about the writer

Jennifer Adams

Jennifer D. Adams is an associate professor of science education at Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, CUNY. Her research focuses on STEM teaching and learning in informal science contexts including museums, National Parks and everyday settings.

Jennifer Adams

How can art be better catalysts to raise awareness, support and momentum for urban nature and green spaces? This was a hard question for me to address because of the way art, urban nature and green space are positioned vis-à-vis each other as if they are separate, however both subjugated to some dominant discourse of the role of art and nature in urban contexts. The question seems to position art and nature at the margins of urban life and one is needed to raise the awareness of the other. However, as bell hooks notes, agency is at the margins because it is here that a discourse that is created that is counter to the dominant discourses of power and causes us to rethink the kinds of relationships that we have not only with each other but also with the places in which we enact our daily lives. Urban nature and green spaces are these places. Art happens in these places. These places exist and are in our awareness, however this awareness may not look like what the dominant discourse of environmental awareness dictates.

Embodiment of art and nature

Sunday morning, a circle of grain marks a sacred space. A gentle pulse builds to a strong beat. The pulsing of the Earth resonates in the rhythm of drummers’ hands on skin rising up and filling the space between the trees. Dancing feet pick up dust as moving bodies, twirl and jump, marking time with the rhythms of the Earth. In the sacred circle, “places, memory, experience, and identity are woven together over time.” In this space, time collides, moves and stands still. The expression of it all is in a breath, a breath that circulates carbon and oxygen and connects living and non-living beings.

The art that I describe here is a participatory art that happens in an urban green space. It is a weekly drumming circle that draws dancers, drummers and appreciators into the space to create a collaborative and fluid expression of art. The location of the circle, in a public green space, is essential to the production and is a part of the creation of the art. This art cannot be described separately from the space in which it occurs or the place it creates. “Dancing bodies accumulate spirit, display power and enact as well as disseminate knowledge,” notes dance scholar Yvonne Daniels. These dancing and drumming bodies create a sacred space, in an urban green space, that connects them to the present community and to communities past and future, transcending the time-space continuum. Mos Def describes African art as functional art, “it serves a purpose. It’s not a dormant. It’s not a means to collect the largest cheering section. It should be healing, a source a joy. Spreading positive vibrations.” For Mos Def and many others, art is not a separate product from the culture that produces it but rather it is intertwined with the daily lived experiences of people who come together and participate in its production. It is also connected to the spaces in which it is produced, in fact art, as a process, creates places and some of these places are what we are calling urban green space and urban nature in this roundtable.

Art is how people connect with green spaces. We sometimes take for granted those participatory forms of art—drumming, dancing, singing, cultural rituals—of which green spaces are an important context for them to occur.

I included a vignette of Drummer’s Grove in Prospect Park because it has been a part of my lived experience as a life-long resident of Brooklyn and it is an example of collectively produced art that represents embodied culture and identity and is not separate from the green space in which it is both produced and enacted. Although West African drums and drumming style dominate the circle, you can also find drums that are representative of indigenous people and other diasporas that find themselves connected to this park—Native American, Middle Eastern, Indian and Celtic to name a few. Thus the art is representative of the urban green space in which it is produced and belongs to anyone who visits the sacred circle.

Art reflects who we are and our relationships to place

As a scholar who is interested in understanding the different relationships people form with places and the relationship to identity, I do not view green space and nature as separate from urban life. It sets up a false human/nature dichotomy and positions urban life as something unnatural. It forces us to use language around raising awareness, support and momentum without asking from whose perspective are we speaking; in other words what does this awareness look like in action? Is this along the lines of the dominant discourse of pro-environmental behaviors and preservation of nature (as if it were something to be viewed, like from behind glass and not to be engaged with)? From the perspective of art, is this only the art that is sanctioned, sponsored, commissioned to “catalyze” a particular view of the environment?

As we enter the new age of human impact, that some are calling the Anthropocene, we need to rethink our relationship to the Earth and this includes in the urban spaces that we occupy. We not only need to think about the different kinds of relationships that people have with their environment, but also the different ways that green spaces appears in urban environments—it ranges from large, manicured parks, to wildlife preserves to small patches of trees and grass that dot the sidewalks, and includes the humans and non-humans who interact with and create these range of places. All of these spaces make up the fabric of urban life. And while there may be a taken-for-grantedness towards urban “nature,” because it is all around us, just like certain art forms are all around us, maybe the awareness we need to raise is that of honoring diversity in all of the ways it is present. Urban spaces, grey or green, allow us to do this in authentic ways. Perhaps more attention to the arts as expressions our place-relationships will allow us to broaden our perspectives about the different ways we connect to our world.

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

Graffiti is generally an illicit or prohibited art form, which when combined with the frequently anonymous nature of graffiti, makes it inherently provocative. Graffiti is no gallery-selected piece, or municipal-funded art project, but the work of an individual who feels the need to make some sort of publically visible ‘statement’. The rationale for graffiti are numerous (see here) but true to all graffiti is that it is visible to a broad sector of the public, which, combined with its frequently provocative nature, makes it a very powerful medium.

In the City of Cape Town there is a fair plethora of nature-based graffiti with depictions of wild life, mountain-scape scenes, and commentary on conservation concerns dotted around the walls of the City. Here the need seems to be primarily a drawing-in of nature to the City, and a demand to engage in or be aware of conservation issues. The audience seems to be both the citizens as well as the authorities. There is a call for renewed engagement and energy from the people of Cape Town, and simultaneously a demand for a more accessible, integrated, available, and people-owned nature in the City. It seems to me it is just the kind of art in question here: the sort that raises awareness, support and momentum for urban nature and green spaces.

The question of how to make this art form a better catalyst for urban nature is a tricky one and probably comes down to a simple promotion of more of the kind of work already underway. Support in the form of legitimization could detract from the status graffiti has as ‘unsolicited public voice’ and ‘anti-authority’. Nature-based graffiti really takes both nature and art out of the realm of the middle-class and I think this aspect of graffiti is where the power and potential lies in allowing a different voice to enter a realm, certainly in Cape Town, that is often seen as elitist.

Perhaps what is needed is philanthropic support for those artists who work in this space. For example funded global exchange programmes, conversations between artists and ecologists, and nature-based graffiti art competitions, could all boost the scope and capacity of this community of artists. The difficulty here is that the anonymous and often transient nature of graffiti makes it unappealing to most funders who look for ‘bang for their buck’ with the kind of metrics unlikely to be found in an art work that must be anonymous, un-fettered, and might be erased overnight be vigilant anti-graffiti authorities. I think the dividends however in reaching many people are high, but not captured by standard metrics.

It would seem that the volume of nature-based graffiti in the City of Cape Town is somewhat higher than in other cities around the word, and it is possible there is something South African going on here. A long history of anti-government sentiment, and an associated disregard for authority, a pride in taking action, the circumstance of a country with significant natural biodiversity, and the process of giving voice to the voiceless might be a combination that is a South African legacy.

So a final note on how to sustain and grow this informative art form would be to foster these elements of civic engagement, especially among the youth where a natural inclination to rabble-rousing could be put to good effect with ongoing exposure to nature to develop a sense of custodianship which would in turn inform creative and artistic outputs.

about the writer

Marielle Anzelone

Marielle Anzelone is an urban ecologist whose work centers on people’s daily connections with nearby nature and the role that design, education, and government can play in fostering this relationship. She is the founder and executive director of NYC Wildflower Week—an organization that produces cultural and educational programming to engage urbanites with the wilds of the Big Apple.

