about the writer

Doreen Adengo

Doreen Adengo is the principal of Adengo Architects, an architecture and urbanism practice grounded in research and multidisciplinary collaboration.

Doreen Adengo

For most of my career as an Architect, I’ve taught part-time while I worked in an office. And as a result, I am interested in the interaction between theory and practice. This past summer I taught a Housing Studio at Makerere University’s College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology, located in Kampala, Uganda. The course was part of the university’s practical training program, in which we had a real client, a developer interested in building affordable homes on a 66-acre piece land about 25Km outside of Kampala. The team was multidisciplinary, involving five architecture students from the local university and two international affairs students from The New School, New York, which allowed for a rich and extremely creative design process. On our first visit to the site we found that 11-acres of the land was a wetland—meaning there was a seasonal stream in middle of the land, with two hills on either side. Our main challenge became exploring ways to incorporate the wetlands into the master plan as an essential part of the urban ecology. Inherently, the most challenging task at hand was to convince the developer not to destroy the wetland by filling it with sand and building on it, which is a common practice in Kampala, but rather to see it as an amenity and something that would add value the housing development.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: Kampala was built on seven hills, adjacent to Lake Victoria. These hills were once lush woods serving as hunting grounds for the King of Buganda, before being transformed, under British colonial rule, into a modern city. In 1945, the British colonial authorities hired the German modernist planner Ernst May to work on an urban plan of the then rapidly expanding Kampala city. The colonial urban planner used the ‘Garden City plan’ as the theoretical framework around which to organize elements of the city. The Garden City movement, as proposed by Ebenezer Howard in 1898, was an approach to urban planning in which towns of limited size would be planned and surrounded by a ‘green belt’ of agricultural land. This new plan was to allow for a doubling of the Kampala’s population to about 50,000.

In a way, the original plan for Kampala took into account the natural landscape and topography, in that each hill became its own ‘satellite city’ surrounded by a green belt of the naturally occurring wetlands. Kampala is right next to Lake Victoria, and the wetlands create a natural filtration system for runoff water as it goes into the lake. It’s therefore really important to respect the wetlands and not encroach on them.

KAMPALA TODAY: Unfortunately what’s happening in Kampala today, because of the growing population, is that people are starting to build structures in the wetlands and disrupting the natural filtration process. Kampala currently has a population of over 3 million people and accounts for over sixty percent of Uganda’s GDP. According to the Kampala City Council Authority (KCCA), Uganda is experiencing a high rate of urbanization averaging 5.6% per year. Currently, because of poor drainage, there is erosion of the roads and flooding. And because the slums are typically located at the bottom of the hill, the inhabitants experience harsh living conditions during the rainy season and are vulnerable to health risks. There is a separation of classes, with the upper and middle class occupying the top of the hills, while the growing urban poor occupy the bottom of the hills and encroach on the wetlands. These are issues that are difficult to tackle separately, because they are all interrelated. And as a result, the city continues to sprawl as the population increases and people look for new areas to live.

Spreading awareness about understanding and managing urban ecosystem in Kampala is therefore an important and challenging task. What is specific to Kampala is that the issue of the wetlands is tied to the housing shortage that the city is currently facing. The government body NEMA (Natural Environmental Management Authority) that is actively involved in protecting the wetlands and evicting the encroachers, does not have an alternate solution, and so the cycle continues.

Therefore, an important question in the case of Kampala is, how does one provide the much-needed affordable housing in a way that is sustainable and in equilibrium with the surrounding ecosystems? One approach to tackling this question is to engage in multi-disciplinary approaches to learning and sharing knowledge, and to work in ways that integrate theory and practice.

about the writer

Adrina Bardekjian

Dr. Adrina C. Bardekjian is an urban forestry researcher, writer, educator and public speaker. She works with Tree Canada as Manager of Urban Forestry and Research Development. Her current academic research examines women's roles, experiences and gender equity in arboriculture and urban forestry. She is also an Adjunct Professor with Forestry at the University of Toronto.

Adrina Bardekjian

Narratives and creative collaborations for urban forest education

Much of my childhood was spent outside. My sister and I imagined fantastical storied landscapes and acted these out by playing in parks, running on trails and climbing trees. As children, we traveled frequently between Canada and Europe and lived in different cities across continents. With each move, we changed schools, met new friends, and learned different languages. The only constant in our lives was change and the perpetual flow of our existence and understandings of new beginnings and connections.

I became interested in urban ecologies and the ebb and flow of dynamic stories and their energies that traverse the cityscapes and greenspaces we call home. Urban ecosystems are complex and diverse networks of the human and non-human, the built and un-built, and multiple ways of knowing and producing knowledge are integral to holistic learning. Urban forests and tree places are essential learning environments with opportunities for using and uniting alternative models of education, community outreach and citizen engagement. Different ways of knowing and producing knowledge are becoming more widely accepted (and necessary) in urban forestry. Having a variety of learning tools stimulates various parts of our brains and resonates on different levels—intellectually and emotionally. It helps us shape our ideas better and with broader reflection and contributes to a healthy social ecology that influences more inclusive public policies, builds community ties, and fosters a creative culture of stewardship, effectively planning for more sustainable living communities on all levels. Three examples that are particularly meaningful to me are:

Developing policy

The Toronto Cancer Prevention Coalition’s Shade Policy Committee recently used digital storytelling through film and created a video, “Partners in Action”, about the 12-year journey to develop and implement the City of Toronto’s Shade Policy. These efforts were made possible by engaging a multi-disciplinary team of experts, concerned citizens, and community organizations.

Building community ties

In Ireland, Hawthorn trees are rooted in folklore and cultural tradition. This past summer, while traveling, I learned of a story where citizens mobilized with a local historian to save a Hawthorn tree from being demolished for a freeway.

Fostering stewardship

The Truth about Trees is documentary film series produced by a collection of community partners and the USDA Forest Service that is capturing community stories about trees across the United States (I believe we need this in Canada). The main objective of this project is to raise awareness about the importance of trees, both ecologically and socially.

Over the past ten years I have had the privilege of working as a consultant and researcher with diverse organizations and dedicated individuals. I am continually inspired by my colleagues and mentors who have striven to enhance awareness about urban forestry through their collaborations and initiatives across Canada and internationally. Through my work with Tree Canada and the Canadian Urban Forest Network, we are striving to engage communities across the country and provide much-needed infrastructure for greening communities. We are seeing more in urban forestry that students are driven by transdisciplinary and problem-based learning. Cultivation, curation and connectedness are a large part of this conversation; what people know and don’t know about urban greenspaces and urban ecosystem conservation is dependent on who is doing the teaching and ultimately who is framing and telling the story.

Narrative is integral to our work in urban forestry. It renders our own intellectualizing down to a personal level—if you tell someone a story, it resonates. Shared stories bring in the human dimension—about mentorship, giving youth a voice, making complex ideas simple and accessible. Ultimately, narrative propels the imagination to consider and problematize broader issues. In my own doctoral research, interviews with arborists revealed the desire for more apprenticeships due to knowledge being lost as seasoned practitioners leave the profession.

Exploring the connections between our physical and social urban forests through a creative learning commons empowers communities that their voices, both independent and collective, matter in urban forest issues. Alternative models of education in urban forestry, such as oral history, community art (as explored in the recent TNOC round table), and digital storytelling, are useful because they challenge us to move beyond our confines and comfort levels, and to continue our work more collaboratively, free of siloes and with a broader understanding of affect and emotional resonance and resilience.

about the writer

Sadia Butt Sadia Butt

Sadia Butt is a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Forestry at the University of Toronto, Canada. She has worked in urban forestry for the last 15 years as a practitioner, researcher and a volunteer in raising urban forest awareness through environmental education.

