‘There is nothing in a caterpillar that tells you it’s going to be a butterfly.’

—Buckminster Fuller

Architecture | Education | Landscape | Nature

It’s been six months since Sweet by Nature was penned and released into the ether and in less than a week’s time, my students at the University of Johannesburg (whose work was featured in the article) will submit their Masters projects for external examination. In that time, I’ve not only come to understand better what it is I’m supposed to be teaching them, but also where the potential gaps in the overall structure of architectural education—particularly in Africa—may lie.

One such gap has to do with ‘nature’ and specifically what we mean by ‘nature’ when we teach architecture. It may seem like an obvious point but education, even in the context of a semi-vocational/professional course like architecture, isn’t just about the delivery of an ‘approved’ curriculum, it’s also (perhaps more deeply) concerned with the transmission of values. In the context of Africa where the very idea of shared cultural values that transcend the specificities of place, language, history and even ‘race’ remains an elusive pipedream, the question of how we might teach an approach to ‘nature’ and by extension ‘landscape’ remains equally elusive.

By and large, African schools of architecture follow curricula handed down/derived or adapted from one colonial context or another—British, French or Portuguese. South Africa’s eight schools have an added Dutch/Afrikaans layer of cultural complexity to contend with, but I believe it’s fair to argue that African schools have yet to attempt the profoundly complex translation of indigenous, pre-European built environment beliefs, rituals and ways of seeing into a functioning modern architectural curriculum. Given the explosive nature (no pun intended) of urbanisation, the question of how we define, explore, protect and appreciate nature and landscape in relation to urban growth is particularly urgent.

In his ‘Preface to the Second Edition of Landscape and Power, the American scholar and art historian William Mitchell wrote, ‘if one wanted [to] insist on power as the key to the significance of landscape, one would have to acknowledge that it is a relatively weak power compared to that of armies, police forces, governments and corporations. Landscape exerts a subtle power over people, eliciting a broad range of emotions and meanings that may be difficult to specify.’ Although the terms ‘nature’ and ‘landscape’ are certainly not inter-changeable, for the purposes of this article at least, I’m drawn to a definition of both that is deeply intertwined, if not co-dependent. Edward Said’s notion of ‘imaginative geography’, the invention and construction of spaces that are mapped (and conquered) in the mind as much as they are in any geographical actuality is particularly useful. As he writes, ‘the great voyages of geographical from da Gama to Captain Cook were motivated by curiosity and scientific fervour, but also by a spirit of domination, which becomes immediately evident when white men land in some distant and ‘unknown’ place [the emphasis is mine] and the natives rebel against them.’

It isn’t possible to speak of ‘landscape’ in Africa without reference to ‘displacement’: the replacing of one geographical sovereignty over another. What isn’t as readily graspable is how to tackle the residual cultural/emotive struggles over territory, which involve multiple and often overlapping stories, memories, narratives, experiences and, all too often, physical structures. Here, as I alluded to in my previous post, ‘questions of ownership still dominate the discourse around “land” and “landscapes”: who “owns” the land, on whose terms, in whose image, according to whose beliefs and practices?’

South African cities, uniquely, can be defined in three quite distinct ways: township, city and suburb, and in each, nature plays a particular role. The leafy northern suburbs of the city constitute the world’s largest man-made urban forest, defined as a collection of trees that grow within a city, town or suburb (note: not township). In its widest sense, it includes any kind of woody plant vegetation growing in and around human settlements. In a narrower sense, it describes an area whose ecosystems are inherited from wilderness ‘leftovers’ or remnants. Johannesburg’s Northern Suburbs are said to contain between 6 and 10 million trees, and although the claim is often disputed, Wikipedia says it’s true.

Irrespective, as an outsider to Johannesburg in all senses of the word, it’s easy to see why the claim holds such sway. I don’t recall ever being in a city—anywhere—where the difference between two ‘faces’ of the city is quite so stark. Nature here, far from being the gentle pacific force that tempers hard (and often harsh) urban reality, is a weapon that distinguishes one profile from another, softens selectively and purposefully, rams home an insidious, unpalatable truth: nature isn’t for all; only for some.

Truth | Beauty

One of the most poignant conversations I’ve had in a long time—anywhere—was held a fortnight ago in Braamfontein, one of the inner city’s up-and-coming regeneration ‘success’ stories. I asked a young black architect what had ‘turned him on’ to architecture (as a possible profession).