Marielle Anzelone

I’d like to be able to say that I was inspired to create a public art project for lofty reasons. To reconnect urbanites with nature, for example. Or to build more habitat for wildlife. And while these elements are fundamental to the project, the actual catalyst was much less prosaic.

The inspiration for my art was frustration.

Our cultural zeitgeist has a design fetish. We swoon over celebrity architects and devote television shows to fashion designers. Anything transformed by human hands is deemed cool and sexy, including built landscapes. Cities are a favorite canvas because they are defined as lacking nature. Here landscape architects, among others, are keen to conjure urban forests, introduce native wildflowers, and restore ecological function. But cities are not a clean slate. Not even New York City.

It is easy to forget that modern New York City exists because of the abundant greenery that once defined it. Early Dutch sailors reported being disoriented by the scent of wildflowers wafting out to sea from Manhattan. Certainly no one has that experience today.

And yet, amazingly, forests, marshes and meadows have survived. Today, natural areas cover nearly one-eighth of the Big Apple, more than any other city in North America. Despite this rich natural heritage, New York City’s iconography is limited to taxi cabs, the Empire State Building, and Jay-Z—all hardscapes and humans. With nature excluded, original green spaces get little funding or attention and worse, are often threatened with development.

New York City’s natural areas consist of wildflowers, insects, soils, trees, sedges, and birds that evolved in situ over thousands of years. That kind of complexity is impossible to mimic in a built park. Red oaks brought in from nurseries in Michigan have different genotypes than our extensive local populations. In the drive to make their mark, designers largely overlook opportunities to support what we already have.

For example, the Red Admiral butterfly is a migratory species and pulses of them flock through New York City every spring. The same is true of other insects and many birds. Large natural spaces provide a mosaic of habitats to sustain a variety of wildlife. The trouble is no one designs with this in mind. When local forests are lost to ball fields or big box stores, all of that is lost too.

The problem is further compounded by location—reserves of open space tend to be far from our everyday lives—and out of sight is out of mind. The lack of civic interest in local conservation issues gave me an idea. To spark the public’s imagination, I needed to introduce ecology into the dialogue of urban design. My solution is PopUp Forest: Times Square.

PopUp Forest: Times Square will give visitors an immersive natural area experience in the most iconically un-natural place on the planet. We will transform a public plaza in Times Square into a large-scale temporary nature installation. Filled with towering trees, native wildflowers, and mosses and ferns underfoot, it will bring a piece of wildness to the heart of Manhattan.

The installation will feature guided woodland walks, interpretive signs, and hands-on educational activities. It will provide habitat for migratory springtime warblers and vireos and Red Admiral butterflies. Street noises will be muffled, and wildlife sounds will be piped in live from nearby woods. Then after three weeks—it’s gone.

This full sensory experience will open our eyes to the wild elements that share our urban home. I want this art to not only encourage people to rethink the way we aim to ‘green’ New York City, but also shake up our ideas of what cities ultimately can be.

Click here to learn more about PopUp Forest: Times Square. Or contribute.

about the writer

Stephanie Britton

Stephanie Britton is the founding Executive Editor of Artlink magazine, the visual arts quarterly established in 1981 in Adelaide, South Australia.

Stephanie Britton

Algae hacking, the Plastiphere and living off thin air

Artists who make work dealing with the natural environment do this sometimes in galleries with installations about water use, plants, forestry, loss of habitat, species extinction etc. The context of these installations is crucial to their knock on effect. If they take place in a typical precious white cube space the effect is minimal. If in a regional or less polished space they have more impact as a wider range of people actually see them, and the discussion framework around them is more likely to involve other artists, biologists, gardeners, activists, ecologists and lead to fruitful synergy and collaborations. White cube installations are seen first as a commodity on sale to a collector—whether that be a museum or an individual—and the ecological subject is the secondary message that comes through. Despite the fact that the artworks are laudable and interesting they are all too often limited to being attractive things with plants and water—with or without olfactory or tactile elements—rather than a means of opening up of new awareness and effecting change.

An example of the opposite was Michael Harkin’s piece at Bendigo Art Gallery in the state of Victoria, Australia, which used the town water supply data flow to reveal how much water was being used in real time by the citizens of this medium sized Australian city. The fact that it was created towards the end of one of the region’s longest droughts provided the element of urgency, and the uncomfortable sensation of witnessing the casual waste of the precious water that remained in the dams. Visitors to the Gallery stood spellbound in front of the endlessly changing data display which was sensitive enough to reveal when taps were turned on and off, toilets flushed, washing machines set in motion. The electronic sequences were translated into a work of sound and light playing on elements in the gallery suggesting traditional water tanks.

Guerilla gardens have sprung up in Sydney and Melbourne and other cities, and sometimes these are condoned, even supported by local councils, but often they have a limited life. There are examples of architects working with artists to realise works of public art which incorporate living green, but they are few and far between, and are either so abstracted that they are not perceptible as real plant life, or they are so fragile and vulnerable that they disappear after a short time.

Sustainability is the hallmark of the work of artist Lloyd Godman (who also writes in this collection of essays) who grows bromeliads which only need air to live. He has created large pieces of public art in Melbourne which hang in space or are attached to buildings, made up of these air plants. The difference between this and other attempts at greening the city is that they are designed to last indefinitely. The plants are capable of living for many years, and their slow pace of growth means that they become thoroughly self sustaining. The battle that such artists have to wage to persuade city managers to strike out into these domains of public art, can be daunting for most individuals in the West, where the public domain is massively regulated and controlled by layers of traditional thinking.

Working within a somewhat different set of parameters, Belgian artist Ivan Henriques has created a series of what he calls ‘Symbiotic Machine’ (SM) which engage photosynthesis in an intriguing way.

“SM is the creation of a prototype for an autonomous system that can achieve the basic needs of life: be able to find its own food to have energy to search for food again. This bio-machine hacks the electrons provided by the photosynthetic process that occurs in the algae spirogyra. This specific algae is abundant in the Dutch landscape—mainly found in ponds and canals—a filamentous organism that releases oxygen during the photosynthetic process, in turn creating bubbles which make this filamentous mesh of algae float.

“In order to ‘hack’ the algae spirogyra photosynthesis and apply it as an energy source, the algae cell’s membrane has to be broken. The SM prototype was designed within the disciplines of engineering, biotechnology, art and design to accomplish a condition—to make photosynthesis to continue its life cycle (1), like a plant.” [1]

This kind of work, known as Bio Art, is breaking the boundaries of art and green thinking, where the very matter of biology and the definition of ‘plant’ is opened up so that machine and plant can become one, and not only can life be sustained by a symbiosis of the two worlds, but, in theory at least, this can be used to clean watercourses which have been polluted. Could this new frontier be a way of thinking about how self-sustaining ‘biological design’ could enter the urban fabric? [2]

Another Bio Art practitioner, Pinar Yoldas, (Berlin) proposes that the gyres of plastic that have formed in the South Pacific challenge us to contemplate the coming of a ‘Plastisphere’—an ocean zone in which a new species will evolve from the minute particles to which the world’s trash has been reduced by the action of the waves. This new species will have its own nature parallel to the plant and animal kingdoms.

“Scientists from Brown University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution recently came up with the term ‘Plastisphere’ to describe the transformation of our marine ecosystems into a human-made plastic soup that generates new organisms and new microbial reefs even on the smallest plastic particles. Pinar Yoldas moves from observation and documentation to speculation to present a colourful future scenario that has its origins in the past and will continue to run its course no matter what.” [3]

One might speculate what could happen if China’s fast tracking of ecocities from the ground up or adapting existing cities like Chengdu, were to take on board the inventive projects of artists working with self sustaining natural elements.