Sadia Butt

“For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them.”

― Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

We often hear that by doing, we learn. When watching students over a few hours of measuring trees in their schoolyard or planting trees for a climate change monitoring project I have seen transformations in knowledge, understanding and relationships. Through my work and volunteering with ACER, an environmental education group based in Mississauga, Ontario, that is headed by a dynamic educator, there have been many heartwarming sessions with students and teachers. The ACER team arrives at the school to impart a scientific protocol to measure trees in a given area. We provide the tools of the trade and the “why it is important to monitor for climate change” and “why these trees our important to the urban green infrastructure”, as well as, show the students how to collect, record and in turn share the data they produce. In some sessions, the children also plant a combination of trees and shrubs in climate change monitoring plots before they learn to measure…all in one day and in shifts of classes. Later, when these children and young adults (grade 6 to 12) produce a baseline database and maps, you can almost see the lights turn on in their heads and their pride in accomplishing something meaningful. Not only do they learn to use a spreadsheet and GIS (tables and maps for the younger students) but they collectively produce a visual graphic of the baseline information they have gathered to share online with students in their school and other schools.

This transformation of knowledge happens in a tactical and visual manner, as well as, with a profound understanding of the role of trees. In countless incidents, where initially young students are thrilled to be outside, while older grades include a mixture of reluctant part-takers and go-getters, all the students leave with an awareness of the trees, themselves and the space that we all take. They become attached to the trees they measured or planted, wanting to name them and to be able to return and nurture them. Many times, those students, too cool for caring, or portraying themselves as trouble makers show resistance to engaging, end up the most attached, wanting to name “my tree” and wanting to plant more trees, dig more holes and ask more questions. The learning leads to more doing!

Apart from the practical and technical information they learn, such as, digging with a shovel, mulching, watering, using tree mensuration tools, they are understanding how they are part of the group, part of nature and that they are woven into the collaborative task of monitoring nature. They become leaders, observers and teachers, further reinforcing the information we imparted as facilitators and even adding from their experiences. Students build intricate relationships with each other and trees through the planting and measuring activity and develop a sense of environmental ethics. In one incident non-participating students who vandalized planting plots were exposed by their peers, an unprecedented behaviour, for destroying their plots. These students were enraged that others would violate the freshly planted trees.

Thus, the way we learn and subsequently teach is an important aspect of how we gather knowledge to apply to our work tasks. Urban ecosystems being complex may require that those who have the responsibility to manage them need to engage in hands on training, work with the human and non-human actors that dwell in the space that we our trying to conserve and manage. Often knowledge is not understood or respected when the experience of it is minimal. It can be attributed to the lack of doing and the lack of opportunities to learn and share knowledge in an inclusive and holistic way.

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

Lindsay Campbell

The ‘science wars’ of the 1990s pitted positivist, quantitative, and realist science against qualitative, post-positivist, or critical approaches. These binaries have become all-too familiar. Some scholars claimed that social scientists suffered from “physics envy” as they tried to emulate methodological approaches from the natural sciences in order to enhance the validity of their claims. Others rejected these attempts and celebrated situated science, where subject and researcher are always already entangled.

Recently, a colleague of mine attended an interdisciplinary conference about humans and nature where the keynote speaker from the public health/active living field called case studies the “dregs” of research. This comment suggests the importance of large sample sizes, precise measurement, experimental design, and control groups to make claims that are scientifically “True” (with a capital T) to inform policy and design.

Clearly, these old lines in the sand are far from settled. Particularly in an era of big data and open data, numbers continue to talk. Quantification, metrics, benchmarks, and targets—these are the ways that ‘sound policymaking’ has come to be understood and framed. This is particularly so in the arena of sustainability planning, which—since the early days of Agenda 21—has emphasized setting and monitoring sustainability indicators as one of the key steps in policy change.

Yet, for all the attempts to be rational or scientific, policymaking is still a political process—and one that is carried out by thoroughly subjective humans. We are swayed by compelling storylines and important constituencies as much (or more so) than the numbers.

We can observe the confluence of these two strains (norms and numbers) shaping decision-making through case study research on the MillionTreesNYC campaign in New York City, where I live. For years, the NYC Parks Department meticulously collected data on the city’s urban forest. Working with researchers at the U.S. Forest Service (where I work), they calculated the ecosystem benefits of street trees. This argument made ‘business sense’ to former Mayor Bloomberg—and city agencies began working toward setting a citywide tree canopy coverage goal as part of PlaNYC2030—the city’s sustainability plan. Simultaneously and separately, Bette Midler, the entertainer and founder of the nonprofit greening group New York Restoration Project proclaimed that she wanted to “plant a million trees in the city”. This claim was rooted in a personal commitment to greening, particularly in underserved neighborhoods. Filled with a showperson’s flair—this goal was pure storyline. Midler reached the ear of City Hall decision-makers and was brought into the planning process. These two halves were woven together to create the MillionTreesNYC public-private partnership that made both scientific claims and normative arguments about the importance of greening. (The program, launched in 2007, has nearly completed the planting of one million trees citywide.)

So, what is the role for qualitative research—particularly the ‘case study’—in our current era of sustainability planning and green infrastructure initiatives? Qualitative methodologies are helpful for investigating processes and mechanisms, for constructing accounts of complex phenomena. While quantitative approaches can show statistical relationships very well, they are limited in their ability to theorize mechanisms. Case studies help us delve further into questions of how something is occurring. Reliance on numeric models obscures both the uncertainty behind their production and the value-laden decision-making in their deployment. Qualitative accounts help make these clear. They uncover the ways in which current modes of science and knowledge production are always already political: we wield our stats, maps, data, and models toward particular ends. Finally, some of our greatest pieces of knowledge about city planning, urban form, and history have been case studies, idiographic accounts of one person or one place—whether it be Jane Jacobs on New York City or William Cronon on Chicago. As cities continue to go through great transformations, including the growth of megacities, the shift from sanitary to sustainable, and responses to climate change, we need to continue our case study account of how these transformations occur.

Understanding complex social-ecological systems like cities requires interdisciplinary teams and many ways of knowing. These teams should span not only the traditionally called-for areas of social and biophysical sciences, but should bring in perspectives from the arts and humanities as well. We need all of our faculties, senses, thoughts, and feelings to understand (and then re-shape and re-define) our urban systems. The first step toward building these bridges is not to trod over the familiar terrain of the science wars, nor to denigrate one side as “dregs”, but to recognize the value and import of multiple approaches and to bring them into conversation with each other.

about the writer

Luke Drake

Luke Drake is an economic geographer who does action research related to urban agriculture.

