Remnants of indigenous vegetation in urban and rural areas often are the only remaining examples of ecosystems that were once more extensive before human settlement. They are therefore vital for preserving and promoting biodiversity. Remnant vegetation also serves as a refuge for indigenous plants, fungi and animals that would not otherwise be found in an urban environment. A major influence on the flora and fauna of natural remnants is the type of surrounding habitat (for example, Doody et al. 2010). In cities, the surrounding matrix is often residential houses and their gardens. These gardens can provide food, shelter and connectivity between green spaces making them an important habitat for some wildlife, including invertebrates. Terrestrial invertebrates are a major component of biodiversity in all ecosystems including urban environments. They are logical choice for studying the effects of urbanisation; they are diverse, have short generation times, are fairly easy to sample, represent a spectrum of trophic levels and are important components of human altered landscapes. They fulfill many important and roles such as decomposers and pollinators therefore are an ideal subject for monitoring biodiversity in urban ecosystems.

And here we begin today’s story…

Christchurch City, New Zealand is an ideal urban environment to explore questions about invertebrates in indigenous remnants, private gardens and also restored native vegetation. And the dispersal or otherwise of invertebrates between different vegetation types. There is a large (c. 8 ha, Riccarton Bush) indigenous forest remnant in the city, thousands of private gardens and also quite a number of areas of native woody vegetation that have been planted over the last 20 years. And, as luck would have it, a scientist (Richard Toft) investigated the invertebrate communities of all 3 vegetation types in 2003. He sampled beetles (Coleoptera), moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera) and fungus gnats (Diptera). So that leads us to the current study.

By re-sampling the sites that Toft sampled in 2003 we can ask the question: if we plant the plants do the insects follow? That is, by planting the plants are we achieving the goals of increasing indigenous biodiversity and restoring fully functioning ecosystems? After 20 years do the planted native vegetation sites contain similar invertebrate assemblages to the remnant forest?

In 2013, one of us (Denise Ford) here at Lincoln University resampled the Toft sites. Using malaise traps (as Toft did in 2003) the 3 groups of invertebrates were sampled at the same sites as in 2003. Six sites in the forest remnant (4 more than Toft), 1 on the edge of the remnant, 7 in private gardens, and 2 in a c. 20 year old area of planted native vegetation (Wigram Detention Basin). We also sampled a few extra sites in 2013 but we won’t report on these here. And so what did we find??

Despite sampling in an urban environment, the invertebrate communities were predominantly native—in 2003, 84% to 16% adventive. Interestingly though, 28% of the native taxa were confined to the forest remnant. Few adventive species were found in the forest remnant. Suburban gardens also contained a surprising number of native taxa, especially Lepidoptera even though adventives dominated in richness and abundance (82%, 70%). In 2003, the planted native forest site (then c. 10 years old) had more taxa in common with private gardens than the forest remnant.

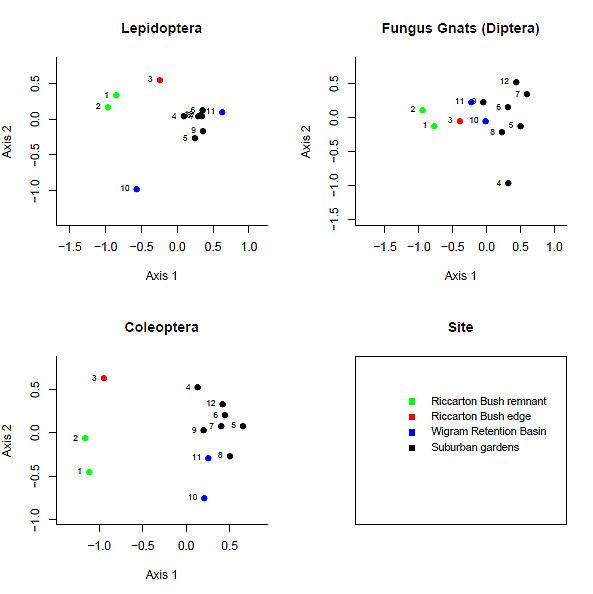

All four sites had distinct species assemblages as indicated by their separation in the ordination, a statistical technique that describes and analyses differences among complex sets of attributes, such as ecological communities (Fig.1). The remnant native forest is clearly different in species composition from the restoration site and private gardens for all 3 insect groups. Interestingly, the forest edge site was intermediate in terms of compositional similarity between the remnant and the other sites. The gardens and restoration sites were similar in composition for all 3 insect groups, as indicated by similar positions on Axis 1 (Fig. 2.). However, Coleoptera were widely spread along axis 2, indicating that Coleoptera composition was not as similar between gardens and restoration sites as Lepidoptera and Fungus Gnats (less spread on Axis 2). So in 2003, the insect composition was quite different between the native forest remnant and edge, and the restoration site and private gardens (which were similar in composition). The former dominated by native species, and the latter by adventive ones.