A life cycle with functions was idealised in order to program the machine and activate independent mechanical parts of the stomach: it has to eat, move, sunbath, rest, search for food, wash itself, in loop.

[1]—Ivan Henriques, ‘Photosynthesis, electric motor: the Symbiotic Machine’ Artlink Vol 34#3 “Bio Art: life in the Anthropocene”, Sept 2014, pp26-29,

[2]—Artlink Vol 34#3 “Bio Art: life in the Anthropocene”, Sept 2014, pp30-33[3]—Ingeborg Reichle ‘Speculative Biology in the Practices of BioArt’

about the writer

Pauline Bullen

Pauline E. Bullen, PhD, currently teaches in the Sociology and Women and Gender Development Studies Department at the Women’s University in Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Pauline Bullen

I have recently moved from New York City where artists continually reclaim urban spaces marked by age, dust and dirt with dynamic wall art (graffiti or street art), performance art and more and their works are often found side by side with thriving community gardens, parks and playgrounds. Works appearing in varied venues, such as community gardens often facilitate interactions amongst people and between people and spaces, in richer, more spiritual and dynamic ways.

In Harare, Zimbabwe where I have been living for the past year, I have strolled through and driven past community flower, art and sculpture gardens and have had the pleasure of observing much that is astonishingly beautiful, such as the lavender and purple glory of the Jacaranda trees in September and October, and sculpture gardens open to the public such as one that exists on the grounds of the National Gallery which features large and dynamic works by artists like the internationally renowned Dominic Benhura, who captures forms and feelings in ways that are incredibly real. I however, have also noted a great deal of waste and neglect primarily as a result from misuse and divergence of public funds. As a result the majority of individuals and whole families scramble for clean water, not to water the beautifully manicured lawns that some are privileged to maintain but to feed them selves. With better regulation and use of funds, government commitment to provide jobs, accessibly clean water, improved roads and transportation system, more frequent and reliable garbage collection, a community clean up campaign to build awareness and co-operation amongst the people regarding the health benefits of clean and green (less toxic) spaces would perhaps then be impactful. There may then be more respect for areas, including rivers, which become garbage dumps. There might be less frequent fires—fires to burn garbage and fires indiscriminately set that destroy trees, shrubs and grasses but also chase out wildlife in order to feed poverty and hunger in this country with its 90% unemployment rate. Throughout Zimbabwe works of art appear in well manicured front and backyard gardens, in areas deemed to be “high density” and in villages in the countryside and it appears that the general population barely ‘see’ there significance or notice their presence as they scramble to survive.

In the National Gallery of Zimbabwe there are permanent and temporary installations that demonstrate the creative and recreative nature of the people and speak to a number of current issues that trouble the community—gender based violence, child marriages and more. Permanent installations can also speak to a vision of a cleaner and greener urban center. A recent visit to one relatively small gallery in Harare allowed students to view landscapes commissioned by artists who were able to capture the varied nature of lands in particular parts of the country and the students were tasked to think about what scenes they, as artists, would want to highlight in their works—scenes that would not feed racist and voyeuristic ideas of a primitive Africa only suitable for safaris.

In the National Gallery of Zimbabwe there are permanent and temporary installations that demonstrate the creative and recreative nature of the people and speak to a number of current issues that trouble the community—gender based violence, child marriages and more. Permanent installations can also speak to a vision of a cleaner and greener urban center. A recent visit to one relatively small gallery in Harare allowed students to view landscapes commissioned by artists who were able to capture the varied nature of lands in particular parts of the country and the students were tasked to think about what scenes they, as artists, would want to highlight in their works—scenes that would not feed racist and voyeuristic ideas of a primitive Africa only suitable for safaris.

Another recent exhibition took individuals on a walking tour of the city to view original art works hung in varied and unexpected sites, a barber shop, the lobby of a hotel or government office, bus depots, supermarkets and more. It was said that, “artists were invited to submit an alternative reality through lens-based media”. In a huge plot next door to a shopping center I frequent, a gazebo was erected from recycled coca cola cans. There, works are developed from stone, wire, rubber, fabric and scrap metal, and all of these speak to a profound connection between the people, their surroundings and their fundamental need to provide even the basics for themselves and their families.

Projects like these and many more, may be adapted to interrogate the reasons for the deterioration of the ‘grey’ areas of the city and to promote the need for co-operative ‘green’ spaces.

about the writer

Tim Collins

The Collins + Goto Studio is known for long-term projects that involve socially engaged environmental art-led research and practices; with additional focus on empathic relationships with more-than-human others. Methods include deep mapping and deep dialogue.

Tim Collins

Reiko Goto and I have moved back and forth from urban postindustrial sites to natural exurban sites in our art, ecology and planning practice for over thirty years. As artists we engage the world in cultural terms working with ideas, perception, experience and value. Current work engages plant physiology and the ecology of the human body as well as landscape. I would like to ask the reader to entertain the idea that urban nature has robust experiential value and can have eco-system authenticity but it primarily serves as a cultural ecology. Its power emerges in dialogue with images and media, narratives, scientific characterization and actual experience with exurban nature. The value of intimate daily experience and inter-relationship with nature cannot be minimized.

Living in Scotland these days I feel like Patrick Geddes and Ian McHarg are always nearby; they differ from others involved in landscape, art and planning through an essential interest in embedded and embodied experience rather than a distanced gaze, a visual relationship to the world around us. Below you will find a few thoughts from recent writing after spending a year working with the social scientist David Edwards and a group of scientists, land managers artists, humanities experts and resident community interests, thinking about an ancient semi-natural forest in the Highlands of Scotland.

A few ideas for a critical Forest Art Practice

—Establish a model for art with forests rather than in forests. Considering the process, method and form of art as ephemeral forest interface and as a correspondent image that works across the urban and the rural.

—Experiment with the idea of empathic exchange between people and trees, to consider the ways that trees and forest embody culture and how people embody the forest in daily life, regular practices or celebrations.

—Consider how art might contribute to the potential well-being or prosperity of a tree or forest community in the age of environmental change.

Thinking and being with the Black Wood of Rannoch, Scotland

In 2014, the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) was selected by the Scottish Government to be the national tree of Scotland, yet the social and cultural relationship to the Caledonian pinewood ecosystem is limited. It is neither an image nor a concept that has much traction in archives and museums or parks and botanic gardens in the cities of Scotland. It is an icon lost in time without a body or image for most urban Scots. As the southern-most large (only one of ten that are more than 1000 hectares) Caledonian pine forest, the Black Wood survived (where others did not) due to isolation and a lack of access. There is one road in and out of Rannoch on its eastern end, and a train line on its western end. Whether one arrives by train, car, foot or bicycle, most will struggle to find the Black Wood of Rannoch.

During the rut, nights in Rannoch resound with the calls of the stags, one quickly realizes this is a place where there are more deer than people (although this was not always trues.) There is one Forestry Commission sign identifying the Black Wood, it is easily missed, as it is set back and parallel to the Loch road. Another can be found a half-mile down a dirt road at the western edge of the Dall Estate. The Black Wood borders the southern shore of Loch Rannoch; between Dall Burn to the east and Camghouran Burn three miles to the west. To get into the forest one follows any one of four trails that move in a southerly direction. One enters the Black Wood moving gently uphill, the forest is alternately open and closed with a mix of birch and pine, and some rowan and juniper, all growing across a range of age classes from saplings to mature trees. The most memorable trees of the Black Wood are the 200-300 year old ‘granny pines’ with their sprawling limbs. One is immediately struck by the forest and its relationship to a curious topography; a mix of small glacial ‘moraine’ deposits or hillocks with a never-ending repetition of smaller hummocks of thick blaeberry, cowberry, bracken and heather. The hummocks are vegetation formed over large rocks and tree stumps, creating an unusual ‘lumpy’ forest floor that adds texture to the rolling mound-and-hollow topography. But it is the granny pines that are worth talking about: why are they here and why so many of them? What is the relationship between these broad branched trees, and the traditional foresters’ ideal of a tall straight trunk?