‘I grew up in the Cape Flats,’ he said, not without a trace of bitterness, ‘without a tree in sight, nothing but concrete all around us. I had my fifth birthday party in the garage of our house, not the garden. There wasn’t one. That’s what all the kids around me did. We had our birthday parties in our garages. I used to look at the city on the slopes of Table Mountain; look at those leafy suburbs and think, “I wanna live there. I wanna live like that. Those leafy suburbs. That’s what got me. Now I live in Melville. It’s leafy, real leafy. If you ask me what made me choose architecture, it was beauty, just wanting to live in a beautiful place. Yeah, beauty. Or maybe the lack of it, y’know?’

His comments stayed with me long after the conversation ended. As another South African once said:

‘The truth isn’t always beauty, but the hunger for it is.’

Mind the gap: drawing ambience

Having watched my students’ projects literally grow over the past six months, the question of drawing has stubbornly remained uppermost in my mind. How to draw? What to draw? What to expect from a drawing? What to explore, what to explain? Coincidentally (although I’m beginning to understand that nothing is coincidental), I’m about to leave for the U.S. to take part in a panel discussion at Washington University, on the pedagogy and practice of drawing and architecture worldwide.

The invitation comes at precisely the right moment: at the University of Johannesburg, a quiet-but-pivotal change is about to take place that connects the department of architecture to the panel discussion in an unexpected way. Organised in conjunction with the exhibition Drawing Ambience: Alvin Boyarsky and the Architectural Association, the Mildred Kemper Lane Art Museum in St Louis will ‘present the first public museum exhibition of architectural drawings from the private collection of the noted educator Alvin Boyarsky. Amassed during Boyarsky’s tenure as chairman of the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA) in London from 1971 until his death in 1990, the collection features early drawings by some of the most prominent architects practicing today—Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, and Bernard Tschumi, among many others. Through a selection of approximately forty prints and drawings that constitutes the bulk of this collection, as well as nine limited-edition folios published by the AA—including works by Peter Cook, Coop Himmelblau, and Peter Eisenman—Drawing Ambience offers a rare glimpse into a pivotal moment in architectural history and the imaginative spirit of drawing that was and continues to be instrumental to the development of the field.’.

Boyarsky was the architect (no pun intended) of the now-famous Unit System of architectural education, which eschewed the traditional approach to teaching architecture in favour of a radical educational model that is now followed in architecture schools across the world. Instead of a standard curriculum, the Architectural Association (AA) allowed tutors to construct their own educational structures, with students free to choose the approach that most interested them. The AA thus heralded the move from modernist orthodoxy to a much more pluralist system. Boyarksy encouraged debate—and sometimes conflict—between the units, so that work was always subjected to a variety of opinions. The AA in the 1970s and 1980s also hosted key architectural lectures and debates, becoming an international hub for the development of architectural discourse. Many of the world’s most famous architects, including Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, emerged from the intense environment that the AA constructed.

As of February 2015, the University of Johannesburg will be the first school of architecture on the African continent to adopt the Unit System. Central to its success is an approach to drawing that sees the emphasis shift from ‘drawing-as-a-means-of-explanation’ to ‘drawing-as-a-means-of-exploration’. It’s an important distinction but a complex one and in order to make the point more clearly, I’d like to step sideways for a moment, and speak not of drawings but of novels.

When the word ‘novel’ entered the languages of Europe, via Don Quixote, considered to be the first European novel, it had the vaguest of meanings. It meant—as its name suggests—something new: a form of writing that was formless, that had no rules; that made up its own rules as it went along. It captured—and represented—the collision of a number of different forces: urbanisation, the spread of printing, the availability of cheap paper, and it began the tradition of an intimate reading experience that has endured to this day. For cultures without the written word—like the majority of African cultures—that relationship between intimacy (the solitary act of reading or drawing) and performance (those aspects of oral storytelling and communal building)—is one that we grapple with—or at least should grapple with—today.

But we don’t, at least not in any part of the African continent that I know of. In the context of African schools, like it or not, staff and students must necessarily act simultaneously as interpreters and investigators, explaining a world that is often invisible to Western-trained ‘eyes’, both to themselves and others, yet at the same time exploring it in all its depth. It’s a difficult, complex task. As I’ve written elsewhere, ‘there is something deeply interesting and complex happening here [in African cities] if we could only work out how to see it.’

Using the drawing as a means of exploring, not explaining, seems to offer African students (and let me only speak about students here, not practitioners or professionals) a way out. For me it represents a real triumph of will—not only in the context of global speculation about architecture and architectural education, but particularly in the context of Africa, which has never ‘deserved’ to be speculative. Too many toilets to be built, too many people to house, too much poverty and chaos, and too many problems for such esoteric speculation: that’s Africa for you. Well, for us.

