Forget the damned motor car and build cities for lovers and friends.

—Lewis Mumford, My Works and Days (1979)

Humanity managed for the better part of 400,000 years without cars and did just fine. Julius Caesar, Michelangelo, William Shakespeare, Adam Smith, and Abraham Lincoln lived in cities and never drove an automobile. They didn’t need one, or thought to need one. And you wouldn’t need one either if we could arrange our lives such that you can get where you need to go without a car.

What does this have to do with the nature of cities? Cars are Enemy #1 for the nature of cities. Not only do gas-propelled vehicles pollute the environment and contribute to climate change, the roads they require take up space, robbing room from us and from nature at large.

What does this have to do with the nature of cities? Cars are Enemy #1 for the nature of cities. Not only do gas-propelled vehicles pollute the environment and contribute to climate change, the roads they require take up space, robbing room from us and from nature at large.

Standing on a sidewalk, a person occupies about four square feet (0.4m2) of land; most cars take up 80 square feet (7.4m2), twenty times more, and that’s before they start moving. In the United States suburban zoning regulations commonly require three parking spaces for every 1,000 square feet (92.9m2) of office space.

Because a standard parking space measures 330 square feet (31m2), this regulation means that a one-story building requires as much asphalt as floor space; a three story building requires paving the soil at a rate of three times the footprint of the office itself!

So, as a result of car dependence, most cities blithely commit 30% percent or more of their valuable urban space not to people or nature, but to cars, counted in millions of square feet (or meters) of streets, parking spaces, garages, and parking lots.

Think how absurd it is that skyscrapers, a thousand feet high, can be found going toe-to-toe with parking lots covered in a single layer of cars, yet downtown parking persists in the midst of the most valuable real estate in the world.

Why do we put up with that?

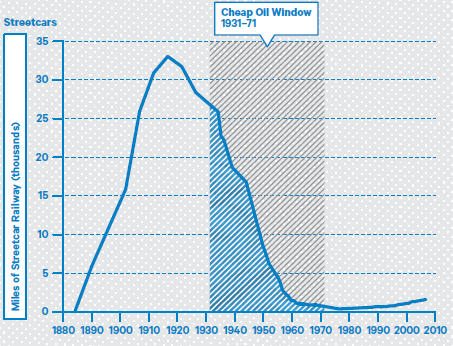

There are three reasons. One, once upon a time, we thought it was good idea to rip out public transportation and replace it with private ways of getting around. In the United States that time was the early twentieth century, when gas was remarkably cheap (on the order of 5 cents per gallon, cheaper than water in some places, cheaper even than oil is today with the fracking revolution) and streetcars were failing because of bad deals struck by government and industry, setting in motion patterns of disinvestment and disrepair. What America discovered with the car was a new way to make a buck, by paving over farmland near town for suburban development, a process now being replicated globally.

Reason two we suffer the car is millions of people depend on their own vehicles to get into town from their houses in the suburbs. These folks value the livability of their homes more than the livability of other peoples’ homes, so demand, through their dollars and their voting patterns and their incessant traffic, that society provide conduits and parking places for their steel boxes. Other people make money off of those people by selling us motor insurance, car loans, gasoline, tires, mechanical services, road paving services, ticket-writing services, and the wheeled boxes themselves. Governments recoup costs through registration and excise taxes. One would be enraged at such uncivil behavior, except “those people” and “those other people” are the same: us! We are all caught in the same self-perpetuating economic loop-de-loop of oil, cars, and suburbs.

Reason three we don’t change is that we have already invested so much into the roadways and the regulations and industries to support this car-mad way of life that change feels, smells, and sounds unthinkable, even if for the millions of people stuck in traffic, consciously or unconsciously, they can think of nothing else. In America, inertia reigns over the Republic. What galls, of course, is that so many other cities, in other countries around the world, are making exactly the same mistake America did and giving over lovely towns and cities and countrysides to automobiles…and their attendant problems.