Moving through the forest along the western-most trails the casual walker will notice changes to topography, the small hills and valleys of the moraine field. This can also be understood as wetter and drier areas. Walking in a southerly direction (towards the summer hill pastures of the transhumance) the forest opens up to the south, where a bog is clearly visible through the trees. Those that explore that area will discover the remnants of an old homestead site on higher, drier ground. Moving further east along the trail, the casual observer will realize that the understory changes significantly with wetland grasses replacing the robust blaeberry and cowberry understory, in reaction to the increasingly wet ground underfoot. Further along the (raised and dry) trail, there are two spots where small open streams are first heard, then seen. These wet/dry transitions do two things. They provide a gradation of microhabitats that support a range of species. But they also provide an aesthetic complexity, which rewards the eye and ear, the nose and the kinesthetic (bodily) senses of those that walk attentively through this amazing forest. The east-west route through the eastern edge of the forest reveals more wet-dry transitions that can be appreciated from a dry trail.

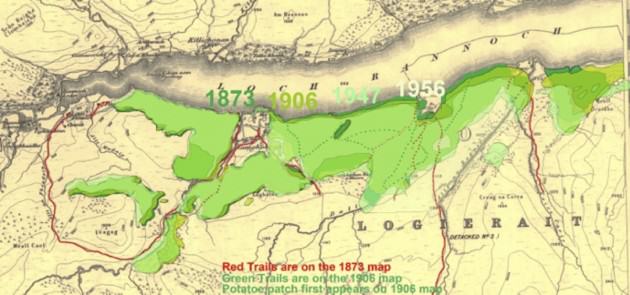

To understand the Black Wood one has to grasp the past, present and future in terms of the 300-year life cycle of a Scots pine tree and its relationship to the use of the land across that period of time. In the historical map above we can see an overlay of edge-to-edge mixed ancient semi-natural forest cover in 1873, 1906, 1947 and 1956; represented through color transparencies. The map tells us three important things. First the Black Wood has been resilient over this period of time, and regenerates despite losses. It establishes that some trails existed prior to 1873, while others were not mapped until 1906. Finally the dark spot at the centre of the forest, an area known as the ‘potato patch’ (by locals and the Forestry Commission ecologist), and attributed to war-related food production in the first part of the twentieth century, was actually cleared by 1906, apparently for some other purpose. The potato patch is notable today for its broad stand of commonly aged trees that reads like a plantation, straight and tall with little understory diversity. It provides an aesthetic counterpoint to the rest of the forest.

What we are trying to establish here is that the Black Wood is a powerful aesthetic presence. We argue that it ‘returns ones gaze’, or that it is woodland of sufficient complexity that it cannot be seen in a day, and indeed evolves in one’s eye and mind as it is visited over seasons and years. The Black Wood contains nested layers of wildlife, plant and microbiological diversity, that starts with the topography and soils, which are then followed by understory plant life, and a wide age-range of trees, some that are less than 100 years old, some that are more than 250 years old. In the layers of organisms, divergent reproduction cycles and ever-changing seasonal conditions lies a complex aesthetic experience that repays attention over time. But what is important here is this is a form that emerges from three centuries of conflict, beginning with the Jacobite rebellion and the forfeiture of the land in 1692, 1715 and again in 1745. In the middle of the 18th century, experiments with sheep would displace people as half the population was forced off the land in Rannoch Glen. Experiments with deer fenced into the forest would further shape the form, as would the eradication of the Gaelic language, which was still dominant in the decade before the dawn of the nineteenth century, and largely lost by the 1960’s and 1970’s. The dominant hill in the area is Schiehallion, or Sìdh Chailleann the fairy mountain of the Caledonians.

In a recent publication the Edinburgh Landscape Architect John Murray explores the contemporary value and import of the Gaelic language and its relationship to landscape; he talks about ‘ground truthing’ the biotic and the cultural. He says, “…at a fundamental level, the landscape is composed of physical, biological, and cultural elements.” But he also argues that landscape is imaginary and “…shaped in part by our perception and the values prevailing in society and cultures at the time” (Murray 2014, p. 208). Considering Gaelic place names, Murray reveals the fundamental interdisciplinarity that is embedded in knowing a place on foot and in the refinement that emerges during the exchange of everyday life. This is the model of experience and knowing that I want to consider in closing.

With any talk of the future, it is essential to recognize the past. With any talk of urban nature, we must reference the exurban. It has not always been clear that the ancient semi-natural forests of Scotland would survive the industrial age. It is only recently that conservation interests have been able to establish policies and regulations that protect these ancient forests from the mischief of owners, managers and developers. The question that remains unanswered is what can be done to kick start the social and cultural ecologies of places like the Black Wood? How can we create new cultural interface to essential ancient exurban forests and how do win turn, develop meaningful urban forests that reference the larger cultural import of nature? Ultimately, can art and culture serve the long-term interests of the complex of inter-relational living organisms that are Black Wood? I don’t think the problem can be resolved by catalytic agency, I do think the problem may yield to diverse and sustained creative inquiry.

For more information see collinsandgoto.com also please visit, anthroposcenemanifesto.com

about the writer

Emilio Fantin

Emilio Fantin is an artist working in Italy on multidisciplinary research. He teaches at the Politecnico, Architecture, University of Milan, and acts as coordinator of the “Osservatorio Public Art”.

Emilio Fantin

What role does art play in society? What cause does it serve, and why? Let us consider artistic process but also the practice of art in public spaces. Artists working in urban public spaces, or in natural contexts, have an innately different approach from those work in the solitude of private studios. The latter group conceives and realizes works of art work by establishing a bilateral relationship with the canvas (or its equivalent). The inspiration of artists working in this way flows freely from their interiority onto the canvas without being disturbed or modified by the neutral context of the studio. No word or gesture interferes with it. But artists working in public spaces must deal with an array of diverse and uncontrolled quantities—with the agency of people, environment, soil, pollution, the weather and so on. The work is the result of a confluence and a collaboration with external elements that ipso facto imply an interdisciplinary approach. The artist must transcend ordinary boundaries of the discipline in order that his inspiration is not disturbed, but infused and elevated by the externalities of the context in which he or she is working. The circumstances in which the art of public spaces is generated must be assumed by the actuality and vitality of the artistic process if the external, physical world is to be rendered internal and a part of the work. For it is not possible have a sincere relationship with the “external” if the profound quality that links any being to the soil, to the trees, to the city, is unacknowledged. The analytic psychologist James Hillman says that places have a soul. He does not mean, by this, that places are solely defined by their historical, geographical and social characteristics but that each has a further and distinctive essence. Particular places have special qualities so that, for instance, churches and places of worship are frequently built upon themselves—in the same places—century after century. What is in evidence, here, is the correlation of the soul of the place and the purpose of the Church. Thus if I am invited to intervene in an urban or ‘green’ space then it is incumbent upon me to engage with the context of the place. Listening to the voices of the trees, the soil, and the people inhabiting a space is the sine qua non of the creation of meaningful art in public spaces. The recognition and respect of the essence of natural elements is what allows an artist to properly feel and integrate the soul of a place. So, in an urban context, “to see” is to capture the essence of a place through its atmosphere; it is to learn it through the messages and indices of the past, but also the future, that its architecture communicates. To “feel” the history and social configuration of a place is to read across its colors and geometrical forms. Only after having interjected himself into the soul of a place, is the artist able to act. Without compromising the inspiration or integrity of the work, its essence emerges. And as a consequence, whoever looks upon the installation or experiences the intervention will recognize in his or her very being, the inherent quality of the place. This raises awareness. I guess we can call “art,” anything that is able to consolidate the deep legacy of the soul of the place, or that supports the imaginary that emanates from it. Art is work that provides momentum to the humblest invention without prejudice.