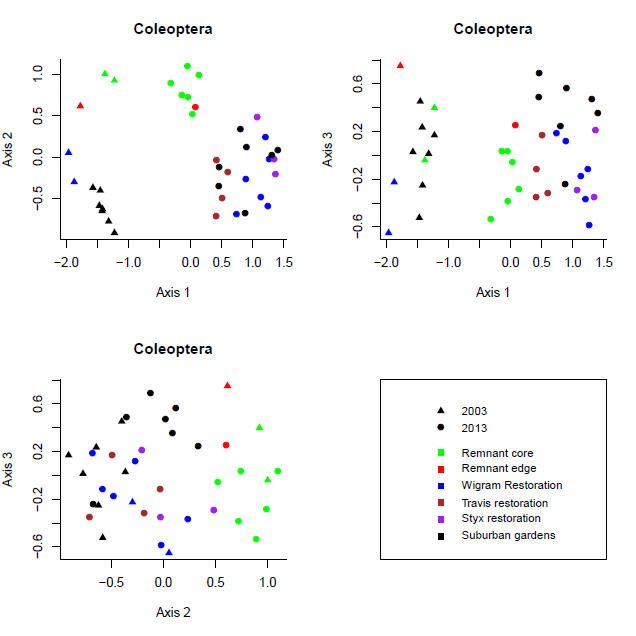

Species compositional differences were apparent between the two surveys. Take Coleoptera as an example. The forest remnant and remnant edge were separated from the other sites on Axis 2 in the ordination (Fig. 3, top left graph; bottom left graph). Interestingly, the composition in the remnant forest and edge had changed over the 10 years, as indicated by a separation on Axis 1 of the ordination (Fig. 3, top left; top right). Similarly the Coleoptera composition of gardens had changed between 2003 and 2013 (Fig. 3, top left; top right; black triangles and black circles).

One might expect that at some stage the planted native forest will begin to contain more of the taxa present in the native forest remnant (3.5 km away). But after 10 year’s (since Tofts study) the remnant was still dominated by native species of insects, and the gardens and restoration site by adventive species. The planted native forest site in 2013 did share a few native insect species exclusively with the forest remnant, however, a greater number of species found in the planted site were also found in gardens (many of which were absent from the remnant). Lepidoptera was the only insect group in the planted site that indicate that species composition was getting more similar to the remnant. Insect composition in the planted sites will be influenced by vegetation structure and the characteristics of the species themselves, proximity to source areas, and their ability to disperse and establish a viable population. Many species might be incapable of dispersion and therefore in need of translocation. Others might just find the garden matrix between the remnant and the restoration sites unfavourable to cross?

One finding of our re-survey was that we collected at lot less species from all sites than in 2003. For Riccarton Bush a substantial decline in the number of the larger Lepidoptera compared to 2003 is of real concern, and was contrary to what we expected. This does not bode well for the maintenance (or perhaps even enhancement?) of invertebrate biodiversity.

The results of the surveys also illustrate the importance of regular sampling to evaluate restoration success towards a fully functioning forest ecosystem and to monitor the health of the restored sites. Although a 10 year interval appears to be too long to show the trends we found. Hence we cannot say much about the implications for ecosystem function.

Our re-survey indicates that it may take many decades yet for the planted patches of native forest to contain invertebrate taxa in common with the native forest remnant. So, in answer to our original question—if we plant the plants will the insects follow?—indications after 20 years are positive but it maybe too early to tell just yet.

Denise Ford

Glenn Stewart

Christchurch

Doody, B, Sullivan, J, Meurk, C., Stewart, G. & H. Perkins. 2010. Urban realities: the contribution of residential gardens to the conservation of urban forest remnants. Biodiversity and Conservation 19: 1385-1400

about the writer

Glenn Stewart

Glenn Stewart is Professor of Urban Ecology, Lincoln University, NZ. Current research is on Southern Hemisphere urban ecosystems and invasive species, successional processes and predicted changes in global climate.

That is very nice to I think those problems you refer to, however, may be due to it being branded as "history of there should also be straight philosophy where kids are taught how to problem solve and create good reasoned arguments for their beliefs, not just memorizing when who said

Hi Andre

Yes you are right, the reduction could well be from environmental factors. I think the results show a need for regular monitoring. In 2006 a predator proof fence was erected around Riccarton Bush and mammalian pests such as rats and mice were eradicated. One of my hypotheses was that the number of larger bodied invertebrate species would increase because of the reduction in predation. For Lepidoptera was not the case (I only looked at this group) in fact the opposite was the case. This certainly needs more investigation using a greater number of species.

Hi Di

I didn’t come across anything for constructed wetlands habitats in Canterbury. There does seem to be a lack of monitoring for terrestrial inverts. Regards Denise

Many thanks for that monitoring & write up. Is there data on invertebrate take up for constructed wetland habitats around Christchurch / plains?

Thanks for the inyteresting article – I think TNoC would benefit from more empirical studies like this. How incredible, also, to have 450-year-old trees in the middle of suburbia! One question: how sure are you that a reduction in species found in the more recent sample (compared with 2003) is indicative of a worrying reduction in actual biodiversity? Might there be environmental factors causing a temporary lull; or a mis-match of sampling technique? As you say, further samples are important and I think part of that importance is due to the need to smoothe over such potential influenbces.