In 2010, the 193 national governments that were then party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted a decision to endorse the “Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020”—to guide their actions towards stemming the biodiversity crisis over the following 10 years. Within the Strategic Plan are contained 20 specific “Aichi Biodiversity Targets”, dealing with each area that requires attention in order to achieve the original objectives of the Convention: the conservation of biological diversity; the sustainable use of the components of biological diversity; and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources. The Strategic Plan has become well known now and forms the basis of much of the reporting and planning conducted by the Parties.

The same meeting that produced the Strategic Plan also produced a decision endorsing a “Plan of Action on Subnational Governments, Cities and Other Local Authorities for Biodiversity (2011-2020)”. This Plan of Action outlines ways in which national governments can support their local and subnational counterparts’ contributions to achieving the goals and targets of the Strategic Plan.

Despite mirroring the Strategic Plan, however, ongoing efforts are required to build awareness of the Plan of Action’s importance in achieving it. At the same time, every single one of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets relies at least partly on cities for its achievement. The fact is that cities contain the majority of the world’s population; are responsible for a disproportionate majority of its production and consumption; are growing at an unprecedented rate in terms of population and area. So the targets the Parties are pursuing at the national level rely on the contribution and cooperation of the world’s cities and citizens.

Here follows a target-by-target account of why cities are so relevant to the targets, and why Parties cannot afford to leave them out of their pursuit of their achievement.

Strategic goal A: Address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss by mainstreaming biodiversity across government and society

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”

Awareness-raising is perhaps the most basic requirement underpinning all of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, and cities are where most of the audience resides. That goes especially for the more empowered audience, including government of all levels and corporations. Cities are where the vast majority of knowledge institutions and other mechanisms for communicating the biodiversity message are found. Nowhere else can the message more easily be delivered en masse, and nowhere else is its en masse delivery more important.

Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

This Target alludes to the role of local government, perhaps in recognition of the fact that development and poverty eradication strategies are largely implemented by local authorities. It also alludes to the valuation of biodiversity. Valuation is pertinent to cities because more accurate, and therefore more useful, valuation data can be produced at the local level; and because cities, which to some appear so separate to nature, in fact contain more people dependent on it than the rest of the planet’s population combined.

Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.”

Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.”

City governments, to varying degrees depending on their context, have powers to introduce incentives or remove disincentives to benefit biodiversity. For example, in South Africa, eThekwini Municipality’s Environmental Management Department has worked with the municipal Treasury Department to develop a rating policy to remove disincentives to retain vacant, conservation-worthy land. Consider the potential of multiplying local efforts by the number of local governments (eight metropolitan, 44 district and 226 local municipalities in the case of South Africa) in any given country.

Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

Cities, due to their relatively high concentrations of wealth and despite their efficiencies and potential for greater efficiency, are responsible for about three quarters of the world’s consumption of resources (Global Initiative for Resource Efficient Cities). Only 600 cities are responsible for more than half of the global GDP (Urban world: Mapping the economic power of cities). Cities therefore offer profound potential for positive impact if their citizens make the right choices.

Strategic goal B: Reduce the direct pressures on biodiversity and promote sustainable use

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

This is one of several targets that are relevant to cities because of statistics such as those introduced under Target 4. While supply “happens” mostly in the hinterland, it is of course driven by demand. Demand for most of the world’s resources comes ultimately from cities. Furthermore, cities are also the conduits through which resources, such as tropical timber, pass before being distributed and therefore have opportunities for control of, for example, illegal harvesting of timber.

Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Cities may not be where commercial fishing happens (although in many cases coastal waters are under their jurisdiction), but they are where most if its products are consumed or the point from where they are distributed. Harking again back to Target 1, awareness-raising to guide choice of the products of less ecologically problematic fisheries also finds its most effective delivery in cities.

Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Cities are the main centers of demand for the products of agriculture, aquaculture and forestry, and the places where the public can most efficiently be rallied to support more sustainable practices through their purchases. Meanwhile urban and peri-urban agriculture, although insignificant in terms of agricultural production in most cities, has a profound effect on society in some. In Havana, for example (FAO), 89 000 backyards and 5 100 plots of less than 800m2 are used by families in the city to grow fruit, vegetables and condiments and to raise small animals, for household consumption, thereby supporting citizens while sparing the hinterland from a degree of agricultural expansion and saving on emissions from transport.

Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity.

Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity.

Large-scale mining aside, pollution control is an area where cities can clearly claim a critical role due to the proportion of industry located within their borders. Furthermore, city administrations often have the power to curb pollution through fines and taxes to limit or prohibit it.

Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.

Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.

Through ports and airports cities are, naturally, entry points for exotic species. While exotic species are needed for various reasons, their uncontrolled introduction poses a risk to native biodiversity because their effect on a new environment cannot be known until it is at a relatively advanced stage. By that time control may be futile or very difficult. In stark contrast to the vibrant ethnic diversity that is created through the arrival of people from diverse groups, individual exotic species have repeatedly proven to reduce the overall diversity of species and ecosystems. City governments have a role to play, for example in choosing native plant species over exotics in urban landscaping, and guiding the choice of species by the public for purchase.

Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning.

Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning.

Besides their disproportionate levels of consumption and production, cities are home to a large proportion of the industries that produce greenhouse gasses, which affect ecosystems globally. Cars alone are responsible for 30% of emissions in the USA (www.ucsusa.org), mostly in cities, and like all emissions these are not isolated in their impact but contribute to the global effects of climate change.