about the writer

Lloyd Godman

Lloyd Godman is one of a new breed of environmental artists whose work is directly influencing 'green' building design

Lloyd Godman

As a passionate gardener and photo-based artist in 1996 I made the connection that plants are actually a form of photography; both use the magical, mysterious ingredient that is LIGHT! In fact, the largest photosensitive emulsion we know of is the planet earth. As vegetation grows, dies back, changes colour with the seasons, the “photographic image” that is our planet alters. Increasingly human intervention plays a larger role in transforming the image of the globe we inhabit. Imagine foliated land as a photo-sensor (like a digital camera) that responds to light speeding past the planet. When we remove vegetation and replace it with buildings and infrastructure like roads, as in our cities, the materiality of the building becomes a “dead pixel” in the living sensor of the planet.

So in 1996, I began by growing images into the leaves of wide leaved Bromeliad plants and quickly the work evolved into complex interactive installations of Bromeliads suspended from the ceiling of galleries. Through studying the unique biology of these amazing plants I came to realize how they could adapt to the harsh conditions of a gallery’s air con system. I came to realize that using living plants in or as art transcends art as environmental comment and becomes art as an environmental action. In this I was inspired by Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks – City Forestation Instead of City Administration, 1982 and set about to explore ‘art as active solution.’

Supported through a City of Melbourne Arts Grants 2013, Airborne was an acid test installed for 14 months in central Melbourne with no soil or auxiliary watering system. The work consisted of 8 suspended rotating air plant sculptures and withstood prolonged periods of dry and record heat, opening a portal for a new space plants could occupy in the built environment beyond the, roof top, beyond the vertical garden in what I termed Alpha Space.

As Bromeliads (Tillandsia is a Genus within the family) grow asexually, the living art works are super-sustainable, that is over time they can be harvested to provide a bio-resource to create new works. Unlike other artforms which often create more dead pixels in order to present their sustainable themed art, this super-sustainability is one of the truly unique characteristics of creating art with plants, and is especially so with Tillandsias.

As a means of retaining moisture, the highly evolved biology of Tillandasia uses a double photosynthetic pathway, capturing CO2 and releasing oxygen at night. They use tiny silver light reflecting trichome cells to absorb all water and nutrients through the leaf and can actually uptake heavy metals from the urban atmosphere.

At present I am carrying out an experiment with Tillandsia installed on four sites on Eureka Tower, the second tallest building in Australia at levels 56, 65, 91 and 92. If the experiment proves successful a larger project is planned which will open the way for installing plants in a creative but effective manner on super high-rise buildings.

Through the direct use of appropriate plants in their work, artists have the potential to occupy the largest of gallery walls and spaces in both a permanent and super-sustainable way, reach the widest possible audience and effect real change in the urban habitat. The walls, roofs and “alpha spaces” of our cites are the blank canvas of the 21st century, these are the spaces we must invade with our ideas and living green medium. Plants are a new (old) medium and one we must begin to use more often. By assisting plants to colonize the bare surfaces that are our buildings and the sky space between them in an imaginative manner, contemporary artists can evolve a blue print of urban nature and green spaces as fundamental as the discovery of single point perspective. If we turn to art action, future generations will experience this next millennium in a sustainably positive manner.

about the writer

Julie Goodness

Julie Goodness has a PhD in Sustainability Science from the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University; her research is focused on urban social-ecological systems, functional traits and ecosystem services, environmental education, design-thinking and design-based learning, social action and community development.

Julie Goodness

I can still recall my first encounters with street art when I became a New York City resident; these small urban interventions of images or words always seemed like a personal entreaty, an invitation to reengage with an urban fabric made momentarily unfamiliar. I am still struck by the unique energy they generated within me; there was a sudden flash of inspiration to think differently about my role in the city or even take some kind of alternative action. Indeed, as Pippin Anderson details in this roundtable, I likewise think that urban graffiti and street art is one of the more provocative and universally accessible mediums through which we can engage our urban citizens.

Lately, I’ve grown interested in how to propagate this feeling of inspiration and rousing call to action that I’ve found so satisfactorily embodied in street art. How can we spur our fellow city residents to make their own creative expressions and entreaties about their hopes for the city? One interesting possibility is participatory art, in which people can interact with and/or add to an existing installation, or are provided with instruction and materials to become the makers themselves and carry out their own artistic ventures. This is by no means a new concept, and may range from collaborative murals to data-driven exchanges (a favorite New York City example is Amphibious Architecture, which communicated information about fish presence and water quality in the East and Bronx rivers via SMS conversation).

In my own exploratory attempt at participatory urban engagement, this year my colleague Katie Hawkes and I designed and pioneered Youth Design Studio, a sustainable design class for high school students that leads them through the process of how to research, design, and build projects for their community.

Hosted with groups of students in Cape Town, South Africa, the class was a project of the 2014 Cape Town World Design Capital, a year-long programme dedicated to exploring design as a medium for creative social transformation.

One of our lessons was a hands-on introduction to photography, in which we taught basic technical skills and demonstrated how the artistic medium could be used as a communication and storytelling tool. An ambition to have our students document the challenges in their communities (and therefore begin to explore their visions for possible creative intervention projects), led us to take a step back and give a more straightforward assignment:

Tell the story of your day-to-day life through the people, places, and things that are important to you.

What came back to us was truly powerful: beautifully composed images of family, friends, and objects of importance, but also very interesting depictions of connection to the urban nature of the city: the beach and ocean waves captured through a window of the schoolbus, or the sunset over a wetland in the informal settlement. One of our students expressly told us that his photographs told the story of his connection to nature and township life; a photo of a plant springing from a concrete wall (with the student’s shoe captured in the edge of the frame) spoke both of personal strength and of unexpected green flourishing in even the most challenging of urban environments.

With another group, whose prompt was to convey how they felt when they summited Table Mountain in Cape Town on their camp trip, we received images of both victorious exaltation atop tree stumps, and quiet peacefulness nestled amongst vegetation.

While this exercise with our students just began to scratch the surface of what kind of stories they could tell through photography, it was an important proof of concept: even our youngest urban residents can use artistic expression to articulate important parts of their identity, and connection to both people and places in their community. While our students’ images do not explicitly advocate for urban nature and green space, I think they demonstrate the great potential available when we’re given the tools to convey what’s important to us in our urban worlds. I would argue that the first step towards raising awareness, support and momentum for urban nature will start with broader opportunities to equip and empower urban citizens with the tools (particularly artistic ones) to figure out who we are and probe our relationship/connection(s) to our urban environment. It is only through the critical reflection process involved these artistic explorations that we may eventually be inspired to become advocates and perhaps find new ways to communicate our visions for future cities of social and ecological well-being.

Thanks to the learners at Ikamva Youth Makhaza Branch, Muizenberg High School, and Beyond Expectations Environmental Program (BEEP), who shared their experiences through photography!

about the writer

Noel Hefele

Noel Hefele is an ecological artist who paints landscapes as entangled shared places. He lives in Brooklyn.