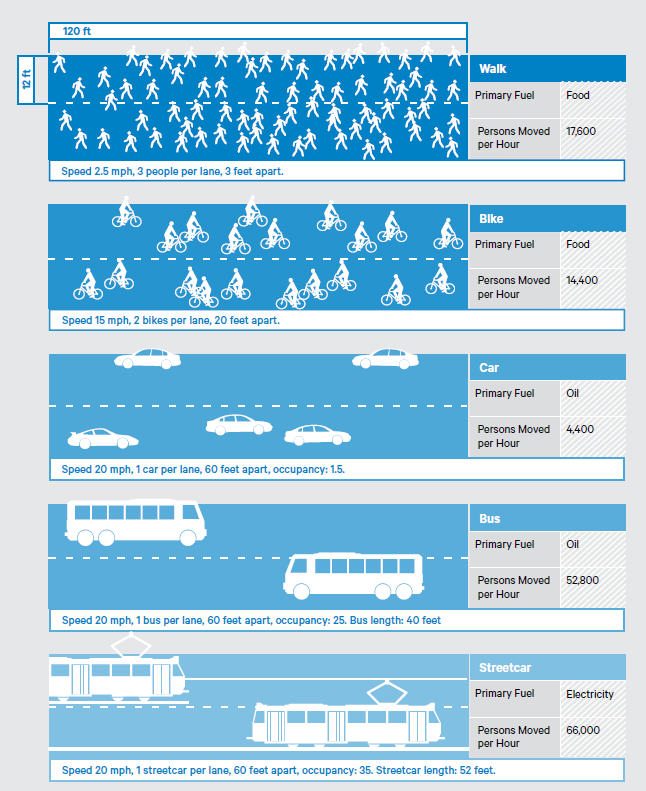

Not everyone needs a car in the city, but all us who love cities must take cars into account. For the passerby, the pedestrian, the person walking in the nature of cities, cars steal our freedom. Crosswalks force walkers to the ends of the streets to wait for a system of authoritarian, automated lights, obsequious servants of motor traffic. Walkers, bicycles, scooters, buses, and streetcars compete with private cars for transport space, while cars are provided an unfair advantage by law (and size and speed). In America, cars on a country road are often represented (especially in automobile advertisements) as the perfect manifestation of freedom, but in cities they destroy liberty for people and nature living downtown.

Journey to work

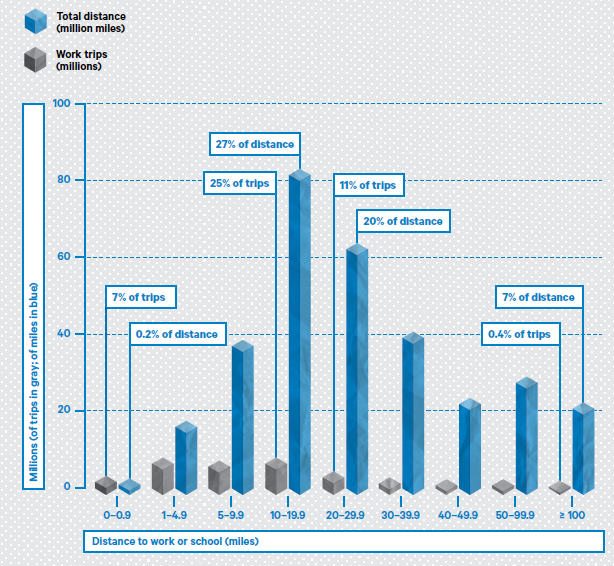

If we want to forget the damned motorcar, we need cities with more than just lovers and friends, as Mumford says; we also need cities with work close to home. No one drives in the city because they want to; they drive because they feel like they have to. Of all the journeys we make, the journey to work is the center of the transportation lives for most people, and choice of transport is the grease that facilitates compromise among the competing demands of family, job, school, shopping and the cost of real estate. Shorter commutes mean better lives for all.

