“Civilisation; it’s all about knives and forks.” —David Byrne

As a child I was not nature-deprived. I lived in small towns and villages in rural Somerset in England, and enjoyed nature study in primary school but I know that I’ve never seen or experienced anything truly wild. I never will, and as a civilised ape I’m really grateful for that.

Left to our own devices most of us couldn’t survive in the wilderness, not even in what passes for wilderness in its degraded form. Yet we need the wild, we evolved there, and as we can’t experience it for real anymore we make do with controlled, vicarious ‘wildness’, most of which involves getting scared in some way—roller-coasters, horror movies, going face-to-face with tigers in a zoo…

For those with nihilistic tendencies it isn’t hard to argue that there is no longer any such thing as wilderness. If you define wilderness as natural environment untainted by human intervention and manipulation, then there isn’t any because the damaging reach of industrial civilisation is literally global—DDT contaminates Antarctic penguins and the PCB contamination of oceanic particulate matter in Antarctic waters is similar to the level of contamination in the North Sea .

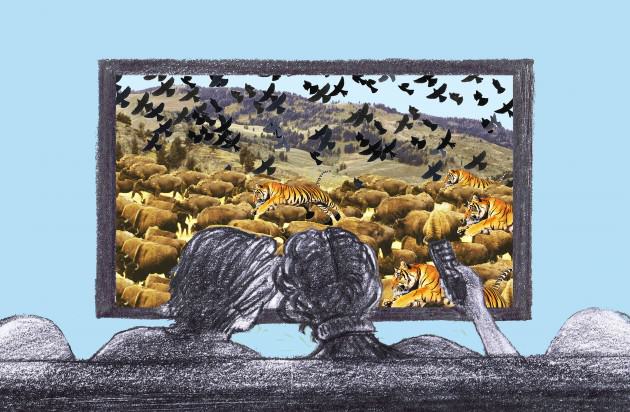

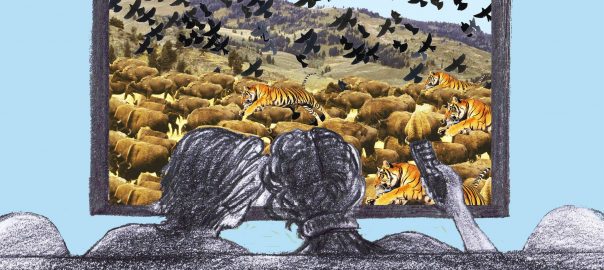

Real forests are wild. They are places where one can both be lost and wish to escape from. But are ‘urban forests’ truly wild? For all the talk of ‘wild’, the wildlife experience is no longer defined by lived experience, because the definition of ‘wild’ has escaped into the thickets of a wholly urban civilisation. ‘Wild’ is behind bars, ‘wild’ is on a screen, ‘wild’ is not something that most of the human race ever experiences any more. ‘Wild’ is vicarious. It’s seductive and dangerous—but not in the way that wild used to be, it’s dangerous because it’s encapsulated. Packaged in media. Mediated by packaging. The danger is in mistaking this domesticated product for authentic experience. Its teeth have been taken out, its claws are manicured and its hooves are muffled. The roar of the wild has been reduced to whatever you’ve set the volume control to on the remote.

If a million people can see a buffalo on TV, why would you need a million buffalo?

Not enough animals in the frame? Photoshop a few more to fill up the space.

Virtual reality is rapidly becoming more interesting than reality—it already is for many. The landscapes in Avatar may have some passing resemblance to Earthly places, but they are much more fantastical. Much more fun to look at.

We’re clever creatures. Thanks to computer-generated imagery even the most run-of-the-mill children’s animated feature movie can contain astonishingly convincing pictures of landscapes, plants and creatures. Imaginary landscapes have become routinely realistic, and for that we have to thank Benoit Mandelbrot and his discovery that the apparent disorder of chaos can be mathematically described by the sublime patterns of fractals. He sought a way to define the geometry of trees and clouds and was successful. Now filmmakers can build mountains and fly clouds that are mathematically correct and we find ourselves unable to avoid falling for what is, after all, a scientifically sound illusion of authenticity.

