context, it is easier to stick to mown grass and tarmac rather than attempt creative things involving diverse species and requiring complex maintenance.

Fortunately the tide is turning. The efforts of guerrilla gardeners and insurgent urbanists (Hou, 2010) have helped people get used to wilder and more diverse urban spaces. More city dwellers have begun to realize that relinquishing a bit of control can lead to more interesting cities, greater sense of community and a generally better quality of urban life. There are still people who are uncomfortable with the idea of replacing pavement with vegetation and letting their neighbors make decisions about what should be planted, but they no longer dominate the discussion, they are part of the discussion.

Many local governments that were previously closed to citizen intervention are also becoming more open—in part because they realize they can’t look after things themselves. In the UK, budget cuts have affected maintenance of parks and public spaces for a number of years now and local governments have had to let citizens take over—and are gradually learning to work with them. Montreal now has a fantastic network of green alleyways (ruelles vertes if you are looking for more information) and its expansion is officially supported. The champ des possibles is a space transformed by citizens and now officially co-managed by citizens and city.

Sadly, I cannot speak about these advances in Montreal without also mentioning the recent bulldozing of the wonderful ‘Parc Oxygène’. This urban oasis was created by neighbors nearly two decades ago and looked after and appreciated ever since. The land is privately owned and is now slated for development and the argument was made that the cost of protecting this small space was too high. I would argue that it was an iconic space that has inspired many Montrealers to make positive changes in their neighborhoods and therefore the cost of losing it was too high. I hope that one day the worth of places that redefine a city and invite citizens to be part of making it a better place will be factored into such calculations.

How to get citizens involved with urban nature:

Invite them

How can we ‘invite’ citizens to engage with urban nature in ways that make their cities more socially and ecologically resilient? I believe such an invitation is most effectively communicated through the landscape itself.

If someone asks you to define ‘city’, chances are that an image of an urban landscape will come into your head and that will be your starting point for thinking about what a city means. For many people, that image is still one of tall buildings and expressways with barely a living thing, human or otherwise, in sight. But that is gradually changing and it will change further as there are more and more examples of urban landscapes where people and nature are highly visible and the relationship between them is one of collaboration rather than control. I use ‘collaboration’ to refer to people working with urban nature rather than against it; protecting and enhancing nature and consequently enjoying the many ecosystem services provided.

So how can we encourage ‘inviting landscapes’ to come into being? The first strategy is, of course, not to block the efforts of people who take it upon themselves to make them.

Include everybody

It is also important to think about how to deliberately design and create such landscapes, particularly in areas of cities where people do not generally feel empowered to transform their local landscapes—or even to interact with nature. Even in areas where visible changes are underway, it is important to ensure that the invitation is inclusive. It shouldn’t just speak to people who are comfortable sneaking out in the middle of the night to take a pickaxe to the pavement—or people who are neighborhood organizers or biodiversity experts. The invitation needs to make all sorts of people feel that they have permission to intervene in the spaces they live, that they are included in the process and that they have something to contribute.

In Clovenstone (Edinburgh), citizens supported by Wester Hailes Edible Estates have begun transforming a small triangle of sad looking grass into a community garden. They will retain the enclosing fence (which can make the area feel helpfully ‘defensible’) but they have also placed raised beds around the perimeter of the fence and have built a step “so that no one hurts themselves climbing over the fence”.

Make it seem safe

The landscape has to signify permission to enter—and reassure people that it is safe.

The fear of even slightly wild places in cities should not be underestimated. Numerous people involved in transforming urban spaces in Manchester have told me about what a difference a mown path makes (even through what would otherwise be viewed as weeds).

Cultivate an aesthetic of care

An ‘aesthetic of care’ (Nassauer, 1997) is very important in loose urban spaces. Most people recoil from places that are subject to neglect and victims of disdain. Removing litter is key. It needs to be repeatedly removed until a space stops being perceived as a dumping ground. Usually neighbors and particularly keen volunteers can be persuaded to do this a couple of times a year (and it should be made clear that it was citizens who did it) but this is an area where there should be investment in paid staff to sustain the invitation until people begin to take it up.

Showing that the place is cared for gradually changes its identity. There are ways to reinforce this, like giving it a new name. Soon no one in Manchester will remember that ‘Nutsford Vale’ was once known as ‘Matthew’s Lane Tip’.