Less driving to work trips contributes toward another important societal imperative: less consumption of energy, particularly transport fuels based on oil and other fossil fuels, that can be used more productively in so many other ways and whose combustion contributes to climate change. Shorter trips help out because a vehicle, any vehicle, uses less energy over shorter distances. That’s physics. Most working Americans make 500+ journeys between the workplace and home per year. The commuting multiplier means that even small reductions in the distance from home to work subtract considerably to total distance travelled, and therefore the amount of fuel consumed.

Trip distance is also an important determinant of how people choose to transport themselves. Travel is constrained by available time as well as required distance, and different forms of transportation move at potentially different speeds. Remarkably even in today’s auto-dominated America, for distances less than a mile, forty percent of trips to work are taken by walking (people mostly drive, even for short distances which is remarkable in itself). Biking bumps up to its highest frequencies at distances between one and five miles. Buses, trains, streetcars, and other public forms of transportation, all minority travel modes in most of America, work nicely for distances of 1–10 miles.

Some research shows that people actually enjoy the trip to work, using it to separate mentally as well as physically from the office or factory; one study found a preferred commute time of about twenty minutes. In twenty minutes of walking a person will travel about a mile; twenty minutes of biking can get you three miles; twenty minutes in traffic depends on how heavy the traffic is. In terms of city design, we can think about the “practical commuting horizon”: the distance a person can travel in twenty minutes.

Can we design cities where for most citizens their daily needs (work, home, shopping, school, religion) can be encompassed within a 20 minute walk? If it sounds impractical, then remember for most of human history that was exactly how cities were made. For all pre-automobile settlements, short travel distance was the most important design objective.

Alas! We live in another time. We are more familiar with the implications of getting into the car in the morning to go to work. Observe that once a person decides to drive, then most of the rest of the day’s travel will also likely proceed by car; it make sense to chain our trips together, avoiding the costs in time and hassle of changing from one transport mode to another. Thus the office and the shopping mall and all the roads in-between need to be paved over to make the convenient trip possible, taking that land from nature. Because automobility entails such large upfront investment (car payments, registration, insurance, maintenance, etc.) it also makes economic sense, once you’ve decided to have a car, to use it as much as possible. You are financially locked in to the car, a fact that many people miss when they only consider the price at the pump.

In short, for people in most cities in the United States (and, increasingly, in many cities elsewhere), cars seem like the only way. The logic goes like this. I can’t to afford to live in the city or I want better schools or I want a garden of my own or just I want to be closer to nature or it’s the American Dream…so I have to move to the suburbs. Now that I live in the suburbs, in residential neighborhoods separated from work, shopping, etc. I have to have a car, maybe two or three. And because we all have to have cars, we all have to kill nature to facilitate them.

I call it the Siren Song. Oil, cars, suburbs sing to us this terrible song, that sounds so beautiful individually that it’s collectively calling us to disaster. It’s taken me many years to realize though that the solution is not anti-city, it is anti-bad-city. Cities do not have to exclude nature or be noisy, crowded, and annoying; they have just become that way because of how we have constructed them over the last 100 years, in service to the automobile. Cities can deliver the goods when it comes to an excellent place to live, with jobs and opportunity, and nature close to home. But that means creating cities that work for people and nature, which means taking back some space from the car.

Some gentle encouragement

Better cities begin by giving some gentle encouragement to how we restructure the journey to work. That must be followed by changes in the city fabric, new investments and new alignments of space and capital, and that too requires some encouragement. In all it is a forbidding task to begin imagining 21st century carfree cities. What’s odd—and exciting—about this imagining though is how it makes radical notions suddenly seem normal, even desirable, from the perspective of the nature of cities.

Ecological use fees: Here is radical notion: let’s value the land as nature not just space. What if property taxes were based not only on the economic value of the land and its structures, but on the ecological values of the land itself. In my book Terra Nova, from which this piece has been extracted, I describe a system of ecological use fees as a replacement for the property tax. Building on land takes nature away from all of us; our taxes could and should reflect that. My house means that a forest can no longer grow there. The street in front of my house interferes with the stream that once crossed nearby. We can reflect the ways that development takes public goods inherent in nature and entails them for private benefit. A land tax has many benefits, not the least of which it encourages both efficient development and more open space.