Luke Drake

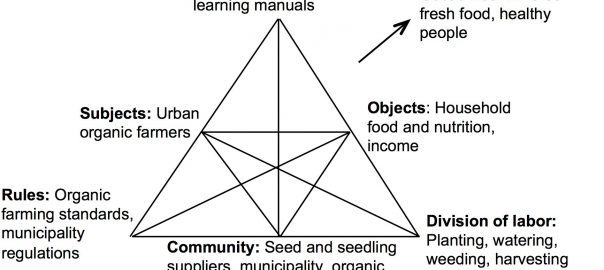

This past summer, a collaborative research project in Trenton, New Jersey (USA), examined how vacant and abandoned properties might be repurposed to increase healthy food access. The project emerged from the work of a Trenton-based non-governmental organization (NGO), Isles, Inc., to call attention to vacant properties and healthy food access. This project was based in the idea that the existing stock of vacant properties might, in various ways, contribute to a better food environment. Proposed solutions could include food production in community gardens and urban farms, as well as repurposing buildings into other food-related businesses. There was no comprehensive inventory of vacant properties, however. We started out with a few important questions. How many vacant properties are there, and where are they located? What would be the best areas or individual properties to target for food-related projects? What do residents want to see happen to those properties? This blog post focuses on the topic of vacancy, and the way that one’s definition of vacancy can affect the understanding and management of urban ecosystems.

With a diverse group of stakeholders—faculty and students from Rutgers University, NGO staff, and city planners—this project relied on different ways of thinking about urban space. Certainly, urban ecosystems are a complex web of social, built, and natural environments, and it became clear to us that different ways of knowing reveal parts that are otherwise hidden when using only one perspective. Take the term “vacant property”—it implies an empty space that is ready and available to be used by others. What is ready and available, however, is not universally understood. We encountered a range of ways to define vacancy in our study, and we saw how those definitions might be incompatible with each other. For those interested in food production, a community garden is already a thriving part of the city, and for the gardeners, it is indeed not vacant. Yet historically in the U.S. (and in countries across the world), these are often unsanctioned and informal sites, and local authorities have long assigned vacant status to such spaces. For local authorities interested in tax revenues and property values, construction is often preferred to something like community gardens as a long-term solution—although cities increasingly zone such spaces as green space or parks, and agriculture is entering zoning codes in some U.S. cities. An unmaintained lot with overgrowth of plants and weeds may be undesirable from both a food and planning perspective, but it may also represent a valuable site of biodiversity and urban habitat in an environmental science perspective. To clean up that site, whether for a garden or a building, potentially takes away that habitat. Furthermore, residents had transformed other so-called vacant lots into dynamic social spaces—using them as backyards and semi-public green space. These sites did not produce food or tax revenues, and the manicured lawns were likely not as biodiverse as an unmaintained lot; but they served important purposes for neighborhoods.

In a study to create an inventory of vacant properties, the choices of how to define vacancy carry ramifications for public agencies, neighborhood social dynamics, and natural environments. The recognition of multiple ways of knowing, however, is not necessarily cause for inaction. Questions posed by Danish geographer and planner Bent Flyvbjerg are helpful in this regard: where are we going, who gains and loses, is this development desirable, and what should we do about it? In our case, we began from the perspective that we should serve community needs, and therefore we did not want to classify those sites as vacant that were already serving those needs.

Bryce DuBois

I am steeped in a tradition of studying emotions and behaviors having been educated in the discipline of psychology. But I have turned away from the psychological tradition of describing behaviors and emotions from a normative perspective, and toward an environmental psychology perspective of the most interdisciplinary kind that is embedded in the places that I work in and write about. This is what my program at the CUNY Graduate Center calls a critical perspective, mostly because we ultimately have a desire to upend unequal power relations in places. In the management of urban ecosystems, I view unequal power relations as relating to questions of who has access to learn about and act upon what they have learned. For me, the most interesting sites where I can understand this affective experience and potential inequality is in urban public spaces, such as beaches. It is in these spaces where we can understand Henry Lefebvre’s suggestion that urban space reproduces and reifies social relations. An embodied approach stresses that people develop an understanding of places that are mediated by their physical body, and filtered through their affective experience and the society and culture where they live. In urban public spaces, these everyday experiences are often structured by politically motivated configurations that shape how people live in, interact with, and ultimately develop a relationship with these places. Therefore, an embodied approach can speak to power to make visible how everyday experiences are limited by the form of the material space, and the rules and ideas that construct what is appropriate in the space.

As an example, lets use surfers of the urban public beaches in New York City. Visits to these beaches are regulated to ensure the safety of the visiting public and the valued flora and fauna there. One example of this regulatory approach is that up until 2004 surfing was illegal at Rockaway Beach, because of a fear of letting people swim without the presence of a lifeguard. Since that time, surfers have been allotted two 2-block sections of the NYC parks’ 6.2-mile long beach where the bathymetry of the beach creates the best waves to surf on. In interviews that I conducted with surfers in Rockaway before Hurricane Sandy, they spoke of ecstatic experiences while surfing that included intense emotions such as love and fear. These experiences depend on sand and littoral drift to create preferable wave shapes when wave energy moves up the East Coast.

Therefore, it was a logical conclusion for surfers to restore the sand dunes that had been flattened by Hurricane Sandy to restore the wave shape that they loved. In the summer of 2013, Surfrider worked with the NYC parks department to rebuild dunes using Christmas trees.

Furthermore, Sandy highlighted how polluted the water can get because of combined sewer overflow, so Surfrider members have taken to testing water quality to ensure their own safety and to monitor progress on sewage treatment plant improvements throughout the calendar year. It is because of the affective experience of surfing that these surfers have become active in the governance of the Rockaway Beach ecosystem.

How people recreate plays a role in how people come to know and potentially love urban ecosystems. True not all people that surf become stewards of the dune ecosystem, but all surfers potentially embody a different type of knowledge about the beach than non-surfers. Thus, an embodied approach to the study of how people relate to places makes it possible to understand how people learn about and love urban places through their bodies, a love that is key to urban ecosystem governance.

about the writer

Johan Enqvist

Johan Enqvist is a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the African Climate and Development Initiative at University of Cape Town and Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University. He wants to know what makes people care.

Johan Enqvist

“In India, you can die from anything but boredom.” This tongue-in-cheek remark was delivered by an Indian man I had joined for a two-day trek in the Western Ghats. Maybe it is a common expression or maybe he was just trying to scare (or impress) me. But he did put the finger on something I came to realize several times in his country: there is always something new to experience, and there is always a different way of knowing it.

The Western Ghats is not only great for hiking but also the source of the Cauvery river, from which most of Bangalore’s water supply is drawn. It is pumped across 100 km and raised over 300 meters, at an immense cost for the city. Why is this needed?

Historically, a network of man-made lakes, or keres, dotted the landscape around Bangalore. Managed by nearby villages, the kere was crucial not only for drinking but also irrigation, domestic needs, religious ceremonies, and fishing. However, with the first connection to Cauvery in 1974 came a new era of rapid demographic, economic and environmental change. Forty years later, most lakes have dried up, been filled with polluted wastewater or simply converted into bus stations or cricket stadiums. Meanwhile, groundwater levels have plummeted and the city has reached the limit of what it can draw from Cauvery to support a population that has grown from less than two to almost ten million.

Framing this situation as a mere failure of lakes management is not telling the whole story. In the exponential growth of the city, every piece of land becomes valuable and the identity of water bodies is highly disputed. Are they traditional keres? Or obsolete pools of wastewater generating malaria and dengue fever? Or potential biodiversity hotspots with havens for birds, fish and amphibians? Or are they recreational spaces, best managed through private-public partnerships to the benefit of the modern city’s amusement economy? Or should they be converted into tanks in a new, decentralized water supply system?

All of these arguments have been made in Bangalore, and several water bodies have been modified to fit with the different ideals. Some citizens prefer idyllic landscaped lakes for their Sunday walks, while others’ livelihoods are crucially dependent on access to water for cattle rearing or open-air clothes washing businesses. There is potential conflict between fishermen and birdwatchers, between gated communities and migrant worker slums, between “localites” living in the area for generations and newcomer techies employed in the booming IT industry.