Noel Hefele

I find the terms urban nature and green space to be fluid and amorphous. I think the issue is our cultural relationship to nature (in ourselves, streets, buildings, parks, books, and minds) and not necessarily thinking of pockets of green space within urban cities. The boundaries of these terms leak and interact with culture in inextricably intertwined ways. Art definitely contributes to the values, aesthetics and interpretations of such cultural relationships to nature, yet perhaps the question should be flipped—How can we pay more attention and value the ways art supports, awakens, expands and challenges our relationship to nature?

I paint landscapes. Cezanne claimed that “The landscape thinks itself in me and I am its consciousness”, suggesting a temporary merging of subject and object. A painting then becomes more of a collaboration than a representation of the landscape; it does not claim to speak for it, rather, the landscape almost speaks through the artist, giving a visual form to the intangible connections between people and place. Painting is a response to a perceptual experience of encountering a landscape and making it visible through the body.

This appeals to me because it resists further objectification of landscapes and the inherent life and agency of non-human worlds. It opens up lines of participation for these landscapes to enter our cultural ecologies, almost like a tree branch or root growing more complex over time if successful, or dying if not.

Art has no measurable singular end goal; it creates multiplicities of experience and interpretation. It can push at the boundaries of our ideologies. A painting can teach new ways of seeing or what not what to see. A successful artwork can enter the vital flows of a cultural landscape, often seemingly taking on a life of its own, growing and changing over time. Catalysts do not seem to be afforded that same vitality; they are more utilitarian, while art seems to blossom into the world.

I learn as my paintings “find their way”, moving through and highlighting aspects of a previously unseen social fabric as people respond to them. Sometimes people share personal experiences of places I paint, adding depth and richness to my understanding of the landscape. It allows me a degree of awareness and access to a web of relationships that constitute a place. It is a folding in to the cultural and natural landscape that is both humbling and empowering. I paint landscapes that I inhabit and explore as a process of inquiry, never as an authority advocating for nature from a position of expertise.

Urban nature and green space (and Nature, for that matter) are terms defined by the cultural frame we put around them. My painting practice has taught me that the valuable aspects of such places come from tangled knots of perceptions and experience, human and non-human that constitute them.

I am interested in art that can contribute to the development of an ecological aesthetic of connectedness, social responsibility and perceptual tuning to environment. My hope for my own work is that painting and exhibiting landscapes I live in can foster a sense of connectedness within a whole, enhance a sense of place and intimacy, and call to attention a larger web of relations that we live in and among.

All of our interactions with nature are mediated through a cultural lens or transactional membrane. Work within any discipline that chooses to focus on nature or the more-than-human world contributes to the shape, scope and sensitivity of that membrane.

Returning to the question, one way to answer is for artists to recognize that the dominant issue of our time is climate change and all work is produced in relationship to that. But the question can never be answered in full—there is no direct cause and effect.

I frequently walk past a remarkable 142 year old Camperdown Elm in Prospect Park. It is a gnarled, horizontally growing, weeping tree encircled by a fence and held up in places with cables and various support structures. A plaque states that Marianne Moore, a Pulitzer Prize winning poet, captured the public’s attention by immortalizing the tree in a poem. “Moore’s efforts and those of a concerned group of local citizens succeeded in increasing public awareness about threatened and vulnerable elements throughout the park.” I’ve always held the impression that the poem saved the tree.

Is the tree nature, culture, or both? Unique conditions created the poem and the poems reception played a role in saving this tree. The emergent Friends of the Park organization had a role, the Camperdown’s resistance to Dutch Elm Disease also played a role; a series of disparate yet confluent actions all deliver this tree into the present. Perhaps the poem was a catalyst of sorts, taking advantage of a perfect set of conditions to make a difference and raise awareness for this curious tree. And yet, the tree, created through grafting and unable to reproduce on its own, was already dependent on culture for its very existence.

Art can create ( gather and express) a sense of alternate value and aesthetic appreciation for nature and our lived experience in the world. Culture permeates our landscape—we are in and of this world. When dominant value is monetary and context is climate change, the argument for the scientific, the practical, and the engineered necessitate answers from the arts and humanities who focus upon perception and value.

about the writer

Todd Lester

Todd Lester is an artist and cultural producer. He has worked in leadership, advocacy and strategic planning roles at Global Arts Corps, Reporters sans frontiers, and Astraea Lesbian Justice Foundation. He founded freeDimensional and Lanchonete.org—a new project focused on daily life in the center of São Paulo.

Todd Lester

Artists cultivating food systems

When I’m asked how Lanchonete.org is art by a curator, I often feel like it’s a test to see whether I’ll reference Gordon Matta-Clark’s FOOD, a restaurant the artist/ architect and colleagues started in lower Manhattan in the 1970. Sometimes I start my response with what differentiates Lanchonete.org from FOOD, or share the variety of influences—from French cooperative bistros to Welsh pubs, from Fast & French in Charleston, South Carolina made by artists, JEMAGWGA to the 70s Lanchonarte project by Brazilian collective, Equipe 3—that inform and inspire the making of Lanchonete.org. When folks from outside the art world ask the same question, I’m excited … excited to share these examples but also because the project’s personality and aspirations reach into a range of spaces and co-mingle with everyday life. While we are making the container, what happens in that space, and on the broader platform, can be authored by anyone, artist or not.

Lanchonete.org is the evolving, materializing result of both my artistic practice—one that is both research-based and curious about organizational form—and a process of community organizing by a group of diverse stakeholders, that includes artists yet not as a majority. This dual persona is what makes Lanchonete.org such a dynamic process, and I actually love how it doesn’t have to be understood as art by everyone who encounters it.

Given the topic of urban nature and green spaces, I immediately think of the urban sprawl and congestion of São Paulo, and how the municipal electric company, ElectroPaulo, is the primary holder of remaining green space—the space under power lines—in the city. Lanchonete.org is a five-year project, and in the first two years, our focus is on developing strong partnerships from key sectors and populations, which we feel are foundational to the project. These include both GastroMotiva (culinary vocational training) and Cities Without Hunger (urban gardening), which partners with ElectroPaulo in the East part of São Paulo where unemployment is at the highest level in the city.

GastroMotiva trains at-risk, urban youth to cook and become chefs in professional kitchens. Cities Without Hunger teaches households how to grow produce in urban conditions provides both a healthy diet and income-generating opportunities. Cumulatively the gardens under Cities Without Hunger management produce at a surplus; therefore it is possible for a restaurant to buy directly from producers. It shares a very similar ethos with GastroMotiva, to first improve food preparation and dietary habits at the household level that, in turn, leads to employment opportunities and holistic betterment in families, communities, neighborhoods, business and the city.

We plan to purchase our produce from Cities Without Hunger and hire our restaurant staff from the ranks of GastroMotiva trainees. Furthermore, we have asked the founders of both organizations to be part of an advisory council for Lanchonete.org, and are planning a hybrid ownership model whereby their organizations can serve as anchors within the association’s membership if so desired. Both organizations (whose stakeholders are primarily from the periphery) have expressed an interest in having a central location—or food/food service lab—in the Centro for a variety of reasons; therefore, its makes sense to enter discussions with them now regarding future usage and management of the restaurant facility.