Similar kinds of taxes could be extended to natural resources and pollution in exchange for alleviating less efficient (from an ecological perspective) taxes like the sales tax or the income tax. This kind of tax reform draws on ideas about externality taxes based on the ideas of Albert Pigou and the land value tax that Henry George put forward to much acclaim over a hundred years ago.

Parking Rules: If you are not willing to that far, then changing zoning and parking codes can go a long way on their own. Simpler, clearer, zoning codes that value nature can be explicit agents of densification, rather than anti-densification. We need to reduce parking, or at least make people pay a market price for it. Parking is a critical lever because without parking a car is like an albatross around the neck (i.e. a terrible curse) once you’ve arrived at your destination. In the United States, parking regulation is almost entirely the province of municipal government. Any city could ban parking if it wanted to or at least set a fair price that includes all the costs imposed by cars in town.

Zoning Codes: Taxes, zoning and regulation should also encourage, not discourage, mixed uses of work, residence, and shopping, so that a person can go to work in the neighborhood and shop for necessities on the way home while on foot. A few more people closer together in neighborhoods with a combination of retail opportunities, employment, and residences mean that a person can trip chain to get the groceries and pick-up the kids, and still get home at a reasonable hour by walking, biking, or riding the street car. And you may find that you like your neighborhood better by experiencing it at lower speed; you will see more.

The average American suburb has between 1,000–4,000 residents per square mile (386–1544 persons/km2). If that density were closer to 5,000 person per square mile, with half the land reserved for open space and nature (Nature Needs Half, anyone?), then most towns and cities could be places with work near home and less need for the car. Note for comparison that Manhattan tops the U.S.A. at 65,000 people per square mile, so in no way does the idea of car-free city mean that every city has to be Manhattan—car-free, human friendly designs work at much lower densities. A couple of apartment buildings and a commitment to streetcars, for example, could do the trick for a lot of current suburban developments.

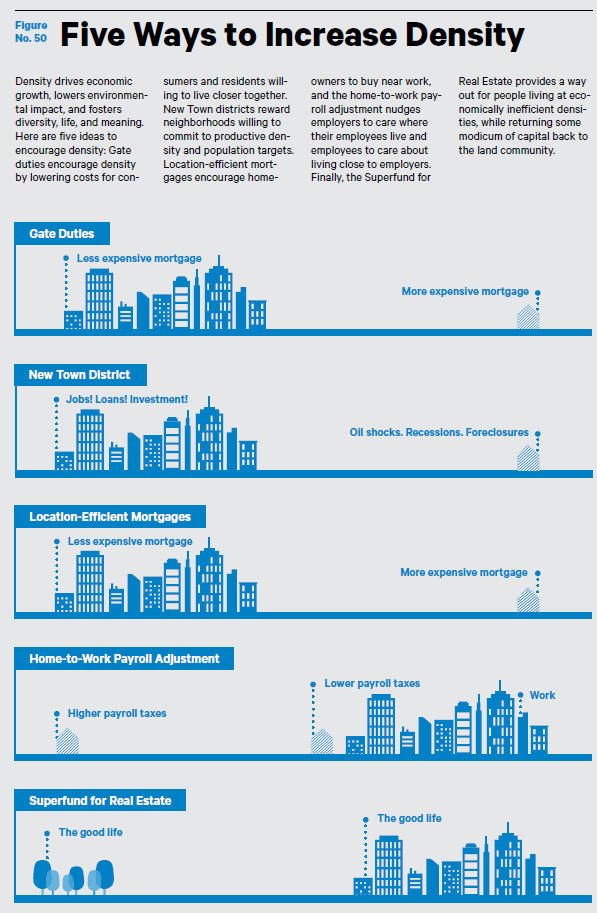

Home-to-work payroll adjustment: A more aggressive suggestion is to use what Google already knows. Every year, each of us reports to the internal revenue service our home addresses and our employer’s address. Google knows the distance between them. We could set up a fee and rebate fund where employers and employees both get a rebate on their payroll taxes when they are close to each other. For example, if a company has a worker who lives within 5 miles, then both the employer and the employee would get a check rebate of, for example, 10%, of their payroll taxes for the year. And where would the money come from? From new fees levied on those who live more than 10 miles from work and his or her employer, with a scale sliding upwards the farther a person lives from his or her designated workplace. Second homes could work into the calculation as well, with a separate assessment made for each additional home. Call it the home-to-work payroll adjustment.