But amazingly, some inspiring success stories seem to avoid picking sides and instead embrace these differences. Drawing on the knowledge of birdwatchers to rebuild a functioning ecosystem, benefiting from the traditional fisherman’s trained “eyes on the water” for monitoring, acknowledging the traditional custom of idol immersion, and encouraging continued interaction with the restored lake through access for cattle herders and school children, the local community organization mobilizes a multitude of experiences, needs, and ways of knowing. By recreating an urban ecosystem that is intertwined with a broad set of users, legitimacy of the project is strengthened and more people have an interest protecting their common space.

These new bottom-up projects are not solving every problem. Although reports show returning groundwater near restored lakes, the city still faces large-scale water scarcity. But the achievements of these initiatives have motivated dozens of other neighborhood groups around the city to take up similar struggles. By embracing the different types of engagement, experiences, and expertise, Bangaloreans are demonstrating that diversity is not only a great antidote to boredom—it’s also a great asset in urban ecosystem management.

about the writer

Nate Gabriel

Nate Gabriel is an Assistant Lecturer at Rutgers University. His research is on the political ecology of urban parks and sustainability.

Nate Gabriel

For me, the question posed for this round table—“How can different ways of knowing…be useful for understanding and managing urban ecosystems”—begins with a historical question: How have ways of knowing influenced the management of urban ecosystems, and how have they integrated with particular ideas about the city itself? Understanding these histories and their consequences can, to paraphrase Michel Foucault, help to free us from what we silently think, and so enable us to think differently.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in urban commons. (For the sake of simplicity, I use the term commons to mean “open-access commons”, which are resources to which access is relatively open and free from restriction.) This trend dovetails with another movement toward thinking of cities as “socio-environmental” entities (rather than as strictly socio-economic ones), where environmental commons like air quality, water resources, and green space are seen as not merely supportive of urban functions, but fundamentally integrated into the urban fabric. This pairing has wide-ranging ramifications for how we interact with and reproduce our cities, since common resources have historically been seen as antithetical to the efficient functioning of cities, where privatization or tight government control have been seen as necessary solutions to potential overuse of resources.

In my research, I use urban green space as way of thinking through the ways urban commons are used and regulated. In the mid-19th century, cities in the United States (and elsewhere) became host to scores of large urban parks whose purpose was to provide sites of recreation for the growing working class. In addition to this important function, many urban parks were established as a means of protecting watersheds from industrial development, which had to some extent already begun to pollute vital water supplies. In these ways, parks were a reconfiguration of commons, direct responses to the anticipated free-for-all that would come with the industrialization of urban life.

On the other hand, parks also incorporated woodlands, farmlands, and open fields that were already under heavy use as de facto commons by urban people for a variety of household purposes (hunting, foraging and farming, logging, etc). Thus, the establishment of parks in the 19th century was also a form of enclosure that limited the range of purposes these spaces could serve for urban people, and was more than a simple matter of drawing borders to conserve undeveloped lands. After de facto common lands were reclaimed by city governments, urban people had to re-learn what they were meant to do with these lands, and that was a lesson that they did not take to readily. My research suggests that urban people have continued to use parks for food, medicine, and other economic purposes throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and into the 21st. (See here and here; also here.)

Nevertheless, such reconfigurations of commons remain a familiar feature of the urban landscape. For example, the Reading Viaduct, a once well-used elevated railway in Philadelphia, was abandoned in the 1990s. Since then, opportunistic organisms have been allowed to thrive there. Thistle, Ailanthus, wineberry, feral dogs and cats, and a few humans have made it their permanent home. Other humans living in homes adjacent to the viaduct have frequently (but illegally) used the site to escape the noisy, fast-paced city. But growing interest in such places, partially the result of the successes of New York City’s High Line and Paris’s Promenade plantée, have resulted in plans to convert the Reading Viaduct into Philadelphia’s own elevated rail park, which will dramatically remake the space into something more akin to other city parks—replacing unruly vines and edible weeds with benches and walking paths—privileging a narrow set of leisure-oriented activities at the expense of all others.

So, what difference would it make to think about urban commons differently? What would it mean to reimagine urban space itself as a commons? How would that change our managerial approach toward urban green space, biodiversity, water, air?

The start of an answer is to recognize that our approach to managing urban commons—for example, the institution of parks as recreational spaces—is a political act that reifies certain notions of the city, nature, and economy at the expense of others. The organization known as Fallen Fruit, which has articulated a vision of urban commons that incorporates edible landscapes, is one good example of an attempt to imagine urban space differently. But the point is that we are always making choices among possible alternatives is inevitable. The question is whether these choices are “silent”, in Foucault’s terms, or spoken so that everyone, including ourselves, can hear them.

about the writer

Tischa Muñoz-Erickson

Tischa A Muñoz-Erickson is a Research Social Scientist with the USDA Forest Service’s International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF) in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico.

Tischa A. Muñoz-Erickson

How cities think—this was the title of my doctoral dissertation. Not surprisingly, this title provoked a lot of mixed reactions. From those who view cities as physical infrastructures which cannot think, to those who view large social organizations and institutions as having the ability to generate collective thought or worldviews, and therefore the title was nothing groundbreaking. Then there were some that are part of the trend to create Smart cities and found the title to be attractive and intriguing.

Neither one of these views, however, reflected the intention for investigating how cities think. My goal was not to examine what cities think or how they think in a unified cognitive way per se, but rather on the social practices and networks that mediate how different ways of knowing urban systems can co-exist, interact, or conflict. To put it in the context of this blog discussion, I already assumed that different ways of knowing are useful and necessary to understanding and managing urban social-ecological systems. What intrigued me about investigating how cities think were the ways in which those different ‘knowledges’ were managed, integrated, shared, or utilized by different social actors, and therefore how these social relations underlying the production and use of knowledge influence how we envision and design urban systems. In other words, how ways of knowing may or may not be useful.

To illustrate, in the city of San Juan, Puerto Rico, I found that there were multiple types of knowledge, such as scientific, technical, local, and managerial, present and active in the network of actors (organizations) involved in land governance, thus showing potential for the inclusion and integration of diverse ways of knowing into urban ecosystem management. However, deeper analysis of how the network was configured, who the central actors were, and how this knowledge was communicated revealed that there were power asymmetries and fragmentations among actors that kept different ways of knowing from influencing or being used in governance. For instance, state level agencies that relied heavily on technocratic and bureaucratic ways of knowing still dominated the information available about land use and the management approaches towards land governance, even though recent institutional changes towards municipal autonomy demanded more local, bottom up management approaches and information. Thus, even when different ways of knowing existed and should have had the opportunity to influence political opinion and management, social relations and structures kept these alternative ‘knowledges’ from being useful.

My point is that different ways of knowing or of producing knowledge can be useful to the extent that social processes and networks allow their circulation, deliberation, negotiation, and use in decision-making and governance. The utility of different ways of knowing is contingent as much on how the politics of knowledge and expertise (whose knowledge counts) are managed as much as on what they contribute through their content, methods, or theories. Privileging some types of knowledge over others will continue to limit our ability to understand and solve complex problems. From a practical perspective, I propose that capturing the existing configurations, dynamics, and cognitive dimensions of different ways of knowing the city—or how cities think—can help anticipate and assess potential barriers to using different ways of knowing in understanding and managing urban ecosystems.

about the writer

Camilo Ordóñez

Camilo is a research associate at the University of Toronto. His interdisciplinary research is about the social and ecological issues of nature in cities. He works in Canada, Latin America, and Australia.