{ii}

As you might imagine, I’ve been thinking about food systems a lot since starting the Lanchonete.org project in São Paolo these past years. In the same period, a steady stream of stimuli started coming my way. Over a year ago, the Vera List Center for Art & Politics presented programming entitled Your food is on its way, that focused—in part—on food delivery workers in New York City and how online aggregating services, such as Seamless, can result in longer delivery routes by offering the customer more options yet do not encourage higher tips to the delivery person. So whereas the customer perceives improved services, the delivery people, often informal, immigrant laborers, suffer lower earnings.

A friend told me about the international peasants’ movement La Via Campesina and its Food Sovereignty Principles; and most recently Thiago, a Brazilian friend in NYC, recounted his trip to Queens to visit the office of Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International, and witnessed some police stopping a food vendor out front and throwing away her food. The food cart generally and Thiago’s experience specifically remind us that we live in a time when the very cultural (by which I mean broader than artistic/creative) reference for a commodity becomes illegal. We’ve seen food cart primacy (foodie hype, rodeos and other gimmicks) literally supplant the middle ground—and important space—of food workers and delivery person rights while at the far end of the agency spectrum, immigrants in Queens who depend on informal labor (selling food) as their sole income can have the product (and representation) of their labor literally destroyed. Food carts and other pop-up notions, of course, play into the speculative real estate (capitalist) force that influences many—even well-meaning—urban plans that give us the new green and pedestrian spaces in NYC’s higher income zones (e.g. Madison Square Park, Prospect Park) where the food carts are allowed, stationed, taxed and begin to atrophy (because in effect they lose their original mobility/flexibility when sequestered in these demarcated zones).

{iii}

I’ll stop here without attempting to fully compare and contrast the urban nature and green spaces of NYC and São Paulo. There are many commonalities and many differences, which I look forward to discussing. In the mean time, here’s a survey of projects—old and new that I’ve come across in my research:

{Projects by and with Artists}

- El Matam El Mish-masery (El restaurante no egipcio) (by Asunción Molinos Gordo).

- Vacant Acres Symposium (Meeting of land transformation advocates from all over the world by 596Acres)

- Taste of Freedom (by Felipe Cidade @ Art in Odd Places)

- El Internacional & Food Cultura Foundation (by Miralda)

- Acarajé + Gravura (by Thiago Goncalves)

- Doris Criolla (by Amilcar Packer)

- Foodshed (by Smack Mellon)

- Eat Art (by Daniel Spoerri)

- Guia san Pablo

{Places / Place Concepts}

{Canada Resource Guide}

- Plant Adoption, a project that relocated city plants from areas with a wealth of fauna to poorer neighbourhoods that are often neglected by the city (by Golboo Amani).

- Poster-Pocket Plants, a project that integrates nature into the urban setting by creating pockets in existing posters throughout the city to create spaces for plants to grow (by Shawn Martindale in collaboration with landscape architect named Eric Cheung).

- Outside the Planter Boxes, a project that focuses on transforming crumbling city planter boxes (by Shawn Martindale).

- A Campus Food Revolution at the University of Guelph (in edible TORONTO)

- Cities Feed Cities: Unearthing three unique urban agriculture projects in Montréal, Toronto, and Vancouver (in SPACING)

- Local Food Map – Guelph Wellington (tastereal.ca)

{NYC Resource Guide}

- Delivery City: New York and its working cyclists (film)

- Chinese Staff and Workers Association

- National Mobilization Against Sweatshops

- New York Communities for Change

- Restaurant Opportunities Center

- Fast Food Forward

{Misc / Projects / Organizations / Initiatives / Articles}

- Sustainable Food Systems (Topos Partnership)

- Street Vendor Project (Urban Justice Center)

- Pesticide Action Network of North America

- Sustainable Development Institute (Liberia)

- World Botanical Research Associates

- Politics of Food (by Delfina Foundation)

- Organic Consumer’s Association

- SEED: The Untold Story (film)

- Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance

- Hudson Valley Seed Library

- Fechado Para Jantar

- Seed Savers Exchange

- Center for Food Safety

- Iroquois Valley Farm

- Inspiration Kitchens

- Change Food

- Slow Food

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Patrick M Lydon

The lasting effects of an artist’s intuition and interactions

Two thoughts come to mind here. These thoughts likely stem from my getting to know artists who have such practices as I develop my own, and from my serving as an Arts Commissioner for the city of San Jose a few years ago, where public art commissions were large, and typically aligned with either ecology or technology as a theme.

The first thought is regarding the role of intuition, and the second is a note on materiality.

Most artists are likely to tell you that when they approach their work, they are not in a state of rational thought, but something we might call ‘intuitive’ thought—intuition is actually a rather poor word for it, but it is the closest most have come in the Western vocabulary.

The meaning of ‘intuition’ for me here, is one of place, earth, and spirit being connected well enough to serve as a primary guide for one’s actions. The luck of the artist’s position—and at times the curse as well—is that they tend to work in this intuitive state of mind as a matter of habit.

It is in this state of mind that the artist, as well the ecologist, the city planner, and others who seek to be truthful to their position as living beings on this earth, can meet and take deep and meaningful action together. This sentiment underscores a general need for development of an ecologically-connected mindset, for everyone.

So how does this help us create nature-awareness-catalyzing art? A primary application would be helping those who are involved in the propagation of a city’s structure—or in patronage of arts within this structure—to see the innate connection between an artist’s socio-ecological intuition, and the development of a vibrant nature-connected city.

Connected to this first point, is the rather difficult process of ridding ourselves of a very constricting requirement we often press to the artist, the requirement that they produce a physical icon.

Of course a great sculptural work situated well can fuel wonderment, connection, and intense depth in our experience of the nature and city which surrounds it, and it can be a catalyst in its own right. The work of James Turrell and his “Skyspace,” such as the urban situated “Twilight Epiphany” in Houston reverberate in my mind here as beautiful, meditative works which help connect us to this expanded consciousness.

Yet, in the shadow of such works, I believe it is critically important to also recognize—especially if we are to be mindful of nature and ecological working habits—that physical pieces needn’t always be case and point for urban art. Works such as the “3 Rivers, 2nd Nature” by Tim and Reiko Goto-Collins provide such an example in their use of community involvement to transform long-term plans for a city’s ailing rivers. In my own experience during a residency last year in Japan, I assembled a team to create a requisite temporary installation, however I think we all considered the legacy of our work to be the forging of long-term relationships between regional sustainable farmers and local community members.

Cities have a need for artists who make it a part of their practice to be change-makers, artists who make it a part of their practice to respond to the city, to its people, and to its built and natural elements. There are artists on this very panel who are exemplars of this, and many more throughout the world from Suzanne Lacy to Newton and Helen Harrison.

If an artist’s intuition and interactions can plant seeds in our minds, then the true importance of the artists’ work may at times lie more in a legacy of actions within the community which grow, shoot, and blossom from these seeds, rather than a tombic legacy of a finished art piece they might leave behind.

about the writer

Elliott Maltby

Ms. Elliott Maltby, founding partner of thread collective, definer of the urban backstage, iLAND board member, lover of novel landscapes, fisherwoman.

Elliott Maltby

In the light of the latest dire UN climate change report, perhaps we should be asking how art can catalyze and be action ; dramatic change in human behavior and our relationship to the environment is a necessity at this point. It should not be the role of the arts to simply weave a more compelling story with the facts that science provides, though there remains a need for that as well. But it is clear that knowledge and awareness alone do not serve as sufficient catalysts for change. I definitely don’t pretend to have the answers, but here a few ideas from my work with thread collective and iLAND*:

collaboration

At its core, the field of urban ecology is multidisciplinary; art can take advantage of this rich condition, developing new ways of researching, communicating, and exploring solutions. Over the years iLAND has developed a specific approach to collaboration across disciplines, rooted in the practices of dance and kinetic understanding. Bringing together movement artists and scientists, visual artists and designers for an intensive two week residency to explore an aspect of New York City’s urban ecology, we support the intersection and invention of different modes of knowledge. Over the years. we have created an adaptable framework for collaborators to participate in each other’s methodologies—and further, to develop new hybrid practices and research strategies that are locally calibrated. Some of the most profound insights have emerged from instances when an expert in one field allows themselves fully the experience of being a beginner in another. This mode of working also breaks down specific hierarchies of knowledge and allows for tremendous cross fertilization.