***

Terra Nova describes other ideas too. Location-efficient mortgages that build distance into the calculus for home loans. New town districts that are a kind of business improvement district designed to reward density and autophobic development. A Superfund for Real Estate would help bail out people that invested in sprawl but can no longer pay the taxes. In return for helping the land revert to nature, they would receive a cash payment based on a miniscule tax on capital gains, thus converting monetary capital into natural capital in a real and profound way.

Such measures would send strong signals, via the pocketbook, to everyone that the time has come for a change. The policies needn’t be rushed into existence; the “Nature Yes! / Cars Not So Good” campaign could be introduced with an advertising with persuasive men and women drawn from the cast lists of the car commercials explaining to us all the benefits that pertain; the programs could be phased in over a three or five year period, allowing folks to adapt and to take into account what is coming. Such a program need not last forever either—twenty or thirty years should be sufficient incentive that society reorganizes land use, as it did in the cheap oil window that prevailed in the mid-twentieth century, to take advantage of new incentives. From then on momentum and legacy effects will continue the good work of rescuing urban nature from the highway hydra.

The usual radical

If you’ve read this far, you may be astonished that something that seems as innocuous and wonderful as nature in cities could drive an agenda as radical and heretical as the notion of car-free cities. Beyond a few blessed pedestrian plazas and a handful of auto-less islands in cities, no one since the invention of the cars in the late 19th century has lived in a city without them. Moreover huge industries are invested in keeping us driving in town. Nor can I testify to you as a car-free martyr. My family has a car, we drive to work and school, and given the choices available to us…even in New York City, which has the most extensive public transportation system in all the United States…driving is the best of the bad choices available to us. We are just one among the 44% of New York City households that own cars. (It is an electric car, if that wins us any credit.)

To imagine what a car free experience of the city is like, we need the testimony of people who once lived without a car. Would Michalangelo have had a different relationship to the world’s beauty if he viewed it from a car window? Would Abraham Lincoln had different feeling about his fellow man if he knew them from only from his Presidential chauffeur? John Burroughs, an early-twentieth-century naturalist who lived in New York State was a good friend of Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone. In the 1910s, Ford sent his friend a Model-T as a present and Burroughs wrote back:

I see what a fraud the car is—how much it has cheated me out of. On foot and lighthearted, you are right down amid things. How familiar and congenial the ground is, the trees, the weeds, the road, the cattle look! The car puts me in false relations to all these things. I am puffed up. I am a traveler. I am in sympathy with nothing but me; but on foot I am part of the country, and I get it into my blood. If it were not for Mrs. Burroughs I should hang up the car.

What we need to do to improve nature in cities—and the nature of cities—is convince all the Mrs. Burroughs of the world, all our friends and lovers, to hang up the car, or at least to save it for special travel outside of the city, not within it.

I like to dream of cities without cars, where most people get around mostly by walking, biking, and electrified transport modes, like streetcars and light rail trains that can also be adapted for moving freight. Remarkably the technology already exists, we have prototype situations in cities around the world, and certainly the urgency to build better living places exists in the current age of urbanization. I for one wouldn’t mind skipping the next war over oil, or passing on paving over more forests and wetlands, or not contributing my portion to altering the world climate.

But what I really dream of are cities of nature and a quiet walk by a stream in the Bronx.

Eric W. Sanderson

The Bronx

Extracted and modified from “Terra Nova: A New World Oil, Cars and Suburbs (Abrams, 2013)”

Leave a Reply