We’re clever creatures. Thanks to computer-generated imagery even the most run-of-the-mill children’s animated feature movie can contain astonishingly convincing pictures of landscapes, plants and creatures. Imaginary landscapes have become routinely realistic, and for that we have to thank Benoit Mandelbrot and his discovery that the apparent disorder of chaos can be mathematically described by the sublime patterns of fractals. He sought a way to define the geometry of trees and clouds and was successful. Now filmmakers can build mountains and fly clouds that are mathematically correct and we find ourselves unable to avoid falling for what is, after all, a scientifically sound illusion of authenticity.

![]() These experiences are literally unreal, and whilst they may teach us something about nature’s fractals, they also disconnect us from the real world.

These experiences are literally unreal, and whilst they may teach us something about nature’s fractals, they also disconnect us from the real world.

Moving and shaking

At the scale of the planet, the disconnect between humans and the natural world is becoming more complete (and complex) by the day. Which is to say that if we fail to treat the biosphere’s natural processes with respect then those processes won’t ‘respect’ we humans. Our disruption of ecosystems is profound and getting worse, but we don’t really know what we’re doing. We can measure the increasing pollution of the atmosphere and track some of the changes in global systems that result, we can make an informed estimate of the number of invertebrates in the world compared with 40 years ago and establish that the population has almost halved, and we can pretty much count how many trees and fish we haven’t got compared with, say, 50 years ago.

We can point to all this data and tell corporate leaders, politicians and decision-makers ‘hey! something’s happening here!’ but it means diddley-squat to most of them. Every day the world news services and financial gurus are exalted or depressed by a point or two shifting on the Dow Jones, the FTSE or the Hang Seng. Every day, these measures of economic health can trigger excited speculation on global progress towards either boom or bust or nothing much. Meanwhile, the inexorable decline of every indicator that describes the state of the natural world goes without comment because it doesn’t mean anything to most of the movers, shakers and commentators of sound-bite capitalism.

At the scale of the city, the disconnect is at its worst. Apart from the wind, rain, snow and smoggy sunlight that might still have a directly experiential effect on their daily lives, most urban dwellers have no idea what ‘nature’ is. When nature is given acknowledgement in the media that acts as the average citizen’s eyes and ears to the world, it’s invariably sensationalistic—floods, blizzards and heat-waves make the headlines. Nature looms up as something to fear and therefore something to control, to put back in its box, tidy up and get out of the way.

But at the scale of the city we can make a difference. At the scale of the city we can design for connection of daily life with the rhythms of the planet. Although they might not produce true wildness (or wilderness) we can include urban forests and woodlands, street trees, parks and reserves to the mix of place and experience for all citizens. As many writers for TNOC have explained—most recently Janice Astbury in TNOC 7 September 2014—there are many small ways to bring nature into the city and, crucially, bring people into the making of that nature. All of this is important, but there is a problem with the big picture; it’s a problem that runs deep in modern culture: it is modern culture, or, more precisely, the culture of modernism.

Modernism, greenery and the dark arts

Yet the legacy of modernism is mostly one of liberation. Modernism freed us from the shackles of stale thought and feudal relationships. It promised a new, more efficient society in which form followed function rather than moribund fashion and it tried to articulate a cultural framework that was simultaneously progressive and egalitarian.

But like all kinds of revolutionism it had trouble distinguishing babies from bathwater and its followers tended to distill subtle ideas into slogans and often seemed to get the wrong end of the stick. Whereas progressive modernist architects like the inimitable Frank Lloyd Wright laid stress on working with nature to shape, inform and become integrated with architecture others, particularly those in the thrall of Le Corbusier’s ideology, saw beauty and purpose in the machine regardless of context. For the many modernists and neo-modernists who carry the flame of Le Corbusier’s aesthetic dogma, nature remains something to be trammelled and tamed, something to be denatured; and the city is their canvas and playground.