Camilo Ordoñez

Latin America is the most urbanized region on Earth, demographically speaking. It is of no surprise that the region needs to develop a progressive model for managing its urban ecosystems. Many would argue for such knowledge to be based on previous successes in other parts of the world, by, for example, building massive transport networks and designing new buildings based on the idea of social inclusiveness, as it happened in Bogotá and Medellín, Colombia, in the last 10-20 years. This model of new urban design has been mostly positive and helped transform decrepit buildings and roads into modern, functional, and accessible spaces.

Yet, I can’t help but wonder whether these achievements are mere imitations of what is going on elsewhere or if they conform with Latin America’s own idea of urban ecosystem sustainability. This criticism expresses the notion that rather than using the knowledge we have of urban ecosystem services to influence our interpretation of them, we could, in tandem, cultivate the knowledge of ourselves as a determinant of how we value the urban ecosystem. I always find it hard to articulate this idea. So let me add a bit more to it.

One of the guiding questions behind my research is whether experts can really claim to be in the know of how to manage the urban ecosystem if they have a limited understanding of what it means to urban citizens. My work in the last few years has focused on developing a better understanding of what people value in urban forests, that is, the collection of all the natural and planted trees in an urban area. There is a lot of research out there about urban tree services in terms of cleaning the air, reducing attention deficit and crime, and providing a space for recreation, among many others. In some ways, our idea of the importance of urban forests is mostly based on the physiological reactions people may have when surrounded by urban trees. What I wanted to understand was what kind of things mattered to people about urban forests based on a direct experience with them as a way to express the psychological underpinnings behind their deep connection to this vital element of the urban ecosystem.

Based on my urban forest values research in Colombia I see people associate a diverse range of themes with urban forests, from psychological benefits such as calmness and tranquility, to social issues of inclusion, accessibility, and interaction; the aesthetics of views, sounds, feelings, and smells; and tangible and intangible ideas, such as cleaner air and wildlife habitat, or nature connection and admiration, respectively. One of the implications of this research is that a progressive urban forest management directive is not just about planting more trees to provide more services, but about enhancing people’s natural experience of the urban forest to satisfy their values.

With people’s nature experiences being more and more confined to the city, our knowledge of urban ecosystems is defined not just by our professional knowledge of its services, but the knowledge of the values we hold, as urban citizens, in relation to their them. Professional knowledge becomes even more valuable if it can serve as a vehicle to articulate the desires of urban ecosystem dwellers, helping operationalize their own version of urban ecosystem sustainability from an inclusive and integrative standpoint and reducing value trade-off. This is especially true in Latin America, a region with rapidly transforming urban landscapes, in both its ecological and social dimensions. Bogotá’s initiative to protect its urban wetlands and making them accessible by building cycling routes around them is one of the many examples that could be emulated and even enhanced to bring this idea of enhancing the experience of urban nature instead of just optimizing its services.

about the writer

Philip Silva

Philip's work focuses on informal adult learning and participatory action research in social-ecological systems. He is dedicated to exploring nature in all of its urban expressions.

Phil Silva

This question is predicated on the idea that understanding urban ecosystems is a necessary precondition for managing urban ecosystems. What if this isn’t true? What if we can never completely understand urban ecosystems in a holistic way? Every scholar of urban ecology makes a point of emphasizing the irreducible complexity of these systems. They are “wicked problems” that elude the parsimonious cause-and-effect worldview at the heart of almost any consensus definition of science.

How, then, are we to make sound policy and planning decisions that shape the future of urban nature if we can’t fall back on the knowledge provided by scientific inquiry? Two extreme and opposite viewpoints often present themselves. The first involves barreling ahead as if we actually can acquire concrete and incontrovertible knowledge of the holistic workings of urban ecosystems—despite all the ink we’ve spent arguing otherwise. The second swings wildly in the other direction and has us throwing up our hands in the face of complexity, leaving any planning decision to pure chance. We slide down one of two slippery epistemological slopes; one that ends in false surety and another that ends in know-nothing paralysis.

A philosopher like Nicholas Maxwell might look at the choice between these two extremes and urge us to simply leave these questions of “ways of knowing” and “producing knowledge” aside, striving instead to search for useful wisdom about urban ecosystems. Maxwell argues that traditional knowledge production is not compatible with any concern for usefulness or applicability. The aim of knowledge production is, instead, a gradual increase in our storehouse of tested and immutably proven statements about the way things are. Wisdom, on the other hand, is concerned with figuring out how to make things work in the here-and-now. Wisdom is context-bound and value-laden. Wisdom says, “Maybe—we’ll see what happens” where knowledge says, “Definitely—we can predict what happens.”

Urban planners and policy analysts spent much of the twentieth century looking for immutable knowledge to inform the day-to-day management of cities. It turned out that cities—along with the rest of human society—defied the simplifications wrought from social science, and many a big mistake was made under the cover of “rational” or “empirical” planning. Library shelves are lined with books that bear witness to what happens when silver bullet solutions to complex urban problems only end up making matters worse.

Jane Jacobs, the urban planning critic, built her career on a careful analysis of the unforeseen consequences of applying hard-nosed knowledge to the messy reality of urban life. She called cities problems of “organized complexity” and urged planners to search for useful wisdom in the particulars rather than lean too heavily on one-size-fits-all proclamations of scientific fact. Charles Lindblom, writing for an academic audience shortly before Jacobs published her Death and Life of Great American Cities, made more or less the same argument: rational, scientific planning is all well and good when the whole complex system can be processed and understood. Short of achieving that comprehensive understanding of the whole, we shouldn’t seduce ourselves into believing that our insights are anything but time-bound and contextual, liable to be upended by unforeseen consequences at any future moment.

Scholars of rural environmental management have recently come to similar conclusions about the complex systems they investigate. They write of an “adaptive collaborative management” approach for rural ecosystems that uses incremental a “learn-as-you-go” approach to problem solving for forests, fisheries, and even farms across the globe. Local environmental managers, researchers, community members, and government officials work together in an adaptive co-management process to monitor the outcomes of different management strategies, reflect on what they discover, and adapt their practices from season to season, year to year.

One might argue that the knowledge produced by monitoring the outcomes of different urban environmental management programs is not really knowledge at all. Its chief criterion of validity is usefulness rather than explanatory truth and it makes no claims to applicability across different contexts. A philosopher like Maxwell would likely be more comfortable labeling this sort of insight wisdom rather than knowledge—but for most of us, this is just a matter of splitting hairs. Call it wisdom, call it knowledge, or call it just plain horse sense. The insights that come from taking a step back and assessing what just happened are probably best suited for day-to-day management of complex urban ecosystems. A somewhat stable knowledge of urban ecosystems may result in the process, but let’s be clear—this isn’t the stuff of traditional science. It is knowledge that is good enough for now rather than knowledge meant to last in the form of a universal law.

about the writer

James Steenberg

James Steenberg is an environmental scientist focusing on forest ecology and management. He is currently a Killam Postdoctoral Fellow at Dalhousie University’s School for Resource and Environmental Studies.

James Steenberg

My current work has me reflecting on models—ecosystem models, that is—and their role in understanding nature in the city. From my viewpoint, anytime an environment, or a system, or a concept, is described in anything but its entirety it becomes a model. This could be through narrative, spatial representation, or ecosystem modelling.

