Brazilian landscapes suffer rapid and repetitive transformations through intense and successive periods of exploitation—for example, the Brazilwood that gave the country its name, sugar cane, coffee, cattle, soy or urbanization and its infrastructural needs. Such degradation processes provoke losses of nature and biodiversity, which are hardly reversible, but restoration initiatives had already been introduced and occur in rural and urban landscapes at the intersection of landscape architecture, landscape planning, landscape ecology and ecological restoration.

The Rio 2016 Olympic Park, on the city’s waterfront, is converting its degraded landfill into an ecological restoration project. This is not an isolated initiative but is part of a larger ecological and landscape strategy for lagoon borders and ecological corridors for the city of Rio de Janeiro.

EMBYÁ Paisagens & Ecossistemas landscape studio was commissioned to detail and pursue AECOM’s preliminary landscape architectural study for the Olympic path and the park at the lagoon’s edge. The project for the border of the lagoon had evolved from the preliminary study, due to the environmental requirements of creating an ecological restoration.

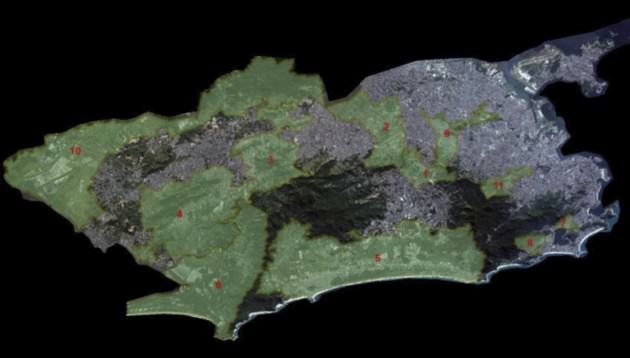

The Rio 2016 Olympic Park is inserted in the Macro Watershed of the Jacarepaguá district (commonly called Barra da Tijuca) and planned in 1969 by Lucio Costa, who was also an urban planner who worked on the city of Brasilia. The district’s composition is influenced by rational urbanism, its traffic structures are bold and its uses observe monofunctional zoning categories.

Lucio Costa’s plan has suffered social transformations since its design and, as a result of market pressure, has been transformed into a district of gated communities punctuated by commercial structures that mostly have a “Miami” residential identity. In forty years it has been transformed from a human desert that only had only beaches, swamps, sand dunes, shrubs and thickets, into a district with more than 300,000 inhabitants, a second urban center for Rio.

The macro watershed of Jacarepaguá is framed on its northeast and northwest sides by two ranges of forested hills, two of the biggest urban conservation units in the world (Parque da Pedra Branca and Parque da Tijuca) and on its south shore by 27 kilometers of ocean beaches, making a triangle of sandy lowlands. The name of this landscape type is restingas, which are wide sand deposits running parallel to the shoreline. These deposits were produced by sedimentation processes in two separate historic sea level rise incidents 120,000 and 5,000 years ago. These geologic formations give their name to the area’s specific marine-influenced vegetation that colonizes its soils through different phytophysionomies from reptant beach vegetation, shrubs, thickets, floodplain forest, and fresh and saltwater swamps. These formations are very fragile and quickly react to any transformation or pressure. These ecosystems are currently suffering from anthropic pressure in a direct conflict with the removal of the land cover due to land-filled urbanization and its consequent dramatic changes in landscape dynamics.

This geology created by a rise in sea level is very sensitive to the actual return of this phenomenon, the most sensitive areas are the humid zones and water bodies like lagoons and swamps, which will follow the sea level rise elevation and will extend their surface, and lowlands that will turn back into swamps. Lagoons and humid zones are connected to the sea level by channels or by marine pressure on the water table. But as the frequency of extreme climatic events increases in Rio de Janeiro, its inhabitants are already able to testify to the collapse of its hydrologic system due to massive flooding. In addition to another natural factor, it can dramatically influence the magnitude of flooding caused by rain in combination with sea tides, during a full or new moon or during high tide (or both at the same time). It often results in the entire city coming to a standstill, affecting road infrastructures and other lowland typologies like residential and commercial areas.

Ecological restoration and the reconstitution of a continuous planted bank of mangrove is not only important for the wildlife habitat but is also a tactical tool for stabilizing the edges of the lagoon. The mangrove’s dense terrestrial and aerial root system prevents erosion and acts as a resilient agent in the changes of the lagoon limits.

The main problem for these lagoons is their environmental suffering, which is mainly due to biological and chemical pollution on top of abundant sedimentation, which is creating great oxygenation problems for its water bodies.

Regulatory instruments for territorial occupation are numerous and Brazil has a wide range of environmental laws applying to its territory. Brazil is a federation, so these laws are issued on three levels: municipal, state and federal, creating a dense legal context for any territorial intervention. The Código Florestal is the main legal environmental instrument, issued from the federal level, it applies to all Brazilian territory. Its terms define the Permanent Preservation Areas (APP), which are unoccupiable areas defined by geomorphologic, hydrologic and vegetational criteria, which are environmental conditions for land use. The Jacaperaguá Lagoon, in front of the Rio 2016 Olympic Park, has a 25-meter-wide, georeferenced marginal protection strip that is defined as an APP bordering its entire lagoon front.

Although still in the planning phase, Rio de Janeiro has an ambitious mosaic of green corridors crossing the city. The mosaic needs to be implemented, considering the speed with which urbanization is occurring. One of its many sectors is the lowland area of Barra da Tijuca, which is different from most of the other regions, as mainly the hills receive this kind of intervention. The sector of Barra da Tijuca, however, which is also called the Olympic Corridor, was already planned by EMBYÁ in a multidisciplinary working group in 2013. The goal was to identify the lowest-lying land as a potential area for ecological connections and for urban ecology initiatives, as they can also assume social functions.