But I’ve never held that view, not even as a student, and I certainly don’t know. There’s a lot of work to be done to reconfigure a curriculum that better serves our needs—and I’m not talking about sanitation upgrades or social housing—but rather that gap in the title of this section between exploration and explanation. For me, the speculative, deeply explorative space of design research begins with a new relationship to, and with, drawing. I don’t know about you—and I certainly don’t know yet about my students—but I’m hugely excited by the possibilities that a new relationship might bring.

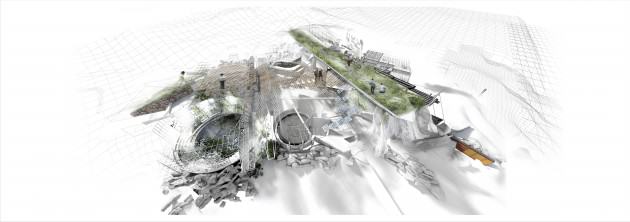

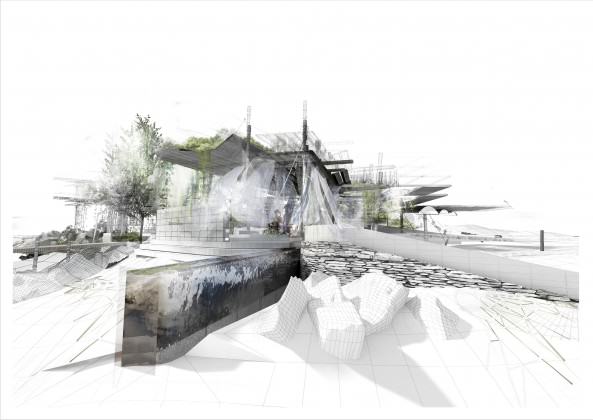

Here’s where some of those drawings ‘grew’ to.

Here’s where some of those drawings ‘grew’ to.

R Wilson Drawings 10/02/03

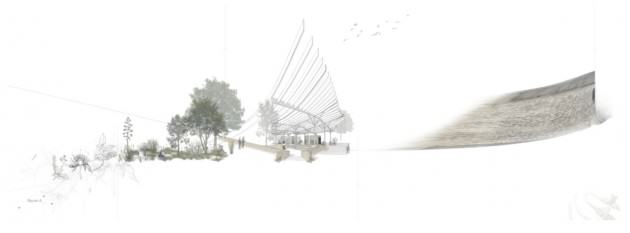

Rachel began the year exploring what she perceived as the breakdown in society between extreme consumerism and Johannesburg’s fragile ecosystems. In her final proposal, which she has re-named ‘The Sensitive Landscape’, she uses the drawing rather like a loom, shuttling back and forth between techniques, views, ‘man-made’ and ‘natural’ forms. In her own words, ‘this is a project that takes full advantage of the play between light and dark, secrecy and open-ness, obscurity and fame. Small pleasures, often unnoticed or forgotten, are rediscovered. The smell of a particular plant, placed at the entrance, or a light effect that occurs only under specific weather conditions allow the user’s consciousness to expand in small but meaningful ways.’

In many ways, her own drawings are analogies for the unfolding of her design: sub- and often unconscious, intuitive, expressive and sometimes ‘blind’, she has allowed a different language to enter the design process: in place of certainty and precision, she has made room for doubt, for accidental discoveries—a different technique, a particular quality of light, for example. Drawings that are literally full of the ‘small pleasures’ she sought to express.

T Melless Drawings 01/02

In an even dreamier, drift-like and alliterative way, Tiffany eschewed the conventions of plan, section and elevation to allow a different built proposition to emerge. This is a project driven largely by intangibles: sight, sound, smell. At one level, the entire proposal is a route—through rituals, gardens, landscape and even the city. Frangipani plants sit next to mint: the combination of specific scents is intended to evoke specific memories. A stone wall becomes mossy over time; plants creep and curl their way around latticed screens, providing a dappled roof in Johannesburg’s high, sunny winter. You walk the drawings (some are up to 2m in length) in the same way you might walk through the site. There’s a clear relationship in Tiffany’s work between the site that exists out there, in the ‘real’ world and the site of her imagination: through these beautifully expressive drawings, she manages to pull the two ever closer together.

G Coter Drawings 01/02

Gabi’s starting point for the year was a clinic. Under (gentle and then not-so-gentle) pressure, she began to move away from the conventional notion of a clinic, first through the use of a well-placed ‘’’ (‘Clinic’), then, slowly, through the use of a different type of drawing: needles and pins; ink and film; water and light, shadow and X-ray. In her own words, ‘this project seeks to understand landscapes not just as blank spaces to be gazed upon, but as territories imbued with their own meanings. With a particular emphasis on healing, regeneration and restoration, the design project attempts to restore memory and dignity within the Rietfontein Farm by investigating recycling, landscape fertilisation and restoration to imbue the site with new meaning and usage. Using the notion of the ‘clinic’ as its point of departure, the project develops a series of architectural interventions that can be found in the hints and clues about its past and past users: forgotten graves, abandoned buildings, a defunct hospital and wastelands.’