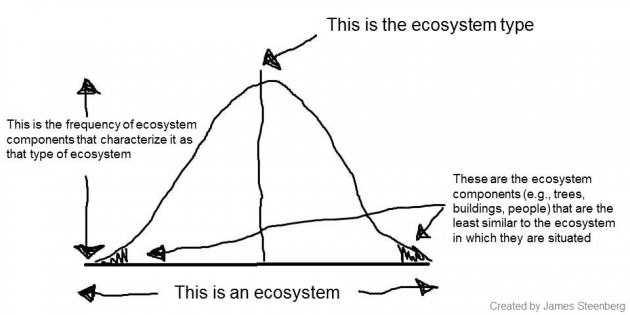

As both researchers and practitioners of and/or in urban ecosystems, we often undertake some form of assumption, abstraction, and aggregation of the real world. We construct a model and therefore omit knowledge. Arguably, the hope is that what has been left behind, whether for the sake of parsimony, practicality, or functionality, does not compromise the model’s utility in describing the ecosystem. This hope is then dependent on what is defined as an ecosystem.

Theoretical discussions on the ecosystem concept no longer view ecosystems as deterministic, stable, or within closed boundaries. They are adaptive, and both scale and context dependent. Importantly, current urban ecological theory now envisions human activities as internal processes that shape ecosystem structure and function, rather than external agents of change and disturbance.

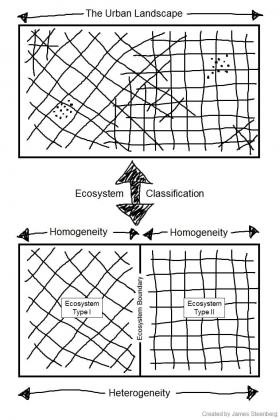

In my own research, I have been attempting to bring this modern urban ecosystem concept from the theoretical to the applied realm. I’m developing a framework for identifying and classifying urban forest ecosystems using quantifiable and spatially explicit variables that represent (i.e., model) their biophysical landscape, built environment, and human population. Ecosystem classification is a form of modelling that attempts to answer the following questions for researchers and practitioners: What does an ecosystem look like? What happened to make it look that way? What will it look like in the future? In such a fashion can they hope to intervene and manage urban ecosystems towards a more desirable state.

However, in the process of ecosystem classification we knowingly ascribe categorical characteristics to continuous phenomena and draw sharp edges around soft boundaries. This latter issue has been long recognized as a caveat of classifying landscapes – as ecosystems or otherwise. Yet, ecosystem classification has still been recognized as a useful tool for modelling and managing complex systems in its hinterland applications where the emphasis is primarily on biophysical ecosystem components.

However, in the process of ecosystem classification we knowingly ascribe categorical characteristics to continuous phenomena and draw sharp edges around soft boundaries. This latter issue has been long recognized as a caveat of classifying landscapes – as ecosystems or otherwise. Yet, ecosystem classification has still been recognized as a useful tool for modelling and managing complex systems in its hinterland applications where the emphasis is primarily on biophysical ecosystem components.

In the urban landscape, where the influence of densely-settled human populations and their social structures and institutions on ecosystem processes are so evident, can ecosystem classification still maintain its utility? Can it be adapted to account for these theoretical advancements in urban ecology and the ecosystem concept?

These are my research questions, though I will admit to feeling apprehensive in shifting from the theoretical to the applied. Specifically, the quantification and classification of the ‘human component’ of urban ecosystems is fraught with challenges. For example, ecosystem classification is, in part, a statistical endeavour. As illustrated above, people at that tail end of that distribution curve who occupy the space outside two standard deviations will be the most dissimilar ecosystem components. In urban forest management, this population may be at risk of marginalization—or perhaps equally likely, may be a disproportionally vocal and influential subset of the population and ecosystem. In the context of building ecosystem models, is the omission of social knowledge as acceptable as that of ecological knowledge?

These are my research questions, though I will admit to feeling apprehensive in shifting from the theoretical to the applied. Specifically, the quantification and classification of the ‘human component’ of urban ecosystems is fraught with challenges. For example, ecosystem classification is, in part, a statistical endeavour. As illustrated above, people at that tail end of that distribution curve who occupy the space outside two standard deviations will be the most dissimilar ecosystem components. In urban forest management, this population may be at risk of marginalization—or perhaps equally likely, may be a disproportionally vocal and influential subset of the population and ecosystem. In the context of building ecosystem models, is the omission of social knowledge as acceptable as that of ecological knowledge?

As a researcher, I’m as fascinated by the flaws of ecosystem classification as I am by the possible applications. I do think that applying ecosystem classification in strategic urban forest planning and management can be a valuable way of knowing and of producing knowledge about these ecosystems. Rather, I think this dialogue is the result of examining social processes from my own physical sciences perspective, and thus emphasizing the absolute necessity of inter- and transdisciplinarity within the research and management of urban ecosystems.

Hi Lindsay

I didn’t see your question until now, but it provoked some thoughts I wanted to share.

I like the idea of seeing elements of the urban landscape as actors. One very good example in my case is the need in Bangalore’s current lake management to determine the boundaries of lakes. This involves both cartographic exercises of revisiting old village maps or getting an official statement from the Department of Revenue (lakes were, as part of the agricultural productive system, an object of value belonging to the State), but also physical raising of bunds or erecting of fences for the protection of the lake or of visitors who might fall into it.

However, the lakes historical functions were not to exist in a constant form or size. Lakes swelled and shrank with the seasonal monsoons, and some years dried completely – which allowed farmers to collect silt for their fields, giving them a nutrient boost while also increasing the lake’s water-holding capacity. Leaving room for these fluctuations also meant that lakes could act as a buffer, and protect against more severe flooding after heavy rains.

Ignoring the internal dynamics of these hydrological entities might seem more efficient in a Bangalore that strives to become a “world-class city”, but if lakes are confined to fixed areas there is a risk that resilience to extreme percipitation is reduced.

As for urban dynamics that may be specific to the South, I think that the urban/rural distiction is often less clear in Bangalore (as well as in East Africa, where I’ve worked before) compared to many Western countries. I’ve seen a higher rate of mobility in Bangalore and other cities that are going to more rapid changes, with people in very different income groups moving into and between cities for jobs. Moving to the city also seems like a less permanent or definite step. Many still own a plot of land in the “home” town or village, many send remittances to their families and/or visit them regularly over the holidays, and never really get rooted in the constantly changing cities.

I’d be very happy to hear Doreen’s thoughts on this – does it sound familiar to you or is your experience different?

I think there are many answers to this month’s question also in last months roundtable on the arts — http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/11/02/how-can-art-in-all-its-forms-exhibits-installations-and-provocations-be-a-better-catalyst-to-raise-awareness-support-and-momentum-for-urban-nature-and-green-spaces/

Yes, trees elicit a different response than a sewer pipe, I would agree! Good point.

In the spirit of this blog that is meant to be provocative, could there be class/gender/race processes that shape individuals’ relationships with those infrastructures? Trees may offer some sort of privacy for homeless, and it that sense, may serve as a both a grey and green infrastructure?

Hi everybody!