Barra da Tijuca has already had restoration interventions, which were all done by the landscape architect Fernando Chacel during the 1990s, when he built them and created the Ecogenêse methodology. This involved working with botanists, biologists and naturalists to recreate natural landscapes that imitate natural local vegetal formations through the use of restinga native plants like bromeliads, shrubs, trees and mangroves, which are another coastal ecosystem at the intersection of salt and fresh water.

Ecological restoration and native vegetation planting is a legal exigency for these water body borders, but the legal texts remain quite undefined with regard to methodologies, phytophysionomies and biodiversity, etc. These areas are commonly planted with an arboreous stratus in conventional reforestation methods and alternating monospecific bush masses.

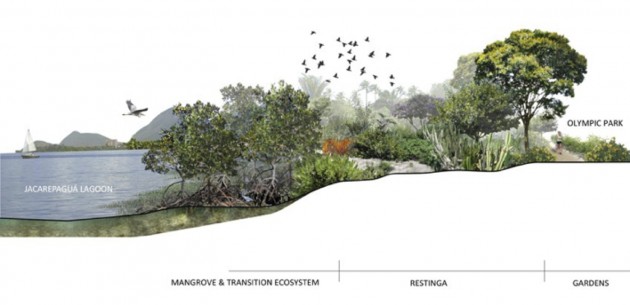

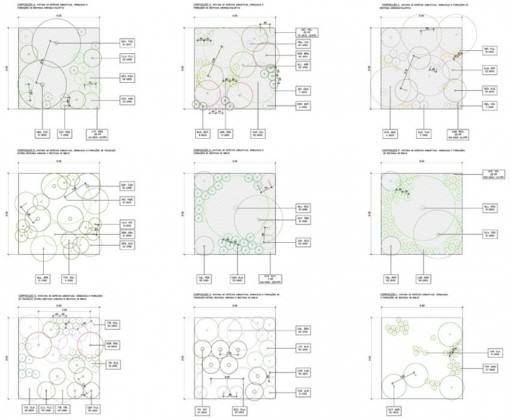

The ecological restoration for Rio 2016 defines the use of two main ecosystems based on scientific floral studies made prior to occupation: manguezal and restinga. In the case of the restinga, the study did not only focus on the arboreous layer but also on reconstructing the mixed-stratus vegetation communities.

Before work on the Olympic Games site began, it was a speedway with an aerodrome on its border and irregular occupations from different social classes. Its topographic morphology is characterized by flat land that has been filled with earthworks according to the occupation methodology of the region, which has resulted in few areas for the natural accommodation of rain water and increased flood management problems. The vegetation used was mainly exotic herbaceous, including a few exotic trees. In addition to its flat landfill typology, it is configured as an artificial landscape, with no natural attributes to preserve.

Restinga and mangrove phytophysionomies respond to topographic conditions, and can change their structure within a few decimeters of level variations. The mangrove, which remains permanently in brackish water, requires the removal of the emerged part of a landfill and proportionally pushes itself into the lagoon to create a submersed plateau. During the planting phase this vegetation is sensitive to water level variation, but after growing higher than one meter it becomes resistant to big changes in water level, and when it is mature can cope with drastic changes. Another factor for mangrove planting that is necessary in the Jacarepagua Lagoon is protection from floating garbage, and a system to alleviate this problem must be installed in the water on the border of the submersed plateau.

From sandy lowlands to humid zone, render of the project, EMBYÁ

Mangrove trees or seeds are not sold in nurseries and for every mangrove restoration it is necessary to make an on-site nursery with seeds or cuttings, depending on the species collected in the same watershed. As mangrove is a pioneer ecosystem, this operation is easy, with high rates of success. This process will only take three months if carried out at an appropriate moment regarding the seeding periods. Two species of mangrove were planted in parallel strips, Laguncularia racemosa and at a greater width Rhizophora mangle, as its root system permits more visibility of the lagoon for visitors.

The listing of restinga species was based on phytosociological studies made of the vegetal communities, and based on their observations 8 mixes of plants were created according to different vegetal strati, such as reptant, herbaceous, cactaceous, shrubby, arboreous and sparse native vegetation to create a biologically diverse restoration that better reflects the ecological structures of the restinga than in a conventional reforestation project that only uses an arboreous vegetation stratus.

Similarly to mangrove vegetation, a part of this restinga vegetation needs to be produced, as specialized nurseries are very rare and are relatively small. Collecting seeds will need to be done in other restingas in the state of Rio de Janeiro, as in the Barra conserved areas are very rare and their floral components have already been greatly disturbed.

Irrigation is being done manually during a three-month period, which is enough time to get the plants’ root systems developed in their new soils. Maintenance will be carried out for two years, and mainly consists of removing invasive species.

This contemporary chapter of ecological restoration in Barra da Tijuca is planned and projected to connect with other similar restoration projects, as each land owner bordering the lagoons and water bodies needs to restore it. Some rare interventions make the completion of corridors more rapid: environmental compensatory measures financed by polluting firms like steel mills and oil extraction companies, etc. These companies were involved in detailing planning of the ecological corridors, for instance the western part of the Olympic corridor that connects lagoons, canals, hills and beaches.

This also included a citizen participation process. Planning and constructing regenerated natural spaces requires extended knowledge of environmental legislation, urban legislation, biology, sociology and engineering. Landscape architecture provides the tools and the methodology for this kind of work.

Brazil is actually the most biologically diverse country on earth and the formation and recognition of the landscape architecture diploma is in the process of regulation. This biodiversity can serve as a special highlight for the future of the profession and for the overall formation of Brazilian landscape architecture.

Pierre-André Martin

Rio de Janeiro

Leave a Reply