But like all kinds of revolutionism it had trouble distinguishing babies from bathwater and its followers tended to distill subtle ideas into slogans and often seemed to get the wrong end of the stick. Whereas progressive modernist architects like the inimitable Frank Lloyd Wright laid stress on working with nature to shape, inform and become integrated with architecture others, particularly those in the thrall of Le Corbusier’s ideology, saw beauty and purpose in the machine regardless of context. For the many modernists and neo-modernists who carry the flame of Le Corbusier’s aesthetic dogma, nature remains something to be trammelled and tamed, something to be denatured; and the city is their canvas and playground.

The penchant of the modern modernist for covering buildings with greenery can be understood once you realise that the greenery they favour has been reduced to a product, delivered in industrially produced, neatly stackable plastic boxes. The gorgeous walls of manicured plant life that are now beginning to show as bold new brush strokes on the urban canvas present a beautiful illusion of nature in the city, but they are as far from ‘wild’ (and just as aesthetically precious) as the brutalist concrete that was the contemporary modernist fashion a short few decades ago.

Don’t get me wrong; green walls are wonderful and I’m an advocate for them and for green roofs, but bringing nature into the city has to run deeper. It has to engage people in ways that are not entirely predictable or a result of following maintenance manuals for vertical gardening planters (e.g., the roof garden I designed at Christie Walk was installed and is truly ‘gardened’ by the residents).

But cities demand a lot of command and control. They are the antithesis of wildness. Regimentation and regulation is second nature to city-making. The great adventure of civilisation was all to do with making human settlement stay in one place. Once you no longer move on when the seasons change or the water dries up or the food runs out or the excrement piles too high, you have to get organised in very particular ways. The dark arts of accountancy and bureaucracy are needed to measure out and distribute resources, allocate activities, keep track of individuals and avoid disorder. In order to protect the accrued grains, brains and wealth of the settlement, standing armies have to replace roving warriors. Farmers replace hunters and gatherers; gardeners and maintenance crews learn the discipline of eternal vigilance against the incursion of weeds—those persistent front-line troops of the unfettered wildness that continually threaten to reclaim the city in the manner quite accurately portrayed in ‘I Am Legend’.

Readers of this blog would all most likely agree that a meaningful connection with nature is vital to human well-being but is that something that cities can really deliver? Parklands and green public spaces do introduce something of that connection—wildflower meadows more than manicured lawns, perhaps—but a prohibition against too many people stepping on the grass becomes an essential part of the management strategy when population numbers and density begin to rise. The scale of the city is key.

Readers of this blog would all most likely agree that a meaningful connection with nature is vital to human well-being but is that something that cities can really deliver? Parklands and green public spaces do introduce something of that connection—wildflower meadows more than manicured lawns, perhaps—but a prohibition against too many people stepping on the grass becomes an essential part of the management strategy when population numbers and density begin to rise. The scale of the city is key.

Small is…wilder?

The historical city was much, much smaller than what we call cities today. Until fossil fuelishness blew them open and drove the machines that tried to kill them, most cities were, by today’s standards, and in all cultures, tiny. The biggest cities were then, as now, the centres of empires, in Medieval times cities like Baghdad and Beijing were the world’s largest with populations of just one million. Most cities held populations of only tens of thousands, they were dependent on somatically powered transport and could be traversed in little more than 15-20 minutes. Rather than sprawling suburbs, they were ringed closely by agricultural land woven into a matrix with whatever landscape was indigenous to the region. The city was set within a framework of nature that would have been obvious to all of its inhabitants, not in a consciously aesthetic way but simply as a fact of life.