Strategic goal C: Improve the status of biodiversity by safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic diversity

Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

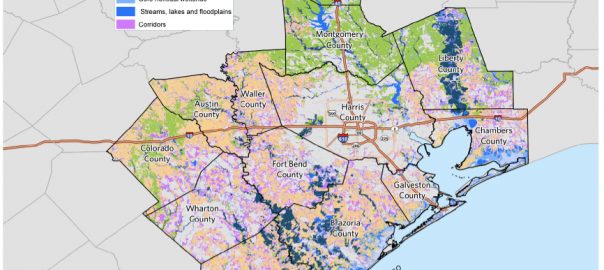

Ecological connectivity is important at various scales. A city represents a barrier to the dispersal of native fauna and flora, but green areas within the city can help. Within or surrounding cities, green areas are often protected under municipal or other levels of government, and are the protected areas with the greatest potential for access by, benefits for, and awareness of, the world’s citizens. If all cities and other local governments were to target the same percentage of protected areas as the Strategic Plan, Parties work on Target 11 would be done for them.

Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

It is a fairly well-publicized fact that concentrations of people – as expressed most typically by cities – correspond with concentrations of species and of “biodiversity hotspots, where these high concentrations of species are under especially high risk due to biodiversity loss so far. Preventing or limiting the extinction crisis that has been underway for the past several decades is therefore unlikely to be possible without the help of cities

Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.

Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.

Apart from being the greatest source of demand for agricultural products, cities often house repositories for genetic diversity at agricultural research institutions. It is also at universities and other such institutions, the vast majority of which are located in cities, that agricultural biodiversity is studied.

Strategic goal D: Enhance the benefits to all from biodiversity and ecosystem services

Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable.

Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable.

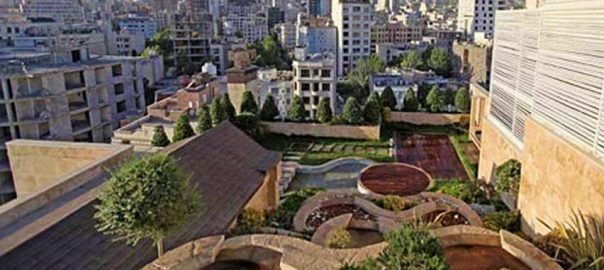

Cities are reliant on the services and goods supplied by ecosystems outside their boundaries, such as water purification by vegetated catchment areas and the production and health of the soil that supply their crops. There are also services that are provided by ecosystems and biodiversity within cities. Street trees and parks, for example, provide a cooling of the city heat island effect, as well as an opportunity for recreation and relaxation. These services are provided on a very intensive basis due to the phenomenally dense concentrations of people found in cities. By following the embryonic but growing trend toward considering biodiversity and ecosystems as green infrastructure, cities can contribute enormously to supporting ecosystem services.

Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification.

Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification.

Cities typically have a greater than average amount of resources available for ecosystem restoration, which can be more efficiently and effectively achieved in the space-intensive city environment. It is also often in cities that the effects of climate change is most severe, especially at the coast. This is partly because of the dense concentrations of people they house, but also because ecosystem services are generally eroded in and around them, making them more vulnerable.

Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation.

Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation.

Although city governments are not party to the Nagoya Protocol, its principals apply to cities and citizens. This may, therefore, be a relevant place to point out that cities are home to most of the political votes in the world. An informed society means informed political choices in democratic countries – not only at the local but also the national level.

Strategic goal E: Enhance implementation through participatory planning, knowledge management and capacity building

Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

National biodiversity strategies and action plans are, almost by definition, broad brush strokes that require replication and application at the appropriate scale on the ground. That is where local biodiversity strategies and action plans come in, translating the expansive strategies at national level into locally-relevant actions. Increasingly, national governments are acting on this realization and promoting the formulation of local biodiversity strategies and action plans by cities and other subnational governments, and consulting local government in the formulation of national strategies and action plans.

Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

A little-known fact is that the majority of indigenous and local communities reside, not in the natural environments with which they are typically associated but, in cities. Thus, Target 18 needs to consider reaching not only rural indigenous and local communities, but also city-dwellers, especially considering that it is in cities that these communities are most separated from the environments that have formed such an integral part of their cultures.

Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied.

Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied.

The majority of universities and other research institutions are located, or at least headquartered, in cities. While field work must be conducted in the field, and collaboration is often conducted through remote communication like email, learning institutions themselves are a feature of cities, and cities a feature of these institutions. In the case of some, like museums and botanical gardens, this location is not only a result of convenience, but necessity because they rely on public patronage through visits and exposure.

Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

As with protected areas, cities are (sometimes relatively well-funded) microcosms of their countries. Resource mobilization for biodiversity work is often solely dependent on the city itself, and their collective contribution to conservation nationally and worldwide is significant. In other cases cities may rely on support from national government or other avenues. In either case, whatever biodiversity work they conduct with that support, is a contribution to their country’s achievement of the Strategic Plan.

***

While there is some way to go in matching the importance attached to the Strategic Plan with that of the Plan of Action, the Parties to the CBD are increasingly demonstrating their recognition of the contribution to be made by cities. Three consecutive decisions at the meetings of the Conference of the Parties to the CBD have centered on this subject, with a fourth for consideration this year. An increasing number of examples of collaboration between Parties and cities or subnational governments is an additional positive sign. In response to COP decisions, Parties have reported on their collaboration; an increasing number of national biodiversity strategies and actions plans feature explicit recognition or inclusion of cities and other subnational governments or support for the production of local versions; and some have stepped forward to fund initiatives on subnational implementation.

What remains now is to continue pronouncing the importance of cities in the achievement of the Strategic Plan at every opportunity, especially when “preaching to the un-converted”, and particularly when preaching to national governments. The TNOC community is considered one important source of these sermons!

Andre Mader

Montreal

Leave a Reply