Make identity apparent

Make identity apparent

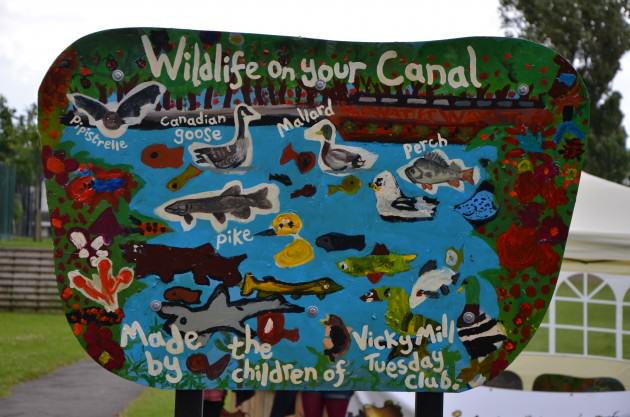

The identity of a place is important for inviting interest and much of the vacant land in cities seems to have no inscribed meaning or story. Most places do have some sort of little known story and a bit of research might reveal what it is and then efforts can be made to make it legible in the landscape. Or new stories can be created by organizing activities in the space or installing something that attracts attention. Interesting and attractive elements can be added; wildflowers seem to work particularly well. One can look for ways to make the nature that is present more legible. If it can’t be seen, show what is hidden or what could be there.

Support the unexpected

Surprises are generally a good idea. Not every Inviting Landscape needs to be surprising but people need something to help change their ideas about what they can do in urban spaces. City centers are good locations for the unexpected because lots of people pass through them and because they send the message that if you can do something in places where nature is so little visible and space so controlled by powerful entities, then you can do it anywhere.

What regeneration of the canal landscape could look like? (The backdrop is a photo of the sort of regeneration that is going on just behind this greener space created in the corner of a car park in Manchester.)

Show that cities can change

Cities have a way of seeming very permanent and we tend to think that what we see is how things should be and how they will stay. Cities often communicate obduracy (Hommels, 2005); the scale and concreteness of much urban infrastructure makes the city seem resistant to change. This is ironic because cities change all the time and the magnitude of things can just as easily be taken as evidence for what is possible, as Raymond Williams once noted:

H. G. Wells once said, coming out of a political meeting where they had been discussing social change, that this great towering city was a measure of the obstacle, of how much must be moved if there was to be any change. I have known this feeling, looking up at great buildings that are the centres of power, but I find I do not say ‘There is your city, your great bourgeois monument, your towering structure of this still precarious civilisation’ or I do not only say that; I say also ‘This is what men have built, so often magnificently, and is not everything then possible?’ (Williams, 1975, p. 15)

Changes can be temporary. They can provide examples of what could happen when people are not quite ready for it on a more permanent basis. Or they can occupy spaces that are slated for other uses and thus send a message that things don’t have to be permanent. ‘Meanwhile land’ can serve all sorts of purposes and show that urban spaces can be adaptable to changing needs and possibilities.

Focus on home-like landscapes

While city centers represent excellent locations to showcase possibilities, their often more ‘official’ and commercial landscapes are not the ones with the most potential to extend an invitation. People are more likely to intervene in landscapes that feel like home, places which are human-scale and defensible and where they run into people they know. That is why alleyways and sidewalks in residential neighborhoods are generally quite inviting. These are places that feel like they are in between public and private space regardless of who actually owns the land. Because of proximity to where they live, people have opportunities for regular interaction with these landscapes and with the other people who use them, which helps to build connection, a precursor to action

Opportunities to interact with other people are hugely important. People attract people, and out of simple exchanges come great ideas and transformative projects. Putting in a place to sit and organizing gatherings creates space for things to happen.

Make it personal

It is good when the things that happen are clearly a result of citizen action. Hand-painted signs and unconventional infrastructure send a message that these things were done by people like oneself.

Better still if one can actually see the citizens. People are part of landscapes too and nothing is a more convincing message about the capacity of citizens to work with urban nature than seeing us doing it. If a passerby shows interest, say hello and explain what you’re doing. Tell them they’re welcome to get involved in some way if they like.

One of the most important characteristics of an Inviting Landscape is that it must appear that good things are being accomplished but still seem unfinished in some way. It should look as if it’s waiting for someone else to come along with their particular skills and ideas to do the next bit. This is challenging for changemakers. Most people, including urban planners, landscape architects and citizen activists, tend to think in terms of finished projects—and then worry about maintaining them.

But just as we have begun to speak about resilience as a goal for cities, in recognition of inherent complexity and constant cycles of change, so we should think in terms of resilient citizen engagement. People should constantly be invited to bring their own vision and energy to some part of a transformative project or to the next step. Rather than getting depressed about how we’re left with just a few volunteers and the garden isn’t being weeded, we can think about how to create an invitation for other citizens to come and work with nature in their own ways.

Janice Astbury

Edinburgh

References:

Hommels, A. (2005). Unbuilding Cities: Obduracy in Urban Sociotechnical Change. MIT Press.

Tidball, K., & Krasny, M. (2007). From risk to resilience: What role for community greening and civic ecology in cities. In A. Wals (Ed.), Social learning towards a more sustainable world (pp. 149–164). Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Great piece, Janice. Sustained citizen engagement at the nature-culture nexus is indeed key. To quote Leonie Sandercook: Utopia is a construction site.

A very welcome article. I am particularly interested in the idea that observing pigeons is a way of engaging children’s interest in other species. The widespread extirpation of urban species regarded as ‘pests’ undermines the opportunity to encourage the appreciation and love of of the ‘common’ rather than the distant and exotic.