I’m wondering if somebody has had the chance to read the article about the rise of the suburb in the developing in The Economist last week. I found the article very interesting. From my own experience in Latin America, I think the discussion about surburbs, as a model of urban development and, in a complementary or reactive manner, also a model of urban ecosystem management, is one that we must have as urban ecosystem managers, or people who tinker with the idea of urban ecosystems. None of us has mentioned suburbia in our postings. I guess it ties a bit with what James was saying about classifying the urban ecosystem landscape, which by the way I think it’s imperative if we are to understand how urban forests evolve, since different urban development models have resulted in different urban landscapes, and in turn, in different ecosystems for the nature that’s there, and different social systems for the people who live there. What I find interesting about the article in The Economist was that many countries are following this urban development model automatically, without even thinking about it, as a consequence of economic and social transitions (i.e. higher salaries, less people in the countryside, industrial developments in the outskirts, smaller, more compact families, etc.). And I wonder about the impact this model will have on cities and the nature within them in the coming decades.

I just wanted to point that out, throw it out, see if anybody reacts.

Thanks a lot for the opportunity and thank you all for your postings. I enjoyed them a lot.

Camilo

Hi Everybody!

Very interesting ideas, thank you for your contributions! I’m sure I’m not doing justice to everybody, but I just want to point out:

Thank you Philip for your comments. I like the way you articulate my own idea, I guess one doesn’t understand his/her own ideas unless they bounce off somebody else, so thank you! Yes, examining the social meaning of urban nature is extremely important if we are to bring the idea of “ecologizing” the city closer to home. At a deeper level, I guess the point of bringing values out to the table is to avoid seeing management as a professional endeavour, where the recipients of knowledge choose its direction, but rather as a collaboration, a conversation. And once that conversation starts, it never ends. Of course professional knowledge is important, but to be better managers we need to be broader thinkers.

Thanks a lot! More comments to follow.

Camilo

Tischa points to the need to pay attention to networks and politics in the creation and management of urban social-ecological systems. I’m interested to hear more about who some of the key nodes and brokers were in the networks she studied.

I completely agree with this statement and have begun to delve into questions of networked governance in my own research on urban sustainability in NYC. As I mentioned in my blog post, I am primarily a qualitative researcher and I believe strongly in the importance of stories and case studies. My doctoral dissertation examined the politics, discourses, and material practices of urban forestry and agriculture in NYC in the time of the city’s sustainability plan, PlaNYC2030. In numerous presentations to scholarly and practitioner audiences, I have shared details of my two comparative case studies, about how more state-led and centralized the forestry sector was and how more civic-led and polycentric the agriculture sector was. Then, I present two social network diagrams offering a visual snapshot of these networks, and often I hear a gasp—as people see, visually, how distinct these two networks look. Presenting the visual display along with the narrative account helps triangulate my data and speak to people who have different modes of learning and understanding.

But network diagrams are just one way of visualizing data. What other techniques have folks used to help tell compelling stories? Particularly for Tischa’s focus on ‘how cities think’, what are some creative ways for visualizing knowledge production?

Both Johan and Doreen are working in growing cities of the Global South with long historical legacies of colonialism, development, and change.

I’m interested in the role of the landscape in both of these cases – how it persists and even resists some of our attempts to re-shape it. The mountains, hills, streams, and lakes are themselves actants in these complex social-ecological systems.

Johan points to the need for grassroots engagement with lakes, so that we can take our cues from people and the landscape more directly, rather than imposing some ‘rational’ (or disempowering, or othering) top-down logic on them.

How else can we recognize these non-human actants? As landscapes inevitably change with development, human migration, and climate change, what difference does it make if we think about the landscape having a memory? And what opportunities does thinking about landscape as actor open up in trying to seek more just, equitable, or sustainable solutions to urban form and planning? Or should our attention remain squarely on human needs, particularly in cities with histories of colonialism or other structural inequalities?

Trees seem quite different from ‘grey’ infrastructure in particular because of their dynamism – they grow and they DIE. As much as we try to focus on tree survival and health, ultimately they are living entities. They also seem to invite more intimate, emotional, and affective relationships than, say, a sewer pipe — see Owain Jones’ chapter in the volume that Adrina recently co-edited “Urban Forests, Trees, and Greenspace: A Political Ecology Perspective.”

Raising the difference between community gardens and parks just puts a finer point on it. Maybe they provide some of the same *regulating* services, but the socio-cultural services are completely different, and that is largely because of the governance structure. People engage with gardens in totally different ways from parks – as stewards and managers of common space. Therefore, they co-produce different sorts of socio-cultural benefits through engaging with these spaces.

I’ve recently started getting more familiar with the “green infrastructure” concept, and it seems like there are some pretty wide ranging thoughts on just what that term means. I think to many, trees would be challenging to preexisting notions of an infrastructure. There are different ideas of what counts as infrastructure. Are trees a means to an end or an end in itself? If we think of them as means only, then perhaps they are substitutable with something else. But since I know you’re a tree person, I’m sure you have some thoughts on what makes them special in their own right. Same with parks vs. community gardens. From an ecosystem service perspective, they might be the same thing–urban green space. But they are thought about in very contrasting ways that have had very different consequences in urban planning (see this paper by Mark Francis, “some different meanings attached to a city park and community gardens”).

Phil is bringing up the tension between two opposing perspectives–try to know everything or just give up–that Lindsay also refers to in the Science Wars.

For me, one promising outlook would be not to frame knowledge as a choice between universal and particular, but to do both (like Lindsay and Tischa point out). I am brought back, though, to my reference to Flyvbjerg (which this conversation got me thinking about after reading his work a few years ago). He proposed a new kind of social science, a “phronetic” science, which he attributes to Aristotle. It is neither a search for universal laws nor a chaotic surrender to particularities, but a practical knowledge: what do certain people do in certain situations? For him, case studies are generalizable, just in a different way. Based in the particular, but useful in other times/places. Maybe the usefulness of “ways of knowing” means to move from “knowing” to the “thinking”–don’t worry too much about what we know but rather about how we think.

Nate Gabriel raises fundamental questions about our assumptions, language, and policies surrounding urban nature (and particularly commons).

In trying to ‘think differently’ about cities and nature, I keep coming back to the notion of resilience. I find myself wanting to step outside the current moment to try to understand the implications of this turn from sustainability to resilience thinking. Of course, like any good situated scientist, I cannot step outside my current historical moment or subject position. But I do find myself yearning for some critical distance and a longer view—which is why I think historical approaches to understanding city form and city politics are so crucial.

Regarding resilience, what is gained and what is lost with this approach? What new silences or practices of marginalization occur? I think that a greater attention to cycles of disturbance and recovery is useful for moving us beyond steady-state or even long-term ways of thinking, particularly in an era of climate change and increased climate variability. But some critics have argued that resilience mentality and planning for disturbance is yet the latest way of foisting responsibility for adaptation onto the least powerful. Julian Agyeman made an important corrective to sustainability thinking when he proposed ‘just sustainabilities’ – what would it look like to have ‘just resiliencies’?

Luke offers a thoughtful examination of different definitions and understandings of vacancy, pointing to the importance of language in shaping our urban ecosystems.

In my own work, I’ve sought to examine the implications of considering trees as “green infrastructure” as we see so often in current city policy and management. With this turn, we argue that natural elements are crucial to the basic functioning of the city. It also comes loaded with the prior understandings about proper roles of state and citizens in creating and engaging with infrastructure. But in seeking civic stewardship of trees, some of these assumptions then have to be questioned and re-worked.

What other implications come from thinking of nature as infrastructure? Further, can we examine the multivalent meanings of terms like sustainability and resilience – what political and material effects can we detect from these varied discursive formations?

Hi Bryce. I’m not sure how to think about your question yet. Everything below is just thinking about loud.