These drawings represent a radical departure from the conventional black lines-on-white paper that Gabi began the year with: burning, scoring, tracing, cutting, lacerating—these have become as much a part of her architectural ‘vocabulary’ as any CAD-generated section might once have, and the project is all the richer for it.

Z Goodbrand Drawings 01/02/03/04/05

‘Average’ students typically take up half a room at project’s end: Zoë takes up two rooms, possibly more. This year, she has moved between model-making, conventional drawings, landscape urbanism, videos, montages, collages, city council meetings and texts to produce a body of work that is both astonishingly thoughtful and thorough, no mean feat.

Using scale as a means to organise her thinking processes and her representational choices (from regional through metropolitan to the neighbourhood and architectural scales), she has managed to extract a way of working—modeling, filming, mapping, planning, envisioning—that not only serves the four scales of her project exceptionally well, it has driven her design decisions: a cycle-in cinema; an allotment farm and market; a ‘kinetic’ forest that is at once landscape, art and education facility.

W Matthews Drawing 01

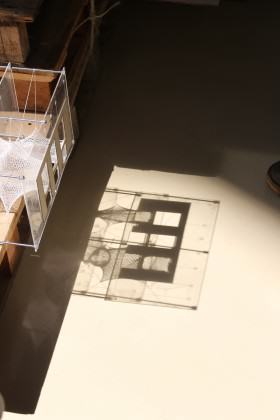

Although Wayne’s work wasn’t featured in my original post, in some ways, his ‘journey’ from convention to experimentation has been the most impressive. A former engineering student, in whose work traces of the impulse to structure, order, explain and classify can still be seen, he has learned to move sideways into slippery, unfamiliar and intuitive territory, allowing the drawing to ‘lead’ him, sometimes against his own will, towards an even more precise resolution of ideas than he might otherwise have thought possible.

His chosen site was an abandoned power station just outside Soweto: in a moment of almost Biblical calumny, halfway through the year the ruined power station collapsed as a result of illegal salvage operations: a metaphor for his own way of working. Phoenix-like, a new project has emerged, playful, dextrous and powerful at the same time, with a lightness of touch that surprises everyone who sees it. In this image taken during his final presentation, a ray of light pierced the examination room, casting a perfect shadow on the ground. A photograph led to a new drawing, which in turn led to a new model—the perfect synthesis of time, chance and place.

* * *

It’s hard to summarise a work that is still in progress: these five projects remain a snapshot of a desire that is still partially unfulfilled. In many ways, they have come about through acts of resistance: to convention, to orthodoxy, to established norms and expectations. They express (albeit tentatively) a desire to move beyond a known language into another, more ambiguous realm, neatly sidestepping the dilemma I sketched out earlier: the impossibility of being interpreter and explorer in one.

There’s a gap here, as I have already said, but the role of the school (the educator, the pedagogue) isn’t to fill it, or to answer ready-made questions. In my view, at least, our role is to protect and cherish that gap, so that the tentative propositions put forward through new ways of working/seeing/drawing and thinking will have acquired the maturity and sophistication of genuine knowledge, not open-ended, self-absorbed exploration.

Mind the gap. Caterpillars too have their own persuasive beauty. Just saying.

Lesley Lokko

Johannesburg

Oops. Thanks Tim. I stand corrected—I got confused by the orange vs. yellow spots.

Anise Swallowtail, Papilio zelicaon

Most enlightening! Now I understand where you are coming from – or going, I should say, especially in the context of our discussion at Stanley 44. I hereby declare my commitment to assist in the Masters Unit system next year. I trust my passion for ballpoint pen drawing; thinking through drawing, design and craft will provide a creative platform for students to realize, visualize and launch their creative concepts and ideas in finding design solutions in practice.

Differentiating it from anise swallowtail by recognition of the larval plant ? Reiko thinks it looks like a carrot, parsnip family plant but can’t make the call one way or another. Or is it the coloring of the wiggler that makes it a clear call?

Black Swallowtail

Papilio polyxenes

I have not read the entire article yet, but can someone tell me about the last photo of the catapillar that is striped in green, black, orange & yellow? Several of them ( 3-4 ) 1 inch in long plus a small baby, just showed up on the parsley. San Diego, CA area. Coastal area. Thanks