Deep collaboration requires risk, and the willingness to inhabit odd and unfamiliar situations. This can lead to entanglements, frustrating [but ultimately productive] miscommunications, and slow progress, among other ostensible barriers, but it is the moving out of these entanglements that a creative realignment can happen. Collaborations of this type allow artists to develop new complex processes and research approaches to match the complexity of urban systems and dynamics.

embodied participation

There are very few spaces in our culture where developing new, or experimenting with, collaborative processes is the primary focus of research. iLAND residencies are not structured around the production of a performance, but are required to have a public engagement component. This can take many forms, but must have a kinetic or embodied aspect, and often actively folds public participation into the on-site research. And here is one of many places where my work as a landscape architect and my collaboration with dancers intersects—a strong belief in the power of the physical experience. The body has an intelligence of its own, one that both supports and contradicts cerebral understanding. thread collective’s recent proposal, Gowanus Field Stations, is an exploration of the ecology of the canal, through temporary public space installations dispersed along its length. Each field station creates a dedicated space for people to observe and engage with a distinct aspect of the canal: these discrete experiences create a shifting, composite, and embodied understanding of the area, and demonstrate the intermingling of human and natural systems.

the mysterious

Admittedly, mystery is an odd word in this context, and while I’ve looked around for an alternative, I haven’t yet found one. I want to posit mystery as a counterbalance to the didactic impulse that drives some art in the realm of urban ecology. I am captivated by art that transforms the familiar into the unexpected, and where there are intentional, intellectual spaces, gaps, and fissures for the audience to occupy and explore. Like embodied participation, these kinds of ambiguities allow for critical engagement and the construction of understanding, rather than simple reception of information, that I believe is necessary for action. And while there is much compelling research out there to share with a wider audience, access to information may be less of a challenge than the problems associated with too much information. Art can also uniquely address what is not known, or poorly understood, in relation to our environment—and in doing so, remind us of the limits and fallibility of our knowledge.

* I have also worked with Mary Miss, a panelist in this roundtable, on a number of iterations of her City as Living Lab. I defer to her to describe the successes and insights of this incredible project.

about the writer

Mary Miss

Mary Miss has reshaped the boundaries between sculpture, architecture, landscape design, and installation art by articulating a vision of the public sphere where it is possible for an artist to address the issues of our time. She has developed the "City as Living Lab", a framework for making issues of sustainability tangible through collaboration and the arts.

Mary Miss

City as Living Laboratory (CaLL), is a national initiative that we have spearheaded to establish a platform for artists, working in collaboration with scientists, urban planners, policy makers, and the public, to make SUSTAINABILITY TANGIBLE THROUGH the ARTS. CaLL asks: by what means can we foster roles for artists and designers to shape and bring attention to the pressing environmental issues of our time?

CaLL’s aim is to advance public understanding of the natural systems and infrastructure that support life in the city. Its strategies are grounded in place-based experience that make sustainability personal, visceral, tangible, and encourages citizen and governmental action. Ultimately, CaLL’s goal is to establish a FRAMEWORK that can nurture such multidiscipline and multi-layered teams in processes that bring about greater environmental awareness and envision more livable cities of sustenance.

This FRAMEWORK is a process of inquiry and exchange between artists and designers, research scientists, municipal policy makers, local community groups, and academic partners. Activating the FRAMEWORK are projects and programs that seed sites, with installations, interactive activities, and events. While focused on the unique conditions of specific locales, the projects and programs are designed to set examples that can extend to other cities over time. These activities are conceived to nurture partnerships among disciplines, institutions, neighborhoods, and interested individuals as they work together toward shared environmental and sustainability goals.

This FRAMEWORK is a process of inquiry and exchange between artists and designers, research scientists, municipal policy makers, local community groups, and academic partners. Activating the FRAMEWORK are projects and programs that seed sites, with installations, interactive activities, and events. While focused on the unique conditions of specific locales, the projects and programs are designed to set examples that can extend to other cities over time. These activities are conceived to nurture partnerships among disciplines, institutions, neighborhoods, and interested individuals as they work together toward shared environmental and sustainability goals.

There are two major facets to CaLL. One is the continued development of PRECEDENTS by Mary Miss such as FLOW (2009–2013) and Stream/Lines in Indianapolis (2013-2016), and If Only the City Could Speak in Long Island City, NY (2011-12), and the ongoing Broadway: 1000 Steps. The second is the support of PROGRAMS that promote collaborations by other artist/scientist teams. This is done by identifying an artist’s interests and recruiting an appropriate science (or other expert) partner.

One strategy CaLL uses to advance these collaborations is its signature WALKS where teams engage the public in a dialogue that makes real conditions—past and present—along with speculative ideas for future visceral and tangible through place-based experience. Building on critical concerns that have emerged from its research and outreach for the Broadway project, CALL WALKS invite artists to respond to features and issues along the avenue through place-based dialogues. The outcomes of these walking dialogues are contextualized in panel presentations that include outside experts and observers and are hosted by collaborating institutions.

The WALKS start with an invitation to an artist or designer to consider a site or location and an issue of distinctive relevance to that site. Once an area of focus has been determined, CaLL works with the artist to find a scientist or expert who can provide a new set of resources—data, methodologies, learning goals, perspectives, applications, etc. The artist-scientist team is tasked to reflect on the appointed issues in public spaces, exactly where their ideas might help increase awareness and accelerate change. This phase of the challenge is purposefully set in places that are accessible and open to all. The initial artist and designer-led WALKS have engendered dynamic exchanges and sparked innovative strategies. The WALKS have been developed as both an interactive public engagement, as well as a means to vet long-term partnerships between artist and scientist team members.

Other steps include nurturing ideas generated by the WALKS or forwarded in community WORKSHOPS, and the commissioning of full-scale PROPOSALS or PROTOTYPES. The WORKSHOPS involve a selected number of artists and scientists who have participated in the WALKS. They are designed to generate ideas and tactics for innovation and change that emerge from community responses and reflections, while building a grass roots support base, for proposed projects.

The development of these PROPOSALS into PROJECTS to be incrementally implemented and to make new ideas about sustainability available in communities at street level as is at the heart of this initiative. The goal is that through these experimental methods, CaLL is building a replicable practice that sparks dialogue and promotes action for sustainable urban life through art/science/community collaboration.

about the writer

Lorenza Perelli

Lorenza Perelli is an art historian, writer and artist living in Chicago. She taught Public art At the University of Architecture in Milan, with the artist Emilio Fantin. She is the author of "Public Art. Arte, interazione e progetto urbano", edited by Franco Angeli in Milano.

Lorenza Perelli

Do it yourself

The projects I discuss here are part of the recent debate on how art, architecture and design raise awareness to urban and natural habitat. They all are radical in the intention to foster a new reconciliation between nature, the city and the people who inhabits them. Abandoning the opposition between the nature and the city—heritance of some part of the ‘900 art and culture with its nostalgic theme of the ‘return to nature’—these projects work to bridge the human and natural habitats under the aim to make them more sustainable, accessible, and inclusive.