I think that the latter (speaking/thinking anew) allows us to do the former (interpret affordances differently). Reinterpreting resources is superficial if new thinking doesn’t come with it. Participatory management schemes, for example, can provide opportunities to think differently about parks or whatever object of management is in question. But often, I think these schemes end in failure because they often desire fixity, when openness to the underlying assumptions about what is to be managed is a prerequisite for change. They are fundamentally oriented toward conceptual closure rather than openness. They ask, “if not this, than what?” In my view, it’s better to say, “This is alright, but what else?” The best we can do is to keep asking “what else?”, even after we get an answer. From a managerial perspective, I think it’s important to recognize that tidyness, despite all its advantages for management itself, is just a temporary resting spot between periods of messiness.

I don’t know. I’m still thinking.

Hi Johan. I’m not sure there’s anything inherent about cities that makes the politics of commons/environmental management clearer or easier to see. But historically, I do think that cities (at least, the cities whose histories I’m most familiar with) have tended to be places where commons are enclosed more readily than elsewhere. I think this has to do with how we have known (I like to say “apprehended”) the city as a particular kind of object – namely, one that’s driven by capitalist economic activity. I’m working on developing these ideas and giving them more empirical heft (my next post-PhD project), but my initial sense – and my conclusions from my PhD work in Philly – is that it is through the capitalization of urban space during the 19th century (and the continuing reproduction of this knowledge into the 21st) that commons have typically been seen as at best inconsequential for urban growth (as opposed to privately-owned or tightly-controlled urban resources, like land, which is seen as fundamental to capitalist economic development).

To answer your question more directly, I’m not sure the diversity of perspectives or political/ethical commitments in cities makes politics easier to see. Maybe. Certainly a certain kind of politics. Cities have probably always been places that people could go to escape discrimination, etc. So in that sense, a broader range of overt political stances are probably visible. But I’m not sure that makes them less political, just political in different ways. The kind of politics I’m thinking about is more about what goes unspoken, those things that are so deeply entrenched that we don’t even think of them as political and that is more about the nature of knowledge itself, rather than a particular expression of human society. I’m thinking of focus groups I conducted for my PhD, when I would ask people about foraging in parks. Their immediate response was not revulsion or anger, but confusion. The possibility of foraging, for most folks, simply didn’t exist. It’s wasn’t a conscious political stance against foraging. Foraging just fell outside of what they silently thought about parks and cities. In this way, for me, the politics of the issue has less to do with a power structure produced or promoted by a powerful elite than it does with a framework of understanding and living that grips all of us (some of us more than others).

Hi James, I appreciate your comments on the differences between models of the world and the world itself, especially your question about the utility of ecosystem models in an urban context. It seems to me like the question of spatial and temporal scale in these models and their utility – and the relationship between temporality and spatiality – becomes especially important in an urban context.

I think your caveats about the utility of ecosystem modeling suggest that, in the aggregate, ecosystem classification is useful even though we acknowledge that it ignores micro-scale interactions (I hope I haven’t oversimplified your argument). No matter what models we produce of the world, we miss detail. As geographers are so fond of saying, the map is not the territory.

It seems to me that what characterizes urban ecosystems is rapid change that attends human activity. Of course, that doesn’t mean we can’t have models of urban change, too. There are plenty. But (and now I’m finally getting to the point), I’m curious to hear more about your reservations about how well ecosystem modeling can work in cities. Is it because you see human societies as operating on a different time-scale than ecosystems? Are the forces that shape material conditions in cities somehow more dynamic or disruptive than the forces that prevail in non-urban settings? If so, can ecosystem modeling work, given the rapid change that attends urban socio-natural assemblages?

On the point of more knowledge, knowledge as cumulative, etc, I think this question is made clearer if we think about knowledge as situated, partial, etc. Nothing new or groundbreaking there, but I think it does remind us that less knowledge can be better than more knowledge if the knowledge you have is the wrong stuff. The point is that knowledge is active in the world – it shapes what we do. I think Phil’s getting at this with his points about scientific vs management knowledge. So more scientific knowledge, in the absence of managerial knowledge, tends to make management questions into scientific/technical ones. Similarly, to Johan’s question, knowledge about the city as human space, in the absence of knowledge about the city as environmental (or socio-environment) space tends to lead us to questions that ignore the possibility of the latter. I think this is exactly the problem Phil’s pointing to, but is also a clear example of where “more” knowledge is exactly the problem.

For me, this conversation also raises key questions about the relationship between ethical commitments and knowledge. On Johan’s question about the right to argue in favor of particular social arrangements, I would say that this is precisely the what we should be (and are) doing all the time. It is only through argumentation that we are able to clarify our ethical commitments (and the knowledges that attend and are required to support them). To deny the fact that we have ethical commitments reduces our ability to engage in debate about those commitments. It’s only through argumentation that we are able to examine the assumptions that underpin our knowledges of the world, and have an opportunity to produce new/different knowledge.

Sadia picks up on the idea of practical wisdom as well – or knowing through doing.

I see clear links between Sadia and Bryce’s exploration of the affective, embodied experience of tree planting, dune creation, and surfing. In both cases, the embodied experience is the “hook” that leads to further action. Sadia shows that working with plants and dirt is a way in for engaging students in environmental learning. Bryce demonstrates that the experience of surfing triggered surfers to later engage in dune re-creation post-Sandy.

It is exciting to talk about bodies, love, and governance as all connected. So often, even our most participatory approaches to planning and policymaking are dis-embodied and attempt to proceed ‘rationally’. Yet, we often see emotion bubble over – in public hearings, on the floor of legislative bodies, in letters to editors—and bodies re-emerge as visible in protests at City Hall.

We need to acknowledge, accept, and tap into emotions (including anger) as legitimate forms of expression and discourse. Iris Marion Young makes the point that a truly democratic, deliberative, and inclusive society will embrace non-‘rational’ modes of communication as valid and important to dialogue and progress. In the wake of so many racially charged tragedies and social injustices in recent days, followed by protest and civil disobedience—the importance of acknowledging and working with emotion is made all the more salient. Perhaps if we can allow emotion to have more of a place in our everyday governance, we won’t have to wait for tragedy to strike for frank dialogue and citizen engagement to occur.

Thank for everyone’s insightful comments so far!

I appreciate Johan Enqvist’s comment to “learn from learning…to create…approaches for…case-specific wisdom”. Different ways of knowing and approaches to learning are integral for personal and community growth. In my own experiences in urban forestry, stories have proved to be a powerful tool in shaping ways of learning and knowing to help foster critical thinking about broader issues. For example, one project that I was involved in at York University was the Alternative Campus Tour (http://alternativecampustour.info.yorku.ca/) where students were challenged with reimagining common assumptions about their immediate physical environments.

I agree with Doreen and James’ comments that there needs to be better integration between theory and practice. In my own experience working in the field for a number of years and then finding myself in a doctoral program, there was a considerable learning curve. I also noticed the lack of applied integration into the curriculum structure once I started teaching. I strongly agree with James there are many complexities in developing a curriculum for urban ecology and urban forest management systems. In urban forestry this is certainly the case where more attention needs to be given to practitioners, field workers, and arborist perspectives.

I’m particularly interested in the concept of citizen-labourers – much of my research has focused on challenges and under-represented stories of this dual role in a healthy social ecology. Through personal narratives and values, interview participants evidence the depth of knowledge that could be considered to help shape policy and develop more socially inclusive management practices. As such, both theory and application can better inform one another in urban forestry.