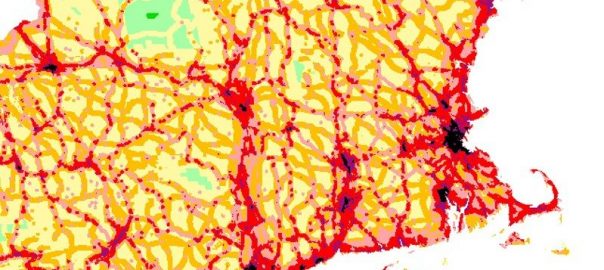

The modern reality is that the pre-industrial framework and setting has been reversed and nature, such as it is, often in a remnant or degraded form, is contained by cities and, by extension, their industrial landscapes. Enabling people to connect with nature is no longer about reaching out to nature but creating facsimiles of natural environments within urban systems that people can somehow reach into. Plunging desk-bound hands into soil can take place at the scale of a balcony flowerpot or a community garden. That the fuzzy-edged messiness of community gardens shows a tolerance for trial and error is part of their beauty. But can the city ever really embrace the wild?

Regardless of the inverted morphology of the modern city-nature relationship, the key to any engagement by citizens with nature is distance. Wherever and however they live, any connection with nature should take place within a 5 to 10 minute walk. This was the distance from old city centres to their nature-girdled periphery and anything further becomes a journey rather than a stroll. There’s something ‘natural’ about it. In the pre-industrial past, it wasn’t much further to where the wild things were. I’ve written before (here and here) about George Monbiot’s lucid proposal for rewilding—giving nature the opportunity to restore landscapes by letting them evolve without the prejudices of human culture (TNOC, 21 August 2013).

Any attempts to free nature from the city run the risk of further alienating citizens from nature. Making cities compact and small so that they are embedded in nature, rather than vice versa, offers a strategy of sorts for enabling the return of the wild, but its realisation would be more than a little challenging at this stage of our evolutionary trajectory. Placing cities within sealed or semi-sealed structures such as giant domes (like Bucky Fuller’s proposal for Manhattan) might conceivably allow nature to be wilder, thriving outside the city limits, but that much separation of the city from nature has its own peculiar dangers.

One thinks of the denizens of the Domed City in the 1976 movie version of ‘Logan’s Run’ who believed the ‘outside world’ to be barren and poisonous. For many city dwellers today the wilderness is already almost that alien and threatening. We need our children to grow up around natural history so that nature is not seen as alien or as Jennifer Frazer wrote “When kids do not grow up around natural history, they become adults who are not only ignorant of natural history, but who do not care about nature and view it as disposable and unimportant.”

“You need a mess of help to stand alone.”

—Brian Wilson & Jack Rieley

The city is a collective creation. It can only exist because of a high level of co-operation between individuals. It requires society—as does that most basic unit of human organisation, the tribe. (Families don’t require society in the same way, they arise as an emergent characteristic from the demands of procreation and give few, if any, pointers as to how to organise collective effort.) The idea that individuals are, or should be, at constant war with one another in a battle for survival simply doesn’t fit the observed reality of civilisation and its evolution from tribal roots. The scale of co-operation has grown rather than diminished. Published in 1902, Kropotkin’s ‘Mutual Aid’ made an early and eloquent claim for the inherently tribal, rather than familial, nature of human society and its imperative to favour co-operative behaviour rather than the ‘red in tooth and claw’ interpretation of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

That view was avidly promoted in support of laissez-fair Victorian capitalism by Thomas Huxley, in a kind of late 19th century precursor of late British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s nihilistic assertion that ‘there is no such thing as society’. She might as well have said ‘we don’t need cities’, but that’s another political assertion that doesn’t bear analysis. Even as the craggiest, most individualistic survivalist packs his trunk with AK-47s and BPA-free cans of baked beans and powers off into the mountains in his military-surplus Hummer, he remains tied to the wheels of civilisation with umbilical cords of dependency that tangle their way through great, heaving masses of industrial infrastructure. None of that infrastructure would exist but for the invention of the city. The survivalist could not begin to reach the wilderness without a city to take him there.

Paul Downton

Adelaide

Leave a Reply